Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 5

Agency Theory and the Jordanian Corporate Environment: Why A Single Theory is Not Enough

Zaid Saidat, Queen Margaret University

Zaid Saidat, Queen Margaret University

Lara Al-Haddad, Yarmouk University

Dina alkhodary, Middle East University

Abstract

This article seeks to determine how useful corporate governance theories are in understanding the business environment in Jordan, and the context of concentrated ownership which exists. As with most developing countries, a majority of firms are controlled by a few shareholders, overwhelmingly families, which has a major impact on company management and operations. This study contends that traditional agency theory is not able to clearly explain many practice of corporate governance as it does not take into account social and cultural issues. A review of several corporate governance theories (agency theory, stewardship theory, stakeholder theory, resource dependency theory and institutional theory) is undertaken in this article analysing how these theories address the impact of governance mechanisms, such as board members, and their social relationships. Whilst each theory, on its own, has different weaknesses, collectively they are able to complement one another.

Keywords

Corporate Governance, Theory, Implications, Jordan.

Introduction

Corporate governance is now an important focus of interest within the business community and academic research (Bebchuk, 2009). The collapse of companies such as, Arthur Andersen, WorldCom and Tyco gave rise to greater concern globally for corporate governance (Solomon & Solomon, 2004). Corporate scandals, such as Enron, resulted in the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act 2002, to restore the confidence of investors. Similarly, in the UK, corporate failures, such as Maxwell Group and BCCI, provoked major alterations to British corporate governance by government (Pickett, 2007). The 1997 financial markets crisis caused great concern in governments and business as well as corporate bankruptcies (Tarraf, 2010). This has all lead to the current situation where good corporate governance is seen as fundamental to improve economic growth and corporate performance, uphold investor rights and fortifies investment environments (Arnold & De Lange, 2004; Price et al., 2011). This need to improve corporate performance has lead a growth in research and the development of a variety of theories in the corporate governance field. Such theories offer a theoretical structure to understand corporate governance from diverse perspectives. Significant difference in theories may be due to differing perspectives on company goals (Al-Wasmi, 2011). For example, agency theory states the company's goal is to maximize shareholders' wealth, however, stakeholder theory argues that the company needs to take account of all stakeholders.

As with other Arab countries, Jordan, struggles with systemic inefficiencies, including an inadequate system of protection for the rights of investors (Al-Haddad et al., 2011). Furthermore, Jordan's framework of corporate governance varies from Western business environments, such as the US and UK. For instance, Jordanian companies are characterised by family, individual group and government ownership (Al-Muhtaseb, 2009; Al-Amarneh, 2014). Given this divergence from the West, there is an onus on researchers and policymakers to comprehend and advise on the applicability and adaptability of corporate governance theories for the Jordanian corporate environment.

Corporate Governance Theories

A theory may be described as, “a coherent set of hypothetical, conceptual and pragmatic principles forming the general framework of reference for a field of inquiry” (Hendriksen, 1970, p. 1). To fully appreciate corporate governance, a theoretical framework is required. Ziolkowski (2005, pp. 357-358) contends:

“Corporate governance research should be no different from scholarly enquiries in natural sciences in terms of methodological approach. Such research requires that corporate governance scholars place the subjective process of developing ideas into a logical framework of challenge and questioning through debate and data collection. This is a continuous process starting with conceptual and propositional analysis for defining terms, model building and theory development.”

Multiple theories have been developed to express the actual mechanisms of corporate governance. However, there is no one theory alone which is able to explain every aspect and practice of corporate governance (Clarke, 2004). So, each theory suffers multiple weaknesses (Chen & Roberts, 2010), yet, in collaboration provide an increased understanding. This ie especially true for corporate governance as a multi-faceted issue, spanning many areas, such as, economics, finance, management, policy and ethics (Solomon, 2010). Due to this, it is unwise to depend on a single theory, as agency theory (Sharma, 2013) and the most prudent course of action is to field several different theoretical frameworks to comprehend corporate governance. Any theory or range of theories must take into account social, economic and political impacts on corporate governance practice, which are fundamental to understanding corporate governance generally and in specific country and regional contexts (Al Wasmi, 2011). There may be a closer alignment of certain theories with the business practices of specific countries in terms of their economic and political situation or their cultural values (Mallin, 2007).

Different theories have been constructed which focus on different aspects of corporate governance. The theories which are dominant and most frequently used are agency theory, stewardship theory, stakeholder theory, resource dependency theory and institutional theory (Blair, 1995; Davis et al., 1997; Donaldson & Preston, 1995; Eisenhardt, 1989; Fama & Jensen, 1983; Freeman, 1999; Jensen & Meckling, 1976; Watts & Zimmerman, 1986). Both agency and stewardship theory have a greater concentration on the actions and motivations of managers, whilst stakeholder and institutional theory prioritise the centrality of social relationships over the structure of businesses (Al Mamun et al., 2013). Resource dependency theory comes from yet another viewpoint on how businesses access the resources required for their survival (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978). There follows a review of key theories, chosen for their ability to interpret the relationships within corporate governance and corporate performance.

