Research Article: 2020 Vol: 24 Issue: 1

An Empirical Study of the Dimensions of Entrepreneurial Marketing

Dhananjay Bapat, Indian Institute of Management, Raipur

Abstract

Entrepreneurial Marketing (EM) would help organisations remain relevant and competitive in the world full of uncertainties brought about by advances in science and technology on the one hand and shrinking product and business life cycles on the other. EM has been evolving over the last three decades, But there has not been a consensus on the definition of EM. A few of these definitions have suggested the dimensions of EM. The empirical investigations have not confirmed the dimensions of these EM definitions. The purpose of this study is to empirically verify the six dimensions of EM as proposed by Kilenthong, Hills and Hultman in the Indian context. Structural Equations Modelling was used to analyse. Results showed that five factors fit well in the model.

Keywords

Entrepreneurial marketing, India, Entrepreneurial marketing dimensions

Introduction

The advances in knowledge, science, and technology have helped organisations come out with better solutions for customers at faster rates. It has also helped the customers by proliferating information to become more knowledgeable about the options and alternatives available to them and hence more demanding. While product life cycles and business life cycles are reducing, organizations have to operate in conditions where changes are dynamic, entry barriers are reducing, competition is increasing (including solutions from other industries), ability to forecast medium to large term becoming more difficult, shareholder pressures are increasing (and with many having short term objectives). As a result, the organisations would have to become even more proactive, innovative, and agile than ever before in highly uncertain market conditions, and entrepreneurial marketing (EM) could help organisations remain relevant and competitive (Alqahtani & Uslay, 2018).

While there is an agreement that there is a difference between traditional marketing and EM (Hills et al., 2008), a consensus on the definition of EM is yet to see the light of the day. The EM concept “has been used in various ways, and often somewhat loosely” (Morris et al., 2002). In the initial stages, EM was linked to the marketing efforts of small organisations/ small and medium enterprises (SMEs) (Hill & Wright, 2000) and by some to resource-constrained organisations (Morris et al., 2002); the scope has increased subsequently (Hills & Hultman, 2013). While some looked at EM from the lens of marketing for new and/ or small ventures, others looked at EM from a qualitative perspective of marketing with an entrepreneurial perspective (Miles & Darroch, 2006). Though entrepreneurial Marketing has evolved as a field in the last 30 years (Collinson & Shaw, 2001), it is still under development (Hills & Hultman, 2011). EM is as applicable to organisations of considerable size (Lam & Harker, 2015) or for that matter to any size (Kraus et al., 2010) and in either B2C or B2B contexts (Whalen et al., 2016; Yang & Gabrielsson, 2017).

Some of the definitions of EM suggested the dimensions of entrepreneurial marketing (Morris et al., 2002; Jones & Rowley, 2009; Mort et al., 2012; Kilenthong et al., 2015). Based on each definition, EM has different dimensions associated with it. Most of the EM models are theoretical constructs, and some researchers have tried verifying them in select countries, in specific conditions.

The Jones & Rowley framework (2009) was built on the SME context, and the Mort et al. framework (2012) was built in the context of born global firms. The Kilenthong, Hills and Hultman framework was universal and built on the model proposed in 2006 by Hills and Hultman. Earlier research treated entrepreneurial orientation (EO) as a dimension of EM. Based on their findings, Kilenthong et al. suggested that rather than looking at EO as a dimension, it should be considered as a separate construct that is an antecedent of EM behaviour (Kilenthong et al., 2015).

The literature showed that Kilenthong, Hills and Hultman model requires to be tested by using a quantitative method. The purpose of this research is to validate the entrepreneurial dimensions proposed by Kilenthong, Hills and Hultman (Kilenthong et al., 2015) in the Indian context (where these studies have not yet been done).

Entrepreneurial Marketing Definitions And Dimensions

Though there have been significant advances in the area of entrepreneurial marketing, there has not been a consensus on what are the dimensions of EM, the drivers, and the measurement included. The drivers vary because there is no one clear definition of EM. Some of the popular definitions and dimensions are described below.

