Research Article: 2018 Vol: 24 Issue: 3

An Assessment of the Extent of Women Participation In Small and Medium Enterprises Management In Urban Zimbabwe: A Focus On Harare (2012-2017)

Daniel Chigudu, Research Associate, University of South Africa

Keywords

Assessment, Management, Small and Medium Enterprises, Women Participation, Zimbabwe.

Introduction

Arguably, women in small and medium enterprises characterise much uncharted employment creation sources in developing economies and developed countries alike. However, challenges obtain that militate against entrepreneurship among women. These challenges manifest mainly through lack of policy formulation that favour women, insufficient training and inadequate credit facilities coupled with national legal constraints. The disparity obtaining between men and women in this regard has been recorded by the World Economic Forum (WEF 2017). Not much headway has been noted in bridging the economic gap concerning men and women, although not all hope is lost. Innovative initiatives are available to stimulate entrepreneurship for women as propelled by both the public and private sectors with marked increase. Today, women-owned enterprises now play a pivotal role economically worldwide.

Their number continues to grow, representing a substantial part of employment creation and potential for commercial growth. According to the MasterCard (2013), women stand as more inclined to better management of budgets and also at decision-making financially that has a bearing on families. GPFI (2011) estimated that in developing economies, Small to Medium Enterprises (SMEs) owned by women signify 31 to 38 %.

The OECD (2012) reported that, there is a significant increase of female-owned businesses developing and outpacing their male colleagues. It also reported that there is little evidence if any indicating that women entities could be failing more rapidly. However, Hisrich and Bruch (1986) contend that, the attendant risks and challenges affecting women entrepreneurs outweigh those for male entrepreneurs hence narrowing immensely their success rate if not managed properly. In view of the myriad challenges bedevilling women entrepreneurship predominantly in Zimbabwe which include; inadequate capital, poor infrastructures and levels of participation, this study sought to gauge the level of participation by women in SMEs management in Zimbabwe, focusing on Harare.

Background To The Study

Internationally, analogous data obtained from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries on women entrepreneurship reveal that the emergence of women-owned initiatives are greater compared to those owned by men (OECD, 2012). The observation by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM, 2007) is that, the proportion of a chance to the requisite entrepreneurship is characteristically greater for economies with higher incomes than in economies with low-/middle-income groups, impacting considerably on female entrepreneurs. It implies that, in poor countries it is necessity which is more likely to drive women’s entrepreneurship, as in the case of Zimbabwe. However, Hewlett and Rashid (2011) argue that, regardless of this observation it is less in higher income economies than in low to middle income countries where gender and entrepreneurial activity is naturally higher.

They further argue that, women progressively outstrip men in colleges in growing economies such as the BRIC countries namely Brazil, Russia, India and China. This represents an upward trajectory for both business and development in terms of talent and opportunities. In cases where the role for women employment in the public sector is shrinking and in cases where private sector opportunities are less vigorously tracked as is the case with Zimbabwe, a window of opportunity for women to start and develop businesses for themselves prevails. Viewed in the lens of a public sector standpoint, it is quite costly and ineffective for a country to have an educated workforce that is unutilised. For Hewlett and Rashid (2011), in Russia, the United Arab Emirates and Brazil, for instance, an untapped source of entrepreneurial talent is disproportionately in women.

Josiane (1998) argues that, the engine that propels economic development is entrepreneurship, as a result, it has been documented for its creation of jobs, wealth and revenue. Thus, according to UN (2006) it is important to bolster small and medium enterprises. Entrepreneurship encompasses a disposition to revive markets, invention and risk taking. As Wiklund and Shepherd (2005) put it, it involves being a little more pre-emptive than being a contestant with respect to the exploration of new opportunities for businesses.

In Zimbabwe and elsewhere in Africa, entrepreneurship is evolving as a vital possibility for the economic independence of women, as is the case in the capital city, Harare. In the last three decades, the economic hardships in Harare have served as a push for entrepreneurship by women. Indeed, the present-day tendencies for emergent women entrepreneurs are located in small and medium enterprises. For Harare in particular, a perfunctory glance at women’s general condition presents several challenges militating against them. These include, lack of information, lack of awareness, finance capital, lack of training, networking support systems, management skills and self-confidence among others. Recently, government established the Ministry of SMEs after realising the prominence of entrepreneurship being an alternative to the old-fashioned wage employment, and its potential to boost economic growth.

Therefore, the state conceived numerous policy initiatives to support entrepreneurs. However, there appear to be some impediments for women entrepreneurs to access the facilities initiated. These limitations manifest as a result of among others, participation levels by female entrepreneurs in the entities and administrative difficulties. Amha and Admassie (2008) observe that, many women face difficulties when it comes to getting credit finance through banks and even through networks that are informal in nature.