Agency Theory

Principal–Agent Conflicts (Type I Agency Problem)

A wide distribution of ownership characterises the modern corporation, especially publicly held companies, where decision making is devolved to a management group, which runs the company separately from owners. Berle ^ Means (1932) most clearly identified this modern structure where the wider distribution of shareholding divorced ownership from control in the United States. However, such phenomena were already debated by Adam Smith (1776) more than two centuries before, as quoted in Marks (1987):

“The directors of such companies (joint stock companies) ... being the managers rather of other people’s money than of their own, it cannot well be expected that they should watch over it with the same anxious vigilance with which the partners in a private co-partner frequently watch over their own ... Negligence and profusion, therefore, must always prevail, more or less, in the management of the affairs of such a company.” (Book 5, Chapter 1, Part 3, Art. 1)

Nowadays, the interests of such companies (public corporations) are often associated with the study by Jensen & Meckling (1976) is considered a fundamental study of agency relationship in the separation of ownership and control in modern corporations. They describe the contractual relationship between shareholders “principals” and managers “agents”, agents delegated to carry out services within and for the company in the interests of the principals. The roles do lead to differing aims of agents than their principals, and the potential for conflict of interest. For agency theory, there are assumptions by shareholders that managers or board members will make decisions and act in the best interests of shareholders; however this is not necessarily the case (Padilla, 2002). Such deviation from the contractually agreed relationship leads to problems of agency.

Such is the fundamental premise of agency theory that due to the conflicts of interest between agents and principals a problem of agency arises (Fama & Jensen, 1983; Jensen & Meckling, 1976). There can be many causes of such conflicts of interest in corporations, for example: (1) managers may aim to maximise their own benefits instead of promoting shareholder value (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). This may be compounded by poor monitoring of management by shareholders, which is likely to occur when the incentives for tasks such as monitoring are limited among a widely dispersed group of shareholders. Managers are able to exploit such conditions to prioritise their own interests (Hart, 1995); (2) managers are focused on low-risk investments and reduced trading on equity, lessening the risk of bankruptcy and damage to capital management and portfolio (Denis, 2001).; (3) free cash created by a business frequently produces major conflicts between managers and shareholders. For instance, shareholders can achieve free cash flow through both share and repurchases, however, managers favour investing free cash flow in negative net present value (NPV) projects or using it to expand the company with new projects rather than simply handing it over to shareholders (Denis, 2001). Grant (2003) contends that the first aim of principals is to maximise value of their own interest, whereas the primary aim of agents is development of the company; business success positively reflects on management and their remuneration packages and well as general prestige associated with company size and success; (4) ineffective contracts between shareholders and managers may easily create significant agency problems (Fama & Jensen, 1983).

Agents probably have the best understanding of the day to day running of the business, as well as action planning and potential future outcomes (Ross, 1973). Such an imbalance in access to information leads to unavoidable agency problems due to moral hazard and adverse selection. Moral hazard stems from an imbalance of information between principals and agents. Meanwhile, adverse selection results from the dissatisfaction of the principal in the agent they initially selected, over time it is clear the agent is not achieving what is required by the company.

Jensen & Meckling (1976) highlighted that actions by the principal to ensure compliance by the agent to the principal's interests have costs, such as, monitoring costs, bonding costs and residual loss, generally referred to as agency costs. Monitoring costs are incurred by shareholders to limit and shape the action of agents. Imbalances in information necessitate shareholders to increase monitoring costs and to increase the complexity of financial contracts. Such contracts can include extra costs for preparing trustworthy audits and accounting information, manager payments and potential costs for replacing executive managers and teams. Bonding costs, paid mainly as salary and bonuses, are expenses as an alternative to monitoring costs, paid directly to agents to induce the full sharing of company information to shareholders and actions by the agents which are bonded to the interests of the shareholders. Such precautionary payments still cannot ensure complete convergence of manager and shareholder interests. Residual loss is the cost of lessening the interest of the principal because of any mismatch of actions, and so increasing the self-interest of both the principal and the agent.

The detachment of ownership from control offers opportunities for managers to take part in exploiting the wealth of shareholders. For example, managers can increase their wealth by greater remuneration, increased bonuses or fraud. Previous literature on corporate performance and ownership structure seeks to stop the agency dilemma in companies with detached shareholders experiencing conflicts of interest with managers. Following this, Jensen & Meckling (1976) propose that stock ownership by managers promotes more manager incentive. Managers with significant ownership interest are incentivised to improve performance which can offer the opportunity to shareholders to reduce costs in terms of executive privileges.

