Research Article: 2018 Vol: 22 Issue: 3

An Inquiry into Improving Women Participation in Entrepreneurship in Turkey

Meltem Ince Yenilmez, Yasar University

Abstract

This research examines female small business owners who run and operate companies and start-ups in two different cities in Turkey; Istanbul and Izmir. The research takes a look at the challenges women face in founding and running their businesses and how to manage work-family conflicts that arise. By taking a look at the level of progress of Turkish female entrepreneurs, the research draws a line between the differences and similarities between female entrepreneurs in Turkey and those in developed countries and seeks to find how their venture into entrepreneurship affects their cultural social and economic standing. This is primarily an exploratory research, and therefore the findings are peculiar to female entrepreneurs in the two cities mentioned earlier. The research hopes to serve as an eye opener and a guide to further research. The research presents its findings and recommendations that could be carried out by government and implemented as government policies to encourage other women to go into entrepreneurship. One way government can go about this is to increase the number of spaces for women in social, economic, cultural, legal and political sectors, as these will improve the chances of women becoming employers of labour.

Keywords

Women Entrepreneurship, Enabling Factors, Opportunity, Prospects.

Introduction

Entrepreneurial leadership cannot only be determined by technical expertise, as it is more of a psychological approach than an attitude. The rising number of entrepreneurs and start-ups worldwide has led to a rise in interest from international organization, scholars and government officials about the connection between economic development and entrepreneurship. (Garnder et al., 2014). In addition, the small and medium scale enterprise represents over 90% of the entire companies in the economy (Ranjan, 2016). Studies have shown that getting conversant with the right skills are important for women before they venture into entrepreneurship. Hypothetically speaking, the number of entrepreneurs should be on the rise when there is enough interest in entrepreneurship (Phipps et al., 2015).

Skills like physical, spiritual and mental preparation, ability to both read and comprehend financial statements, cautious design of business and private life, business growth development, maintaining and increasing the joy associated with doing business and learning the ability to delegate and multitask. Though entrepreneurship has a major role as a catalyst for economic development in developing and already developed countries, prior research focused solely on the United States as well as other developed countries (Çetindamar, 2005; Gupta and Ranian, 2009) therefore, proven field knowledge has been restricted to the world’s English speaking sections (Karataş-Özkan et al., 2010). The same can be said concerning the study on the entrepreneurship of women, as field researchers have typically been carried out in already developed countries (Welter et al., 2006; Çetindamar et al., 2012). In the same vein, they are a lot more men in leadership positions than they are women (Radovic-Markovic et al., 2016). Considering the fact that women entrepreneurs are labelled as extremely imperative yet untapped foundation of the developing world’s economic development and growth (Minniti and Naudé, 2010; Vossenberg, 2013), only a small number of research (Javadian and Singh, 2012) has at this moment looked into the entrepreneurship of women in developing countries such as Turkey.

The proposal for gender equality stems from both economic and human rights arguments. Intrinsically, reducing gender gaps should play a major role in any policy to generate a more inclusive and sustainable society and economy. Increased participation in education, starting from a very early age, offers women improved economic chances by increasing the general level of labour, productivity and human capital. Increased gender diversity is surely going to encourage competitiveness and innovation in business. Increased women economic empowerment and better gender equality concerning leadership are major components of a broader gender initiative to formulate policies for better, fairer and stronger growth in already developed and still developing countries alike. Then again, when women are placed in powerful positions, it motivates other women as they seek to emulate them by getting leadership roles.

The studies concerning women entrepreneurs, especially in emerging countries, are rare (Allen and Truman, 1993). It actually presents a problem in comprehending the roles women entrepreneurs act in updating emerging economies and in enabling development of enterprise in economies that are transitioning. This especially is increasingly significant (OECD, 2014a). This is principally severe as social structures, structured social life, family and work, (Aldrich, 1989) are widely varied in emerging countries (Allen and Truman, 1993). Meanwhile, the theories concerning women entrepreneurs and the roles they play in family businesses have been sourced mainly from research conducted in industrialized countries, it is imperative to scrutinize the degree of application of these theories when taken into context of emerging nations. Turkey as an emerging country is where women pursue self-employment in order to overcome occupational segregation and to contribute to the development of Turkey's transitional economy. Given the small size of the country and its principally sturdy family orientation and women's general education level which echoes societal structures that vary from numerous industrialized countries (Renko et al., 2012). Notwithstanding, the researchers came to the conclusion that a change in the educational setup should be preceded by changes or modernization of the business environment (Radovic-Markovic et al., 2012).

Furthermore, very little has been identified concerning the reasons of starting a business owned by women, or any other entrepreneurial activities functioning inside the two big cities- Izmir and Istanbul-in Turkey. This paper aims to observe businesses owned by women in Izmir and Istanbul, with a specific focus on obstacles and opportunities women face while in transition. Therefore, it focused on carrying out a comprehensive research, which led to face-to-face and cross-sectional survey design being used to report the vision of changes suggested by the respondents. It was found that women entrepreneurs are facing far more opportunities in starting and running a business venture. The study also reveals that women do business in order to generate income and essentially become independent. Yet, businesses owned by women make a crucial contribution to the incomes of households as well as the growth of the economy.

