Review Article: 2024 Vol: 28 Issue: 2

Agri-Ecotourism giving New Dimension to Rural Marketing and Economic Advancement

Jolly Masih, BML Munjal University, Gurugram, Haryana

Mohit Sharma, Dr. Rajendra Prasad Central Agricultural University, Pusa, Bihar

Neha Saini, Capacity Building Facilitator in Food and Agribusiness

Ashish Sharma, Entrepreneur in Sustainability & Healthcare Innovation, New Brunswick, New Jersey

Citation Information: Masih, J., Sharma, M., Saini, N., Sharma, A. (2024). Agri-ecotourism giving new dimension to rural marketing and economic advancement. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 28(2), 1-10.

Abstract

Purpose – This research article investigated the potential of agri-ecotourism as a transformative force for revival of rural marketing and the rural economy in India. The study underscored the significance of strategic planning, community involvement, and policy backing to harness the untapped potential of agri-ecotourism. The research focused on the intricate dynamics between farmers and tourists, including both domestic and international visitors, with the primary aim of establishing a sustainable framework for agri-ecotourism in India, which had the potential to enhance rural marketing. Agri-ecotourism, blending agriculture with eco-conscious tourism, formed the core of this multifaceted study. Design/methodology- It employed a comprehensive well-structured Questionnaire based-approach, incorporating insights from case studies, fieldwork, and interviews with stakeholders to assess the opportunities and challenges arising from India's diverse agricultural and ecological landscape for sustainable rural development. Cluster analysis added a quantitative dimension to the qualitative data collected through case studies and interviews, enhancing the robustness and depth of the research findings. Findings – It sought to understand the expectations of domestic and international tourists in agri-ecotourism ventures, showcasing India's cultural and rural heritage to a global audience. Furthermore, the research acknowledged the crucial role of rural marketing within the agri-ecotourism context. It highlighted that the success of agri-ecotourism initiatives depended on effective marketing strategies that connected agrarian communities with the tourist market. Practical implications –This involved tailored approaches to promote local products, cultural experiences, and sustainable agricultural practices, thereby attracting tourists while ensuring equitable economic benefits for rural stakeholders. In conclusion, agri-ecotourism not only boosted rural economies but also necessitated innovative rural marketing strategies to fully realize its socio-economic advantages.

Keywords

Agri-Ecotourism, Sustainable Tourism, Rural Marketing, Rural Economy, Cluster Analysis.

Introduction

The transformative potential of agri-ecotourism, its impact on rural marketing, and the rural economy were considered noteworthy. Rural marketing involved the process of promoting and selling products or services in rural areas. Agri-ecotourism could significantly contribute to the development of rural marketing in India by creating new avenues for local farmers and artisans to market their products. Through agri-ecotourism ventures, farmers could showcase their agricultural produce, traditional handicrafts, and locally made products to tourists, thereby expanding their market reach and increasing sales (Ahire, et al., 2018). This not only bolstered the rural economy by generating additional income for farmers but also encouraged entrepreneurship and innovation in rural communities (Ali, et al., 2019).

Furthermore, agri-ecotourism contributed to the overall rural economy by creating employment opportunities. As tourists flocked to rural areas to experience the charm of agrarian life, there was a growing demand for hospitality services, guided tours, transportation, and other support services. This surge in demand led to job creation, especially for residents, reducing rural unemployment and boosting income levels (Barbieri & Streifeneder, 2019).

The integration of agri-ecotourism with pre-established tourist circuits, as proposed in this study, enhanced the economic prospects of rural areas. Tourists exploring agri-ecotourist circuits spent money on accommodations, food, transportation, and souvenirs, injecting capital into local businesses and communities (Barbieri, et al., 2019). This influx of tourism-related revenue could contribute to the overall development of rural marketing infrastructure and services, improving the living standards of rural residents (Bhatta, et al., 2019).

