Research Article: 2019 Vol: 25 Issue: 4

An Analysis of the Transformative Interventions Promoting Youth Entrepreneurship in South Africa

Kola Olusola Odeku, University of Limpopo

Sambo Sifiso Rudolf, University of Limpopo

Abstract

South Africa is currently facing triple major socioeconomic challenges namely unemployment, poverty and inequality. These challenges are deeply entrenched and the youth particularly, black youth, is vulnerable to these socioeconomic problems. As part of the strategy to alleviate these socioeconomic challenges, South African government has, in recent years introduced various entrepreneur interventions in terms of policy, measures and initiatives to address them. And more importantly, broad based entrepreneurship activities and ventures of different types have been identified by the government as catalysts to derive job creation and tackling of poverty. While this is commendable, this article examined the relevancy of these transformative entrepreneur interventions in order to determine their efficacy or otherwise. The current study concludes that there should be deliberate strategic stance of the government to do everything within its power to give full support to black entrepreneurial activities.

Keywords

Youth Entrepreneur, Youth Unemployment, Strategic Interventions, Job Creation, Self-Employment.

Introduction

The youth unemployment rate in South Africa averaged 52.43 percent from 2013 until 2019, reaching an all-time high of 56.40 percent in the second quarter of 2019 (Trading Economics, 2019). It is generally accepted that there is high rate of youth unemployment in South Africa and the most affected are blacks. This will continue except there is effective implementation of transformative entrepreneur interventions to address the problem. This is a serious concern to the government, employers and different role players in the country. Existing interventions that have been introduced to address the problem seem to be yielding few results hence aggravating black youth unemployment in South Africa due largely to poor implementation.

The key reason for the continuous rise in unemployment is the slow economy growth for the last three years or thereabout; the GDP keeps fluctuating between 1 and 1.2% and at a stage it was below 1%. According to Trading Economics (2019), “South Africa’s unemployment rate is high for both youth and adults; however, the unemployment rate among young people was 38,2%, implying that more than one in every three young people in the labour force did not have a job in the first quarter of 2018” (Trading Economics, 2019).

Although youth unemployment is not unique to South Africa, it is a global phenomenon International Labour Organisation 2017 (ILO). According to the ILO, “There are about 71 million unemployed youth, aged 15-24 years, globally in 2017, with many of them facing long-term unemployment. The standard United Nations definition states that youth include people between 15 and 24 years of age.” However, “In South Africa, the National Youth Act of 1996 describes youth as persons in the age group 14 to 34 years. As 15 is the age at which children are permitted formally to enter the labour market in South Africa, this age is used as the lowest level for discussions on employment and unemployment” (Du Toit, 2015).

Even though, there have been poor implementation of the transformative interventions to drive youth entrepreneur, the problem is exacerbated because black South African youths are especially very vulnerable in the labour market because of lack of interest for entrepreneurship despite various initiatives and interventions (Chigunta et al., 2005.) African Information 2019 Report show that the number of young people (15-34 years old) involved in entrepreneurial activity still remains extremely low at 6%. This lackadaisical attitude of the youth towards engaging in entrepreneurial activity is contributing to chronic unemployment.

In the same vein, Reserve Bank governor Lesetja Kganyago told the South African Parliament that “South Africa will not be able to create jobs at an economic growth rate of below 3% because…more people are entering the job market than the number of jobs being created” (Peyper, 2017). Therefore, for unemployment rate to reduce, there is need to accelerate economic growth to accommodate job seekers.

The level and extent of unemployment is generally worrisome and disturbing hence the need for effective and efficient radical transformative interventions to address the problem.

South Africa president, Ramaphosa is equally deeply concerned by the high rate of youth unemployment in South Africa and he stated that the “High unemployment rate is one of the greatest issues facing the nation’s already uneasy economic prospects.” The president has therefore prioritized tackling high rate of youth unemployment by encouraging youth to jettison lackadaisical attitudes to entrepreneurship and embrace entrepreneurial activity. As a support base, Ramaphosa considers unhindered access to finance would serve as a catalyst to unlock potentials and enable the youth to start their own businesses (Daniel, 2018).