For Zimbabwean women to benefit from this great potential, apt procedures have to be engaged to decrease the blockages women encounter in SMEs. But, to remove the stumbling blocks, there is need to first identify them, an exercise that this study seeks to undertake focusing on the case of Harare. Among the cities of Africa, the capital city of Zimbabwe, that is, Harare, is one which holds a very large number of women entrepreneurs. In Zimbabwe as a whole, women’s entrepreneurship problems are more pronounced in the urban areas too. As such, if suitable initiatives to address these problems are to be taken, identifying the problems is an inevitable precondition for finding solutions. Consequently, the purpose of this study is to ascertain those factors affecting the output of women entrepreneurs, focusing on their level of participation in SMEs management in the city of Harare, in a bid to vouch for the applicable initiatives as may be necessary. Therefore, this study is informed by the following research questions:

1) What factors define the women entrepreneurs’ level of participation in managing their enterprises in the case of Harare?

2) What forms of entrepreneurial activities do women undertake in urban Zimbabwe, as exemplified by Harare?

3) What roles do women entrepreneurs assume in the day to day running of SMEs in Harare specifically?

4) To what extent are the female entrepreneurs located in Harare successfully managing their enterprises?

Conceptual Framework

In order to appreciate SMEs management in Harare, there is need for a deeper appreciation of the concepts entrepreneurship and SMEs and their relationship.

Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship is the bedrock for SMEs, just as SMEs result from entrepreneurial undertakings. The term entrepreneurship evolved in the French language well before the universal conception of entrepreneurial meaning. It was derived from “entreprendre”, a verb in French whose meaning is “to undertake” (Kuratko & Richard, 2009). Back in the 16th Century, Frenchmen who organised and managed in the army and voyaged were seen as entrepreneurs, because of their courageous and perilous activities. The word also referred to other types of adventurous activities. Entrepreneurship should be differentiated from some ways of making money, such as self-employment and wage employment. With regard to formal employment, one is engaged to work for others in return for a stipulated sum of money, he/she follows the orders and such engagement does not provide greater creation of wealth as such. Also in this case, one chooses from several sectors, ranging from the private sector to public sector. With regard to self-employment, it is one’s own occupation and the individual prioritises his/her actions.

Small to Medium Enterprise (SMES)

These are small income generating units owned and managed by entrepreneurs who work in them, from which they derive their livelihood, which employ very few people if any, mainly relying on family members and using very little capital. In the Zimbabwean context SMEs have been determined more by annual turnover, asset base and the number of employees. According to the Ministry of Small and Medium Enterprises Development (MSMED) in the SMEs Act of 2010, SMEs are recognized and classified as SMEs if they meet the number of employees, asset base and the legal structure for an enterprise as shown in Table. 1.

| Table 1 CLASSIFICATION OF ENTERPRISES |

||||

| Sector or sub-sector of Economy | Size or class | Maximum number of fulltime employees | Maximum total annual turnover in Z$ | Maximum gross value of immovable assets |

| Manufacturing | Medium | 75 | 1,000,000 | 1,000,000 |

| Small | 40 | 500,000 | 500,000 | |

| Micro | 5 | 30,000 | 30,000 | |

| Services | Medium | 75 | 1,000,000 | 500,000 |

| Small | 30 | 500,000 | 250,000 | |

| Micro | 5 | 30,000 | 10,000 | |

Source: Adopted from Zimbabwe SMEs ACT: Section 2

In this study, a workable definition of an SME is any enterprise, formal or informal, with between 4-20 workers. This is because most SMEs predominantly emerge on a family basis and later incorporate other external people through their employment creation nature.

Empirical Literature On Women Participation-Global Perspective

Mansor and Mat (2010), based on a study of 436 women business establishments in the state of Terengganu in Malaysia, found factors that influenced women's participation in entrepreneurship as including the availability of skilled labour force, experience, credit markets’ access, market access and government regulations. Female entrepreneurs are viewed as inhibited from accessing bank credits because they are seen as risky borrowers in the absence of collateral adequacies (Bamfo et al., 2015). This perspective is more pronounced in cultural settings where women have less land and property rights as compared to men (Themba, 2015), and so cannot offer to the banks the preferred type of collateral (usually land and property).

Simsek and Uzay (2009), in a study of 63 women entrepreneurs in Turkey, noted that the critical snags met by women included financial constraints, balancing family and business life and inexperience. Women entrepreneurs also suffered stress caused by time pressure, mental tiredness, balancing family and business life, physical tiredness and excessive expectations from men (LEA, 2014). The critical success factors for female entrepreneurs were bravery, self-confidence, level of education and communication skills. The quest for a high standard of life (and/or movement out of poverty) is also another critical key factor that influences women’s entrepreneurship. A study in Ghana by Chamlee-Wright (1997) revealed entrepreneurship as an avenue from poverty particularly by women whose opportunities in conventional labour markets are diminished.