However, despite its potential, agri-ecotourism in India remained in its nascent stage, with limited and fragmented literature on its development (Boučková, 2008). Successful agri-ecotourism destinations required a deep understanding of tourist expectations and, at the same time, re-orientation of the tour packages (Bowler, et al., 2016). To address this gap, this study focused on understanding tourist behaviour and designing agri-eco circuits in rural India, tailored for nature and farm enthusiast tourists (Broccardo, et al., 2017).

An agri-ecotourism venture not only offered a unique and sustainable tourism experience but also had a significant impact on rural marketing and the rural economy (Cheung & Jim, 2014). ). It empowered local farmers, artisans, and entrepreneurs to expand their market reach, generated employment opportunities, and stimulated economic growth in rural areas. Therefore, fostering agri-ecotourism could boost rural marketing and could be a promising strategy for the development of the rural economy.

Literature Review

Agri-ecotourism, an amalgamation of agriculture, ecology, and tourism, gained prominence in India as a catalyst for rural development and marketing. This review explored the core concepts, trends, challenges, and potential within the context of agri-ecotourism and its implications for rural marketing in the country, which could be replicated across other developing countries with customized variations in research design (Cheung & Jim, 2014).

Conceptual Foundations: Agri-ecotourism integrated agriculture, natural environments, culture, and hospitality, offering tourists immersive rural experiences (Chi, et al., 2010). It emphasized the fusion of cultural and natural elements to create sustainable and engaging tourism (Cunningham & Sagas, 2006).

Growth and Trends: Agri-ecotourism was on the rise in India, aligning with global preferences for authentic and sustainable travel experiences (Demonja & Bacac, 2012). States like Kerala, Rajasthan, Himachal Pradesh, and Maharashtra witnessed a surge in agri-ecotourism activities (Rilla, et., 2013). Although COVID-19 severely impacted this industry, the future prospects were quite high.

Economic and Social Impacts: Agri-ecotourism provided rural communities with income diversification opportunities (Fatima, et., 2017). It stimulated local economies, generated employment, and preserved traditional cultures, crafts, and farming practices (Fleischer, et., 2018).

Environmental Conservation: A cornerstone of agri-ecotourism was the preservation of the natural environment. It promoted sustainable farming practices, biodiversity conservation, and responsible tourism (Fleischer & Tchetchik, 2005). Agri-ecotourism served as an educational tool, enlightening tourists about the importance of environmental stewardship and sustainable agriculture (Gartner, 2005).

The future of agri-ecotourism in India looked promising, especially as tourists sought meaningful and sustainable travel experiences. Another significant association with the Indian quest to be a developed nation, which ultimately created the necessity of such nature-based ventures. Rural regions, rich in agricultural heritage and cultural diversity, were well-suited to become agri-ecotourism hubs. However, addressing infrastructure issues, enhancing community involvement, and formulating clear policies were pivotal for sector growth and sustainability. Further research could deepen our understanding of agri-ecotourism's role in rural marketing and its impact on diverse Indian contexts.

Methodology

This section outlined the methodology employed in the study, including the study area, data collection tool, sample size determination, data curation, and training.

Study Area: The study focused on Rajasthan, India - a prominent tourist destination, selected for its diverse climatic variations, cultural heritage, archaeological wonders, and wildlife. The specific districts chosen were Jaipur, Bikaner, and Jaisalmer (Govindasamy & Kelley, 2014).

Data Collection Tool: A survey instrument was meticulously developed and pretested based on literature and expert consultations, covering variables related to tourist expectations for agri-ecotourism activities. Qualitative variables were selected for the research questionnaire, assessed on a 5-point Likert scale (GRAM, 2016). Detailed insights were incorporated from relevant case studies, fieldwork, and interviews with stakeholders to assess the opportunities and challenges arising from India's diverse agricultural and ecological landscape for sustainable rural development.