Women Entrepreneurship in Turkey

Turkey as a country in Eurasia has experienced quite a few significant alterations in a small frame of time. From the sixteenth century, during the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, numerous attempts were made to present dynamic changes to the old-fashioned Turkish society (Wasti, 1998), of which its priorities were patriarchal values and religiousness. The examination of women in the society exposed the concurrent impact of Western and Eastern cultures in a Turkish context (Kabasakal et al., 2011). Turkish women at that time were equal to men in regards to their status in society from the time the Turks’ appeared in Middle Asia until around the eighth century.

With Islam's diffusion among Turks, women started to lose their social status because of the influence of Iranian and Arabic cultural norms on the culture of Turkey (Karataş-Özkan et al., 2011). Nonetheless, in the second part of the nineteenth century, women began to get back their social status. Atatürk, who was the pioneer of the modern Turkish Republic, led the modern movement and enhanced women’s status in the Turkish community (Aycan, 2004). In the 1930s, Turkish women got the right to vote while in specific European countries, they attained this right in the 1940s. Regardless of these developments, women in Turkey still have to deal with specific issues, which cropped from the duality between patriarchal and religious Middle Eastern Values on one hand and secularism on the other. (Kabasakal et al., 2011).

Past research has proven that Turkish women entrepreneurs are generally more than 30 years of age (Hisrich and Özturk, 1999; Ufuk and Özgen, 2001a, 2001b; Özar, 2007; Yılmaz et al., 2012). This is close to women entrepreneurs in diverse countries in past studies. When women get to their thirties, their gender responsibility in the home is almost over because their kids are almost grown up (Ince, 2012). The research has also shown that most of the women entrepreneurs in Turkey are married although the married entrepreneur percentage is quite more among men.

As regards women entrepreneur’s level of education, past research has shown results, which were consistent. Pulling from the GEM data attained from adults in Turkey who were 2,417 in number in 2006, Çetindamar et al. (2012) observed that asides from graduate education, women who got an elevated level of education have a higher possibility of engaging in entrepreneurship in comparison to men. The authors state the powerful impact of education on women's entrepreneurship using the glass ceiling effect (Masser and Abrams, 2005) and recommend that women with a more enhanced human capital have a higher tendency of engaging in entrepreneurial activities in countries like Turkey, which are developing. This is because of the limited chances given to them in the traditional place of work. Similarly, using a sample in Tekirdag, Turkey, Yılmaz et al. (2012) observed that a huge part of women entrepreneurs in Tekirdag either have a high school education level or higher education level. These findings tally with initial facts by Özar (2007) and Ufuk and Özgen (2001b), which state that entrepreneurs in Turkey who are women are generally properly educated.

With respect to the past work statures of Turkish women entrepreneurs, mixed results have been provided by previous studies. Özar (2007) states that during the period 80% of the men entrepreneurs were working in an office before beginning their businesses, for women, this ratio reduces to 53%. 24% of women who took part in the study case of Ozar stated that before they decided to become entrepreneurs, they were housewives. In another aspect, in Ufuk and Özgen’s (2001a, b) study, 61% of women entrepreneurs stated that they were working already before they became entrepreneurs.

It has also been shown by research that enterprises owned and built by women in Turkey are shared across these two geographical locations come in different assets and sizes. There are various reasons why there are only few women performing optimally in entrepreneurship and these reasons affect the female enthusiasm in toeing the line of entrepreneurship (Ojo et al., 2015). Turkish women in almost all sectors have managed enterprises. Some of which consist of Information technology, international trade, manufacturing, and advertising (Cindoğlu, 2003); nonetheless, the ratio of male entrepreneurs that took part in the manufacturing of technology surpasses that of women entrepreneurs (Çetindamar, 2005).

Motivations to women entrepreneurs

The world is now a global village and this globalization has kicked started the spread of business activities and collaborations beyond the shores of one’s country of origin (Aspelund et al., 2017).

Therefore, women need to be moulded into entrepreneurs who can easily identify an idea and grow it into a business. Every business idea comes with its opportunities as well as threats to its implementation making it hard for one to just say it’s a good idea through intuition. Factors such as the availability of market for the product and services to be offered, labor, raw materials for the products, local government policies in the designated area among many others factors that affect business development (Hisrich et al., 2017). Therefore, one making a decision to invest on a particular venture based on his/her guts is the first step to failure of the business. Furthermore, sentimental statements in business tend to reflect lack of confidence in handling the issue at hand and one opting to guess or gamble without relevant information.

Entrepreneurs are open-minded individuals who do not use guts but informed decisions to find viable business ideas and invest in them. First, they identify the gaps in the market to look into which services or products are not offered in the areas they want to invest. Once they recognize the gap, they can decide to fill the gap or offer similar services or products. The later however, comes with additional improvements that will make the clients leave their usual producers and choose the new product or service. The improved line of production by the entrepreneur makes it favourable for the consumers to amass more clients (Casson, 2010).