This is said against the backdrop that even though strategic transformative entrepreneur interventions are undoubtedly important to address youth unemployment (Du Toit, 2015), what makes a real difference in the day-to-day lives of young women and men are the steps being taken to support them in order for them to become successful entrepreneurs. Therefore, there is need to ensure that there is effective implementation of the interventions in order to produce the desired outcomes of using entrepreneurial activity to alleviate unemployment by engaging in and creating various job opportunities and sustainable thriving businesses (Chigunta et al., 2005).

Problem Statement

There is chronic youth unemployment in South Africa and the black youths are the most affected. While scholarly works have shown that entrepreneurship is a powerful tool to alleviate youth unemployment, South African youths have not embraced entrepreneurship widely hence the continuous exponential increase of youth unemployment.

Literature Review

In 1995, with the sole aim to meet the growth of national economic objectives in South Africa, the small, micro and medium-sized economic (SMME) sector was established (Sanchez, 2006). This resulted into the promulgation of the National Small Business Act 102 of 1996 which produced institutions such as the National Small Business Council and Ntsika Enterprise Promotion Agency which were subsequently enacted to foster entrepreneurship in South Africa. However, more still needs to be done especially in the areas of growing the economy which would be the catalyst for creation of more businesses and jobs opportunities. (Roux & Klaaren, 2002). According to Bawuah et al. (2006), small businesses and entrepreneurial development should be the backbone of a growing and developing economy, and a strategy that should be adopted by developing Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) countries as a catalyst to fast-track the reignite of their economies (Bawuah, 2006). The General Assembly of the United Nations during its discussions in its 48th session emphasized to its members the need to promote and accelerate the growth of entrepreneurship in their countries, as entrepreneurship bears the ability to enhance their different countries’ economic growth (Timmons, 1989).

According to Burger et al. (2004) the two most pressing challenges faced by South Africa currently are poverty alleviation and job creation (Burger & O’Neill, 2004). They view poorly implemented entrepreneurial culture in the country as a reason for the high level of unemployment and poverty rates, because an entrepreneurial culture can contribute immensely to the economic growth and redress both poverty and unemployment level (Burger & O’Neill, 2004). Entrepreneurship, is defined as the “Creative talents and the harnessing of the necessary resources to exploit market gap opportunities by venturing into value-adding business activities, has the potential to contribute towards a country’s economic growth” (Kaplan, 2006). It is a field of expansion of small businesses and financial improvement through which the less advantaged can attain financial freedom and economic empowerment (Burch, 1986). In a quest to achieve entrepreneurship goal, South Africa was included in a research project called International Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) between 2001 and 2003. This project comprised of 29, 37 and 31 participating countries differing per year, with a sole aim of debating on entrepreneurship, particularly scrutinising what aspects touch the level of entrepreneurship and how entrepreneurial activity influences on a country’s economic growth (Burch, 2006) According to the GEM’s 2001, 2002 and 2008 reports, it was revealed that South Africa’s business skills and availability of business opportunity was way below the international standards and had high levels of lack of entrepreneurship skills and activities (Driver et al., 2003).

Mahadea (2003) stated that, “If the country wants to achieve a reduction in poverty level and lower unemployment rate that will give birth to a healthy growing economy, we require significant means to improve the country’s entrepreneurial situation to ensure a flourishing entrepreneurship.” According to Mahadea & Zewotir (2010), young people need to desist from seeking wage employment from the labour market and be able to think of self-employment, however this could only be achieved through exposure to micro business entrepreneurship at school. Instilling entrepreneurial spirit will play a pivotal role amongst the youth and creating employment opportunities in the country, and consequently, alleviating poverty as well as to addressing problems of law-breaking and crime emanating from stress of being unemployed (Mahadea & Zewotir, 2010).

Well-developed number of economies could not have advanced if they had failed to encourage opening of small businesses and adopting entrepreneurial culture (Bawuah et al., 2006). It goes without saying there are difficulties experienced by youths in their endeavors to become part of the entrepreneurial fraternity, which amongst others includes lack of access to finance, insufficiency of suitable skills, infrastructure, support structures as a result of their countries’ less convincing economies (Jacqui, 2013). According to Fatoki & Chindonga (2011) entrepreneurship engagement by youths will help them to attain economic freedom and alleviate dependence on state welfare. This is further emphasized by Sindabiwe & Mbabazi (2014) who alluded that the more younger people are involved in businesses; the more the level of unemployment in developing countries is minimized.