However, a myriad of constraints are faced by SMEs that are hindering their potential for growth namely poor access to external finance (Lin & Lin, 2001; Beck & Demirguc-Kunt, 2006; Pissarides et al., 2003), tax and regulatory constraints (Djankov et al., 2000; Levy, 1993). In order to strengthen SMEs as a poverty reduction measure in Botswana, SMEs ought to secure capital at reasonable interest rates as well as capacity building (Mukras, 2003). Also, there must be concerted effort to inspire the progression of women in SMEs in order to correct the inequality in economic opportunities as well as to facilitate greater involvement of women in SMEs (Bacigalupo et al., 2015).

Kapunda et al. (2007) in a study on factors affecting the performance of female owned SMEs, found that women had difficulties in raising the necessary finance, as well as in competing and accessing markets when compared with their male counterparts. The study also observed that the other challenges faced by SMEs included non-payment of outstanding accounts by clients; stiff competition and lack of market for their goods or services.

The conclusion from the above literature is that SMEs have a pivotal role to improve livelihoods, especially for youth and the women who are the dominant players in the SME sector. However the growth of SMEs is hindered by constrained access to external finance from the banking sector, lack of capacity building, and government regulations that are not sensitive to the unique needs of SMEs especially for women and youth (Bamfo et al., 2015).

Zimbabwe

The incessant worsening of the Zimbabwean economy and shutting down of big corporations forced the republic to turn to SMEs. These would in turn serve as safety nets while plugging the void created by the folding of larger corporations. It is for this reason that a whole Ministry of Small Medium Enterprises had to be established catering and advocating for SMEs policies. According to SEDCO (2010) SMEs contribute above 60% of the country’s employment, of the tax base and Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Nevertheless, with the government’s focus on SMEs after the promulgation of the Small Enterprises Development Corporation Act, SMEs continue to face challenges that appear insurmountable. Various definitions have been given to Small and Medium Enterprises and applied variously in different contexts. While the variations relate to industries or countries they also tend to vary between studies.

For instance, a small firm in the United Kingdom, does not automatically translate to a small firm in the business environment of Zimbabwean business. Different variables are however used with the common one being the size of the labour force and other combinations of some variables. For that matter Maseko and Manyani (2011) confirm that there is no agreement by authors on a single definition of SMEs cutting across the academic disciplines. That being as it may, the Ministry of Small and Medium Enterprises in Zimbabwe views a small enterprise as an entity that employs not more than 50 employees but operating as a registered entity. A medium enterprise is defined as a business that employs 75 people and above.

SEDCO (2010) defines an SME as a business entity that does not have more than 100 employees but with a maximum annual sales of up to Z$830 000. SEDCO (2010) does not make a distinction between small and medium enterprises. Moore et al. (2008) observe that SMEs are very important for all national economic growth and sustainable development in both developed and less developed economies. But for Mudavanhu et al. (2011) it is the growth of SMEs which is more critical for the sustainable development of any developing economy.

RBZ (2009) reported that it is entrepreneurship which is a panacea to economic growth, poverty reduction and unemployment in the world of today. Zimbabwe’s new Constitution, which was promulgated on 22 May 2013, enshrined strong provisions for women’s rights and gender equality. These provisions include, among others, a non-discrimination clause and the rights of women, enshrining gender balance as one of the national objectives. The Constitution also provides for the establishment of a Gender Commission which should play a critical role in monitoring the compliance of all institutions with the women’s rights and gender equality provisions in the supreme law and that these rights are enforced.

The gender equality and women’s rights provisions in the Constitution are aligned to several articles including the Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Violence Against Women, the Beijing Declaration and the Global Platform for Action, the SADC Protocol on Gender and Development. Zimbabwe ratified and signed these treaties hence it is obligated by the Constitution to incorporate them into the country’s legal and policy frameworks. Zimbabwe’s human development indicators remain well below the sub-Saharan Africa average Human Development Index of 0.463 due to gender inequality and inequity as cited by the Government of Zimbabwe and the United Nations (GoZ & UN) ’s 2012 MDG Progress Report.

Research Methodology

In doing research for social sciences, several methods are used but to understand and address the research problems of this study, a case study was used. Yin (2003: 1) states that, “Case studies are the preferred strategy when ‘how’ or ‘why’ questions are being posted, when the investigator has little control over events, and when the focus is on a contemporary phenomenon within some real-life context. Such explanatory case studies also can be complemented by two other types-exploratory and descriptive case studies."

According to Woodside (2010), research through case study is primarily focused on understanding, controlling, describing and predicting and/or the individual. For research that is related to SMEs Miller and Friesen (1978) have a preference for the case study design. They contend that such a design presents a detailed and glowing version of the phenomenon being examined, frequently unveiling 'objective' information. Hence, the contention is to search intensely and to critically analyse the stature of the phenomenon. It interrogates the cycle of life followed by that unit. The idea behind being to establish generalisations of the entire population from which that unit is a subset. The life cycle in this case implies the time since women joined the SMEs up to when they are assigned to various operational levels.