Alternatively, Stulz (1988), Morck et al. (1988) and Denis & McConnell (2003) suggest that greater managerial ownership produces an entrenchment effect as it provides more voting power to innoculate managers from both internal and external control. Underperforming managers with large shareholdings are difficult to remove from their position. Different studies have found that it is important for the ownership structure of each organisation to be designed at the level which will best maximise profits (Demsetz, 1983; Demsetz & Lehn, 1985).

Furthermore, Shleifer & Vishny (1997) found that it is more likely for companies with a managerial structure separated from ownership structure to be profitable and perform well. In such a situation, the principals are strongly encouraged to control management behaviours, so protecting their investment and growing the company value. However, major shareholders can have considerable power over management actions and so use their position and company wealth to advantage themselves over other shareholders. Al-Ghamdi & Rhodes (2015) state that the key dilemma for these companies is that a concentrated ownership insider creates such a conflict of interest.

Principal–Principal Conflicts (Type II Agency Problem)

Many companies have concentrated ownership, in which case it is not possible to completely separate ownership and control and is generally characterised by a controlling shareholder. Controlling shareholders hold significant numbers of voting shares in a company, and effectively, have direct or indirect control of the policy and operations of a company. Dharwadkar et al. (2000) explain that the position of controlling shareholders encourages them to manage their interests actively and engage in decision making and the motoring of company operations, meaning they hold key company roles as board members or senior executives. Shleifer & Vishny (1997) and La Porta et al. (1999) describe a 5% to 50% owners of outstanding shares associated with voting rights as a “controlling shareholder”. Further, Wiwattanakantang (2001) suggest that it is also useful to define the proportion of control as regards to the legal and economic environment of any given country. Agency theory suggests that it in controlling shareholders interests to have command over managers, given their power to do so at minimal additional costs and the connection of their profit/loss to company performance.

Such active command should be of benefit to all shareholders (Holderness, 2003), however, when controlling shareholders pursue their own interests, they may be benefitting themselves at the expense of minority shareholders (Dharwadkar et al., 2000; Young et al., 2008). Benefits, like price transferring and personal needs, such as, business performance and career opportunities, dividends and reputation, (Hart, 1995). Such conflicts between different shareholder groups are principal–principal conflicts or agency problem type II. It is shown by Young et al. (2008) how this conflict is apparent when a majority shareholder, e.g. and individual or a family, has ownership and control. La Porta et al. (1998) propose that in a majority held firm the main conflict will be between the minority and the majority shareholders, as the majority shareholders seek to amass wealth at the expense of the minority shareholders.

Due to this dilemma, Agency theorists seek to

"Identify situations in which the principal and agent are likely to have conflicting goals and then describing the governance mechanisms that limit the agent’s self-serving behavior” (Eisenhardt, 1989, p.59).

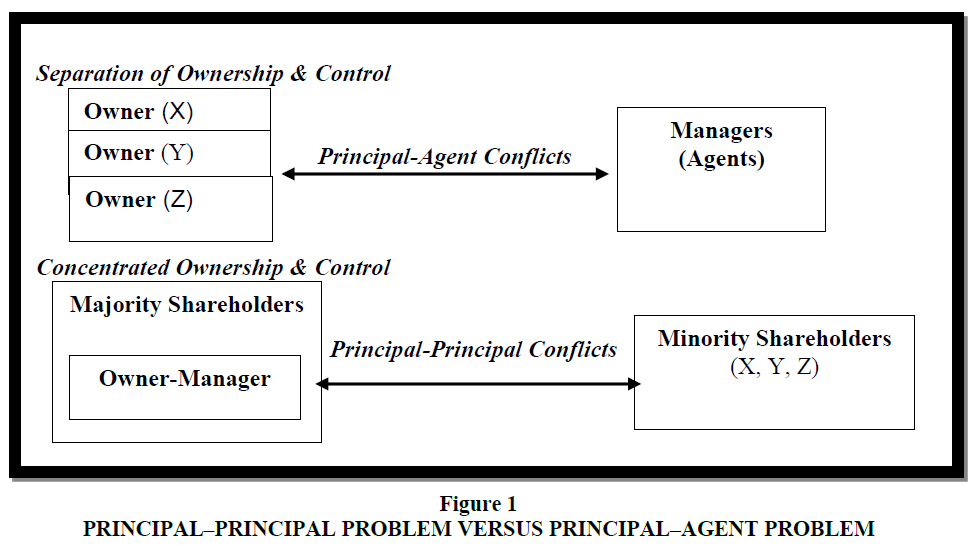

Fama & Jensen (1983) examined the importance of the role of directors in management oversight. Jensen & Meckling (1976) examined how the participation of managers in ownership supports the merging of managers' goals with owners. However, as seen, the agency problem of a concentrated ownership structure which exist in Jordan and in the Middle East more widely, is the family owned company, where a family group is the majority shareholder seeking their own interests at the expense of and in conflict minority shareholders. Figure 1, below, shows the difference between principal–agent conflict (type I agency conflict) and principal–principal conflict (type II agency conflict).