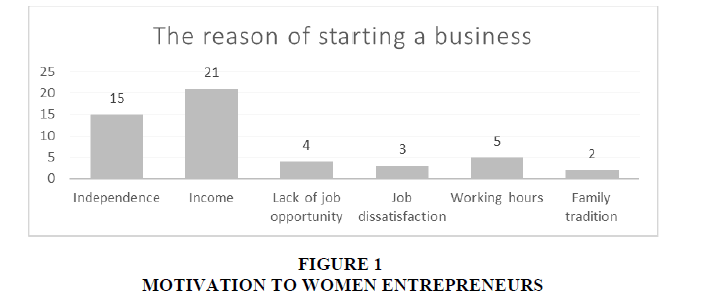

Women can learn a skill through empowerment and academic growth. Other entrepreneurship issues that women can learn in these programs are commitment and critical analysis. One must be enthusiastic in managing the business since it will require time and efforts to succeed in a very competitive market. Before an entrepreneur decides the business is viable, he or she looks into the profit ratio to determine the market and how capable of making high profits from low investment. The presence of market and insight into how existing businesses operate and make one decide whether the business idea is viable or not. The figure below reveals that female entrepreneurs in urban centres go into new business ventures because they want to make money. A clear majority of them say starting up a business is a move to gaining financial independence, and as such, the motivation for women in urban cities is due to lack of income and financial independence. Female entrepreneurship can be due to either opportunity (Pull factor) or necessity (Push factor) (Figure 1).

A study carried out by Allen and his colleagues in 2002 showed that women from developing countries are motivated into entrepreneurship due to necessity rather than an opportunity. It was revealed in the literature that female entrepreneurs are motivated by necessity in comparison to their male counterpart (Buttner and Moore; 1997; Giacomin et al., 2011; Kariv, 2013 and Zwan et al., 2016). There is a steady rise in female leaders around the world, and this could lead to female entrepreneurs becoming as successful as their male counterparts. That said, for women to continue to grow in the business circles, female leaders have to comprehend fully their challenges and make important choices as regards their choice of management style, which will be beneficial to them all (Radovic-Markovic et al., 2013). Like mentioned earlier, when a comparison is carried out between female entrepreneurs in develop and developing countries, studies reveal that female entrepreneur in developing countries are motivated by necessity or push factors than opportunity or pull factors.

Research Methods And Methodology

This study was carried out in only two cities in the Marmara and Aegen region of Turkey due to the subcultural differences. The choice of these cities was also influenced by the researcher’s familiarity with their culture. The primary goal of the study is to:

1. Look at the family-work conflict women in Izmir and Istanbul face.

2. Investigate the reasons why women start businesses in this region.

3. Look at the problem Turkish female entrepreneurs’ face during the start-up face of their companies.

4. Moreover, finally, to present a profile of the average Turkish woman in Istanbul and Izmir.

To carry out this research efficiently, the relevant local government agency responsible for women entrepreneur development, organizations, unions and women entrepreneurial associations were investigated to get the necessary information about women entrepreneurs in the country. The study aims to improve the standard female entrepreneurs in Turkey, thereby developing successful female entrepreneurs. The study focused on carrying out a comprehensive research rather than having a large pool of data, to do justice to the object of the study, this led to face-to-face and cross-sectional survey design being used. Questionnaires were employed to gather information as it relates to the issues surrounding the study. These questionnaires were shared amongst 50 respondents located in two big cities, Izmir and Istanbul. The number of female entrepreneur resident in the city influenced the choice of cities. Basic data about to age, family size, years of entrepreneurial experience, level of education, number of employees, reasons for entrepreneurship were amongst the information collected via face-to-face survey questionnaire.

Three aspects of family-work conflict (their roles as parents, wives, and homemakers) were measured with the help of a Likert Scale. Open-ended questions were used to measure reasons for starting up a business, and factors responsible for success. In these situations, the respondents were asked to give their top three answers. Due to the cultural, political, social, economic and technical differences between the developed country and a developing country like Turkey, there is a high probability that some of the findings may not work for the Turkish female entrepreneur. For instance, research in developed countries reveals that most family-work conflict is cantered on the support, which is received from one’s partner about childcare and other basic household activities. On the other hand, in developing countries like Turkey, women tend to get funds to pay household help and a higher level of family support. Also, women tend to have other roles to perform (like sister, daughter, and in-law) which are also very timeconsuming.

Despite the fact that this research was carefully organized and prepared, the author is fully aware of its shortcomings and limitations. To start with, the findings recorded herein are limited in its scope as a result of the nature of the study, which is exploratory and not causal. Also, the sample population size is rather small; as only fifty women agreed to take part in the exercise. Finally, data gathered was from Turkey alone.