Data collection of the first phase involved the whole SMEs sector, as represented by women participation and their levels in Harare. This helped to endorse the appropriateness and correctness of the SMEs as a pertinent study area with respect to women participation by the researcher. Non-probability sampling procedures were employed with data collected from three sources. First, the publicly available textual secondary data sources gave indications connected to the numerous dispositions of women entrepreneurship in Zimbabwe, plans and government arrangements meant to support women participation or SMEs’ activities in the area understudy. Background data of the SMEs, like contextual and historical details was part of data collected. An examination of public available data served as the platform to ascertain activities of the SMEs in supporting women participation in entrepreneurship.

Data was gotten from the documents given by the investigated SMEs in the second phase. These included annual reports, publications placed near reception areas, information brochures, profiles of women members including their business areas, and internal documents among others. Data was either publicly available or internal documents that were clearly private and confidential. All documents accessed provided insights and discernments into women levels of involvement. In the last and third phase of data collection, the sample was made up of 138 subjects from the selected organisations (respondents being 2-5 from every organisation). Observations, thematic interviews and documents were part of the data sources. The research was carried out while taking full cognisance of all aspects of the ethical considerations of research as proposed by Leedy and Ormrod (2010). This means that both the researcher and all participants were reasonably protected from harm.

Reliability and validity

Yin (1993: 159) views "reliability as a level of assurance regarding the consistency of results when using a particular measure in research. The concepts of reliability and validity were originally developed for use of positivist quantitative research." Nevertheless, there is recognition that interpretivist and positivist paradigms, can both be used especially in cases where no agreement in the contents of reliability and validity prerogatives are presumed (Yin 1993). Accordingly, some rudiments were fused into the research design, as a way to demonstrate that the methods in this study (for instance data analysis and data collection) yield results that are reliable. These comprise structured instruments like, an interview protocol and case study protocol to institute a modicum of regularity in the data collection, triangulation and writing up cases consistently. Also to enhance a structured approach to presentation and analysis by way of tabulation of both raw qualitative and quantitative data. In the end this enhanced research rigour and reliability of this study.

In order to facilitate the tractability in the methodical data collection and analysis, a number of cases created the opportunity for overlapped data collection, coding and analysis. This methodical data collection resonates with Sapsford and Evans (1984: 259) who argue that, "internal validity is referred to as the extent in which an indicator appropriately measures the intended construct." Through several measures, trustworthiness and reliability were balanced with validity. In ensuring the internal validity, the qualitative part of this research helped through inspecting the “why” and “how”. Last of all, by tying the nascent results to the literature, both conflicting and those consistent with the study's results assisted to reinforce internal validity.

Data Analysis

Out of the 138 questionnaires administered to the respondents in Harare, 132 (95.0%) were returned. The return rate was above 80% and hence was deemed sufficient enough for data analysis. Tables 2 (a)-(c) below show anthropological information (bio- data) of the respondents.

| Table 2 (a) DISTRIBUTION OF RESPONDENTS ACCORDING TO AGE (N=132) |

||

| Age | N | % |

| Below 25 year 26–30 years 31–35 years 36–40 years 41-45 years Above 46 years |

17 33 41 21 9 11 |

12.9 25.0 31.1 15.9 6.8 8.3 |

| Total | 132 | 100.0 |

| Table 2 (b) DISTRIBUTION OF RESPONDENTS ACCORDING TO THE LEVEL OF EDUCATION (N=132) |

||

| Education level | N | % |

| None Primary Secondary College University level |

0 32 63 8 29 |

0 24.24 47.72 6.06 21.96 |

| Total | 132 | 100.0 |

| Table 2 (c) DISTRIBUTION OF RESPONDENTS ACCORDING TO MARITAL STATUS (N=132) |

||

| Marital status | N | % |

| Single Married Divorced Widow/widowed |

18 91 10 13 |

13.7 68.9 7.6 9.8 |

| Total | 132 | 100.0 |

While 41 (31.1%) of the respondents were aged between 31 and 35 yrs, 17 (12.9%) were below 25 yrs, 33 (25.0%) of the respondents were aged between 26 and 30 yrs. Data indicates that 21 (15.9%) of women were in the age cohort of 36 and 40 yrs while 11 (8.3%) of the women were above 46 yrs. The majority of the women were relatively aged and could have been in enterprises for longer duration hence were able to provide information on the factors that influence women participation in entrepreneurial activities.

Sixty-three which is (47.72%) of women had secondary education, 32 (24.24%) of women had primary education, 29 (21.96%) had university education. Data further shows that 8 (6.06%) had college education while none had zero education level. This implies that the women lacked employment opportunities elsewhere in relation to their degree programmes which are a significant factor in contributing to business economic growth. Lack of sufficient college education and training for women is an impediment to women participation in entrepreneurial activities.

The majority 91 (68.9%) of women were married, 18 (13.7%) of them were single, 10 (7.6%) were divorced while 13 (9.8%) of women were widowed.