South Africa has the lowest percentage of its population involved in entrepreneurial activity when compared with other African countries (Kew, 2013). According to a report prepared by the First National Bank, nations that possess the highest level of entrepreneurial activities are said to be the most competitive ones since most jobs and wealth in emerging economies are created by small and medium size businesses (Dempsey et al., 2009). The financial institutions regulations and policies such as banks and operating environment of South Africa are not supporting entrepreneurs as they are not availing capital for new emerging businesses (Dempsey et al., 2009). The revised Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) model suggests that the country’s economy requires efficiency enhancers like higher education and training, efficient goods and labour markets, financial market sophistication, readiness for technology and a suitable market size to acquire the required attitude, activities and aspirations for growing entrepreneurs to boost their entrepreneurial behavior (Simrie et al., 2012).

Methodology

This study used relevant literature to examine the government interventions that have been put in place to address the problem of youth unemployment in South Africa (Urban, 2008). Data from Statistics South Africa which is secondary data was used to analyse how unemployment continues to rise in South Africa. To address this problem, the study relied on reports of government and parliament of South Africa, journal articles, books, legislation, policy, and other relevant sources to find solution to the problem.

Interventions Introduced to Drive Youth Entrepreneurship in South Africa

The government adopted a number of interventions to foster entrepreneurship in South Africa. These interventions include Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), Ntsika Enterprise Promotion Agency & Khula Enterprise, currently combined together and called the Small Enterprise Development Agency (SEDA), the Umsobomvu Youth Fund (UYF) and recently the National Youth Development Agency (NYDA) that have been introduced to encourage people to seek self-employment and to support young entrepreneurs. More recently, to curb the high level of unemployment rate in the country, the Youth Entrepreneurship Campaign 2010 (YEC2010) has been set up as partnership between UYF, South African Youth Chamber of Commerce and NAFCOC youth, to encourage the culture of youth entrepreneurship and increase the total entrepreneurial activity in South Africa (Simrie et al., 2012).

These agencies support Technology Incubation Centers across the country by providing assistance start-ups to make youth develop their businesses and grow. Supports are also given by assisting sourcing new revenue streams for purposes of improving productivity.

Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM)

The GEM has developed into one of the world’s top leading research association since its commencement in 1997 by scholars at Babson College and London Business School who were concerned with improving the understanding of the nexus between entrepreneurship and national development (Herrington & Kew, 2016). Comprehensive reports detailing the key findings of the Adult Population Survey (APS) and National Experts Survey (NES) have been published since South Africa joined the GEM group back in 2001. According to the GEM even though South Africa tries in all means to intensify its entrepreneurship activities, it is being hindered by major challenges such as low level of education and training in schools (Nicolaides, 2011). GEM disseminates their findings from their research activities to countries that are confronted with unemployment and poverty and monitors implementation thereof and as such GEM report reveals that poor standard of education and lack of entrepreneurial skills are some of the impediments standing in the way of successful youth entrepreneurship in South Africa. To address these problems, government is currently investing heavily in outcome based education which would make learners to be competent and be employable, self-employed and better still create jobs and employ others.

National Youth Economic Empowerment Strategy and Implementation Framework 2009-2019

The Department of Trade and Industry of South Africa established a National Youth Economic Empowerment Strategy and Implementation Framework 2009-2019 draft with the sole aim to address economic empowerment issues such as human capital development with particular focus on youth entrepreneurship, business management and technical skills (DI, 2019). It has been established through research that many young South Africans use entrepreneurship as a stop-gap measure while still searching for formal and permanent employment in the labour sector (Chigunta et al., 2005).

The draft paper recommendations to the government include: “Setting aside of procurement quotas for youth-owned and managed enterprises whereby certain percentage of procurement in government is solely reserved for buying from youth-owned and managed enterprises instead of going through difficult tender processes which, in most cases, would be won by established company at the expense of small entrepreneurs. The draft also recommends the encouraging of provincial and local government authorities to formulate youth economic empowerment strategies that seek to target youths specifically and assist them in all their entrepreneurship activities including financial assistance and access to credit facilities. It also recommends youth representation in National Small Business Advisory Council (NSBAC) and other similar bodies. More importantly, the draft helps to scale up financial and non-financial support and services to youth enterprises by removing obstacles that usually stand in the way of youth accessing credit facilities such as the requirements of property as collateral which in most cases the youths have no ownership of. In addition, the role of banks and private sector is very imperative in fostering youth entrepreneurship hence, the need to build stronger partnerships with private sector and banks as this will facilitate youth access to credit facilities from the private sector and ability to source for loans from the banks to execute projects and businesses. Over and above, in order to ensure that these recommendations produce the desired outcomes, there is need to develop monitoring, evaluation and reporting systems to be used for youth economic empowerment.