Reliability and Validity Tests Conducted

Taking a cue from Ormord and Leedy (2010), a quantitative research should always deliver accurate results, which are the outcome of a comprehensive and effective process of data gathering. This can be achieved by making sure the data measuring tools used in the research are reliable and effective. An initial research was carried out to examine the contents of our questionnaire. This initial questionnaire was distributed to fifty entrepreneurs to ascertain its validity. Changes were made to the questionnaires based on the feedback gotten from the entrepreneurs. Alternatively, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient method was used to determine the reliability of the results. The benchmark for reliability was set at 0.7 with anything above that deemed to be reliable. The results were highly reliable with figures ranging from 0.73 to 0.88. The results are displayed in the Table 1 shown below.

| Table 1 RELIABILITY TEST RESULTS |

|

| Statements | A.V. |

| Educational level | 0.88 |

| Business connections | 0.79 |

| Source of funds | 0.85 |

| Family-work conflict | 0.84 |

| Legal and regulatory constraints | 0.77 |

| Marketing/Sales Skills | 0.81 |

| Managing Employees | 0.73 |

| Risk taking propensity | 0.76 |

| Subjective norms | 0.83 |

George and Mallery (2016) put forward the following guidelines for examining alpha value: >0.90 excellent, >0.80 good, >0.70 acceptable, >0.60 questionable, >0.5 poor, <0.5 unacceptable. From the table above it can be deducted that the scales used in this research were reliable and therefore acceptable.

Results And Discussion

Table 2 below shows that a large majority (about 67%) of female entrepreneur's surveyed ran their businesses as private limited companies, which were fully owned by them. While 33% of these businesses were partnerships involving family or spouses. A significant percentage (about 78%) of women surveyed was below the age of 45 years. More than 70% of the women sampled have been married for ten years and more, with about 69% of the women owning a university degree. A large majority of these women were into garment manufacturing, sales of souvenir products, handicrafts, supply of food items or design.

| Table 2 CHARACTERISTICS OF WOMEN ENTREPRENEURS |

|||

| Number | Percentage | ||

| Type of Business | Manufacturing | 26 | 57 |

| Retailer | 4 | 8 | |

| Wholesaler | 9 | 15 | |

| Service | 8 | 13 | |

| Other | 3 | 7 | |

| Educational Level | Literate/ Read and Write | 2 | 1 |

| Primary | 4 | 5 | |

| Secondary | 7 | 11 | |

| Technical/Vocational | 9 | 14 | |

| University Level or above | 28 | 69 | |

| Ownership | 100% Self | 34 | 67 |

| Partnership | 16 | 33 | |

| Number of Employees | 5 or under | 26 | 48 |

| 06-Oct | 7 | 16 | |

| Nov-20 | 10 | 21 | |

| 21-30 | 5 | 11 | |

| 31+ | 2 | 4 | |

| Age | 21-25 | 6 | 12 |

| 26-34 | 12 | 25 | |

| 35-44 | 21 | 41 | |

| 45-54 | 9 | 17 | |

| 55+ | 2 | 5 | |

| Year of Marriage | Single | 1 | 2 |

| 5 or under | 4 | 5 | |

| 06-Oct | 12 | 16 | |

| Nov-20 | 31 | 73 | |

| 20+ | 2 | 4 | |

| Source of Funds | Self | 27 | 51 |

| Family | 4 | 7 | |

| Banks | 14 | 34 | |

| Other | 5 | 8 | |

| Business Connections | Parent in business | 10 | 21 |

| Spouse in business | 23 | 43 | |

| Other family | 5 | 14 | |

| None | 12 | 22 | |

It is important to point out that more than 60% of respondents had a spouse or a parent who was into entrepreneurship. These results are a lot similar to results obtained from other countries. However, there are some obvious differences. For example, the respondents interviewed in this research had minimal prior work experience and many of them had families with business contacts. The number of married women was also significantly higher than what was obtainable in other countries. For example, several studies in other countries indicate that women entrepreneurs are less likely to be married (Buttner and Moore, 1997; Verheul and Thurik, 2001; Wellington, 2006; Sciascia et al., 2012; Raknerud and Rønsen, 2014; Shmailan, 2016) than their male counterparts. In addition, the number of women operating manufacturing firms is higher than found in most western Studies (Buttner and Moore, 1997; Eastwood, 2004; Cesaroni and Sentuti, 2016).

