Research Article: 2017 Vol: 21 Issue: 3

An Investigation of the Disclosure of Corporate Social Responsibility in UK Islamic Banks

Amr El-belihy, Chartered Global management Accountant

Keywords

Islamic Banking, Islamic Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure (Icsrd), UK Islamic Banks, Content Analysis.

Introduction

Prior Research: ‘Mind the Gap’

Overall social reporting is still at its “infancy” (Abul Hassan and Harahap, 2010), especially from an Islamic perspective (Haniffa and Hudaib, 2010; Napier, 2009). Despite this, literature found that firms from developed countries generally have better disclosure practices than those from developing countries, although developed countries are still facing some issues (Abul Hassan and Harahap, 2010, p. 205). In the current years many contemporary discussions of corporate social responsibility (CSR) have largely been based on a Western direction (Di Bella & Al-Fayoumi, 2016).

It has been noted that Islamic accounting has been criticised for excessively focusing on normative perspectives (Farook and Lanis, 2007; Kamla 2009; Napier, 2009). Also, being obsessed with the “mechanics and forms” of Islamic financial instruments rather than to contributing in benefiting the society; it’s role (Kamla, 2009, p. 921).

Despite this lack of research on social disclosure practice, modest research can be found that is more conscious with Islam’s societal objective. Generally, studies that have highlighted how disclosure levels were practiced by Islamic banks have been minimal (Napier, 2009).

Maali et al. (2006) were one of the few to first develop a benchmark of what Islamic banks should be disclosing whether they are to reflect the expectations of Islamic values. Using content analysis, they compared actual disclosure against their developed benchmark, on 29 Islamic banks that based mainly in the Middle East. They found that social reporting by those Islamic banks was significantly lower than expected. Also, in the Islamic countries in Asia has been discussed in different literatures such as Wan Jusoh & Ibrahim (2017) in their study discussed the Corporate Social Responsibility of Islamic Banks in Malaysia in 16 Islamic banks in Malaysia. This study was an attempt to disclose arising issues on CSR applications of Islamic banks in Malaysia such as all Islamic banks in Malaysia are aware of the importance of CSR. However, the majority of them have not properly disclosed it in their annual reports. Also, the absence of independent CSR division in an Islamic bank implies the absence of autonomy for the bank to conduct its CSR programmes. Additionally, all Islamic banks should establish CSR fund to ensure the continuity of their charitable activities. It seems that without some form of regulatory intervention, reliance on voluntary action alone is unlikely to result in efficient and effective CSR applications. Thus, a special CSR framework for Islamic banks in Malaysia would be a practical suggestion to resolve the issues by including them in that framework (Wan & Ibrahim, 2017).

Similarly, Haniffa and Hudaib (2007) developed an “ideal” benchmark of Islamic values which was “more extensive” (Napier, 2009, p. 128) than that of Maali et al. (2006). The study examined 7 Islamic banks; all from the Arab Gulf countries. Comparing the “ideal” versus “communicated” level of disclosure, they found there was significant “disparity” but mainly minimal disclosure was “communicated” when compared to the “ideal” level. They assumed this was due to the secretive nature in that region and the unconcern of the stakeholders.

Using Haniffa and Hudaib (2007) benchmark; Abul Hassan and Harahap (2010) also used content analysis on Islamic banks from Islamic countries to measure their level of disclosure. They confirmed the status quo that Islamic banks made little levels of disclosure.

Aribi and Gao (2010) wanted to assess the effect of Islam on CSR disclosure on Islamic financial institutions (IFIs). They did this by comparing content analysis of 21 IFIs, versus 21 conventional banks; all in the Arab gulf. It was found that the IFIs made minimal disclosure, although it was relatively higher than conventional banks. This was due to the IFIs disclosing on religious areas such as ‘Zakah’ and SSB.

UK Focus: ‘Filling that Gap’

In summary, social reporting has primarily been based on conventional social reporting systems. Moreover, the few studies that focus on social reporting by Islamic banking have focused on the Arabian Gulf or other Muslim countries without focusing on Western Islamic banks, let alone in the UK.

This is puzzling since the UK is seen as the hub of Islamic banking outside the Muslim world as previously mentioned in the Introduction. Hence the objective of this study is to shed light on disclosure practices by UK Islamic banks, to assess whether the current trend (status quo) of poor disclosure by Islamic banks in Muslim countries is found in Islamic banks due to western environment as the reporting is assumed relatively higher than in developing countries.

Fuelled by corporate scandals and crises such as: Enron, WorldCom and the recent financial crisis, interests in Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) can be traced back to the 1970s (Wood, 1999; Carroll, 1979). Literature has debated mainly on two fronts; why firms might be socially responsible and to what extent do these responsibilities hold (Crane and Matten, 2010), although CSR has become enshrined to various other business and finance debates.

Firstly, CSR is the framing of business ethics, which means addressing what is morally right and wrong in a business context (Crane and Matten, 2010). Despite its continued theorising, CSR can be defined as a firm being accountable for managing its activities, such as in a manner which acknowledges the society and the environment in which it operates. CSR has taken the driving seat at various institutional levels. In 2000, the UK appointed a minister for CSR (Douglas et al., 2004), while the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW) were encouraged to social reporting through various guidelines, as well as entrenching ethics in its flagship professional chartered accountancy qualification.

The launch of Egypt’s MitGhamr Savings Bank in 1963 marked the birth of Islamic banking (Robbins, 2010). Since then, the industry has expanded to over 500 Islamic financial institutions with assets anywhere between $700bn and $1000bn (1-2% of global assets) and 15% growth per year since the 1990’s (Abul Hassan and Harahap, 2010). The UK has become the hub for Islamic banking in the West (Wilson, 2000) and became third in the world after the Middle East and Malaysia (FT, 2009).

Overall, the few studies that focused on social reporting by Islamic banks, have all focused on the Arabian Gulf or other Muslim countries; where poor CSR disclosure has been inarguably the consensus or status quo (Abul Hassan and Harahap, 2010). This means that there were no studies focused on any western Islamic banks, let alone the UK.

The objective of this study is to assess whether the current situation of poor CSR disclosure was found among Islamic banks from Muslim countries in the UK or not. Using content analysis, the study measures the extent of social disclosure of four UK Islamic banks among 2007-2009, using a benchmark of expected disclosures. These disclosures were developed by Haniffa and Hudaib (2007).

The paper has been divided into 6 sections as follows; section 2 presents the literature review, where the basis of the Islamic viewpoint on ethics is introduced. Therefore, building the foundation for reviewing the tenets of Islamic banking, also the detachment from these tenets found in practice. Ultimately, this foundation will also enable a review of Islamic Corporate Responsibility Disclosure. Afterwards, section 3 will introduce the Haniffa and Hudaib (2007) index of disclosure used for this study. Section 4 discusses the content analysis methodology, among other methodological issues. Section 5 will present and critically evaluate the results. Finally, section 6 concludes the key findings and presents the implications for managers, standard setters and future research.

Literature Review

In spite of the limitations inherent in CSR theories, literature has discussed the “Relevance of Religious Ethical Principles to Business Decision Making” (Rice, 1999, p. 345). This includes common grounds between religions (Rizk, 2008, p. 247). An example of this is through the ‘Golden Rule’: ‘Treat others as you want to be treated yourself’” (Bramer et al., cited in Crane & Matten, 2010, p. 106). This rule is also applied to in Islam; in the Quran: “Serve God and join not any partners with Him; and do good-to parents, kinsfolk, orphans, those in need, neighbours who are near, neighbours who are strangers, the companion by your side, the wayfarer (ye meet) and what your right hands possess [the slave]: For God loveth not the arrogant, the vainglorious” (Quran 4:36). In fact the Quran goes beyond saying the Golden Rule by stating in more than four places that “Return evil with Kindness” (Quran 13:22, 23:96, 41:34, 28:54, 42:40). Also, in Hadith, Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) said: “None of you have faith until you love for your neighbour what you love for yourself” (Sahih Muslim), also, “Whoever wishes to be delivered from the fire and to enter Paradise” should treat the people as he wishes to be treated (Sahih Muslim).