One of the pioneering definitions of Entrepreneurial marketing is

“The proactive identification and exploitation of opportunities for acquiring and retaining profitable customers through innovative approaches to risk management, resource leveraging and value creation” (Morris et al., 2002).

Based on this definition, seven dimensions of EM were identified as proactive orientation, opportunity focus, customer intensity, innovativeness, calculated risk-taking, resource leveraging, and value creation.

In 2009, a framework with fifteen dimensions of EM was developed (Jones & Rowley, 2009). These were derived from the SME levels of entrepreneurial orientation (EO), market orientation (MO), innovation orientation (IO), and customer orientation (CO). This is referred to as the EMICO framework.

Based on a study of Australian firms, (Mort et al., 2012) identified four dimensions. The four dimensions were opportunity creation, customer intimacy based innovative product, resource enhancement and legitimacy.

In 2018, researchers suggested that for organisations that are operating in highly competitive and uncertain environments, EM would be the key to help them “remain relevant, competitive and healthy” (Alqahtani & Uslay, 2018). Based upon their study of various EM perspectives, service-dominant logic, and the effectuation theory, they proposed a model of EM which had eight dimensions. The eight dimensions proposed by them are innovation, proactiveness, value co-creation, opportunity focus, resource leveraging, networking, acceptable risks, and inclusive attention.

Though there is no single definition of EM, most are based on the definition proposed by (Morris et al., 2002). Although scholars have researched EM, there is no consensus on the dimensions of EM (Kilenthong et al., 2015).

There have been concerns raised that the premises of EM have not been “empirically tested and replicated to test for generalizability” (Eggers et al., 2018).

Researchers tried to empirically test the seven dimensions based on the definition proposed by Morris et al. (Kocak, 2005; Schmid, 2012; Fiore et al., 2013). While Kocak researched small organisations, Schmid researched small and medium enterprises. Kocak’s research was conducted in Turkey, and instead of the seven dimensions, the study confirmed five. Schmid's research was in Austria and could confirm only four dimensions. Fiore et al. has studied US organisations and could confirm only four.

Based on a review of published empirical research papers, it was suggested that EM had six dimensions (Kilenthong et al., 2015). The six dimensions were “Growth orientation, opportunity orientation, total customer focus, value creation through networks, informal market analysis, and closeness to the market.”

This study builds on previous studies of entrepreneurial marketing and applies in the Indian context.

Survey Development

The objective of this study was to investigate the six dimensions model of EM (Kilenthong et al., 2015) in the Indian context. The study used the primary source of data collection. This was achieved by the design and administration of a targeted survey to entrepreneurs in India. A formal questionnaire developed by Kilenthong et al. (2015) was used for the structured data collection. Widely used and accepted scales were used in the questionnaire. The survey items included a range of questions to gather necessary information about the entrepreneur. It also captured information about the enterprise. Structured, personal in-home interviews were conducted using survey questionnaires so that the respondents were interviewed face to face in their home/ office.

Most questions had fixed alternative questions that would require the respondent to select from a predetermined set of responses. Most of the measures in the questionnaire were self-reported perceptual measures of the constructs. The itemised rating scale, a Likert scale (non-comparative scale/ metric scale), was used. The respondents had to indicate the degree of agreement or disagreement with each of the series of statements. A five-point Likert scale was used.

The target population of this study was the Indian owner/ founder/ partner/ major shareholder of the organisations (referred to as the business owners) that have been in existence for a different number of years. The precondition or eligibility of the survey was that the enterprise should be in operation for a year.