The upper part of the figure outlines how the main agency problem of separation of ownership and control is the principal–agent problem between a large number of small shareholders and the non-shareholding managers (agents). The lower part shows the agency problem of concentrated ownership as a principal–principal conflict, between a large number of minority shareholders and the controlling shareholders who promote or direct the activities of the company that benefit them but can harm minority shareholders causing conflict.

The problem of agency is a fundamental issue in corporate governance, agency issues between shareholders and managers or majority and minority shareholders. Homayoun and Homayoun (2015) discuss corporate governance as having a major role in minimising agency problems. Agency theory identifies that problems such as separation of ownership and control worsen when there is a limited corporate governance structure (Ongore & Kobonyo, 2011). In this way, corporate governance can be understood as a range of tools to protect owners from conflicts of interest with managers, which will decrease agency costs and incentivise agents to make decisions in line with the interest of shareholders, for instance, capital investments (Shleifer & Vishny, 1997; Fama & Jensen, 1983). The goal of corporate governance is to produce governance systems sufficient to improve the performance of the firm and to maximise wealth.

When seeking to minimise majority and minority shareholder conflict it is also possible to apply agency theory. Villalonga & Amit (2006) argue that such conflicts are common when a majority shareholder assumes a dominant position in the firm to take out benefits at the expense of other shareholders. The owners of a family firm may pursue family interests over shareholder interests generally, exercising supervision and control to maximise their own assets and wealth over others rather than promoting firm performance (Van den Berghe & Carchon, 2002). Therefore, the relationship and role of family firms and corporate governance impact family firm performance including ownership structure and firm decisions (Pindado & Requejo, 2015).

The most direct impact of agency theory is on issues of conflict where it can support different interests of different stakeholders in governance to be better aligned and identify potential conflicts and harm to firm performance in the long term (IFC 2011). Importantly, agency theory can support the process of improved decision making, prioritising balanced information sharing, efficient communication and a governance structure with clear roles and responsibilities. Overall, the application of agency theory can significantly improve long term firm performance (IFC, 2011).

Agency Theory and the Jordanian Corporate Environment

Reform in corporate governance has been key on the agenda of the Jordanian state in recent years and the Jordan Corporate Governance Code (JCGC) of 2009 represents the foundation of reform. The JCGC aims to minimise manager and shareholder agency conflicts and to develop the transparency and accountability of boards of directors (Ibrahim & Hanefah, 2016), which is very important in Jordanian listed firms where there is high ownership concentration (ROSC Jordan, 2004). This high ownership concentration produces conflict between small and large shareholders because it is detrimental to small shareholders (Baydoun et al., 2013). Owning large amounts of shares gives them the power to appoint directors and they can choose to appoint people who will work on their behalf, in their interests, including their friends or relatives. Also they commonly make appointments based on favouritism or returning favours, which again goes against the rights and interests of small shareholders (Al-Jazi, 2007). Furthermore, a very large number of Jordanian companies are family firms, and the large family shareholders can operate to develop voting power bases, control managers’ actions through self-interested policy making, harming firm performance and creating significant problems of agency. At the same time, the concentrated power of family shareholders can lead to a closer monitoring of management decisions in their own interests. These practices harm financial performance, which makes it very important to understand and develop an agency theoretical framework for the Jordanian corporate context.

Stewardship Theory

Stewardship theory differs from agency theory as it depends on the premise that managers are motivated to act in the interests of shareholders and not their own interests (Davis et al., 1997). This suggests that giving a more complete control to managers is the best solution for shareholders, resources allocation and firm performance (Letza et al., 2004). Stewardship theory is based on a a range of behavioural assumptions for senior managers. It assumes that the interests of agents are in line with owner objectives (Davis et al., 1997). That managers are trustworthy, therefore amalgamating the positions of chairman and CEO is an effective corporate governance practice (Donaldson & Davis, 1991). Further, it assumes that managers have best access to information and company knowledge so have the best abilities in decision making (Donaldson & Davis, 1994) and will utilise resources most effectively to increase firm performance and value (Davis et al., 1997), underpinned by fear of failure and loss of reputation (Conyon & He, 2011).

There is a key difference between stewardship and agency theory around an assumption of trust rather than an assumption of conflict (Donaldson & Davis, 1991, Manawaduge, 2012). This clearly offers an important contribution as a counterbalancing concept for the development of a broader theoretical structure to understand and strengthen corporate governance.