Challenges Faced by Women Entrepreneurs

The main challenge female entrepreneurs face when starting a business are cash flow issues. Other includes phrases that were frequently mentioned were: “inadequate capital”, “inadequate managerial experience” and “lack of time”. Table 3 reveals that the main source of capital to set up their business were from personal savings or money borrowed from family/spouse to set up the business and as such, problems like inadequate working capital are bound to surface. 41% had obtained loans from financial institutions, but a large chunk of this loan just served as a part of their initial investment and not their primary source of funding.

| Table 3 THE PROBLEMS IN START-UP AND CURRENT |

||

| Problems | Start-up | Current |

| Cash flow | 21 | 17 |

| Inadequate Capital | 5 | 4 |

| Managing Employees | 9 | 9 |

| Marketing/Sales Skills Required | 12 | 9 |

| Inadequate Managerial exp. | 8 | 5 |

| Inadequate of Time | 7 | 6 |

| Family Challenges | 3 | 5 |

| Legal and regulatory constraints | 3 | 4 |

| The legal or regulatory system | 4 | 4 |

| Insufficient Business training | 4 | 3 |

| Lack of adequate infrastructure | 3 | 4 |

| Tax levy | 3 | 4 |

A sizeable percentage (about 72%) of these women had no prior experience in running a business. This usually accounted for the several problems and challenges being encountered by these women. When questioned further about what their pressing challenge was, they frequently responded with “cash flow,” which was accompanied by employee management and marketing challenges. Legal and regulatory limitations female entrepreneurs faced also presented another set of challenge to female entrepreneurs. This result is consistent with previous studies carried out in this area. In 1993, Allen and Trumen revealed that government regulations and legal limitations in developing countries was one of the challenges facing women in entrepreneurship. While GEM revealed in 2017 that in addition to government regulations, bureaucracies and corruption were also factors limiting the success of female entrepreneurs. The tax levy charged to female entrepreneurs was not in line with the business they ran. These financial limitations have been repeated by different independent studies on female entrepreneurship. Ufuk and Ozgen in 2001; Sidło et al., 2017; Holloway et al., 2017 came to the same conclusion that financial problems are prevalent in female startups and in expanding female businesses. Brush and Hisrich (1984) also revealed prevalent financial limitations female entrepreneurs encounter when starting and building on their business.

Family-Work Conflicts

The female entrepreneur believed her business had little or no effect on how she performed her role as a wife, homemaker and a parent. This perspective is evident from Table 4 displayed below. Women encountered minimal levels of family-work conflicts in their marital and parental roles. For instance, the average score for the variables used in assessing their relationship with their spouses was 2.4 this signifies a lower conflict level. The figure for the parental role was 2.6, which is below the midpoint. Amongst the roles assessed, the homemaker role was the role that produced the highest level of conflict with a score of 3.4. It is important to note that all the women interviewed had external help in dealing with their household chores, be it a part-time or a full-time house help. Despite having such help, they still had little time or energy left to take care of their household duties. What could be the reason for this?

| Table 4 FAMILY-WORK CONFLICTS |

|

| Mean | |

| Relationship with Spouse | |

| Enhances relationship | 3.02 |

| Prevents me from sharing quality time | 2.48 |

| Affects my relationship negatively | 1.86 |

| Too exhausted to carry out activates with a spouse | 2.39 |

| Business affects marriage negatively | 1.53 |

| Average | 2.4 |

| Relationship with Children | |

| Makes difficult to have meaningful relations | 1.85 |

| Working hours affect with time spent with children | 2.09 |

| Irritable; better in business than parenting | 1.92 |

| Exhausted from business have little or no time for parenting | 2.18 |

| Enhances parenting skills | 2.42 |

| Average | 2.6 |

| Homemaker Role | |

| Difficulty in performing household chores | 2.51 |

| Spends more time with the business and as such cannot do more at home | 2.43 |

| Affects severely the ability to carry out household chores | 2.11 |

| Too tired to do chores | 2.27 |

| Allows for household chores to be done | 1.62 |

| Average | 3.4 |

A considerable number of women interviewed alluded to the fact that they had tremendous support from their spouses as it relates to their business. They revealed that their spouses were extremely happy with their level of interest in their business and provided them with enough emotional and moral support. So, even though their spouses did not offer much support regarding household chores or babysitting they were more than satisfied with the level of support they got from their partners. This also accounts for why many women interviewed rated partner support as the main reason for their entrepreneurial success. Some also stated that a woman cannot be successful without support from her partner. Another factor that might have contributed to why these women enjoyed tremendous spousal support might be due to the stability of their marriage. Many of these women were in stable, long-lasting marriages with more than 85% of women revealing they were satisfied or more than satisfied with their marital situation. Extended family support is another factor that could be responsible for the low level of family-work conflict being experienced by female entrepreneurs. Many of them revealed that they had supportive in-laws and parents on their side with at least a member of the extended family living with them. This could be responsible for lowering the childcare burden placed on these women. The low conflict levels are reflective of the high satisfaction level, with these women posting average scores like 4.3 for life in general, 4.1 for marriage satisfaction and 3.8 for parental roles. Also, a lot of them were satisfied with the way the business was growing with an average score of 4.1, and over 85% were satisfied with the growth level of the business.

Reasons for Starting a Business

When the female respondents were asked the reason why they ventured into business in the first place, many of the responses received were due to financial reasons. Twelve of them said their motivation was financially inclined; four was to contribute to the family's income or because their husbands were unemployed. Hence, financial reasons seem to be the number one reason why women venture into business. This is quite different from reports in developed countries than developing ones.