The data was collected using the questionnaire by the researcher directly in the financial year 2018-19. Only completely filled questionnaires were used for the analysis. Partially filled questionnaires were discarded. As the business owners were hard-pressed for time, if needed, multiple visits were made to get the fully filled questionnaires. The survey responses were coded and entered into the computer. The six dimensions and measures are shown in Table 1.

| Table 1: Entrepreneurial Marketing Dimensions And Its Measures | ||

| Dimensions of EM | Measures | |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Orientation | A1 | Long term growth is more important than immediate profit. |

| A2 | Our primary objective is to grow the business. | |

| A3 | We try to expand our present customer base aggressively. | |

| Opportunity orientation | B1 | We constantly look for new business opportunities. |

| B2 | Our marketing efforts lead customers rather than respond to them. | |

| B3 | Adding innovative products/ services is important to our success. | |

| B4 | Creativity stimulates good marketing decisions. | |

| Total customer focus | C1 | Most of our marketing decisions are based on what we learn from day to day customer contact. |

| C2 | Our customers require us to be very flexible and adapt to their special requirements. | |

| C3 | Everyone in this firm makes customers a top priority. | |

| C4 | We adjust quickly to meet changing customer expectations. | |

| Value creation through networks | D1 | We learn from our competitors. |

| D2 | We use our key industry friends and partners extensively to help us develop and market our products and services. | |

| D3 | Most of our marketing decisions are based on exchanging information with those in our personal and professional networks. | |

| Informal Market Analysis | E1 | Introducing new products/ services usually involves little formal market research and analysis. |

| E2 | Our marketing decisions are based more on informal customer feedback than on formal market research. | |

| E3 | It is important to rely on gut feeling when making marketing decisions. | |

| Closeness to market | F1 | Customer demand is usually the reason we introduce a new product and/ or service. |

| F2 | We usually introduce new products and services based on the recommendations of our suppliers. | |

| F3 | We rely heavily on experience when making marketing decisions. | |

Structured equation modelling was used to analyse the findings.

Sample Characteristics

Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of business owners.

| Table 2: Demographic Characteristics | |||

| Age | % | Gender | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Below 24 | 3.8 | Male | 77.47 |

| 25 to 29 | 13.2 | Female | 22.53 |

| 30 to 39 | 40.1 | ||

| 40 to 49 | 34.1 | ||

| 50 and above | 8.8 | ||

Seventy-seven per cent of the respondents were male. Of the total sample, 17 per cent were less than 30 years of age, 40 per cent were between 30 to 39, and 34 per cent were between 40 to 49 years of age.

| Table 3: Business Characteristics | |||||

| Type of Enterprise | % | Sector | % | Annual Sales turnover (in INR Million) | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proprietorship | 41.76 | Manufacturing | 29.1 | Up to 50 | 69.8 |

| Partnership | 3.85 | Service | 70.9 | 50 - 750 | 19.8 |

| Private Limited | 53.3 | 750 - 2500 | 9.3 | ||

| Public Limited | 1.1 | > 2500 | 1.1 | ||

About 95 per cent of the organisations in the sample were either proprietorship or of private limited in structure. Service sector represented about 71 per cent of the sample.

| Table 4: The Scale Of Investment (In Inr Million) | |||

| Manufacturing | % | Services | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Investment in plant & machinery) | (Investment in equipment) | ||

| Up to 2.5 | 18.7 | Up to 1 | 51.1 |

| 2.5 to 50 | 4.9 | 1 to 20 | 14.8 |

| 50 to 100 | 5.5 | 20 to 50 | 3.8 |

| > 100 | 1.1 | > 50 | 0 |

In the sample, 89.6 per cent of the sample were of small enterprises (In the Indian classification of industries 69.8 per cent were micro-enterprises, and 19.8 per cent were small enterprises), 9.3 per cent were medium enterprises, and 1.1 per cent were large enterprises.

Major Findings

While the first few questions of the questionnaire captured the characteristics of the entrepreneur, the subsequent ones captured information relating to the six dimensions of EM.