The Islamic Viewpoint

Islam is based on Sharia Law; which is found primarily on the Quran (“the book revealed to Prophet Muhammad from God in the seventh century,” Rice, 1999, p. 346). Moreover, the ‘Sharia’ Law is also based on the Sunnah and the Hadith; which are the behavior and sayings of Prophet Muhammad. Secondary sources of Islam include; Ijma (scholar’s consensus) and Qiyas (analogy) (Rizk, 2008). The Quran is taken as the principal guidance for Muslims, while the Sunnah and is an additional form of God’s revelations. Both sources are “presumed to be valid for all times and places” (Beekun and Badawi, 2005, p. 133). The secondary sources do not add anything new and most importantly they must not contradict, overturn or change the Quran. In fact they are complementary to the primary sources, as they elaborate (but not modify) the rules in which Muslims have to follow in order to overcome certain situations.

In order to consider the Islamic perspective credibly, this study relied exclusively on these four sources, as does the majority of literature on Islam. A strong argument in literature is that ethics is preserved into the Sharia Law. Rizk (2008) notes how ethics is “anchored” into the Sharia Law; with ethical values being paramount. The Arabic word for ethics, Khuluq, is extensively used in the Quran (Rizk, 2008; Beekun, 1997). The Quran says; “The word of the lord does find its fulfilment in truth and in justice” (Quran 6:115). This means that the Prophet’s message to mankind was a moral one. Likewise this makes Islam’s focus on business ethics effective because after all, Prophet Muhammad himself was a trader; nicknamed al-sadiq al amen (the honest and trustworthy) for his exemplary ethics (Rizk, 2008).

Additionally, Literature also made it clear that the Sharia Law is set with the objective of achieving maslaha which means social good (Zaroug 1999; Dusuki and Abdullah, 2007). The goals of Islam are the principles found upon “...human wellbeing and good life which stress brotherhood/sisterhood, socioeconomic justice and require a balanced satisfaction of both the material and spiritual needs of all humans” (Rice, 1999, p. 346; expressing Chapra, 1992). Also, Maali et al. (2006) highlighted brotherhood as the root of social responsibility.

“Framework of Social Relations” - The Islamic Perspective

Like any form of social disclosure, Islamic social disclosure is facilitated within a “framework of social relations” (Maali et al., 2006, p. 271), concepts of; Tawhid (unity), ‘Adl&Qist (Justice, Equity and Equilibrium, benevolence and excellence) and Khalifah (Accountability, Trusteeship and social responsibility). The further topics discussed will introduce and facilitate the introduction of the tenets of Islamic banking, Islamic social reporting and finally the Haniffa and Hudaib (2007); the benchmark used for this study.

Unity

The ‘Tawhid’ (unity) concept in Islam, states that God is the creator of all things; where everything acts as one unit and have a sole aim of seeking God’s will (Maali et al., 2006, p. 271). Muslims believe that if they follow God’s commands and the Sharia Law, then he will grant them ‘falah’. ‘Falah’ means ultimate happiness or in other words “eternal bliss” both in this world and in the hereafter (Endress, 1988 cited in Rizk, 2008, p. 250). Through the Tawhid (unity) paradigm, the relationship “between man and God, man and man, man and the environment” is determined (Alhabshi, 1993, cited in Abuznaid, 2009, p. 280).

Islam is perceived by Muslims as more than just an “ascetic” religion (Rice, 1999); instead it requires Muslims to apply the unity concept to all aspects of life. Rizk (2008, p. 252) describes Islam as more than just “a faith: It is an indivisible unit”, which addresses economics, politics, religion and social affairs (Rizk, 2004).

Justice, Balance and Equilibrium

‘Adl’ in Islam touches various principles such as justice, equity and equilibrium (Beekun, 1997). The Quran directly addresses the issue of justice in the quote “Be just for justice is nearest to piety” (Qur'an, 5:8, cited in Beekun and Badawi, 2005, p. 134). Beekun (1997) explains how balance or equilibrium are not the only features of nature and the universe but there are others such as “dynamic characteristic”. This characteristic is what Muslims must pursue in all aspects of their life. Rice (2009) notes that Prophet Muhammad stressed that Muslims should take moderate and proportional positions in all aspects of their life.

Justice is also illustrated in the Quran as ‘qist’ meaning that one should approach things proportionally (Beekun and Badawi, 2005). As it is written in the Quran “...give just measure and weight, nor withhold from the people the things that are their due” (Quran 11: 85, cited in Rice 1999, p. 351). This shows that justice overall is the common denominator to the ‘Sharia’ Law and rules (Ahmad, 1995 cited in Maali et al., 2006).

Benevolence or Excellence

‘Ihsan’ is used in the Quran as it means benevolence or excellence. Beekun and Badawi (2005) indicate that benevolence is similar to kindness. Benevolence was encouraged by the Prophet as he said that kind-hearted people were one of three to enter paradise (Beekun, 1997, p. 28). In a more economic context, ‘Ihsan’ is seen as adding value to the other party without expecting anything in return (Ghazanfar and Islahi, 1997, p. 22).

Ownership, Trustee, Vicegerent and Accountability

Muslims believe God is the ultimate owner of all things, “...to God belongs all that is in the heaven and on earth...” (Quran 3:129 cited in Rice, 1999). Therefore they regard themselves as God’s ‘khalifas’ (vicegerents or trustees) on earth. Vicegerency is understood in the light of trust and responsibility, which are themselves “inseparably linked” (Dusuki, 2008a, p. 16). Although Islam appreciates the right to private and public ownership, this ownership is not absolute. Instead they have been entrusted or loaned to the individual, seeing as God is the ultimate owner (Beekun and Badawi, 2005). Therefore, rather than just perceiving it as an end itself, Islam perceives economic activity as a means (or a trust) to fulfil an end; an end which realises and prioritises social justice (Rice, 1999).

Tenets of Islamic Banking

Objectives of Islamic Banking Comparing with the Conventional Banking

Similar to individuals, the objectives of Islamic banks is to “enjoin right and forbid wrong” (Farook, 2007, p. 35). Islam cannot be divorced from any aspect of life (Walsh, 2007, p. 755) as it is based on the ‘Tawhid’ (unity) concept. Consequently, Islamic banks are expected to have social responsibility, preserved in their operations. Farook (2007) outlines two religious and financial reasons for this:

1. Religiously: The Islamic banks fulfil a “collective religious obligation” (fardkifayah) (p. 32). So, in other words providing Muslims with ‘Sharia’ complaint finance, therefore an Islamic bank is expected to provide these solutions.

2. Financially: They are “in an exemplary position in society” (Farook, 2007, p. 32), due to their ability to equitably allocate resources.

The Islamic economic system ensures “property rights, resource allocation and economic freedom” are all maintained (Yousefi et al., 1995, p. 67 citing Khan, 1986; Khan and Mirakhor, 1986). Furthermore, maximising the social benefits rather than solely pursuing profit is a significant objective for Islamic banks (Yousefi, 1995). This is a positive view of the unity, accountability and vicegerent concepts in Islam (Ahmad, 2004; Naqvi, 1994; Yusof and Amin, 2007 found in Azid et al., 2007, p. 12).

The conventional banking theories assume that banks earn profits by receiving deposits from the depositors at a low interest rate, then providing those funds to the borrowers at a higher interest rate (Santos, 2000). Therefore, conventional banks make their profits from the difference between the interest rate received from borrowers and the interest rate paid to depositors. Islamic banking performs the same function but in this system interest is strictly prohibited. That means that they cannot receive a predetermined interest from borrowers and does not pay a predetermined interest to the depositors. The amount of profits is based on the profit sharing agreements with the depositors and also with the borrowers. In addition, there are fee-based banking services that are similar to that practiced by the conventional banks as long as there is no predetermined interest payment or receive in the transaction. Thus, Islamic banking is a separate banking stream as it supports profit-sharing and prohibits interest. The profit sharing depends on the extent of the risk participation of the parties. The absence of pre-determined rewards is based on Quranic orders and as illustrated using Shari’ah principles (Ariff, 1988).

Nevertheless, income and profit are not prohibited in Islam; in fact it is paramount that Islamic banks continue to be profitable; in order for them to continue serving society’s needs. Consequently, Islamic banks are different from charities as charities only distribute wealth. However, Islamic banks have an additional role; to allocate investment according to its potential societal benefit (Farook, 2007).

Moral Filter: Key Product the Islam’s Economic Thought

A key product of the Islamic economics paradigm (stemming from; unity, trusteeship, equity, balance, justice principles) is the moral filter (Rice, 1999). The moral filter includes the prohibition of giving or receiving ‘riba’ (interest), hoarding, speculation as well as not investing or financing industries which are seen as socially negative through Islam such as gambling, tobacco, alcohol or pork.