Sample Size: Despite the lack of a precise population size of tourists visiting agri-eco destinations in Rajasthan and farmers adopting agri-ecotourism, the study considered that over 1 million visitors annually would require a sample size exceeding 100 with up to a +/- 90% confidence interval. The sample size was determined to be greater than 100, with 120 tourists (Hatan, et al., 2021).

Data Curation and Training: Data underwent curation and training to check for normality and missing values using SPSS version 25.0. The data was found to be normally distributed with no missing values (Heyder, et al.,2010).

Cluster Analysis: To distinguish between domestic and foreign tourist expectations, a two-stage cluster analysis was performed on the 120 respondents using R studio software (viz_cluster package). This method aimed to identify distinct classes or groups of tourists based on their behavior. The number of clusters and goodness of fit were determined using AIC (Akaike's Information Criterion) (Masih & Rajasekaran, 2020). Cluster analysis revealed groups with significantly different characteristics (Nidhi, et al.,2017).

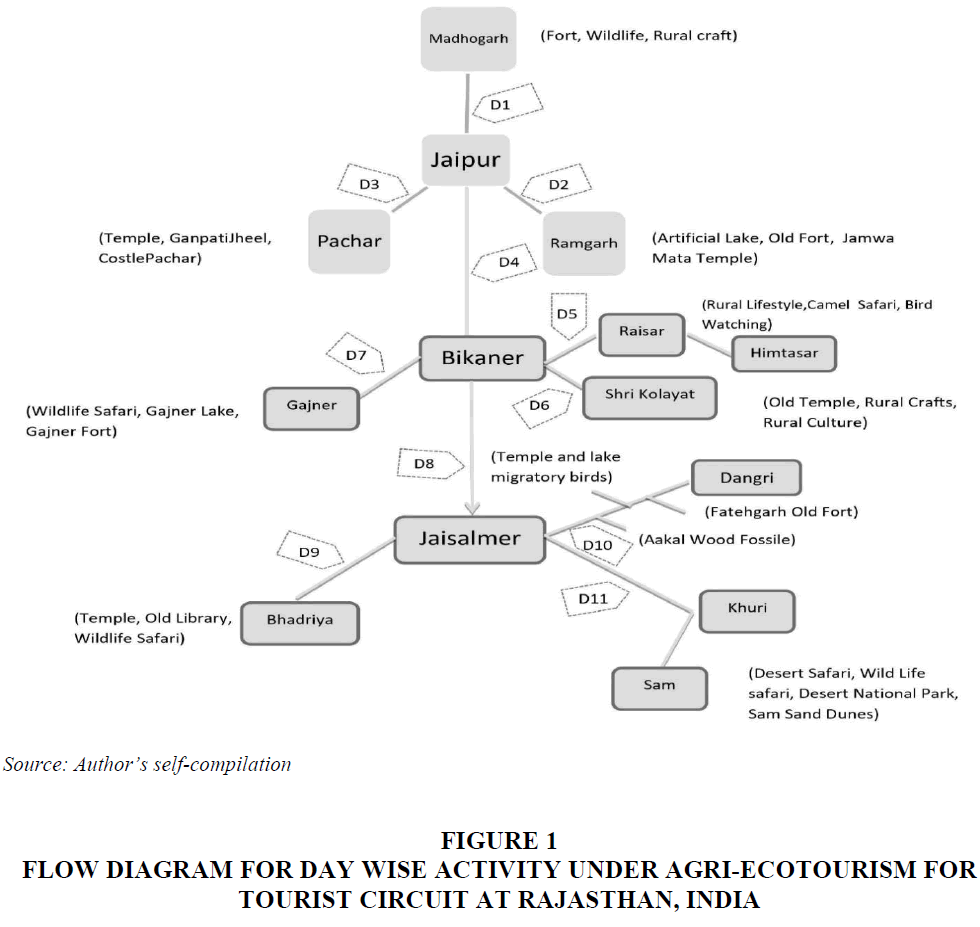

This methodology allowed for a comprehensive assessment of tourist perspectives in the context of agri-ecotourism in Rajasthan, India Figure 1.