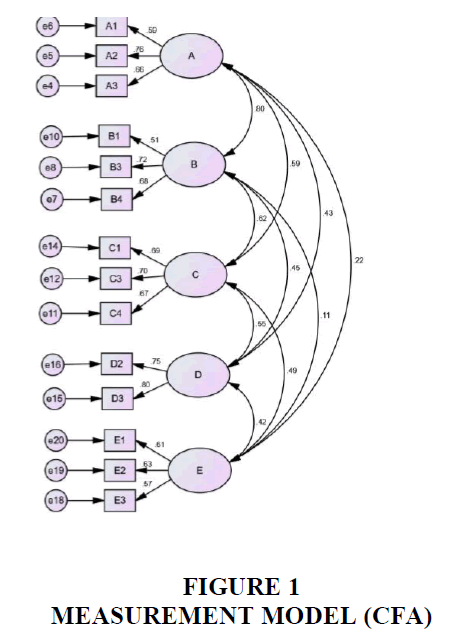

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was done to verify the six dimensions model of EM. The analysis of data was done using structured equation modelling (SEM) with the help of AMOS (version 21) software. There are several fitness index indicators to help in the analysis. After deleting the factor loadings below 0.5, the measurement model, as shown in Figure 1, was built. The fitness index indicators are as shown in Table 5.

| Table 5: Fitness Indices | |||

| Name of Index | Index Name | Index Value | Level of acceptance |

|---|---|---|---|

| GFI | The goodness of fit index | 0.920 | >0.9 |

| RMSEA | Root mean square of error approximation | 0.065 | < 0.08 |

| AGFI | Adjusted goodness of fit index | 0.875 | >0.9 |

| CFI | Comparative fit index | 0.922 | >0.9 |

| TLI | Tucker-Lewis Index | 0.894 | >0.9 |

| Cfmin/df | Chi square/ degree of freedom | 1.76 | < 5.0 |

The values of the fitness index for the model are within the acceptable range. Table 6 shows the composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach alpha for all the constructs in the final model.

| Table 6: Composite Reliability | ||||

| Construct | Items | Cronbach alpha a | AVE | Composite Reliability CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth orientation | A1,A2,A3 | 0.699 | 0.602 | 0.703 |

| Opportunity orientation | B1, B3, B4 | 0.664 | 0.50 | 0.700 |

| Total customer focus | C1, C3, C4 | 0.749 | 0.488 | 0.756 |

| Value creation through networks | D2, D3 | 0.748 | 0.507 | 0.737 |

| Informal market analysis | E1, E2, E3 | 0.639 | 0.523 | 0.765 |

The Cronbach alpha for all was found to be above 0.6, which is acceptable. The average value extracted (AVE) for all was above the acceptable figure of 0.4 (Adcock & Collier, 2001).

Conclusion

The field of entrepreneurial marketing is an emerging field, and so there are several definitions of EM. Researchers have proposed different models to explain the dimensions of EM. In this work, the researchers wanted to empirically verify the six-factor dimensions proposed by Kilenthong et al. in 2015 in the Indian context. The study used Structural equation modelling (Amos V 21) to verify the validity and reliability of the model. While it did not accept the six dimensions, this study accepted the five factors, namely – growth orientation, opportunity orientation, total customer focus, value creation through networks and informal market analysis. The sixth, but not accepted dimension was closeness to market. For the five dimensions of EM, the AVE was higher than the acceptable level of 0.4, convergent validity was established. The various fitness index values were above the acceptable limit, proving the construct validity. The internal reliability was also acceptable as the values of Cronbach alpha was acceptable. The composite reliability was also acceptable.

References

- Adcock, R., & Collier, D. (2001). Measurement validity: A shared standard for qualitative and quantitative research. American political science review, 95(3), 529-546.

- Alqahtani, N., & Uslay, C. (2018). Entrepreneurial marketing and firm performance: Synthesis and conceptual development. Journal of Business Research, xx(x).

- Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modelling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge.