Stewardship Theory and the Jordanian Corporate Environment

The position of the JCGC is for the positions of CEO and chairperson to be separate and places importance on the placement of non-executive directors and one third independent directors on the board. JCGC seeks to improve corporate governance through better managerial oversight and monitoring which goes against stewardship theory, which highlights trust in management over strong supervision of performance. In its own way the high level of family ownership in the Jordanian corporate context may support or fulfil this assumption of trustworthiness when family owners frequently apppoint close allies such as friends and relatives as directors (Siebels and Knyphausen-Aufseb, 2012).

Stakeholder Theory

Stakeholder theory arose as a critique of the shareholder model in the 1970s (Sternberg, 1997), where stakeholders are defined as any group or individual who may impact a corporation (Freeman, 1984). Such a broad definition means that a wide range of participants might be considered as stakeholders, both direct and indirect involvement (Carroll & Buchholtz, 2003). This can be taken to include customers, employees, shareholders, suppliers, creditors and communities in proximity to company activities, right up to the public, generally (Solomon, 2010). Solomon (2010, p.15) describes stakeholder theory as having the following premise, “companies are so large, and their impact on society so pervasive, that they should discharge an accountability to many more sectors of society than solely their shareholders”. In terms of management behaviour, stakeholder theory takes managers to be accountable to all stakeholders, diverging significantly from both agency and stewardship theory (Chen & Roberts, 2010).

In stakeholder theory, a firm must guarantee, or at least support, the interests of many stakeholders, not only shareholders (Solomon, 2010) all with varying expectations. For example, workers expect better income and job security whilst shareholders expect better returns, creditors expect the firm to have a solid financial position to protect their investments and policy-makers seek compliance with diverse policy agendas including corporate governance rules.

Principally, stakeholder theory assumes that firms operate in the interests of society generally and not only in the interests of their owners (Chen & Roberts, 2010). It extends this responsibility to managers who should be accountable to all stakeholders, employees, creditors, customers, suppliers and the local community (Clarke, 1998). Given this, stakeholder theory has strong links to ideas of corporate social responsibility and morality in business (Westphal & Zajac, 2013).

Steenberg (1997), identifies that stakeholder theory has been questioned from several perspectives. It contradicts the main aim of wealth maximisation for shareholders and interferes with manager-shareholder accountability. It has even been argued that stakeholder theory runs counter to the core principles of corporate governance (Albassam, 2014). However, Clarke (1998) and Chen & Roberts (2010) demonstrate that stakeholder theory remains one of the major corporate governance theories, currently.

Stakeholder Theory and the Jordanian Corporate Environment

The 2006 JCGC contains guidelines on protecting the interests of stakeholders, as well as corporate social responsibility, in line with its Western roots, so there exist expectations that Jordanian companies serve the interests of a much wider stakeholder group than shareholders. Similarly, the Islamic view of corporate governance holds that corporate governance be value-based and promote justice for all participants (Al-Turki, 2006). Zakat1 is an example of Islamic values providing charity in society improving the relationship between companies and society (Nadzri et al., 2012).

The Jordanian context does hold challenges for stakeholder theory. Again, high concentration of ownership suggests that an increased power and predisposition of large shareholder families or individuals to consider their own interests before others, including to the detriment of other stakeholders and wider society. Furthermore, corporate governance as a concept and an activity is relatively new to Jordan (Shanikat & Abbadi, 2011) and an appreciation of effective corporate governance systems is relatively low for shareholders and managers. This all serves to make stakeholder theory less relevant to the current and actual practices of Jordanian companies.

Resource Dependence Theory

The premise of resource dependence theory is that external resources, such as raw materials, capital investment and labour skills, can be determining factors in the behaviour and performance of a firm. Pfeffer & Salancik (1978) state that company success depends on managing and controlling essential environmental resources. According to this theory, by appropriating key resources and enforcing a proactive managerial system to resource management, companies can increase their performance and wealth (Pfeffer, 1981). What is more, with such an approach the firm minimises outside risks. Chen & Roberts (2010, p.653) argue that “Organizations are not self-contained or self-sufficient, they rely on their environment for existence, and the core of the [resource dependence] theory focuses on how organizations gain access to vital resources for survival and growth.”

Resource dependence theory views the board and its directors as a key internal resource in appropriating external resources, for example, establishing business connections and deals, and offering advice to managers (Nicholson & Kiel, 2007; Chen, 2011). The board is a crucial connection between the firm and financial and non-financial resources and accesses external resources, liaising with other firms and key authorities augmenting firm performance and wealth maximisation (Corbetta & Salvato, 2004; Pfeffer, 1972; Pearce & Zahra, 1992; Sing et al., 1986).