Figure 1 Flow Diagram for Day Wise Activity Under Agri-Ecotourism for Tourist Circuit at Rajasthan, India

Results

Based on the survey findings, a suitable tourist circuit connecting the study areas was identified.

This diagram represented an '11-day package program' for the tourists (domestics and foreign) to promote rural marketing through the concept of agri-ecotourism. It covered the desert circuit of Rajasthan state and included all components for agri-ecotourism. Area-wise details along with particular agri-eco tour activity were also mentioned in the flow diagram. This was one of the novel findings of the study that could help policy makers develop agri-eco tour packages in the identified areas (Ali, et al. 2019).

To further dig into the insights of the analysis, researchers adopted a two-step cluster analysis approach (Figure 2). A two-step cluster analysis was applied to the data collected from the primary survey (Masih, et al., 2017). In this research, the author sought to identify clear groupings that were large enough in size to have management implications, yet not too large to obscure differences between respondents (Masih & Rajasekaran, 2020).

Figure 2 revealed the likelihood of two things; first, there were distinct clusters present in the sample dataset, and secondly, the statistical significance of the results obtained (Bowler, et al., 2016). The AIC method represented coefficients that ranged from – 1.0 to +1.0. However, for all practical purposes, a coefficient that ranged from -0.5 to +1.0 was considered acceptable and a good solution. The AIC method established that there were two distinct clusters. There was also 'fair' cohesion within the obtained clusters and 'fair' difference between them. Figure 2 also represented the cluster distribution of 2 clusters (Heyder, et al.,2010). Findings of the study (see Table 1-4) talked about cluster distribution, where cluster 1 was named as "domestic tourist cluster," and cluster 2 was named as "foreign tourist cluster." The two clusters were named according to tourist distribution found in both clusters. Cluster 1 had the maximum Indian tourists and a few NRI (Non-Residential Indian tourists living in other countries), and cluster 2 had all the foreign tourists (Masih & Rajasekaran, 2020).

| Table 1 Cluster Profiling According to Residence Type of Cluster Members | |||

| Residence type | Frequency | ||

| Cluster 1 Domestic tourist | Cluster 2 Foreign tourist | Total | |

| Rural | 14 | 0 | 14 |

| Semi-urban | 18 | 0 | 18 |

| Urban | 31 | 23 | 54 |

| Metropolitan | 16 | 18 | 34 |

| Table 2 Cluster Profiling According to Country of Residence of Cluster Members | |||

| Country of residence | Frequency | ||

| Cluster 1 Domestic tourist | Cluster 2 Foreign tourist | Total | |

| India | 60 | 0 | 60 |

| Italy | 0 | 11 | 11 |

| France | 9 | 16 | 25 |

| UK | 0 | 9 | 9 |

| US | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| South Africa | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Singapore | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Table 3 Cluster Profiling According to Gender of Cluster Members | |||

| Gender | Frequency | ||

| Cluster 1 Domestic tourist | Cluster 2 Foreign tourist | Total | |

| Male | 46 | 18 | 64 |

| Female | 33 | 23 | 56 |

| Table 4 Clustering Centroid Mean and SD for both Clusters of Agri-Ecotourism | |||

| Cluster Centroid Mean (SD) | |||

| Cluster 1 Domestic tourist | Cluster 2 Foreign tourist | Combined | |

| Entertainment value | 4.48 (0.71) | 3.95 (1.02) | 4.3 (0.87) |

| Water quality | 4.51 (0.58) | 4.8 (0.4) | 4.61 (0.54) |

| Onsite rest rooms | 4.29 (0.75) | 3.9 (0.58) | 4.16 (0.72) |

| Countryside accommodations | 4.46 (0.55) | 3.39 (0.89) | 4.09 (0.85) |

| Educational value | 4.43 (0.69) | 3.76 (1.22) | 4.2 (0.96) |

| Attractive location | 4.58 (0.55) | 3.98 (0.91) | 4.38 (0.75) |

| Comfort of interaction with service providers | 4.28 (0.97) | 2.54 (0.64) | 3.68 (1.20) |