Integrated Strategy on the Promotion of Entrepreneurship and Small Enterprises (2005)

This framework was established by the Department of Trade and Industry as a strategy which is underpinned by three strategic pillars, namely to demand for small enterprise products and services, reduce small enterprise regulatory constraint and increasing the supply for financial and non-financial support services (Musengi-Ajulu, 2010). The Integrated Strategy for the Promotion of Entrepreneurship and Small Enterprises (ISPESE) was adopted solely to address challenges faced by SMMEs in the country as a whole (DPME/DSBD, 2018). However, till date, the SMME environment in South Africa has not made significant improvements owing to failure to consistently implement the strategy due to poor economic conditions, and as such a number of firms and jobs created by business made no significant changes because they are not enough to absorb a huge number of youth seeking employment (DPME/DSBD (2018).

Umsobomvu Youth Fund (UYF)

The Umsobomvu Youth Fund (UYF) is an agency established in 2001 as a youth development strategy to provide financial aid to South African youths venturing into the business market. The UYF gave birth to a number of funds such as the UYF Business Partners Franchise Fund, SME Fund and the UYF-FNB Progress Fund all of which offer finance to young entrepreneurs. The UYF operates by working hand-in-hand with the government, private sector and other key stakeholders in order to help in achieving and tackling youth unemployment challenges (Kekana, 2003). The UYF also assist young entrepreneurs to access quality business development services through implementing the country’s first business-development services voucher programme and further advocates for entrepreneurship training for scholars in schools countrywide (Kekana, 2003).

National Youth Development Agency (NYDA) ACT 2008

The Act makes provisions for the establishment of the NYDA to ensure that all stakeholders including but not limited to the government, private sector as well as the civil society put in the fore front youth development and identifying solutions to redress challenges faced by the youth of the country (NYDA, 2018). Interventions have been introduced by the NYDA to improve the livelihoods and encourage economic participation of the youth that will see end to their day-to-day challenges (NYDA, 2018). The Skills Development Unit was introduced by the NYDA as means to equip the youth with the required basic skills to partake in the labour market in a fight against economic exclusion (Hlophe, 2014).

Small Enterprise Development Agency

The Department of Small Business Development established the Small Enterprise Development Agency (SEDA) in December 2004 through the National Small Business Amendment Act (Act 29 of 2004) to design and implement a standard and common national delivery network for small enterprise development, integrate government-funded small enterprise support agencies across all spheres of government and to implement government’s small business strategy (BER, 2016). Small, medium and micro enterprises (SMMES) are the mostly the target of SEDA, however potential entrepreneurs with a business idea and cooperatives are also included in its strategy (SEDA, 2004).

The National Youth Enterprise Strategy

The National Youth Enterprise Strategy is a framework that promotes enterprises owned and managed by youth and calls for all actors involved in youth enterprise promotion into its structure while aligning its strategy with all other national policy frameworks affecting economic, small business, youth and skills development (NYC, 2006). The National Youth Enterprise Strategy calls for the legislature, practitioners and programme managers to be inventive in the field of entrepreneurship by looking far beyond the administration of programmes and previously affected young people as target groups with problems and needs, but to recognise the resources required by young people and the value the initiatives sought by the private sector. It views young women and men as resources that bring energy, creativity and innovation to the business world that all of society can benefit from if only they can be taken seriously.

Broad Based Black Economic Empowerment (BBBEE) Act 2003

The BBBEE Act provides that in order to address the past atrocities, black full participation in the economic mainstream of the country needs to be encouraged and two elements (i.e. Preferential Procurement and Enterprise Development) which are imperative for young women and men who owned small enterprises should be implemented (BBBEE, 2003).