About 50% of the respondents of the sample were motivated by the need to for a new challenge, being able to do something entirely on their own and show they are capable of being independent or indicate to whoever is watching that they can succeed in business. There are others who are motivated by their love for a craft, and due to the availability of time on their hands, they proceed to pursue their interest. For these set of female entrepreneurs, business was first a hobby, which then evolved into a thriving business organization.

Final on the list of motivating factors is the will and desire to help others, for example, being able to provide employment to others, serve as the perfect role model for their kids, or just a burning desire to contribute positively to society. These reasons can be categorized as “pull factors” their reasons go beyond themselves and their immediate needs or desire for personal success. Research carried out in other developed countries show that there is a “push” factor involved in their reason for venturing into entrepreneurship, as many of them are not satisfied with their current jobs.

It is important to stress that the push factors here were mainly due to job satisfaction. Unlike in the west, the female entrepreneurs ventured into business were at the height of their childbearing ages. The study also reveals that there is a difference from similar studies carried in other countries, which show that female entrepreneurs were primarily motivated by the desire to achieve more than financial reasons (Rajan and Zingales, 1998; Glancey et al., 1998; Karagiannis, 1999). Being able to balance work and family was not a major reason why these women ventured into entrepreneurship. Only one out of the women interviewed mentioned that time flexibility was one of the reasons why she decided to go into entrepreneurship (Table 5).

| Table 5 REASONS FOR STARTING A BUSINESS |

||

| Number | Percentage | |

| Idle time/needed to be occupied | 12 | 17 |

| Hobby/special interest/passion | 8 | 13 |

| Money | 13 | 18 |

| Financial needs/alternate source of income for the family | 7 | 9 |

| Family business | 5 | 7 |

| Independence over time | 3 | 4 |

| Self-motivating challenge | 11 | 15 |

| others independence | - | - |

| Self-worth/Satisfaction | 7 | 10 |

| A role model to children | 3 | 4 |

| Job creation | 2 | 3 |

Conclusion

Women, as entrepreneurs are still being under-represented. When asked, fewer women than men state that they would rather be self-employed. When they do make the choice of becoming entrepreneurs, they state a more balanced work-life more times than men as their main encouragement for beginning a business. As they regularly split their time between caring and working, the business responsibilities of women are often in a limited sector range and on a smaller scale. They often possess minimal experience when they begin a business and have a less likelihood than men to loan cash to fund their business. Yet, businesses owned by women make a crucial contribution to the incomes of households as well as the growth of the economy.

In the lens of analysis, female entrepreneurs are growing rapidly; this has led to a serious interest in this topic. This research analysed the challenges being faced by women in two urban cities in Turkey in starting and running a business venture, the reasons behind their drive to be an entrepreneur and the challenges posed because of the family-work conflicts they faced. While they have been several types of research carried out on female entrepreneurs, very few of those researches have focused on women in developing countries like Turkey. This study reveals that female entrepreneurs in developed and developing countries currently have some similarities and differences in their experience. For instance, the study revealed that initial start-up challenges faced by both women are similar.

Female entrepreneurs are driven by necessity factors (push factors). The study reveals that women do business in order to generate income and essentially become independent. This revelation was supported by former studies. Female entrepreneurs in developing countries usually begin their business due to necessity more than opportunity. To throw more light on this, female entrepreneurs usually begin their business using their personal savings and income generated from family and friends. In summary female entrepreneurs in these two cities, begin their businesses on their own.

The finance is a major limiting factor to female entrepreneurs. Women find it very difficult to obtain loans to start or grow a business. Add that to the fact that a female entrepreneur usually does not have access to services offered by microfinance and other money lending financial institution. They also require training and programs on how to improve their business. The government and their bureaucratic set up are not left out, as they also pose a challenge to female entrepreneurs. Female entrepreneurs in the cities sampled tend to pay more in taxes, which are not commiserated with their business. While there are also no legal framework that provide a suitable environment for female entrepreneurs to succeed in these cities.

Finally, on the list, lower levels of family-work conflicts in this study reveals that female entrepreneurs usually have a strong family support system and they had cost-effective house help on hand to assist. Other considerations should be given to the difference in economies. For example, the Turkish government has several programs in place that supports female entrepreneurs; this can be directly responsible for the number of women who made use of outside funding to start up their business. It is important to emphasize that this study is primarily exploratory and as such the results are specific to female entrepreneurs in just two urban cities in Turkey and the results may offer clarity for other studies and serve as a guide for further research.

Scientific Implications

The number of female entrepreneurs is continually on the rise, and they are creating a diverse market that drives economic growth. There is a need for further research on this topic, as the studies that have been carried out tend to compare female entrepreneurs with the male entrepreneurs. There is a need to compare women with themselves to know how to encourage more female entrepreneurs.

This comparison is necessitated by the fact that the differences between men and women, as their distinctive styles of management, or the fact that men tend to last longer as entrepreneurs than women are. There are also cultural issues that either discourages or encourages female entrepreneurs, and this needs to be addressed as culture differs from one society to another amongst developed or developing countries of the world.