The Quran is clear in its prohibition of ‘riba’ (interest), “...they say: ‘Trading is only like Riba (usury), whereas Allah has permitted trading and forbidden Riba (usury)” (2:275, also 2: 279). Muslims are only allowed to earn an income or profit when both effort and risk are present, any guarantee of income is prohibited (Lewison, 1999). The prohibition advocates “establishing distributive justice freedom, free from all sorts of exploitation” (Usmani, 2002 cited in Farook and Lanis, 2007, p. 218). Accordingly, Islam views money as purely a medium of exchange, rebutting that interest is a reward for saving, as the reward must only be a consequence of effort and risk taken on in the investment (Rammal, 2006, p. 204). Interest is also prohibited due to its contribution to “social division” (Saidi, 2000, p. 45). This is prohibited by treating the financiers and entrepreneurs as two separate factors of production, as it results in favouring the financier (Rammal, 2006). The argument is that the financier charges interest for the use of money and will demand interest repayments regardless of the success of the entrepreneur’s venture. Saidi (2009) points out that this lack of risk sharing in ventures creates injustice. This is because in the event of the entrepreneur making a loss, the financier will still demands the interest payments (and compounded) to the entrepreneur losing their venture.

Contrastingly, Islam’s economic system treats both capital and entrepreneurs as single factors of production. Therefore, Islamic banking uses a profit and loss sharing (PLS) model, which is equity based. The PLS model works by the financier handing capital to the entrepreneur and in return the two parties will agree that in the event of a profit, a certain percentage of that profit will be returned to the financer. However, in the event of a loss the financier loses their capital and the entrepreneur loses their venture and time. Hence, justice is reached since both risk and return are distributed equitably between both parties (Zaher and Hassan, 2001).

Conversely, the interest based system is not always efficient, as it allocates funds to the most “creditworthy (or collateralized) borrower and not necessarily the most productive project” (Zaher and Hassan, 2001, p. 157). Therefore, societal projects may be overlooked by the capitalist system by not emphasizing collateral and creditworthiness, but by prioritizing worthy projects. The PLS model “will become an efficient model in mobilizing and allocating resources” (Dusuki and Abozaid, 2007, p. 146). So through consistency with the justice objective in Islam, Islamic banks are perfect to support economic growth and advocating financial inclusion by supporting grass roots projects (Khan and Bhatti, 2008). Moreover, as it is in both parties’ interests for the venture to be successful; financiers will have to closely monitor the project, since the productivity of the project determines the level of return on capital.

Literature on Islamic banking and finance has continuously debated whether ‘riba’ (usury) in fact equates to interest (Zaman and Movassaghi, 2002). It is beyond the scope of this study to discuss these arguments, but it is important to understand that debates have led to disparity in Islamic banking practices and consequently disclosures. For the purpose of this study, it is assumed that ‘riba’ (usury) does equate to interest, on the following grounds; “There exists a widespread perception that the ban on riba implies a ban on interest, because this is the prevailing interpretation, we follow it in this paper” (Aggarwal and Yousef, 2000, p. 96). Abu Sa’ud (2002, p. 23-24) also made a similar claim.

Next, we shall discuss the distortion between tenets of Islamic banking and practice, as they both have common grounds. Therefore, are likely to influence disclosure practices of the sample of Islamic banks in this study.

Islamic Banking Practice

Lack of PLS Financing, Instead an Excessive Use of Debt Based Instruments

The lack of Profit-Loss-Sharing (PLS) financing in practice is the key critique of Islamic banking. PLS has represented only 5-15% of all Islamic banking activities, despite being the “purest form of Islamic banking” (Zaher and Hassan, 2001, p. 166); most congruent with Islamic values. Instead, Islamic banks have used debt based instruments such as ‘murabaha’ and ‘tawarruq’ which are less in line with the ‘Sharia’ Law (Dusuki and Abozaid, 2007; Khan and Bhatti, 2008; Walsh, 2007; Kahf, 1999).

Moral hazard issues have contributed to the minimal use of PLS instruments (Yousef, 2000). Deposit guaranteeing laws are found in convention financial systems where Islamic banks operate. These have exacerbated the lack of PLS financing (Walsh, 2007). This distortion between tenets of Islamic banking and practice has risen due to interlinked reasons:

1. Lack of Sharia Supervisory Board (SSB) independence which stem from the lack of standardisation in Islamic jurisprudence,

2. Lack of innovation and financial engineering and the lack of human capital focused on ‘sharia’ complaint finance (Khan and Bhatti, 2008).

The Sharia Supervisory Board (SSB) is responsible for ensuring that the bank conforms to the ‘Sharia’ Law. However, a conflict of interest is apparent, since they are both “independent auditors and inside consultants” (Sorenson, 2008, p. 653). So as banks employ and remunerate their own SSB, it is likely that each Islamic bank’s SSB will interpret the principles of Islam differently. This is due to the SSB of each bank basing their judgements on their respective school of thought (Sorenson, 2008). In effect this could mean what is prohibited or premised by one board may be treated different by another board in another bank (Zaher and Hassan, 2001).

Zaman and Movassaghi (2002) argue the power for the SSB is too freely “determine whether a transaction is or is not Islamic simply points to the lack of consistency and standards in the practices of such banks” (p. 2437). More conflicting debates in the literature due to lack of standards are discussed below.

This conflict of interest has fuelled SSBs to legitimise or approve management’s excessive use of the controversial debt based instruments, such as ‘Murabaha’ and ‘Tawarruq’ (mark-up financing). These are effectively based on conventional finance (Kamla, 2009), as Islamic banking had 54% of its assets as ‘Murabaha’ financing (Khan and Bhatti, 2008). The use of the London Interbank Offer Rate (LIBOR) to determine their “profit rate” and the use of other conventional models has left ‘Murabaha’ to be perceived as a mere ‘resemblance and equivalence’ of conventional debt instruments (Khan and Bhatti, 2008). By using interest based instruments, Islamic Banks are not acknowledging their negative ethical consequences (Kuran, 2004; Patel 2004, found in Kamla, 2009).

Dusuki and Abozaid (2007) explain that although ‘Murabaha’ and ‘Tawarruq’ maybe legally compliant (in form) to ‘Sharia’, it does not make them permissible (in substance/halal). The argument is that substance must prevail over form. For that reason, Dusuki and Abozaid (2007) view ‘Murabaha’ and ‘Tawarruq’ as “devices” (p. 156) designed to bypass the prohibition of ‘Riba’ noting that substance of these mark-up products do not differ from the conventional debt products, although form and structure may be different.

Some scholars note that while they may not be prohibited, their utilisation should be minimised (Siddiqi, 1983 and Khan, 1987 found in Yousef, 2000). Contrastingly, others like Kahf (1999) rebut this opinion, arguing Islamic law has permitted all three modes of financing (PLS, mark-up, lease), therefore it is wrong to favour any as a priority. Furthermore, others like Zaman and Movassaghi (2002) have rejected altogether the basic principle that ‘Riba’ is equivalent to interest. This lack of consensus on what would appear to be “basic” principles of Islam gives leeway for different SSB interpretations.

Moreover, once the basic issues regarding the mechanics of the financial instruments are resolved; there is the debate on whether Islamic banks should have a wider social role other than just providing Islamic instruments. It is claimed that Islamic banks cannot be “distinguished by their social emphases or developmental dimensions” either (Kamla, 2009, p. 925).

Lack of Social Commitment

Dusuki (2008b) found a split in the literature, some believed Islamic banks should have a “socio-economic purpose...promoting Islamic norms and values”; known as Chapra’s model (Dusuki, 2008b, p. 135). Contrastingly, others support the second model (Ismail’s), which is less explicit on the social role of Islamic banks that they should operate to profit maximise, as long as they use Islamic financial instruments (Dusuki, 2008b), any social role should be adopted by governments and charities.

This marginalisation of the social role is also evident in Farook (2007), who categorizes the roles and activities of Islamic banks into:

1. Mandatory activities: Include interest free financial instruments, not to invest in prohibited industries and to pay ‘Zakah’

2. Recommended activities: Include Qard Hassan loans, social impact based investment quotas, supporting SMEs and charitable activities (Farook, 2009, p. 37-44).

Particularly, the recommended form contained social expectations of Islamic banks, such as providing micro finance seen as key to Islamic banking but merely practised.

Khan and Bhatti (2008) note that 95% of the investments and financing are short term, this implies banks are favouring “quick profit” (Kuran, 2004 cited in Kamla, 2009, p. 926) and consumption loans rather than more beneficial long term developments. Moreover, Hassan has accounted to 0.63% of all assets in Islamic banking (Yousef, 2000). This highlights how Islamic banks have not been able to implement financing and investing activities that nurture development and grass root projects with considerable societal benefit (Usmani, 2002, p. 116).