| Purchasing opportunities | 4.35 (0.77) | 4.2 (0.68) | 4.3 (0.74) |

| Security and trust | 4.62 (0.54) | 4.41 (0.63) | 4.55 (0.58) |

| Interpersonal congruency | 4.59 (0.74) | 3.07 (1.19) | 4.08 (1.17) |

| Participate in local festivals | 4.54 (0.69) | 4.41 (0.50) | 4.5 (0.64) |

| Interact with rural people and learning local languages | 4.65 (0.62) | 4.54 (0.55) | 4.61 (0.60) |

| Convenient location | 4.56 (0.64) | 4.27 (0.90) | 4.46 (0.74) |

| Adequate parking | 4.34 (1.04) | 2.88 (0.87) | 3.84 (1.20) |

| Luxurious accommodations | 4.1 (0.97) | 2.68 (1.01) | 3.62 (1.19) |

It was observed that the cluster of domestic tourists mainly belonged to semi-urban, urban, and metropolitan areas. Domestic tourists from rural areas were minimal, since rural tourists already knew much about agri-ecotourism, and they had less financial capacity to spend on tourism compared to tourists in urban and semi-urban areas. In the case of cluster 2 of foreign tourists, all the respondents were from urban and metropolitan areas, thus displaying their greater financial capacity to spend on travel and tourism (Cunningham & Sagas, 2006).

It was clear by the formation of both clusters that cluster 1 mainly consisted of Indian tourists and some Non-Residential Indians (NRI) living in other countries, while cluster 2 mainly consisted of all the foreign tourists and no Indian tourists. The clarity of both clusters increased the reliability of the analysis (Govindasamy & Kelley, 2014).

Cluster 1 of domestic tourists had a higher frequency of males (71.9%), while cluster 2 of foreign tourists had nearly an equal ratio of males (58.9%) and females (41.1%) (Gartner, 2005).

In the context of rural marketing, these findings offered valuable insights into tailoring marketing strategies for agri-ecotourism ventures catering to both domestic and foreign tourists.

For Cluster 1-Domestic Tourist, the emphasis on "interacting with rural people" and "learning local languages" underscored the importance of promoting authentic cultural experiences. Marketing efforts should have highlighted opportunities for tourists to engage with local communities and immerse themselves in the cultural aspects of rural destinations. Emphasizing "security and trust" could have involved showcasing safety measures, certifications, and testimonials to instill confidence in domestic tourists. "Attractive location" should have been visually showcased through marketing materials, while "interpersonal congruency" suggested the need for friendly and accommodating staff (Demonja & Bacac, 2012).

The positive attitude toward factors such as "entertainment value," "water quality," and "educational value" should have been leveraged to communicate a well-rounded and enriching agri-ecotourism experience. "Adequate parking and purchasing opportunities" could have been highlighted as added conveniences. Moreover, emphasizing the "value for money" aspect aligned with domestic tourists' preferences, necessitating transparent pricing and the demonstration of tangible value (Cheung & Jim, 2014).

For Cluster 2-Foreign Tourist, the focus on "clean water" underscored the importance of emphasizing hygiene and sanitation measures in marketing materials. Addressing health concerns, especially for waterborne diseases, was crucial to instill confidence in foreign tourists. "Entertainment value" and "participation in local festivals" should have been marketed to highlight the cultural experiences unique to rural destinations. "Convenient location" should have been showcased for its accessibility (Barbieri, et al., 2019).

Lastly, recognizing that foreign tourists were willing to spend extra for adventure and memorable experiences, marketing strategies should have emphasized the extraordinary and transformative nature of the agri-ecotourism offerings. Highlighting the opportunity for once-in-a-lifetime experiences and memorable encounters with rural communities could have resonated strongly with this audience (Masih & Rajasekaran, 2020).