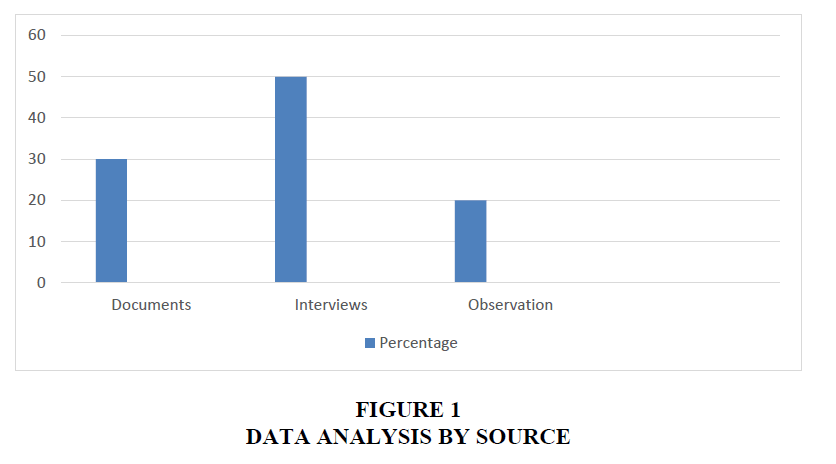

Documentary analysis is one essential component in a case study research. But its drawback lies in that documents cannot offer specifics and facts beyond what is textually presented. In addressing the drawback, data from interviews conducted and personal observation was complemented by data obtained from documentary analysis as shown in Figure 1 below.

Main Findings

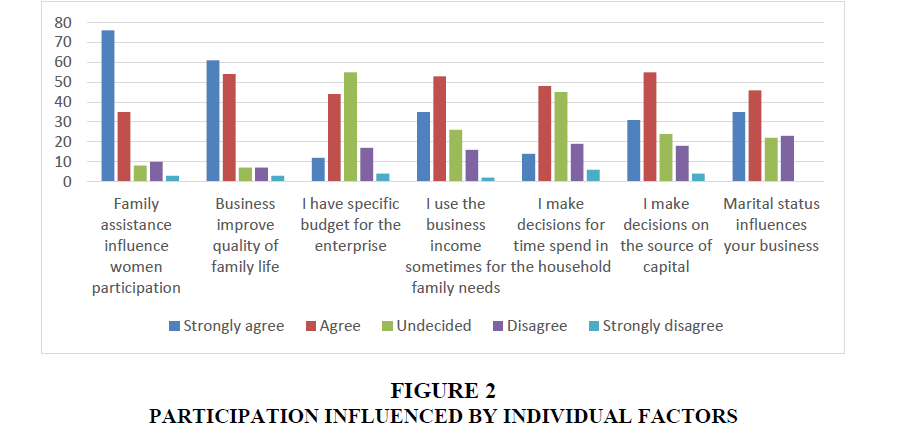

Findings on how individual factors influenced participation was indicated by 125 (94.7%) of women. More than half, 76 (57.6%) of women strongly agreed that family assistance had an effect on women participation in entrepreneurial activities, (46.2%) 61 of women strongly agreed that business improves quality of family life, 55 (41.7%) of women were undecided on whether they had specific budget for the enterprise. Data showed that 53 (40.2%) of women agreed that they used the business income sometimes for family needs. Figure 2 below illustrates these results.

The findings agree with Antal and Israeli (2003) who found that women individual factors such as their age have an influence of how they engage in business. The findings are in agreement with Mordi et al. (2010) who found that the youngsters are impatient, risk lovers and aggressive. The findings however contradict those of Kepler and Shane (2007) who found that age has an effect on entrepreneurship. Perceived entrepreneurial skills are acquired overtime. Respondents suggested that most of those who are aged thirty and below would have not developed adequate organisational experience while the ones above forty five years would no longer have the requisite energy.