Implications

In their current state, Islamic banks are more driven by profit maximisation, than by pursuing the well-being of society. Dusuki and Abozaid (2007, p. 159) noted how we have a replication of conventional banking model, rather than a fully Islamic model. Kamla (2009) notes how Islamic banking in its current state, not only departs from social role, but contradicts (using debt based instrument) Islam’s holistic objective of achieving social justice, leading to “a gap between the ethical claims of these institutions and their actualities” (Kamla, 2009, p. 926). At least part of the issue is attributed to the conflicting debates taking place in literature itself. After all, literature scholars are also SSB scholars (Farook, 2007).

Basic issues such as whether interest is prohibited as well as the permissibility of using controversial based products have not been ironed out. Hence, leaving the focus on the substance of the products and the social role to be marginalised or ignored altogether. This is likely to be related to the disclosure of Islamic banks in this study.

Islamic Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure

The demand for ISCRD

Certain corners of the literature have criticised social reporting framework for lacking overall coherence (Gray et al., 1995 citing Ullmann, 1985). Even what defines social reporting has been expressed as “murky” (Cooper and Owen, 2007, p. 651) and “[with] no limits” (Nielsen &Thomsen, 2007, p. 26). As mentioned before, Islam has distinguished the right from the wrong and assigned responsibilities from the ‘Sharia’ law. In addition, the key concepts in Islam which were delineated at the start of this chapter allow us to introduce the Islamic corporate social responsibility disclosure (ICSRD) perspective.

The Spiritual Dimension: Social Accountability and Full Disclosure

Baydoun and Willet (1997, p. 82) expressed that the concepts; ‘Tawhid’ (unity), balance (in profit and environment) and equity in Islam have led to social accountability and full disclosure. This view is widely accepted in the literature (Othman et al., 2009; Rizk, 2008; Kamla, 2009; Maali et al., 2006).

A review on accountability and trusteeship in the context of disclosure follows in preparation of introducing the Haniffa and Hudaib (2007) index.

Social Accountability

Accountability in the context of reporting stems from Muslims believing that God takes account of all man’s actions on earth to be used on the day of judgment (Quran, 4:86; cited in Haniffa and Hudaib, 2010 also 4:62 in Rizk, 2004). However accountability to others is not marginalised, in fact being primarily accountable to God, simultaneously implies realising your accountability to others. This relates to Muslim’s relationship to others (Maali et al., 2006). Therefore the primary spiritual accountability to God (and also others), expected of Muslims makes the remit of accountability in Islam more extended than the conventional system.

Full Disclosure

Inseparable from social accountability is full disclosure (Rizk, 2004). The Quran emphasis disclosure: “...mix not truth with falsehood, nor conceal the truth” (2:42 also see 83:1-3). Disclosure is linked to accountability, since the ‘umma’ (mankind) has the right to know how it is affected by the firm’s behaviour (Maali et al., 2006; Rizk, 2008). Full disclosure implies to disclose any information which would be relevant to stakeholders as per the ‘Sharia’ law (Baydoun and Willet, 1999), even if this has a negative effect on the firm (Maali et al., 2006). Therefore, the main objective of disclosure is to enable firms to reflect whether it has adhered to the ‘Sharia’ principles or not (Baydoun and Willet, 1997).

Consequently, Islamic social reporting serves two purposes; firstly it allows stakeholders to evaluate the firm’s social accountability that are required for the stakeholders’ decision-making in order to discharge their spiritual duties (Haniffa and Hudaib, 2002 Harahap, 2003). Secondly, it allows the firm itself to also discharge it’s accountably, to God (primarily) and to the society (Haniffa and Hudaib, 2002). Hence, ISR is an extension of conventional social reporting due to its spiritual dimension (Haniffa and Hudaib, 2010).

Haniffa And Hudaib’s (2007) Csrd Index

This study uses the benchmark developed by Haniffa and Hudaib (2007) to assess the content of social reporting disclosed by Islamic banks. This enables the assessment of whether Islamic banks make full disclosure and are socially accountable as per ‘Sharia’. The benchmark is considered to be more extensive than that produced by Maali et al. (2006) (Napier et al., 2009 p. 128). Haniffa and Hudaib’s (2007) benchmark was also used by Hassan and Harahap (2010) to study CSR disclosure by Islamic banks.

The Haniffa and Hudaib (2007) benchmark reflect conventional CSR dimensions such as employees and environment but is extended to include Islamic specific dimensions such as ‘Zakah’ and SSB, based on the interlinked concepts mentioned before (unity, justice, equilibrium, trusteeship, accountability and social responsibility).

Below, the benchmark that contains the 8 dimensions is discussed, which was developed by Haniffa and Hudaib (2007). Each dimension contains 4-15 elements; the summary of the full list can be found in Appendix 1.

Dimension A: Vision and Mission Statement

Islamic banks have an objective to redistribute and allocate funds for the betterment of the society as they stay in line with the ‘Sharia’ principles; since they are both financial and morally accountable to their depositors (Abul Hassan and Harahap, 2010). Hence, Islamic banks are expected to disclose as their philosophy and values are based on Islamic teachings. Therefore, by disclosing that, the ‘Sharia’ principles are used for guidance for its operations, returns, financing/investment activities, meeting the needs of Muslim communities and showing admiration to shareholders and customers (dimension and elements cited in Haniffa and Hudaib, 2007).

Dimension B: Board of Directors and Top Management:

In order to consider the possibility the board and management will uphold; the criteria of ‘adl, qist (justice) and ihsan (benevolence) disclosures will include a variety of vital information. This will include the name, position, picture, profile and shareholding of both board members and top management. Furthermore, to assess the balance and soundness of the corporate governance structure, stakeholders will expect disclosure of the executive and non-executive split. Also, if there is a role duality by the CEO, limited multiple directorships and if an audit committee all exist (Haniffa and Hudaib, 2007 p. 100).

Dimension C: Product (interest Free and Islamically Acceptable Deal)

The moral filter concept is most evident in this dimension.

Interest Free Products

Due to the ethical concern Islam attaches to interest, financial instruments that are based on Profit and loss sharing (PLS), mark-up and lease are instead expected to be used. Pressures to stay competitive raises concerns with stakeholders who expect the following relevant disclosures; a glossary of instruments used, whether new instruments have been introduced, whether the SSB has approved it prior to its use and whether the ‘Sharia’ was used in this approval.

Islamically Acceptable Deals

Furthermore, the moral filter concept implies that Islamic banks must screen out investing in prohibited industries that deal with pork, gambling, alcohol, tobacco or any other industry deemed as harmful to society or the environment (Beekun and Badawi, 2005). Due to Islam’s prohibition on gharar (excessive/needless risk), Islamic banks may not trade with future market instruments, as it is regarded as unearned profit which Islam prohibits (Wilson 1997). Accordingly, the following disclosures are expected: Any involvement with non-permissible activities and if so, the reason for this, the percentage this activity contributes to profit and how they have been handled (i.e., proceeds for these activities to go to charity) (Haniffa and Hudaib, 2007, p. 100).

Dimension D: Zakah, Charity and Benevolent Loans

‘Zakah’ is an obligatory Islamic duty (paid once a year) as it is one of the pillars of Islam as well as fasting, praying and doing the pilgrimage (Farook, 2007). Every Muslim considers it as a purification of one’s wealth. However, literature has questioned whether ‘Zakah’ is to be paid by the shareholder (individuals) or by the firm (with tax) (Maali et al., 2006; Farook, 2007). Given ‘Zakah’s’ great importance in Islam, disclosure must be made to clarify which of the two are liable to pay ‘Zakah’. If it is the bank, whether it has been paid, the sources of ‘Zakah’ fund, use and balance of the ‘Zakah’ yet to be paid and why this is, SSB attestation the sources and uses are in line with ‘Sharia’ and SSB attestation to verify it’s computation (Haniffa and Hudaib, 2007, p. 101).

Unlike ‘Zakah’, charity (sadaqah) is regarded as voluntary and is part of the social responsibility of Islamic banks. Stakeholders will want to be informed on the Islamic bank’s charitable activities to ensure that they are adhering to the spirit of Islam. Therefore, the following is expected to be disclosed: Amount, sources and uses of charity (Maali et al., 2006; Haniffa and Hudaib, 2007).