The background, qualifications and experience of directors provide necessary resources for the company, for example, the executive director of a financial institution can ease access to credit insurance lines, a lawyer may help to reduce the cost of security through the legal advice they offer (Daily et al., 2003). Kaplan & Minton (1994) studied external directors on the boards of Japanese companies and found that businesses frequently recruit financial directors when faced with a falling share price or other poor firm performance. Resource dependency theory, posits that a board of directors can represent many stakeholders, for example, employees, customers, creditors, suppliers and policy-makers (Nicholson & Kiel, 2007). Thus, the board of directors is a open channel for the firm to the environment where it operates and improved access to external resources means competitive advantage for the firm (Chen & Roberts, 2010).

Resources dependency theory proposes that family members with higher skills and resources will help to improve firm performance. Dalton et al. (1998) argue that family members who are directors have greater incentive to offer resources like counsel and advice, promoting connections with other organisations, and improving the reputation of the firm. Astrachan et al. (2002) see family members as adding important knowledge to a company. Resources appropriated via family members “enable the firm to conceive of and implement strategies that improve its efficiency and effectiveness” (Barney, 1991, p.101).

Resource Dependence Theory and the Jordanian Corporate Environment

The board of directors and ownership structure of Jordanian companies play an important role in enhancing corporate performance, which is consistent with the perspective of resource dependency theory. Jordanian society is characterised by strong social relationships, and personal relationships help to negotiate business contracts and improve the connection between the firm and its environment. Adeyemi-Bello & Kincaid (2012) state that the personal networks which directors bring to a company support it in accessing resources. Resource dependence theory also offers an explanation for the structure of firms in Jordan, as family firm structure brings in internal and external business networks created by the family members to benefit the company as reflected in Jordanian firms which are usually controlled by large block-holders, members of one family (Marashdeh, 2014).

Institutional Theory

Institutional theory is a key theoretical perspective in the social sciences, particularly in accounting (Scott, 1995). It concentrates on institutional elements that transcend organizational boundaries and minimises the importance of intrinsic motivation (Hoffman, 1999). Institutional theory provides a profound understanding of economic phenomena within the human world, such as cultural, religious, political and technological aspects (Alghamdi, 2012). Institutional theory predicts that a company replicates the practices of another company because they inhabit the same institutional and social systems. The institutional environment is codified as a system of social, political, legal, and economic structures which form the basis of the production of products and services (Yi et al., 2012).

Institutional theory views corporate governance as a change in institutional processes over time. Governance mechanisms “fulfil ritualistic roles that help legitimize the interactions among the various actors within the corporate governance mosaic” (Zainal et al., 2013, p.412). Saudagaran & Diga (1997) state that, rather than efficiency or profit, firms are seeking legitimacy and social acceptance when they implement corporate governance practices, a process which Carpenter & Feroz (2001) call “organisational imprinting”. The process of institutionalisation is a “cultural and political one that concerns legitimacy and power much more than efficiency alone” (Carruthers, 1995, p.315). Both private and public institutions will produce governance regulations to advance legitimacy in society, not to improve efficiency (Khadaroo & Shaikh, 2007).

Institutional Theory and the Jordanian Corporate Environment

Institutional theory offers much for understanding the Jordanian business environment. In 2009, the JSC developed corporate governance codes for Jordanian listed firms. All firms listed on the Amman Stock Exchange are asked to meet these codes improve organizational effectiveness. Yet, these guidelines may not improve firms’ effectiveness, especially when the guidelines fail to acknowledge important economic and cultural factors. Policy makers in Jordan based the JCGC on OECD corporate governance systems, as examples of best practice internationally. There was little consideration of culture, Islamic religion and the preponderance of family firms in Jordan and ignoring these brings into question the appropriateness of these regulations for Jordan. Compliance with the JCGC, offers companies, and in return the JCGC, legitimacy, but without evidence of improved firm performance.

Conclusion

A theoretical basis for understanding corporate governance is essential, but it is problematic to rely on one theory alone (Sharma, 2013). Corporate governance involves many overlapping fields, such as economics, management, finance, politics and ethics (Bebchuk & Weisbach, 2010; Solomon, 2010), and therefore a matrix of theory is useful to develop a more holistic understanding. It has also been demonstrated that any theoretical framework/s must consider real world context, in this case the Jordanian business environment. The specific cultural, religious and social structures defining ownership all impact on corporate governance practices in Jordan and their effectiveness.

Agency theory describes the conflict of interest between principals and agents, and between majority and minority shareholders which is important for understanding corporate governance mechanisms (Robert, 2005). Agency theory proposes corporate governance as a mechanism to reduce managerial opportunism, thus minimising agency costs (Haniffa & Hudaib, 2006). For instance, lessening the number of executive board members to improve the board’s independence to increase the accountability of the board to its shareholders are all supported by agency theory (Bebchuk & Weisbach, 2010; Solomon, 2010). Similarly, CEO duality is seen to be a harmful influence on decision making processes, power relationships and monitoring of management when viewed from an agency theory perspective (Fama & Jensen, 1983; Jensen, 1993). Agency theory can help to get to the heart of the corporate governance issue, highlighting the quality and effectiveness of governance mechanisms.