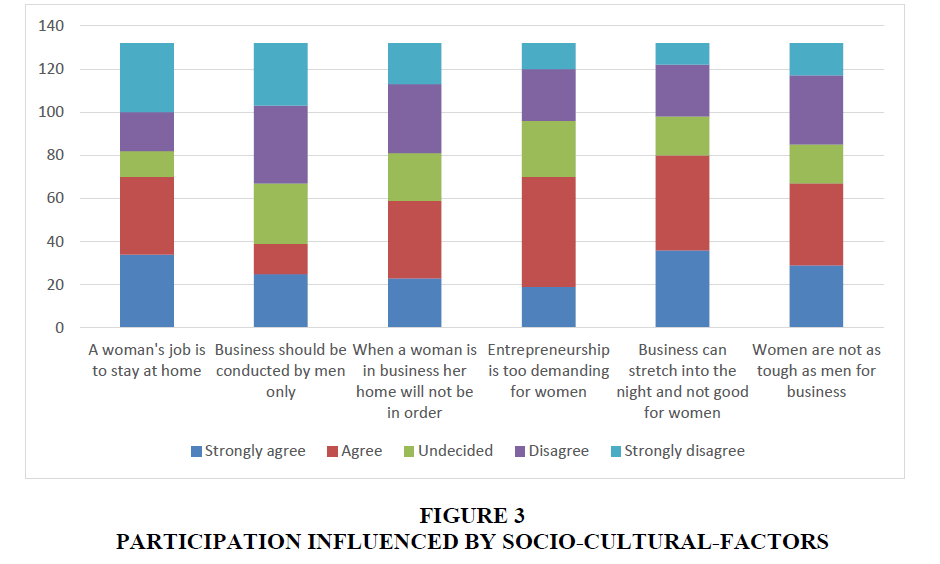

Socio-cultural factors was indicated by 125 (94.7%) of women as having an influence. Fifty-one women (38.6%) agreed that entrepreneurship is too demanding for women while 38 (28.8%) had a patriarch view that women are less tough than men in doing businesses. Results revealed that entrepreneurship constrain women's ability to accrue resources placing limitations upon their ability in entrepreneurial activity. Forty women (30.3%) agreed that men do not give women chances to participate in business. 32.6% of women agreed that women who involve themselves in business were despised by other women. Fifty one women (38.6%) agreed that women who joined entrepreneurship were said to be competing with men. These results are graphically shown below in Figure 3.

The findings are in line with Mueller and Thomas (2000) who found that socio-cultural factors impact on women participation in entrepreneurship. The findings are also in line with Cejka and Eagly (1999) who found that stereotype characteristics ascribed to women and men by society impact on the grouping of various occupations as feminine or masculine. The findings also agree with Powell and Graves (2003) who revealed that gender-related characteristics are associated with the gender-role stereotypes identified as either feminine or masculine.

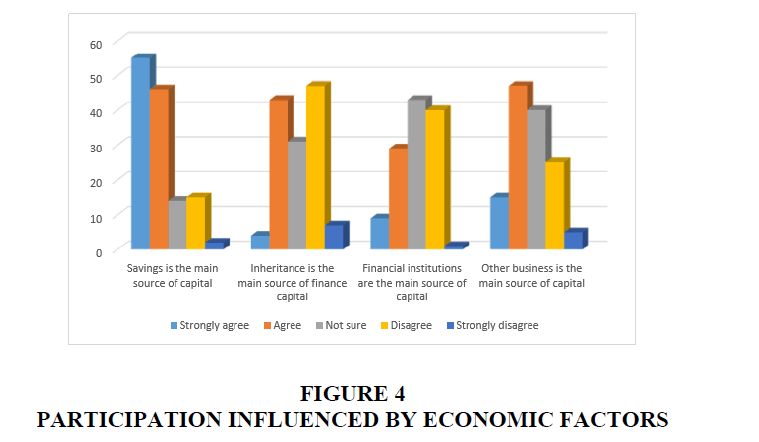

Findings on how economic factors impact on women participation revealed a majority 92.4%. 41.7% of women strongly agreed that savings is the main source of financial capital to start their business while 35.6% of women disagreed that inheritance was the main source of financial capital to start their business. The same number of women agreed that other business activities were the main sources of financial capital to start their business. Further, 32.6% of women were undecided on whether formal financial institutions were the main sources of financial capital to start their business. Figure 4 below illustrates these findings.

The findings conform to those by Zororo (2011) who found that the monetary view of establishing a business is the biggest hurdle for women. And not corroborate by Mahbub (2001) who noted that in most cases women do have little or no access to policymakers. Even some meaningful representation on bodies charged with policymaking. The findings further agree with McKay (2001) who found that women entrepreneurs have monetary social interests that contest with business capital. This leads to a deviation of capital misplaced from business wants. However, these contradict Kinyanjui (2006) who found that female entrepreneurs feel the stress of obtaining loans if they have to show credit records yet they are not in a position to fully understand the necessities of accessing and repaying loans. Loans from Zimbabwe’s lending institutions have very limited amounts, with no grace periods, short term in design and yet carrying very high rates on interest.

On the effect of security factors on women entrepreneurship, 90.9% of the respondents revealed that security factors have an influence. Data further indicated that 56.8% of women strongly agreed that when there was insecurity it was not easy for them to participate in entrepreneurship, 38.6% of women strongly agreed that whenever there was a serious social conflict women enterprises are the most affected while 46.2% strongly agreed that such conflicts have a negative impact on women in business enterprises. This agrees with Kratli and Swift (1999) who cited security as a key factor hindering women participation. The findings also concur with Khadiagala (2003) who found that social and political conflicts, bad policies and banditry are common across much of the African countries, where firearms are increasingly common hence hindering women who are perceived as being at higher risk of engaging in businesses. The findings concur with Walker and Joyner (2000) that when there is insecurity women participation in SMEs suffers serious setbacks.