References

- Aldrich, H. (1989). Networking among women entrepreneurs. In O. Hagan, C. Rivchum & D.L. Sexton (Eds.),Women-owned businesses (pp. 103-132). New York: Praeger.

- Allen, S., & Truman, C. (Eds.). (1993). Women in business: Perspectives on women entre- preneurs. London: Routledge Press.

- Aspelund, A., Fjell, L., & RÝdland, S.E. (2017). Doing Good and Doing Well? International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 21(2), 13-32.

- Aycan, Z. (2004). Key success factors for women in management in Turkey. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 53(3), 453-477.

- Brush, C.G., & Hisrich, R.D. (1991). Antecedent influences on women-owned businesses. Journal of Management Psychology, 6(2), 9-16.

- Buttner, E.H., & Moore, D.P. (1997). Women Entrepreneurs: Moving Beyond the Glass Ceiling. Sage Publications.Thousand Oaks: USA.

- Casson, M. (2010). Entrepreneurship. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Cesaroni,F.M., & Sentuti, A. (2016). She is the founder, Who is the emotional leader? Proceedings of the 11th European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship-ECIE 2016, 15-16 September 2016, Jyvaskyla, Finland.

- «etindamar, D. (2005). Policy issues for Turkish entrepreneurs. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 5(4), 187-205.

- Cetindamar, D., Gupta, V.K., Karadeniz, E.E., & Egrican, N. (2012). What the numbers tell: The impact of human, family and nancial capital on women and men?s entry into entrepreneurship in Turkey?. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development: An International Journal, 24(2), 29-51.

- Cindoglu, D. (2003). Bridging the gender gap in Turkey: A milestone towards faster socio-economic development and poverty reduction. Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Unit, Europe and Central Asia Region, OECD.

- Eastwood, T. (2004). Women Entrepreneurs: Issues and Barriers: A Regional, National and International Perspectiv. St Albans: Exemplas Ltd.

- Gardner, J.C., McGowan, C.B., & Sissoko, M. (2014). Entrepreneurship and Economic Freedom. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 18(1), 101-113.

- GEM (2001). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Executive Report. GEM, London. GEM (2012). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2012 Report. GEM, London.

- Giacomin, O., Janssen. F., Guyot, J.I., & Lohest, O. (2011). Opportunity and/or necessity entrepreneurship? The impact of the socio-economic characteristics of entrepreneurs, MPRA Paper No. 29506.

- Glancey, K., Greig, M., & Pettigrew, M. (1998). Entrepreneurial dynamics in the small business service sector. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 4(3), 249?68.

- Gupta, V.K., Turban, D.B., Wasti, S.A., & Sikdar, A. (2009). The role of gender stereotypes in perceptions of entrepreneurs and intentions to become an entrepreneur. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(2), 397- 417.

- Gupta, S.L., & Ranian, R. (2009). Factor Analysis of Impediments for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises in Bihar. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 20(1), 74-83.

- Hisrich, R.D., & ÷zturk, S.A. (1999). Women entrepreneurs in a developing economy. Journal of Management Development, 18(2), 114-125.

- Hisrich, R.D., Peters, M.P., & Shepherd, D.A. (2017). Entrepreneurship. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Holloway, K., Niazi, Z. & Rouse, R. (2017). Women?s economic empowerment through financial inclusion: A review of existing evidence and remaining knowledge gaps. Financial Inclusive Program: Innovations for Poverty Sction: Washington, D.C.

- Javadian, G., & Singh, R.P. (2012). Examining successful Iranian women entrepreneurs: an exploratory study.Gender in Management: An International Journal, 27(3), 148-164.

- Ince, M. (2012). Obstacles and future prospects of women entrepreneurs: The Turkish context. Economia Marche Journal of Applied Economics, 31(2), 61-73.

- Kabasakal, H., Aycan, Z., Karakas, F., & Maden, C. (2011). Women in management in Turkey. In Davidson, M.J. & Burke, R. (Eds), Women in Management Worldwide: Progress and Prospects (pp. 317-338). Gower Publishing Limited, Surrey.

- Karagiannis, A.D. (1999). Entrepreneurship and the Economy, Interbooks: Athens.

- Karata?-÷zkan, M., ?nal, G., & ÷zbilgin, M. (2010). Turkey. In Fielden, S. & Davidson, M. (Eds), International Handbook of Successful Women Entrepreneurs, (pp. 175-188.). Edward Elgar Press, Cheltenham and New York, NY.

- Karata?-÷zkan, M., Erdogan, A., & Nicolopoulou, K. (2011). Women in Turkish family businesses: Drivers, contributions and challenges. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 11(2), 203-219.

- Kariv, D. (2013). Female Entrepreneurship and the New Venture Creation: An International Overview. Routledge: UK.

- Leedy, P.D., & Ormrod, J.E. (2010). Practical research: Planning and design (9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Masser, B.M., & Abrams, D. (2005). Reinforcing the glass ceiling: The consequences of hostile sexism for female managerial candidates. Sex Roles, 51(9-10), 609-615.