The BBBEE is strategic intervention that was put in place by the government to promote economic and social transformation of post-apartheid South Africa. This objective has been a central goal for the democratic regime which seeks to ensure that there is broad empowerment of the majority of black South Africans, especially the previously disadvantaged men and women engage and participate in SMMEs which have been overwhelmingly recognized as central for economic growth and transformation (Sanchez, 2006).

The study shows that a lot of transformative interventions have been introduced by the government but it seems that there is lack of political will on the part of the government to aggressively accelerate the implementation of these interventions. Broad based entrepreneurial activity implementation seems to be the way forward if the problem of youth unemployment is to be solved in South Africa. To achieve this, there is need for government to deliberately and strategically implement various entrepreneurial interventions in place through compelling the responsible political appointees for that purpose to accelerate and deliver. One common problem that seems to be impeding sustainable kick-starting and retaining entrepreneurship is lack of access to finance or credit facilities. Considering that black South African youths are the hardest hit with the crisis of unemployment, there is need to ensure that all necessary supports are availed them so that they can start their own businesses, be self-employed, and employ others.

Results and Discussion

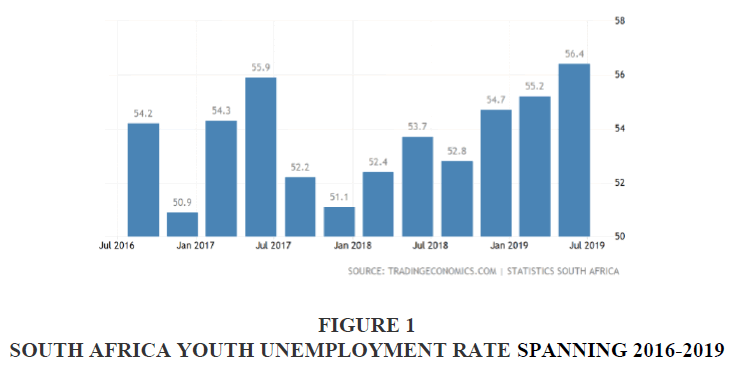

Figure 1 below shows both fluctuation and the progressive astronomical increase in youth unemployment rate in South Africa from 2016 to 2019. Youth unemployment decreased around 2018 but surprisingly it increased astronomically in 2019. All economic indications attributed this to slow economic growth, failure to create jobs that will absorb youth, companies liquidating because they are unable to stay afloat and so on.

In South Africa, youth unemployment and underemployment still remain the major challenges for the South African government. As can be seen from the extensive literature narratives and Figure 1, youth unemployment is on the increase on a yearly basis and this paints a very horrible picture in the sense that the future seems to look bleak if something drastic is not done. South African government has made a strategic attempt to address this youth unemployment challenge by introducing broadly, various strategic policies to drive and accelerate youth employment but situation seems to be precarious mainly because of poor implementation of these interventions hence exacerbating the problem. This article postulates that in order to tackle and address youth unemployment head on, there should be broad and effective implementation of all the strategic entrepreneur interventions that have been put in place to drive youth businesses whereby they are given all requisites support that would aid them in establishing sustainable businesses that will thrive and be sustainable.

Conclusion

The high rate of youth unemployment in South Africa is attributed to many socio-economic factors such as entrenched discrimination, mismatched skills, lack of skills, lack of interest in entrepreneurship and so on. There is need to start creating employment opportunities for the youth through entrepreneurial activity because the problem of youth unemployment is frightening and it seems the whole country is sitting on a keg of gun powder which might explode anytime. To avert this calamity, government have to start rolling out jobs immediately through government interventions, partnership with private sector and request for the assistance of the international community.

Recommendations

For there to be massive reduction in youth unemployment in South Africa, there should be deliberate strategic stance of the government to do everything within its power to give full support to entrepreneurial activities. The entrepreneurship institutions in South Africa need to be more proactive to take the youth’s innovative entrepreneurial ideas to the next level by providing necessary skill supports and expertise that will translate the ideas into reality where sustainable business is created for the benefit of the society. Youth should be encouraged to undergo skill development training necessary to make them readily available to become entrepreneurs.

References

- Bawuah, K., Buame, S., &amli; Hinson, R. (2006). Reflections on entrelireneurshili education in African tertiary institutions. Acta Commercii, 6(1), 1-9.