Agency theory is one of the main theoretical perspectives to investigate corporate governance mechanisms and firm performance (Jensen & Meckling, 1976; Kiel & Nicholson, 2003; Adams & Ferreira, 2009; Mallin, 2010). The board of directors can decrease agency issues through monitoring and disciplinary action acting in their role on behalf of shareholders (Fama, 1980). Yoshikawa & Phan (2003) use agency theory to argue for smaller board size as the most useful and efficient model for organising governance and improving performance. Kiel & Nicholson (2003) insist that performance is improved by the separation of the power of the CEO and chairperson. Independent directors are also strongly viewed as improving corporate governance and firm performance, as it ensures better control over management. (Fama, 1980; Fama & Jensen, 1983; Jensen & Meckling, 1976). Agency theory assists understanding of the impact of the characteristics of board members Adams and Ferreira (2009) demonstrate that female board members improve board monitoring of management. Overall, agency theory provides an excellent foundation for building corporate governance structures and mechanisms (Mallin, 2010).

For the concentrated ownership structure in Jordan and other Arab countries agency theory describes how the interests of key shareholders can be united to reduce agency costs and maximise corporate performance (Chen & Jaggi, 2001). Meanwhile, the board of directors is control management performance on behalf of majority shareholders as well as the weaker minority shareholders.

This article has described other theories relevant to the context of Jordan, such as stewardship, resource dependency and institutional theories. Family owners, common in Jordan, often nominate friends and relatives to the board. Internal and external business relationships can include many close personal and social relationships for board directors in Jordan. This context makes stewardship theory important in understanding directors closeness to their firm and their often intimate knowledge of it as well as their special status in representing the firm externally. Here also, the Jordanian corporate context is aligned to resource dependency theory on the key role of the board in connecting the firm to the resources essential to maximise firm performance and wealth (Adeyemi-Bello & Kincaid, 2012; Hillman & Dalziel, 2003). Finally, institutional theory explains policy development in Jordan related to corporate governance and the development of the 2009 JCGC.

The use of more than a single theory can thus be supported for several reasons. First, all theories are limited in some way to understand the relationship between corporate governance and company performance, which is shown when they are combined and reinforce one another in their explanation. Second, corporate governance is a multi-faceted concept, being informed by a range of disciplines, such as economics, management, and ethics (Solomon, 2010). This reduces any expectation that a single theory can offer a deep explanation of corporate governance. Finally, recent studies have begun a call for theoretical pluralism, highlighting the need to look beyond any single theory and to use a multi-theoretical approach of both complementary and competing theories to research on corporate governance and finance, e.g., (Zattoni et al., 2013).

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the Middle East University, Amman, Jordan for the financial support granted to cover the publication fee of this research article.

1Zakat is an Islamic social tax: Every Muslims must pay Two and five tenths of their wealth each year for charity, such as donations to the needy and poor (Kamla et al., 2006).

References

- Adams, R.B., & Ferreira, D. (2009). Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 94(2), 291-309.

- Adeyemi-Bello, T., & Kincaid, K. (2012). The impact of religion and social structure on leading and organizing in Saudi Arabia. In A. Avery (Ed.), 2012 Southeast Decision Sciences Institute (pp. 347-366). Columbia, South Caroline.

- Adiguzel, H. (2013). Corporate governance, family ownership and earnings management: emerging market evidence. Accounting and Finance Research, 2(4), 17.

- Al Mamun, A., Yasser, Q., & Rahman, M. (2013). A discussion of the suitability of only one vs more than one theory for depicting corporate governance. Modern Economy, 4(1), 37-48.

- Al-Amarneh, A. (2014). Corporate governance, ownership structure and bank performance in Jordan. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 6(6), 192-202.

- Albassam, W. (2014). Corporate governance, voluntary disclosure and financial performance: An empirical analysis of Saudi listed firms using a mixed-methods research design. (Ph.D.), University of Glasgow.

- Al-Ghamdi, M., & Rhodes, M. (2015). Family ownership, corporate governance and performance: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 7(2), 78.

- Alghamdi, S. (2012). Investigation into earnings management practices and the role of corporate governance and external audit in emerging markets: Empirical evidence from Saudi listed companies. (Ph.D.), Durham University.

- Al-Haddad, W., Alzurqan, S.T., & Al-Sufy, F.J. (2011). The effect of corporate governance on the performance of Jordanian industrial companies: An empirical study on Amman Stock Exchange. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 1(4), 55-69.

- Ali, A., Chen, T.Y., & Radhakrishnan, S. (2007). Corporate disclosures by family firms. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 44, 238-286.

- Al-jazi, O.H. (2007). Corporate Governance in Jordan, available online at http://www.aljazylaw.com/arabic/pdf/hawkamat_alsherkat2.pdf.