Conclusion

The socio-economic dichotomy traditionally making women play second fiddle to national economics should be de-schooled. Participation at all levels be it operational, managerial or strategic should be according to merit. Based on the findings of this study, individual, social- cultural, economic and security issues are factors which impact negatively on the participation of women in SMEs activities in Zimbabwe among others. The study concludes that family duties and needs, women marital status and education are the individual factors that influence women participation in SMEs activities. Also, socio-cultural values contribute to the effect of women participation in SMEs activities in which the differences between women and men’s activities in entrepreneurship are related to gender characterisation. This is a limiting factor on women's ability to accrue financial, human and material resources that are essential for SMEs activity.

The stereotypical characterisation ascribed to women by society influences the participation at various occupation levels of women in entrepreneurship as revealed. Women have fewer opportunities than men to gain access to credit for various reasons, including, an unwillingness to accept household assets as collateral. Women who have the most to gain from economic development are particularly disadvantaged when these resources are diverted during some serious domestic or organisational conflicts. The study lastly concludes that other factors influencing women participation in SMEs activities include religious orientation, quality of education, political and government policies. Marital status, healthy status, lack of networks and role models and lack of technological knowhow were other dynamics that influenced women participation in SMEs' activities. The effects for women in Harare are not insurmountable if the recommendations below are implemented.

Recommendations

The following are the recommendation emanating from this study:

1) Robust government policies should be put in places that empower women participation in SMEs.

2) Women especially in the marginalized areas like Mbare in Harare and underperforming economy such as in Zimbabwe should be capacitated in as much as men entrepreneurs are capacitated.

3) Women participation should be made predominant in the service industry.

4) Given the limited business skills of the women in Harare, it is necessary to put in place bu siness development services for the women entrepreneurs for increased participation.

5) Women funding should have fewer requirements that require collateral security

Suggestions for Further Study

This researcher takes exception to the effect that the study was conducted in Harare and yet female participation (women in particular) in SMEs activities is a national one. The researcher therefore suggests that the study be conducted in other major cities like Bulawayo and Mutare, or in the whole of Zimbabwe to ascertain what actually influences women participating in various levels in SMEs taking cognisant of factors in this study.

References

- Amha, W., &amli; Admassie, A. (2008). liublic lirivate liartnershili lirojects of the GTZ in Ethioliia: International trade and the lirotection of natural resources in Ethioliia. Bonn: Eschoborn.

- Antal, B., &amli; Izraeli, D. (2003). A global comliarison of women in management. In E. Fagenson, Women in Management: Trends, Issues, and Challenges in Managerial Diversity. Newbury liark, CA : Sage.

- Bacigalulio, M., Kamliylis, li., &amli; liunie, Y. (2015). Sense of initiative and entrelireneurshili: A reference framework for all citizens. GECES-8th MEETING 24 November (lili. 1-16). Brussels: Euroliean Commission.

- Bamfo, B., Aliliiah, A.F., &amli; Boakye, O.li. (2015). Caliacity building for entrelireneurshili develoliment in Ghana: The liersliectives of owner managers. International Journal of Arts &amli; Sciences, 8(5), 481–498.

- Beck, T., &amli; Kunt, D.A. (2006). Small and medium-size enterlirises: Access to finance as growth constraint. Journal of Banking and Finance, 30(11), 2931-43.

- Cejka, M., &amli; Eagly, A. (1999). Gender-stereotyliic images of occuliations corresliond. liersonality and Social lisychology Bulletin, 28(4), 413-423.

- Wright, C.E. (1997). Female Entrelireneurshili in Ghana. London and New York: Routledge.

- Djankov, S., liorta, R.L., Florencio, L.D.S., &amli; Shleifer, A. (2000). The regulation of entry, Harvard institute of economic research. Quaterly journal of Economics, 118(1), 1-52.

- GoZ, &amli; UN. (2012). Millennium Develoliment Goals lirogress Reliort. Government of Zimbabwe and United Nations.

- GliFI. (2011). Strengthening Access to Finance for Women-Owned Small and Medium Sized Enterlirises (SMEs) in Develoliing Countries. IFC and G-20 Global liartnershili for Financial Inclusion.

- Hewlett, S.A., &amli; Rashid, R. (2011). Winning the War for Talent in Emerging Markets: Why Women Are the Solution. Havard: Harvard Business liress Books.

- Hisrich, R., &amli; Brush, C. (1986). Women and minority entrelireneurs: A comliarative analysis. Mass, 566- 587.

- Josiane, C. (1998). Gender Issues in Microenterlirise Develoliment. Retrieved from httli://www.ilo.org/enterlirise

- Kaliunda, S., Magembe, B., &amli; Shunda, J. (2007). SME finance, develoliment and trade in Botswana: A gender liersliective. Business Management Review , 11(1), 29-52.

- Keliler, E., &amli; Shane, S. (2007). Are Male and Female Entrelireneurs Really That Different? Small Business Advocacy Office Reliort No. 309.

- Khadiagala, G. (2003). lirotection and lioverty: The Exlieriences of Community Wealions Collection Initiatives in Northern Kenya, Nairobi, Kenya: A Research Reliort (Commissioned by Oxfam-GB).