Such understanding about the distinct preferences of domestic and foreign tourists within the context of agri-ecotourism allowed for targeted rural marketing strategies by Destination Marketing Organizations (DMOs) that catered to their specific needs and expectations, ultimately enhancing the appeal and success of such ventures (Barbieri & Streifeneder, 2019).

Discussion

The past research delved into the intricate dynamics of agri-ecotourism in various regions of Rajasthan, India, scrutinizing both the demand from domestic and foreign tourists and the supply forces represented by local farmers. While the state government had made commendable strides in promoting agri-ecotourism, significant challenges persisted on the path to its widespread adoption (Hatan, et al., 2021).

Furthermore, this study emphasized that the motivations for diversifying into agri-ecotourism extended beyond revenue generation, encompassing the promotion of the holistic benefits of rural India, including fresh produce, local attractions, and handicrafts. It suggested leveraging local brand ambassadors and creative branding strategies to enhance awareness and adoption of agri-ecotourism at the village level (Heyder, et al.,2010).

The research also scrutinized tourists' expectations, identifying factors crucial for both domestic and foreign visitors. Domestic tourists sought interaction with service providers, security, cleanliness, quality food, and engagement in farm activities. Meanwhile, foreign tourists were drawn to India's rich culture, traditions, and unique festivals, emphasizing the importance of offering authentic ethnic foods (Masih & Rajasekaran, 2020).

However, foreign tourists also expressed concerns about safety, hygiene, and tourist services in India, which could have jeopardized the success of agri-ecotourism ventures. Addressing these issues was pivotal for sustaining the appeal of rural tourism and for boosting rural marketing (Nidhi, et al.,2017). The findings of this study could also be applied to various Indian states and South-East Asian countries like Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines.

This research underscored the immense potential of agri-ecotourism as a means to promote rural marketing and preserve the cultural heritage of rural India. However, to fully harness this potential, it called for a concerted effort to address challenges, ensure safety and quality, and facilitate coordinated development efforts among relevant stakeholders (Masih & Rajasekaran, 2020).

Conclusion

The study's findings had promising implications for rural marketing, extending beyond Rajasthan to various Indian states and South-East Asian countries like Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines. They could guide the creation of tourist circuits closely tied to rural communities. Future research should also have covered the farmers' level strategy on farm diversification with eutopia model components. Understanding tourists' motivations for choosing agri-ecotours was crucial, enabling tailored packages to suit different budgets and durations. Effective planning and strategy were essential for economically viable, socially responsible, and ecologically sustainable agri-ecotourism, enhancing the visitor experience and promoting sustainable rural marketing practices in this growing industry.

References

Ahire, L.M.; Srinivasarao, C.; Kumar, S.V.; Reddy, V. (2018). An Innovative Concept to Earn an Extra Income from Agri Tourism-The Case of an Agri-Tourism Centres in Maharashtra, India. Int. Ref. Peer Rev. Index. Q. J. Sci. Agric. Eng., 7, 63–67.

Ali, M., Puah, C. H., Ayob, N., & Raza, S. A. (2019). Factors influencing tourist’s satisfaction, loyalty and word of mouth in selection of local foods in Pakistan. British Food Journal. Vol. 122 No. 6, pp. 2021-2043.

Barbieri, C., & Streifeneder, T. (2019). Agritourism advances around the globe: A commentary from the editors. Open Agriculture, 4(1), 712-714.

Barbieri, C., Sotomayor, S., & Aguilar, F. X. (2019). Perceived benefits of agricultural lands offering agritourism. Tourism Planning & Development, 16(1), 43-60.

Bhatta, K., Itagaki, K., & Ohe, Y. (2019). Determinant factors of farmers’ willingness to start agritourism in rural Nepal. Open Agriculture, 4(1), 431-445.