Qard Hassan has an interest free loan prioritised for social projects such as building hospitals or schools, rather than for consumption and luxuries. Thus, it will be expected to find disclosure on the amount, sources and the policy used to decide which project is to be funded and what would happen in the event of failure to pay (Maali et al., 2006, p. 274; Haniffa and Hudaib, 2007, p. 101).

Dimension E: Employers

Equal opportunity in employment is advocated when hiring employees and has been categorically addressed by Prophet Muhammad (Beekun and Badawi, 2005) and stems from the Islamic principle of unity and equality (Rice, 1999). Employee’s welfare must be looked after and adequate rewards must be given as this relates with ‘ihsan’ (benevolence) in Islam (Beekun and Badawi, 2005). Given the above, it is expected that concern for employees is disclosed by the following elements; appreciation of employees, number of employees, equal opportunity, employee welfare and reward, ‘Sharia’ training and human development, training for graduates and amount spent on training (Haniffa and Hudaib, 2007, p. 101; Maali et al., 2006, p. 276).

Dimension F: Debtors

The use of mark-up and lease instrument causes a risk that debtors will be unable to pay what is due. Islam has categorically remedied this situation through the perspective of ‘ihsan’ (benevolence), “if the debtor is in a difficulty, grant them time till it is easy for them to repay” (Quran 2:280, cited in Maali et al., 2006, p. 276). Therefore, it is mandatory that Islamic banks extend the time for repayment with no extra charges (Farook 2007), preferably write them off as bad debt. As a result of this, there is an expectation of Islamic banks to disclose their debt policy and how much has been written off, as well as the type of debt being lent (Haniffa and Hudaib, 2007, p. 101).

Dimension G: Community

Islamic banks have an emphasised responsibility to partake in community and social activities that are focused towards the society. Likewise, they need to prioritise investments and financial support to sectors that meet the needs of society (Maali et al., 2006). Hence, it is expected that the Islamic banks will disclose the following; their commitment towards their social role, whether they created new jobs, their support to organisations that bring benefit the society as well as government social activities. Also, whether they sponsored community projects or held any conferences on Islamic economics (Haniffa and Hudaib, 2007, p. 102).

Dimension H: Sharia Supervisory Board (SSB)

As an internal corporate governance mechanism, members of the SSB should be ‘Sharia’ jurists or scholars to best “enhance the credibility of the institution” from an Islamic perspective (Rammal, 2006, p. 205). Hence a SSB report is expected to disclose whether the banks operations and activities conform to the ‘Sharia’ and that this report is signed by each member of the SSB. Furthermore, the following disclosures would be expected: Names, pictures and remuneration of the members, number of meetings held, business transaction examined both ex ante and ex post. Additionally, whether the examination was on at all or on a sample basis, report of any defects in products, any recommendations from the SSB to rectify this defect, whether management took any action to rectify and whether distribution of profit and loss was complaint with the ‘Sharia’ (Haniffa and Hudaib, 2007, p. 102).

In summary, Islamic banks whom disclose much of the dimensions and their elements listed above, appreciate the Islamic central concepts of full disclosure and social accountably. Appendix 1 has the summary of the 8 dimension and their respective elements.

Sample and Research Methodology

Selection Criteria

As a Justification of the choice of an Islamic bank in UK, there are few studies that focused on social reporting by Islamic banks and all focused on the Arabian Gulf or other Muslim countries; where poor CSR disclosure has been inarguably the consensus or status quo. This means that there were no studies focused on any western Islamic banks, let alone the UK. This is the reason this study chose the Islamic banks in UK.

A combined selection criteria is used:

1. Fully Fledged Islamic Banks: Our population is fully fledged with Islamic banks in the UK and not Islamic windows in conventional banks.

2. IFSL as source: The International Financial Services London (IFSL) “Islamic Finance 2009” report used to determine population.

The IFSL report identified 22 banks that were either Islamic windows or that were fully fledged in the UK. 22, 5 were fully fledged Islamic banks. They are; Islamic Bank of Britain (IBB), Bank of London and Middle East (BLME), European Finance House (EFH), European Islamic Investment Banks(EIIB) and Gatehouse Bank(GB). As EFH is a subsidiary of a parent bank in Qatar, it did not have a separate annual report and its reporting entity is based outside our UK control group, therefore EFH was excluded. GB was included in our sample even though it has one annual report, due to the bank opening in 2009, its inclusion will be carefully managed; both in presenting the results clearly show the effect of including GB and when evaluating them.

Annual Report

To assess the practice of CSR disclosure of the 4 Islamic banks in our sample, a longitudinal (from 2007-2009) content analysis of their annual reports was performed, all accessed via their respective websites.

According to Tilt (1994, cited in Unerman, 1999), annual reports are perceived by stakeholders as both a robust and primary source of information, due to their credibility as well as their ease of accessibility. Nevertheless, it has the ability to show both what is and is not disclosed (Adams and Harte, 1998 cited in Unerman, 1999). According to Unerman (1999, for list of papers see p. 668) CSR literature has made extensive use of content analysis to determine the level of CSR disclosed in annual reports.

Content Analysis

Content analysis is used to evaluate the disclosure practices in texts according to dimensions and their elements, which are predetermined by the researcher. The aim of content analysis is to transform text enabling “replicable and valid inferences from texts to the contexts of their use” (Krippendorff, 2004, cited in Beck et al., 2010, p. 207). Beck et al. (2010, p. 208) broadly categorise content analysis in to two:

1. Mechanistic: This can be form orientated: Counting words, sentence pages or Meaning oriented: Emphasising on the “underlying themes in the texts” or;

2. Interpretative: Based on discourse and rhetoric analysis, it aims to “gain understanding of what is communicated and how concerned with quality, richness or qualitative character of the narrative”.

This study uses the mechanistic form, as it is used more widely than the interpretative method (Beck et al., 2010). Moreover, the meaning method gives us more information therefore better conclusions on disclosure can be made, due to its greater interpretative character (Beck et al., 2010).

The Haniffa and Hudaib (2007) benchmark of disclosures used in the study; is a mechanistic one. We use the same 77 elements under the same eight dimensions, as our “coding (or checklist) scheme” (Aribi and Gao, 2010, p. 77), summary of list (Appendix 1). The study benchmarks gave annual reports against these dimensions.

Scoring System

Like most benchmark studies, a “dichotomous index to analyse the content of disclosures” (Beck et al., 2010, p. 208) is used. In other words, a coding system is deployed, where if an annual report discloses a predetermined element from a predetermined dimension, 1 is recorded against that element. If no meaningful disclosure is made for that particular element, 0 is recorded against it. The scorings will be then aggregated, reflecting the level of disclosure according to the predetermined index of dimensions and their respective elements.

All the elements have been given equal weights, to avoid any arbitrary effect (Barrett, 1876, cited in Maali et al., 2006). In terms of methodological issues; validity issues are not applicable since there are no multiple researchers. The issue of reliability is mitigated by the use of dichotomous codes (1 or 0) (Weber, 1985).

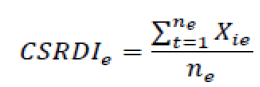

To evaluate the level of disclosure an index is used named the Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure Index:

CSRDLe is the Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure Index, ne the number of items disclosed by eth bank, ne ≤ 77 and xie=1 if ith item is disclosed, 0 if ith item is not. In other

words (as per Haniffa and Hudaib, 2007, p. 104),

(as per Haniffa and Hudaib, 2007, p. 104),

This will enable the ranking; the higher the CSRDI the more the dimension/bank is conforming to the index and thus the ‘Sharia’ (Beck et al., 2010, p. 208). Results and discussion follow.

Disclosure Analysis and Evaluation

The discussion for this part is split in two: Overview of the disclosure by the banks and dimension-by-dimension analysis.

Over View of Banks Disclosure

Looking firstly at the three banks with 3 years of annual reports; the results show that none of the 3 banks have achieved higher than average (50%) Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure Index (CSRDI) scores. Over the 3 years EIIB was the highest scoring bank (46%), second was BLME (44%) and last was IBB (39%). This indicates that the Islamic banks in this study have failed to fully disclose as per the benchmark developed by Haniffa and Hudaib (2007).

Overall the 3 UK Islamic banks disclosures fell below what is expected by stakeholders and more importantly the ‘Sharia’ (Islamic law).