- Minniti, M., & Naudť, W. (2010). What do we know about the patterns and determinants of female entrepreneurship across countries? European Journal of Development Research, 22(3), 277-293.

- Ojo, E.D., Anitsal, I., & Anitsal, M.M. (2015). Poverty among Nigerian Women Entrepreneurs: A Call for Diversification of Sustainable Livelihood in Agricultural Entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 19(1), 167-179.

- ÷zar, S. (2007). Women entrepreneurs in Turkey: Obstacles, potentials and future prospects.

- Phipps, S.T.A., Prieto, L.C., & Kungu, K.K. (2015). Exploring the Influence of Creativity and Political Skill on Entrepreneurial Intentions among Men and Women: A Comparison between Kenya and the USA. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 19(1), 179-194.

- Radovic-Markovic, M., Lindgren, C.E., Grozdani?, R., Markovic, D., & Salamzadeh, A. (2012). Freedom, individuality and women`s entrepreneurship education. International Conference-Entrepreneurship education - a priority for the higher education institutions, 8-9 October, Romania.

- Radovic-Markovic, M., Salamzadeh, A., & Razavi, S.M. (2013). Women in Business and Leadership: Critiques and Discussions. The 2nd Annual International Conference on Employment, Education and Entrepreneurship, Belgrade, Serbia.

- Radovic-Markovic, M., Salamzadeh, A., & Kawamorita, H. (2016). Barriers to the advancement of women into leadership positions: A Cross National Study. International Scientific Conference on Leadership and Organization Development, (pp. 287-294). Kiten, Bulgaria.

- Rajan, R.G., & Zingales, L. (1998). Financial dependence and growth. American Economic Review, 88(3), 559-586. Raknerud, A., & RÝnsen, M. (2016). Why are there so few female entrepreneurs? An examination of gender differences in entrepreneurship using Norwegian registry data. Discussion Paper: Statistics Norway Research department (pp. 1-36).

- Renko, M., El Tarabishy, A., Carsrud, A., & Bršnnback, M. (2012). Entrepreneurial leadership in the family business. In A. Carsrud & M. Bršnnback (Eds.), Understanding family business: undiscovered approaches, unique perspectives and neglected topics (pp. 169-184). Heidelberg: Springer.

- Sciascia, S, Mazzola, P, Astrachan, J.H., & Pieper, T.M. (2012). The role of family ownership in international entrepreneurship: Exploring nonlinear effects. Small Business Economics, 38(1), 15-31.

- Shmailan, A.B. (2016). Compare the Characteristics of Male and Female Entrepreneurs as Explorative Study. Journal of Entrepreneurship & Organization Management, 5(4), 1-7.

- Sid?o,K., Frizis, I., Dragouni, O., Ruzik-Sierdzi?ska, A., Gigitashvili, G., Beaumont, K., & Hartwell, C.A. (2017). Women?s Empowerment in the Mediterranean Region. CASE (Center for Social and Economic Research), Warsaw, Poland.

- Ufuk, H., & ÷zgen, O. (2001b). The profile of women entrepreneurs: a sample from Turkey. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 25(4), 299-308.

- Ufuk, H., & ÷zgen, O. (2001a). Interaction between the business and family lives of women entrepreneurs in Turkey. Journal of Business Ethics, 31(2), 95-106.

- Turkish Statistical Institute (TUIK) (2017). Labor force statistics dynamic search-2017.

- Van der Zwan, P., Thurik, R., Verheul, I., & Hessels, J. (2016). Factors influencing the entrepreneurial engagement of opportunity and necessity entrepreneurs. Eurasian Business Review, 6(3), 273-295.

- Verheul, I.A., & Thurik, R. (2001). Start-up capital: Differences between male and female entrepreneurs; Does gender matter? Small Business Economics, 16(4), 329-346.

- Vossenberg, S. (2013). Women entrepreneurship promotion in developing countries: what explains the gender gap in entrepreneurship and how to close it? Working Paper No. 2013/08, Maastricht School of Management, March 2013, Maastricht.

- Wellington, A.J. (2006). Self-employment: the new solution for balancing family and career? Labour Economics, 13, 357-386.

- Welter, F., Smallbone, D., Mirzakhalikova, D., Schakirova, N., & Maksudova, C. (2006). Women entrepreneurs between tradition and modernity-the case of Uzbekistan. In Welter, F., Smallbone, D. & Isakova, N. (Eds), Enterprising Women in Transition Economies ( pp. 45-66). Ashgate, Hampshire.

- Wasti, S.A. (1998). Cultural barriers in the transferability of Japanese and American human resources practices to developing countries: the Turkish case. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 9(4), 608-631.

- Y?lmaz, E., ÷zdemir, G. & Oraman, Y. (2012). Women entrepreneurs: Their problems and entrepreneurial ideas. African Journal of Business Management, 6(26), 7896-7904.