Boucková B. (2008) Definition of Agritourism. AgroTourNet ‘S Hertogen Bosch 2008. vaiable from: www.agrotournet.tringos.eu/files/definition_of_agritourism.ppt on 12/02/2020

Bowler, I., Clark, G., Crockett, A., Ilbery, B., & Shaw, A. (2016). The development of alternative farm enterprises: a study of family labour farms in the Northern Pennines of England. Journal of Rural studies, 12(3), 285-295.

Broccardo, L., Culasso, F., & Truant, E. (2017). Unlocking value creation using an agritourism business model. Sustainability, 9(9), 1618.

Cheung, L. T., & Jim, C. Y. (2014). Expectations and willingness-to-pay for ecotourism services in Hong Kong’s conservation areas. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 21(2), 149-159.

Chi C. G., Abkarim S. & Dogan G., (2010), Examining the Relationship Between Food Image and Tourists’ Behavioral Intentions, http://www.eurochrie2010.nl/publications/15.pdf accessed 19/1/20 Development, The Open Social Science Journal, Issue 3, pp- 41-50

Cunningham, G. B., & Sagas, M. (2006). The Role of Perceived Demographic Dissimilarity and Interaction in Customer-Service Satisfaction 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36(7), 1654-1673.

Demonja, D., & Bacac, R. (2012). Agritourism development in Croatia. Studies in Physical Culture & Tourism, 18(4).

Ellen Rilla, Shermain D. Hardesty, Christy Getz & Holly A. George, (2011), California Agri ecotourism operations and their economic potential are growing, California Agriculture 65(2):57-65. DOI: 10.3733/ca.v 065n02p57. April-June 2011.

Fatima, J. K., Khan, H. Z., & Halabi, A. K. (2017). Ecotourism Participation Intention in Australia: Mediating Influence of Social Interactions. Tourism Analysis, 22(1), 85-91.

Fleischer, A., Tchetchik, A., Bar-Nahum, Z., & Talev, E. (2018). Is agriculture important to agritourism? The agritourism attraction market in Israel. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 45(2), 273-296.

Fleischer, A., & Tchetchik, A. (2005). Does rural tourism benefit from agriculture? Tourism Management, 26(4), 493e501.

Gartner, W. C. (2005). A perspective on rural tourism development. Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy, 35(1100-2016-89740).

Govindasamy, R., & Kelley, K. (2014). Agritourism consumers’ participation in wine tasting events: An econometric analysis. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 26(2), 120–138. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWBR-04-2013-0011

GRAM (Global Rajasthan Agro Meet), 2016 extracted at http://www.gramrajasthan.in/assets/images/pdf/The_Event_That_Was.pdf accessed on 20/02/2020.

Hatan, S., Fleischer, A., & Tchetchik, A. (2021). Economic valuation of cultural ecosystem services: The case of landscape aesthetics in the agritourism market. Ecological Economics, 184, 107005.

Heyder, M., Hollmann-Hespos, T., & Theuvsen, L. (2010). Agribusiness firm reactions to regulations: the case of investments in traceability systemsh. International journal on food system dynamics, 2, 133-142.

Masih, J., & Rajasekaran, R. (2020). Integrating big data practices in agriculture. IoT and Analytics for Agriculture, 1-26.

Masih, Jolly, Amita Sharma, Leena Patel, and Shruthi Gade. Indicators of Food Security in Various Economies of World. J. Agr. Sci 9, no. 3 (2017): 254.

Nidhi, R., Jolly, M., & Gadhe, S. (2017). Study of Agri-Clinics & Agri-Business Centres for Improving Women Farmers' Access to Extension Services in Agriculture. Indian Journal of Extension Education, 53(3), 67-71.

Received: 11-Sep-2023, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-13993; Editor assigned: 12-Sep-2023, PreQC No. AMSJ-23-13993(PQ); Reviewed: 30-Oct-2023, QC No. AMSJ-23-13993; Revised: 29-Dec-2023, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-13993(R); Published: 18-Jan-2024