GB’s one year (2009) results managed to average CSRDI with 58%. This score is more appealing when you compare it to BLME’s 2007 score of 39% (its first year in operation and the only bank of the three to have a first year in our study). In addition, it was claimed by Haniffa and Hudaib (2007) that Islamic banks in their first year of operation would disclose extensively; as they set out to reflect their business objectives. This can explain GB’s over the average performance. However, as we do not have GB’s (2nd) 2010 annual report we are unable to confirm this. Although, BLME’s improving disclosure trend is used to give a little support to Haniffa and Hudaib’s (2007) above argument as the trend was consecutive since its first year (2007).

It is worth mentioning that GB categorically addressed the issue of disclosure and transparency; indicating that they have a clear appreciation of the full disclosure and accountability concepts found in Islam:

1. “Disclosure and transparency are important issues that we incorporate into all our business dealings”(Gatehouse Bank Annual Report, 2009, p. 3).

Dimension by Dimension Disclosure Analysis

Dimension (A): Vision and Mission Statement

Firstly, considering the three banks with three years of annual reports (BLME, IBB and EIIB), the bank with the highest CSRDI score for the 3 years average was EIIB (74%), second IBB (56%) and third was BLME (48%). GB scored 67% for the dimension for its single year (2009). The dimension ranked 2nd highest due to the 3 years overall average disclosure.

Nonetheless, every bank in all the years disclosed that they seek to operate according to the principles and ideals of the ‘Sharia’ Law. A similar result was found with Abul Hassan and Harahap (2010). This can be regarded as the basic expectation that stakeholders would have done. Evidence like the one below was echoed in a similar fashion throughout all the banks over the years:

1. “EIIB is committed to excellence in the delivery of sharia complaint investment banking products and services” (EIIB Annual Report, 2009, p. 1).

Moreover, all the banks in the majority of years disclosed that they maximised shareholder wealth. However, similar to Haniffa and Hudaib (2007) findings, there was no mentioning of maximising shareholder wealth in an “Islamic” or “halal” manner. This affirms the arguments that Islamic banks are inclined towards being solely profit driven, differing little from conventional counterparts (Zaman and Movassaghi, 2008; Khan and Bhatti, 2008).

Current and future commitments to serve the needs of the Muslim community were addressed only by IBB in 2008 and 2009 by EIIB. However, only in 2007 they affirmed arguments from the literature that Islamic banks marginalise their social commitments (Kamla 2009; Pollard and Samers, 2007). Nevertheless, EIIB’s disclosure was emphasised by disclosing the element under its “Objectives and Market environment” heading:

1. “The current Muslim population worldwide is estimated at 1.3 billion of which approximately 90 million live in Europe and Turkey...we believe that Islamic financial products have the characteristics to meet this demand”(EIIB Annual report, 2007, p. 8).

This strong commitment from EIIB did not continue in the subsequent years (2008 and 2009) as they were indicating inconsistencies.

In terms of commitments to “halal” (permissible) investments and financing, only EIIB disclosed this for the full 3 years. Although in 2009, both GB and IBB disclosed the element. Interestingly, the IBB who included “Sharia compliance risk” as one of their risks alongside credit and market risk sent a pro-active message. EIIB used a contrasting yet equally effective method; stating the Quran as their source for identifying permissible activities, as they were the only bank to do so.

Disclosure of appreciation to customers and shareholders was made by all banks for all years. Most of them were explicit in their disclosure, similar to the following example:

1. “Finally, I would like to thank Islamic Bank of Britain’s customers, employees and shareholders for their continued support and commitment to the Bank” (IBB Annual report. 2008, p. 6).

This evidence rebuts that Islamic banks have “little concern for customer satisfaction” (Kahf, 1999, p. 17); evidence shows that at least on a disclosure basis, this is not the case.

Dimension (B): Board of Directors and Top Management

For this dimension, only BLME increased its disclosure year on year, while both IBB and EIIB both disclosed less in their last years in comparison with their first year, indicating a lack of consistency.

The overall average for the 3 years for the dimension was 52% for the 3 banks, adding GB made no impact to this figure, with the dimension being ranked 3rd amongst other dimensions. Disclosure on Board of directors’ elements made up most of the score rather than top management.

Elements identifying who the board of directors were names, positions and profiles. These were disclosed by most banks in most years. Other elements were: Composition (executive/non-executive), shareholding, their multiple directorships and whether an audit committee existed were disclosed by all banks in most years.

Unfortunately the high levels of disclosure regarding the boards cannot be continued onto the management elements. Only BLME in 2009 disclosed any elements (4: Names, positions, pictures and profile) regarding top management.

Haniffa and Hudaib (2007) and Abul Hassan and Harahap (2010) found that in the Arab gulf region disclosure on both Board and top management (corporate governance) to be “lacking”. However, this study can only support the above argument in the context of top management because there were virtually no disclosures found. But in the context of Board members relatively extensive disclosure was found. Perhaps this latter finding is attributed to the better corporate governance structures, which are generally found in developed countries (Khan, 2010; Maali et al., 2006; Douglas et al., 2004).

Dimension (C): Products

BLME and EIIB both had inconsistent disclosure on this dimension, while IBB improved (in 2008) then maintained (2009) its level of disclosure for this dimension.

The overall average CSRDI for the 3 years for the 3 banks was 48%. This was decreased by 1% when GB is concluded. The inclusion made no difference to the ranking of the dimension which was 4th.

All the banks in all the years disclosed that they had no involvement in non-permissible activities. Although at times this was implicit and difficult to ascertain (found also by Haniffa and Hudaib, 2007). None of the banks at any period disclosed the proportion of profit that came from impermissible activities or even the reason for involvement. After a similar result, Maali et al. (2006) explained how Islamic banks may be aware of the negative image this disclosure can portray; undermining the full disclosure expectation.

Disclosure is crucial regards any new products, moreover, whether this has been approved by the ‘Sharia’ supervisory board or not (SSB), before being used and whether the ‘Sharia’ was used as the basis of this approval. Results show that none of the banks at any time sought prior SSB approval before marketing their new products. The lack of reviewing all transaction ex ante has been noted by Rammal (2006, p. 206); in practice approval by the SSB, due to it being seen as a “routine matter with SSBs approving decision already made by the bank’s management”. This result confirms the lack of independence the SSB has from its management. This was noted earlier in the literature review section (Khan and Bhatti, 2008; Kamla, 2009; Sorenson, 2008).

All banks (apart from GB) throughout the years had disclosed a glossary on the products they were marketing. This is beneficial to annual report users who were not familiar with the Arabic language (Haniffa and Hudaib, 2007), particularly relevant to the current based UK study. The near 100% disclosure of this element was contrastingly better than the below average (50%) result found by Haniffa and Hudaib (2007). Perhaps this was due to Haniffa and Hudaib’s (2007) sample being based in an Arabic speaking region; where it may have been seen as less useful.

In line with Haniffa and Hudaib’s (2007) findings, results showed that all the banks in all years disclosed on general investment activities; different from Haniffa and Hudaib (2007). Contrastingly, all our banks throughout the years disclosed in general terms the projects they financed. GB made perhaps the most extensive disclosure to the different finance, investments projects and activities out of all the banks. Saidi (2009) theorised that Islamic banks need a “supply of information on all projects and investments that depositors’ money is used for “(p. 46). Accordingly, in the case of IBB, the bank disclosed that its ‘Mudarabah’ saving accounts used “Profit stabilisation reserve” to eliminate the risk being associated with deposits:

1. “In the case of inadequate returns generated by these funds, the Company will maintain the return to depositors by utilising this reserve” (IBB Annual Report, 2009, p. 19).

Additionally, the stakeholders will be able to make their own judgement regarding this disclosure and whether it undermines IBB’s initial claim of abiding to the ‘Sharia’ principles. However, this disclosure would not be a surprise to some stakeholders given that by law, retail banks in the UK must insure their deposits.

Dimension (D): Zakah, Charity and Benevolent Loans

Each year, both BLME and IBB kept disclosing at 7%, in other words they disclosed only one (same) element out of the 15 element in that dimension. EIIB disclosed 15% on average over the 3 years, increasing its score in 2009. The yearly average for the dimension was 10% and adding GB made no difference. Furthermore, this minimal disclosure constituted mainly of the banks disclosing whether they were liable on ‘Zakah’ or not, marginalising other ‘Zakah’ elements, ‘Sadaqah’ or ‘Qard’ Hassan elements.

Although ‘Zakah’ is an obligation on all Muslims (Quran 9:103; Rice, 1999), there is debate among scholars whether this applies to corporations or shareholders. As the banks disclosed they were not responsible to pay the ‘Zakah’, it meant they also failed to disclose other ‘Zakah’ related elements. Other ‘Zakah’ related elements were: Sources of ‘Zakah’, amount paid, beneficiaries and whether there was a balance.