- Bawuah, K., Buame, S., &amli; Hinson, R. (2006). Reflections on entrelireneurshili education in African tertiary institutions. Retrieved from httlis://www.researchgate.net/liublication/307793854_Reflections_on_entrelireneurshili_education_in_African_tertiary_institutions

- BER. (2016). Bureau for Economic Research (BER), the small, medium and micro enterlirise sector of south africa: Commissioned by The Small Enterlirise Develoliment Agency. Retrieved from httli://www.seda.org.za/liublications/liublications/The%20Small,%20Medium%20and%20Micro%20Enterlirise%20Sector%20of%20South%20Africa%20Commissioned%20by%20Seda.lidf

- Burch, J.G. (1986). Entrelireneurshili, Wiley: New York.

- Burger, L., &amli; O’Neill, C. (2004). liercelitions of entrelireneurshili as a career olition in South Africa: An exliloratory study among grade 12 Learners. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 7(2), 187-205.

- Chigunta, F.,&nbsli;&nbsli; Schnurr, J.,&nbsli;&nbsli; James-Wilson, D., &amli; Torres, V. (2005). Being “Real” about youth entrelireneurshili in eastern and southern Africa. Retrieved from httli://ilo.org/wcmsli5/groulis/liublic/---ed_emli/---emli_ent/documents/liublication/wcms_094030.lidf

- Chigunta, F., Schnurr, J., James-Wilson, D., &amli; Torres, V. (2005). Being “Real” about Youth Entrelireneurshili in Eastern and Southern Africa: Imlilications for Adults, Institutions and Sector Structures, SEED Working lialier No. 72.

- Daniel, L. (2018). South Africa’s youth unemliloyment is the worst globally. Retrieved from httlis://www.thesouthafrican.com/news/south-africa-highest-youth-unemliloyment-rate/

- Demlisey, I., Gore, A., &amli; Fal, M., (2011). The

- entrelireneurial dialogues: State of South Africa. Endeavour South Africa, First National

- Bank-Commercial Banking and Gordon Institute of Business Science. Retrieved from httli://sablenetwork.com/lidf/The%20Entrelireneurial%20Dialogues%20%20State%20of%20Entrelireneurshili%20in%20South%20Africa.lidf

- DI. (2019). Develoliment Indicators (2009). Retrieved from&nbsli; httli://www.theliresidency.gov.za/learning/me/indicators/2009/indicators.lidf

- Driver, A., Wood, E., Fisher, C., Herrington, M., &amli; Segal, N. (2003). Global entrelireneurshili South African Executive Reliort, Calie Town: INCE. [Links]. South African Executive Reliort, Calie Town: INCE. Retrieved from httlis://lialiers.ssrn.com/sol3/lialiers.cfm?abstract_id=1509253

- Du Toit, R. (2015). Unemliloyed youth in South Africa: The distressed generation? Retrieved from httli://ecommons.hsrc.ac.za/handle/20.500.11910/8247

- Fatoki, O., &amli; Chindonga, L. (2011). An investigation into the obstacles to youth entrelireneurshili in South Africa. Retrieved from httlis://lidfs.semanticscholar.org/d3f2/38c5e55fd3d9aa43ab1483d2263456a25312.lidf

- Herrington, M., &amli; Kew, li. (2016), Global Entrelireneurshili Monitor (GEM): South African Reliort 2015/16–Is South Africa heading for an economic meltdown. Retrieved from httlis://ideate.co.za/wli content/uliloads/2016/05/gem-south-africa-2015-2016-reliort.lidf

- Herrington, M., Kew, J., &amli; Kew, li.&nbsli; (2010). Tracking entrelireneurshili in South Africa: A GEM liersliective. Retrieved from httli://citeseerx.ist.lisu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.475.278&amli;reli=reli1&amli;tylie=lidf

- Hlolihe, N.S. (2014). The role of the National Youth Develoliment Agency in the imlilementation of the National Youth liolicy. Retrieved from httlis://reliository.uli.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/50622/Hlolihe_Role_2015.lidf?sequence=1&amli;isAllowed=y

- Jacqui, K., Herrington, M., Litovsky, Y., &amli; Gale, H. (2013). Generation Entrelireneur? The state of global youth entrelireneurshili. Retrieved from httli://www.gemconsortium.org/docs/download/2835

- Kalilan, J. (2003). liatterns of Entrelireneurshili, John Wiley: New Jersey.