- Collinson, E., & Shaw, E. (2001). Entrepreneurial Marketing - A historical perspective on development and practice. Management Decision, 39(9), 761-766.

- Eggers, F., Niemand, T., Kraus, S., & Breier, M. (2018). Developing a scale for entrepreneurial marketing: Revealing its inner frame and prediction of performance. Journal of Business Research, xxx-xxx.

- Fiore, A. M., Niehm, L. S., Hurst, J. L., Son, J., & Sadachar, A. (2013). Entrepreneurial marketing: Scale validation with small, independently-owned businesses. Journal of Marketing Development & Competitiveness, 7(4), 63-86.

- Hill, J., & Wright, L. (2000). Defining the scope of entrepreneurial marketing: A qualitative approach. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 8(1), 23-46.

- Hills, G. E., & Hultman, C. M. (2011). Academic roots: The past and present of entrepreneurial marketing. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 24(1), 1-10. doi:10.1080/08276331.2011.10593521

- Hills, G. E., & Hultman, C. M. (2013). Entrepreneurial marketing: Conceptual and empirical research opportunities. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 3, 437?448.

- Hills, G., Hultman, C., & Miles, M. (2008). The evolution and development of Entrepreneurial Marketing. Journal of Small Business Management, 46(1), 99-112.

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modelling: a multidisciplinary journal, 6(1), 1-55.

- Jones, R., & Rowley, J. (2009). Presentation of a generic ?EMICO? framework for research exploration of entrepreneurial marketing in SMEs. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 5-21.

- Kilenthong, P., Hills, G. E., & Hultman, C. M. (2015). An empirical investigation of entrepreneurial marketing dimensions. Journal of International Marketing Strategy, 3(1), 1-18.

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modelling. Guilford publications.

- Kocak, A. (2005). Developing and Validating a Scale for Entrepreneurial Marketing. In G. E. Hills, R. D. Teach, J. Monllor, & S. Attaran (Ed.), Proceedings of the Global research symposium on marketing and entrepreneurship (pp. 213-228). The University of Chicago at Illinois.

- Kraus, S., Harms, R., & Fink, M. (2010). Entrepreneurial marketing: Moving beyond marketing in new ventures. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 11(1), 19-34. doi:10.1504/IJEIM.2010.029766

- Lam, W., & Harker, J. M. (2015). Marketing and entrepreneurship: An integrated view from the entrepreneur's perspective. International Small Business Journal, 33(3), 321-348.

- Miles, M. P., & Darroch, J. (2006). Large Firms, Entrepreneurial Marketing and the Cycle of Competitive Advantage. European Journal of Marketing, 40(5/6), 485?501.

- Morris, M. H., Schindehutte, M., & LaForge, R. (2002). Entrepreneurial Marketing: A Construct for Integrating Emerging Entrepreneurship and Marketing Perspectives. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 10(4), 1?19.

- Mort, G. S., Weerawardena, J., & Liesch, P. (2012). Advancing entrepreneurial marketing: Evidence from born global firms. European Journal of Marketing, 46(3-4), 542-561.

- Schmid, J. (2012). Entrepreneurial marketing-Often described, rarely measured. Academy of Marketing Conference. Southampton, UK.

- Simon, D., Kriston, L., Loh, A., Spies, C., Scheibler, F., Wills, C., & Harter, M. (2010). Confirmatory factor analysis and recommendations for improvement of the Autonomy-Preference-Index (API). Health Expectations, 13(3), 234-243.

- Whalen, P., Uslay, C., Pascal, V. J., Omura, G., McAuley, A., Kasouf, C. J., . . . Gilmore, A. (2016). Anatomy of competitive advantage: towards a contingency theory of entrepreneurial marketing. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 24(1), 5-19.

- Yang, M., & Gabrielsson, P. (2017). Entrepreneurial marketing of international high-tech business-to-business new ventures: A decision-making process perspective. Industrial Marketing Management, 64, 147-160.