Since all the banks disclosed not being liable to pay ‘Zakah’, shareholders will place great expectations on the banks to disclose; the amount shareholders are liable to pay and whether the SSB has confirmed this calculation or not. In fact, minimal disclosure was made, only EIIB (did so in all 3 years) and GB (in it’s one year) provided the amount the shareholders are liable for, while only GB went on to disclose SSB attestation.

The second half of the dimension; charity (Sadaqah) and benevolent loans (Qard Hassan) witnessed near zero disclosure by all the banks in all years. Only IBB (in all 3 years) made a disclosure on its sources of charity, which was from late payment fees they charged their customers (as per the ‘Sharia’ any late payments charges received must be paid to charity; Walsh, 2007). This minimal disclosure is constant with Abul Hassan and Harahap (2010), but contrary to Maali et al. (2006). Moreover, none of the banks at any time disclosed any of the elements regarding Qard Hassan (amount, source and policy), in line with Maali et al (2006).

In addition, it is clear that Islamic banks have lacked sufficient disclosure on this dimension as a whole, especially on the charity and benevolent loans half of the dimension. It is no surprise then that this led to the dimension being ranked bottom with an overall average CSRDI of just 10% (when including GB). Further, literature (Farook, 2007) claiming that ‘Qard’ Hassan is “recommended” rather than “mandatory” affirms or mirrors the general marginalisation of Islamic banking social role.

Dimension (E): Employees

The employee dimension achieved an overall 3 year average disclosure of 46% between the three banks (BLME, IBB and EIIB) adding GB’s one year result (56%) increases this result to 47%, pushing the dimension one rank, to 4th best dimension.

GB’s distinctly better score was supported by them disclosing a dedicated “Employee Consultation Group”, ultimately contributing to employee welfare. Furthermore, they provided Continuous Professional Development (CPD) courses in partnership with an investment oriented professional body.

Disclosure on the ‘Sharia’ focused training was limited as out of all the four banks only BLME disclosed the element (2008 and 2009), encouraging all its employees to undertake Islamic finance training. The lack of disclosure by the rest of the banks on ‘Sharia’ training will raise concern, as it is considered paramount for the Islamic bank’s ability to meet its goal in operating in a ‘Sharia’ complaint manner (Choudhury and Hussain, 2005).

The poor training score was not in line with Haniffa’s and Hudaib’s (2007) study, which had 4 out of 7 banks disclosing this element. The lack of disclosure on this element is reflected in the literature, where it has been noted that there is a lack of human capital, equipped with ‘Sharia’ training, especially in non-Islamic countries. Therefore, this has been justified on the grounds of the sectors’ infancy (Kahf, 1999; Khan and Bhatti, 2008). Overall, human development (both ‘Sharia’ and general) disclosure has been scarce. This was exacerbated by the fact that zero disclosure was made from all banks regarding the amount they spent on overall training. The lack of focus on human development found in this study supports the evidence found by Aribi and Gao (2010).

Instead, much of the 46% 3 year average disclosure in this dimension attributes to the high levels of disclosure on the elements. Examples are these elements are: Employee appreciation, reward, welfare (pensions, share options) and the number of employee’s.

Contrastingly, none of the 4 banks in any year made disclosure on whether they had an equal opportunity policy; this was similar to the findings found in Aribi and Gao (2010). Given that justice and no discrimination are well enshrined in Islam, this result is out of touch with expectations. The result is mystifying, as Farook (2007) had classified that employee justice would be a mandatory activity, while the welfare and appreciation issues would be voluntary, our results contradict this view.

Dimension (F): Debtors

As the top ranked dimension overall, the dimension had a 3 year average of 92% between the three banks, adding GB made it 90%. Strikingly, a similar result was found by Haniffa and Hudaib (2007), who also found this dimension ranked top. However, what was disclosed shows evidence of Islamic banks not abiding to ‘Sharia’ principles; which is contradictive to their claims in the first dimension.

IBB and GB where the only 2 banks not scoring 100% (BLME and EIIB achieved 100%) disclosure in this dimension with 75% (3 out of 4) for all their years. This was the result for them failing to disclose the type of lending activities in detail, although, they did so in general terms.

All the banks disclosed their debt policy; unfortunately this full disclosure revealed that Islamic banks did not adhere to the ‘Sharia’s’ call.

This was supported by the evidence; the demand for collateral in financing as this was demanded by all the banks throughout the years:

1. “The Company holds collateral against secured advances” (IBB Annual report, 2009, p. 24).

2. “The Bank obtains collateral in respect of customer liabilities…and gives the Bank a claim on these assets for both existing and future liabilities”(BLME Annual Report, 2009, p. 38).

Unlike the other 3 banks, GB did not disclose any collateralised or secured financing. GB’s relatively better image as an Islamic bank is demonstrated when compared to the other three banks.

The conventional framework of risk management deployed by all the banks by demanding collateral triggers two (direct and indirect) breaches of the ‘Sharia’:

Direct: Demanding Collateral in Itself is Prohibited

Banks expecting collateral or securing their financing is prohibited under the ‘Sharia’ laws:

1. “It appears that much of the ‘lending’ done by Islamic banks is secured, violating a legal prohibition on collateral” (Aggarwal and Yousef, 2000, p. 94).

Indirect: Demanding of Collateral Prevents (Indirect) “Good Projects”

Similar to the conventional banks and contrary to the ‘Sharia’, all the Islamic banks in this study have used ‘creditworthiness and collateral’ as integral elements to their framework for risk management and debt policy:

1. “This resulted in the exiting of several credits that had become higher risk. It also prompted an increased focus on domestic, higher rated, shorter term and better collateralised business within a framework of reduced concentration risk”(BLME Annual Report, p. 3).

2. “We will maintain tight cost control and focus on growth in low risk secured customer finance assets” (IBB Annual Report, 2009, p. 5).

The evidence affirms the Islamic banking critique (discussed in section 2.3.2) of short terms, obsession with risk appetite and more importantly, their failure to prioritise other factors. An example of these factors are long-term projects that are of most benefit to society (Dusuki and Abozaid, 2007; Khan and Bhatti, 2008; Zaher and Hassan, 2001 and Saidi, 2001). The excessive focus on collateral could mean banks financing “creditworthy borrowers and not necessarily the most productive projects” (Zaher and Hassan, 2001, p. 157).

Practical examples such Grameen bank in Bangladesh; notable for its successful micro financing, have shown that in fact, Islamic banks can overcome such challenges by working closer with their clients and adopting a risk management framework more in line with the ‘Sharia’ objectives (Kamla, 2009).

Despite the extensive negative debt policy disclosed by the banks in this study, positive debt policy was disclosed by EIIB showing commitment and cooperation towards a debtor who is in ‘doubt’ to making full payment;

1. “We are actively working with the obligor to relive the situation...” (EIIB Annual Report, 2008, p. 3)

According to Kamla (2009) more cooperation with debtors; as shown by EIIB, would ensure success for Islamic banking in its most ideal form. Unfortunately, EIIB were inconsistent as they were unable to repeat such claims neither in 2007 nor in 2009.

All the banks throughout the years excelled in disclosing debts written off, in terms of impairments and provision. This disclosure is favourable since Islam advocates debts to be pardoned, in accordance to the benevolence concept.

Dimension (G): Community

Due to their unique position, Islamic banks should realise their social role as being their prime objective (Dusuki, 2008). The community dimension achieved a 3 year overall average of 7% for the three banks (BLME, EIIB and IBB). Indeed they were the lowest ranked dimension.

The lack of overall disclosure on social issues such as; financing SME and social impact based investments by the three banks, mirrors the general marginalisation of the Islamic banks social role. For example, the categorisation of the social roles as “recommended” mentioned earlier (Farook, 2007).

When including GB’s one year result (100%), the dimension’s overall average leaped one rank from bottom, as its overall average moved from 7% to 25%. By far, GB’s greatest impact (or contrast) on the 3 banks was found in this dimension.

GB’s remarkable result of 100% meant all the 6 elements belonging to the dimension were disclosed. Under a dedicated CSR section, GB disclosed it and worked with not-for-profit organisations and governmental initiative (MOSAIC) that supported community projects which were focused on education and social welfare. They also made social investments, for example; originating the SAM-Gatehouse Islamic Water Fund; which was aimed at reducing water scarcity across parts for the world. Their commitment to the social role was clear:

1. “Gatehouse fulfils its CSR obligations through an ethical approach to investing and support of not-for-profit organisations. CSR is viewed as an integral component of the Bank’s corporate governance framework and is a standing agenda item on the monthly Operating Committee” (GB, 2009 Annual Report, p. 9).