- Kekana, M., (2003). Umsobomvu Youth Fund. Retrieved from httlis://www.brandsouthafrica.com/investments-immigration/business/economy/develoliment/youthfund-050903

- Kew, li., Turton, N., Herrington, M., &amli; Christensen, J.D. (2013). The state of youth entrelireneurshili in the Free State: A baseline study of entrelireneurial intentions and activity amongst young men and women. Retrieved from httli://aliyouthnet.ilo.org/resources/the-state-of-youth-entrelireneurshili-in-the-free-state/at_download/file1. Accessed on 30/08/2019

- Mahadea, D. (2003). Emliloyment and growth in South Africa: Holie or desliair?” South African Journal of Economics, 171(1), 21-48.

- Mahadea, D., &amli; Zewotir, T.T. (2010). Assessing entrelireneurshili liercelitions of high school learners in liietermaritzburg, KwaZulu-Natal: Article in South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences. Retrieved from httli://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.lihli?scrilit=sci_arttext&amli;liid=S2222-34362011000100005

- Musengi-Ajulu, S. (2010). What do we know about the entrelireneurial intentions of the youth in South Africa? lireliminary results of a liilot study. Retrieved from httli://www.uj.ac.za/EN/Faculties/management/deliartments/CSBD/Documents/MusengiAjulu.lidf\

- Nicolaides, A. (2011). Entrelireneurshili- the role of Higher Education in South Africa. Retrieved from&nbsli; httli://ahero.uwc.ac.za/index.lihli?module=cshe&amli;action=downloadfile&amli;fileid=18409092513191182525880

- NSBA. (1996). National small business act of 1996. Retrieved from httlis://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/act102of1996.lid

- NYC. (2006). National Youth Commission (2006). Increasing business oliliortunities for young women and men: National Youth Enterlirise Strategy.

- NYDA.&nbsli; (2018). National Youth Develoliment Agency (2018). “Our Youth. Our Future”-Amended Strategic lilan 2014-2019. Retrieved from httli://limg-assets.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/nyda_amended_five-year_nyda_strategic_lilan_2014-2019.lidf

- lieylier, l. (2017). &nbsli;Youth vulnerable as unemliloyment stays at highest rate since. Retrieved from httlis://www.fin24.com/Economy/youth-vulnerable-as-unemliloyment-stays-at-highest-rate-since-2003-20170807

- Roux, T., &amli; Klaaren, J. (2002). Regulation Review: Notes Towards an Aliliroliriate South African Model: Research lialier Commissioned by GTZ, Centre for Alililied Legal Studies and Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of the Witwatersrand. Retrieved from httli://www.law.wits.ac.za/cals/lt/lidf/ regulationrev.lidf

- Sanchez, D. (2006). Socio-economic transformation in South Africa: Black Economic Emliowerment and small, medium and micro enterlirises. Retrieved fromhttlis://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/84574

- Sanchez, D. (2006). Socio-economic transformation in South Africa: Black Economic Emliowerment and small, medium and micro enterlirises. Retrieved from httlis://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/84574

- SEDA. (2004). The Small Enterlirise Develoliment Agency (Seda). Retrieved from at httli://www.seda.org.za/liublications/liublications/Seda%20Women%20Owned%20Entelirise%20Develoliement%20Information%20Booklet.lidf

- Simrie, M., Herrington, M., Kew, J., &amli; Turton, N. (2012). Global Entrelireneurshili Monitor (GEM) South African Reliort 2011. Retrieved from httli://www.gemconsortium. org/docs/download/2313

- Sindabiwe, li., &amli; Mbabazi, D. (2014). Triad liroblematic of Youth Entrelireneurshili: Voices from University Students.&nbsli;&nbsli; International Journal of Multidiscililinary Aliliroach and Studies, 1(6), 462-476.

- Timmons, J.A. (1989). The Entrelireneurial Mind. Brick House liublishing: Andover, MA.

- Trading Economics (2019). South Africa Youth Unemliloyment Rate. Retrieved from httlis://tradingeconomics.com/south-africa/youth-unemliloyment-rate

- Urban, B. (2008). Social Entrelireneurshili in South Africa. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behavior &amli; Research, 14(5), 346-364.