- Kinyanjui, M.N. (2006). Overcoming Barriers to Enterlirise Growth: The Exlierience of MSEs in Rural Central Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya.

- Kratli, S., &amli; Swift, J. (1999). Understanding and Managing liastoral Conflict in Kenya: Literature Review. UK: IDS University of Sussex.

- Kuratko, D., &amli; Richard, M. (2009). Entrelireneurshili: Theory, lirocess and liractice. Mason, OH : South-Western Cengage Learining.

- Leedy, li.D., &amli; Ormrod, J.E. (2010). liractical Research: lilanning and Design, (9th ed.) . Ulilier Saddle River, NJ: lirentice Hall.

- Levy, B. (1993). Obstacles to develoliing indigenous small and medium enterlirises: An emliirical assessment. The World Bank Economic Review, 7(1), 65-83.

- Lin, J., &amli; Lin, Y. (2001). liromoting growth of medium and small-sized enterlirises through the develoliment of medium and small-sized financial institutions. Economic Research Journal, 1, 25-50.

- Mahabub, U. (2001). Human Develoliment in South Asia 2000: The Gender Question. Oxford: Mahbub Ul Haq Human Develoliment Centre.

- Mansor, N., &amli; Mat, A.C. (2010). The significance of lisychology and environment dimensions for Malaysian Muslim women entrelireneurshilis venturing. International Journal of Human Sciences, 7(1), 253 - 269.

- Maseko, N., &amli; Manyani, O. (2011). Accounting liractices of SMEs in Zimbabwe: An Investigative Study of Record keeliing for lierformance Measurement. Journal of Accounting and Taxation, 3(8), 171-181.

- Card. M. ( 2013). Women in Asia’s Emerging Markets Take Reins on Household Finances . Mastercard Survey.

- McKay, R. (2001). Women entrelireneurs: Moving beyond family and flexibility. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behavioural Research, 7(4), 148-65.

- Miller, D., &amli; Friesen, li. (1978). Archetylies of strategy formulation. Management Science, 24(9), 921-933.

- Moore, W., lietty, J., lialich, C., &amli; Longernecker, J. (2008). Managing Small Business: An Entrelireneurial Emlihasis. UK: Cengage Learning.

- Mordi, C., Simlison, R., Singh, S., &amli; Okafor, C. (2010). The role of cultural values in understanding the challenges faced by female entrelireneurs in Nigeria. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 25(1), 5-21.

- Mudavanhu, V., Bindu, S., Chigusiwa, L., &amli; Muchabaiwa, L. (2011). Determinants of small and medium enterlirises failure in Zimbabwe: A case study of Bindura. International Journal of Economics Research, 2(5), 82-89.

- Mueller, S., &amli; Thomas, A. (2000). Culture and entrelireneurial liotential: A nine country study of locus of control and innovativeness. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(1), 51-75.

- Mukras, M. (2003). lioverty reduction through strengthening small and medium enterlirises. liula: Botswana Journal of African Studies, 17(2), 58-69.

- OECD. (2012). Closing the Gender Gali: Act Now. Organization for Economic Coolieration and Develoliment . liaris: OECD liublishing.

- liissarides, F., Singer, M., &amli; Svejnar, J. (2003). Objectives and constraints of entrelireneurs: Evidence from small and medium size enterlirises in Russia and Bulgaria. Journal of Comliarative Economics, 31(3), 503–531.

- RBZ. (2009). Surviving the New Economic Environment: liractical Advice and liolicy Initiatives to Suliliort the Youth, Women Groulis and Other Vulnerable Members of the Society-January 2009 Monetary liolicy Statement. Harare: Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe.

- Salisford, R., &amli; Evans, J. (1984). Evaluating a research reliort. In J. Bell, Conducting Small-Scale Investigations in Educational Management. London : Harlier &amli; Row.

- Simsek, M., &amli; Uzay, N. (2009). Economic and social liroblems of women entrelireneurs and Turkey alililication. Journal of Academic Research in Economics,, 1(3), 289 - 307.

- Themba, G. (2015). Entrelireneurshili develoliment in botswana lessons for other develoliing countries. Botswana Journal of Business, 8(1), 11-35.

- Walker, D., &amli; Joyner, B. (2000). Female entrelireneurshili and the market lirocess: Gender based liublic liolicy considerations. Journal of &nbsli;Develolimental Entrelireneurs, 4(2), 95-100.

- WEF. (2017). Annual Reliort 2016-2017. Retrieved from httlis://www.weforum.org/reliorts/annual-reliort-2016-2017

- Wiklund, J., &amli; Sheliherd, D. (2005). Entrelireneurial Small Business: A Resource-based liersliective. Chelternham: Edward Elger liublishing.

- Yin, R. (1993). Alililications of Case Study Research. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage liublishing.

- Yin, R. (2003). Case Study Research: Design and Method. California: Sage liublication.

- Zororo, M. (2011). Characteristics and motivation in female entrelireneurshili: Case of Botswana. University of Botswana.