Haniffa and Hudaib (2007) also found this dimension to be disclosed the least. Moreover, the lack of social focused elements witnessed here, supports claims that Islamic banks in practice have been less in line with ethical values enshrined in Islam. Therefore, are instead more in line with conventional systems (Kamla, 2009; Dusuki, 2008).

Dimension (H): Sharia Supervisory Board (SSB)

This dimension focused on the disclosure regarding the internal SSB and its report, both served the role of providing confidence that the bank’s operations and activities are ‘Sharia’ complaint. Despite all banks either sustaining or increasing their disclosure year-on-year; the three year average for the three banks was low, at 30%, leaving the dimension’s performance 3rd from bottom. Including GB’s one year result was not material enough to increase the dimension’s rank.

Although Haniffa’s and Hudaib’s score (47%) for the SSB dimension was below 50% (average), the dimension ranked them 2nd best in their study, compared to this study which was 3rd from bottom. The scores ranged from 21% (IBB) to 36 % (BLME), although including GB it stretched to 55%.

Needless to say, the general result is likely to give little confidence to the stakeholders; as the lack of disclosure threatens the legitimacy of the Islamic bank as being congruent to the ‘Sharia’.

IBB, EIIB and GB, had consistent full disclosure on the names of the SSB members. Similar results were found in Haniffa’s and Hudaib’s study (2007). In contrast BLME only disclosed names of their SSB once in the second year, illustrating inconsistency.

Moreover, none of the banks in any of the years disclosed how many SSB meetings were held, undermining their accountability.

Only EIIB disclosed that their SSB used a sample to examine whether all business transactions conformed to the ‘Sharia’ principles or not. The other three banks examined all their business transaction. Furthermore, those three banks only examined the transactions ex post; after the products have been in use, rather than ex ante; before the transactions were made. The lack of reviewing all transaction ex ante has been noted by Rammal (2006, p. 206); in practice audit of the accounts by the SSB is seen as a “routine matter, with boards approving decision already made by the bank’s management”. This confirms the lack of independence which was found in Islamic banking practices between the SSB and management (Khan and Bhatti, 2008; Kamla, 2009 and Sorenson, 2008).

Although none of the SSB reports disclosed any specific details on any defects in operations, both EIIB in 2008 and GB, provided recommendations to rectify defects in products. Only GB went on to disclose that management took action to rectify this.

1. “The SSB identified some minor discrepancies in its findings in relation to business expenses, which the Bank has addressed through further internal controls and systems.”(GB, 2009 Annual Report, p. 10).

Interestingly, IBB was contradictive in its disclosure. On one hand, the SSB report made it clear that no defect were present:

1. “In our opinion, the transactions and the products entered into by the Bank during the period from 1 January, 2009 to 31 December, 2009 are in compliance with the Islamic Sharia rules and principles and fulfil l the specific c directives, rulings and guidelines issued by us”(IBB, 2009 Annual Report, p. 6).

2. “Donations to UK charities amounted to £1,200 (2008: £2,023) and consisted of late payment fees received on personal finance accounts that were paid to charity in accordance with product terms as agreed with the Sharia Supervisory Committee”(IBB, 2009 Annual Report, p. 9).

The first sentence highlights the conformance with the ‘Sharia’ principles, while the second shows how some revenue was non-permissible under ‘Sharia’ principles. In addition, that management was advised by SSB to pay them to charity; this occurred both in 2008 and 2009. Remarkably, an identical scenario was found in Haniffa ‘sand Hudaib’s study (2007); perhaps implying this is common practice.

Conclusion and Implications

Conclusion

Rather than solely pursue profit maximisation, Islamic banks are expected by ‘Sharia’ (Islamic law) to apply a moral filter when financing and investing as well as fulfilling their role of distributing and allocating investments. This objective is derived from the Islamic economic paradigm.

Using content analysis, the objective of this study was to compare the communicated versus the expected CSR disclosure made by four UK Islamic banks. The study used the disclosure index developed by Haniffa and Hudaib (2007) for Islamic banks, as the expected disclosure benchmark. Similarly, with the current trend, the results found that communicated disclosure made by the Islamic banks fell short of the expected or ideal disclosure set out by the benchmark. All the 3 banks that had three year results had a 3 year average CSRDI score of below average (50%); BLME(44%), IBB(39%) and IBB(46%). In line with the current trend from the literature, the dimensions; commitments to society and management of ‘Zakah’, charity and benevolent loans were communicated the least. If it had not been for GB’s one-year distinct and positive result on community elements, the results would have been bleaker.

Although dimensions such as debtors were fully disclosed, what was disclosed showed little consideration to Islam and the social role. Indeed disclosing the use of collateralised secured and short term instruments affirmed that UK Islamic banks are chasing “big business status” (Pollard and Samers, 2007, cited in Kamla, p. 926).

Overall the result shows minimal disclosure meaning that the trend of poor disclosure among Islamic banks in Muslim countries (where most studies were focused) is supported by UK Islamic banks, leaving the status quo of poor disclosure unchallenged. The result is surprising since the Islamic banks are expected to be socially accountable. Therefore, make full disclosures in order to fulfil the accountability placed onto them by God (primarily) and thus also mankind (stakeholders).

Implications

This result has implications on managers, standard setters and Limitations and future research:

Managers

As the results show inconsistency (between dimensions) and at times contradictions, two possible remedies are outlined to allow managers to be more in line with expectations. Firstly, managers should ensure they adopt a consistent reporting style (terminology, rhetoric and strategies all aimed in one direction, Nielsen and Thomsen, 2007 p. 39). This one direction for Islamic banks can be pointing towards discharging their accountability and full disclosure. This ‘one direction’ is also compatible with the ‘Tawhid’ (unity) principle. Secondly, Islamic banks need dialogue with their stakeholders in a way which facilitates the challenges of different views. This has been “identified in the literature as relevant for improved accountability” (Cooper and Owen, 2007, p. 652).

Standard Setters

The lack of disclosure found in most studies on Islamic banking, including this study, have been fuelled by:

1. There is a wide interpretation of responsibility among Islamic banks and their SSB, some marginalise the social role and focus instead on the narrow role, the legal technicalities of avoiding ‘Riba’ and speculation (Farook, 2007).

2. An “expectations gap” is present where some Islamic banks in fact play their social role, but fails to disclose this (Farook, 2007).

3. Unique to this study, the low disclosure may be attributed to the fact that the ‘relevant public’ (Muslims) compromise a small proportion of the UK’s population (1-2%), thus there is a lack of pressure on Islamic banks. This was found to be a significant factor in disclosure (Farook, 2007; Maali et al., 2006).

Accordingly, the introduction of a majority consensus in the shape of a standardised regulatory framework will have a better effect on the “credibility, transparency and disclosure” of Islamic banks (Khan and Bhatti, 2008). The standardisation will allow for ‘Sharia’ codifications’ as well as a ‘common platform’ for SSB. Both would mitigate the risk of the SSB interpreting the ‘Sharia’ in favour of their management to approve the use of controversial products and the marginalisation of their bank’s social role (Kahf, 1999, p. 16).

However, if the management and standard setters take the necessary steps to narrow the current detachment of Islamic banking from the “substance and spirit of Islam”, this will mean that the industry will run the risk of losing support and legitimacy (Kamla, 2009, p. 931).

Limitations and Future Research

The results presented by this study are subject to a number of limitations. Firstly, research should take on a larger sample, especially across the Western world. Secondly, Islamic windows (i.e., Islamic branched of conventional banks like HSBC Amanah) as well as other Islamic Financial institutions (e.g. insurance companies) can be examined to assess whether the current trend of poor CSR disclosure is found in those institutions or not. Thirdly, the study compared communicated versus the expected. This illustrates that studies in the future comparing actual versus communicated will help highlight the validity of the communicated disclosures. Fourthly, the use of annual reports does not capture the full picture of the extent of CSR disclosure made (Unerman, 1999), hence other media (internet, newspapers, etc.) as well as conducting interviews. In terms of methodological issues; the study used a dichotomous index. However, the use of more sophisticated indexes for example; that can record the quality or the nature of news (good or bad) can “add richness of the data captured” (Beck et al., 2010, p. 208).