- Al-Muhtaseb, B. (2009). The Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on the Economic Growth of Jordan (1990-2006). Dirasat: Administrative Sciences, 36(2).

- Al-Turki, K. (2006). Corporate governance in Saudi Arabia: Overview and empirical investigation. (Ph.D.), Victoria University.

- Al-Wasmi, M. (2011). Corporate Governance Practice In the GCC: Kuwait as a Case Study. (Ph.D.), Brunel.

- Anderson, R.C., & Reeb, D. (2004). Board Composition: Balancing Family Influence in S&P 500 Firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49, 209-237.

- Anderson, R., & Reeb, D. (2003). Founding-family ownership and firm performance: Evidence from the S & P 500. Journal of Finance, 58(3), 1301-1328.

- Arnold, B., & De Lange, P. (2004). Enron: An Examination of Agency Problems. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 15(6), 751-765.

- Astrachan, J.H., Klein, S.B., & Smyrnios, K.X. (2002). The F-PEC scale of family influence: A proposal for solving the family business definition problem. Family Business Review, 15(1), 45-58.

- Barclay, M., & Holderness, C. (1989). Private benefits from control of public corporation. Journal of Financial Economics, 25, 371-395.

- Barney, J.B. (1991) Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage, Journal of Management, 17, 99-120.

- Baydoun, N., Maguire, W., Ryan, N., & Willett, R. (2013). Corporate governance in five Arabian Gulf countries’, Managerial Auditing Journal, 28(1), 7-22.

- Bebchuk, L., & Weisbach, M. (2010). The state of corporate governance research. The Review of Financial Studies, 23(3), 939-961.

- Berle, A., & Means, G. (1932). The modern corporation and private property. London: Transaction Publishers.

- Blair, M. (1995). Ownership and control: Rethinking corporate governance for the twenty-first century. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution.

- Boubakri, N., & Ghouma, H. (2010). Control/ownership structure, creditor rights protection, and the cost of debt financing: International evidence. Journal of Banking & Finance, 34(10), 2481-2499.

- Burkart, M., Gromb, D., & Panunzi, F. (1997). Large shareholders, monitoring, and the value of the firm. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(3), 693-728.

- Cadbury, A. (2000). Family firms and their governance: Creating tomorrow’s company from today’s. London: Egon Zehnder International.

- Carpenter, V., & Feroz, E. (2001). Institutional theory and accounting rule choice: An analysis of four US state governments' decisions to adopt generally accepted accounting principles. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 26(7-8), 565-596.

- Carroll A., Buchholtz A. (2003). Business and Society, Ethics and Stakeholders Management, 5th Edition. Thomson, Mason (Ohio)

- Carruthers, B. (1995). Accounting, ambiguity and the new institutionalism. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 20(4), 315-328.

- Chen, C.J., & Jaggi, B. (2001). Association between Independent Non-Executive Directors, Family Control and Financial Disclosures in Hong Kong. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 19(4), 285-310.

- Chen, J., & Roberts, R. (2010). Toward a more coherent understanding of the organization–society relationship: A theoretical consideration for social and environmental accounting research. Journal of Business Ethics, 97(4), 651-665.

- Chen, S., Chen, X., Cheng, Q., & Shevlin, T. (2010). Are family firms more tax aggressive than non-family firms?. Journal of Financial Economics, 95(1), 41-61.

- Chrisman, J.J., Chua, J.H., & Sharma, P. (2005). Trends and directions in the development of a strategic management theory of the family firm. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 29(5), 555-576.

- Clarke, T. (1998). The stakeholder corporation: A business philosophy for the information age. Long Range Planning, 31(2), 182-194.

- Clarke, T. (2004). Theories of corporate governance: The philosophical foundations of corporate governance. London: Routledge.

- Conyon, M., & He, L. (2011). Executive compensation and corporate governance in China. Journal of Corporate Finance, 17(4), 1158-1175.

- Corbetta, G., & Salvato, C.A. (2004). The board of directors in family firms: One size fits all? Family Business Review, 17(2), 119-134.

- Daily, C.M., Dalton, D.R., & Cannella, A.A. (2003). Corporate governance: Decades of dialogue and data. Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 371-382.

- Dalton, D., Daily, C., Ellstrand, A., & Johnson, J. (1998). Meta-analytic reviews board composition, leadership structure and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 19(3), 269-290.

- Davis, J., Schoorman, F., & Donaldson, L. (1997). Towards a stewardship theory of management. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 20-47.

- Demsetz, H., & Lehn, K. (1985). The structure of corporate ownership: Causes and consequences. Journal of Political Economy, 93(6), 1155-1177.

- Demsetz, H. (1983). The structure of ownership and the theory of the firm. Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 375-390.

- Denis, D., & McConnell, J. (2003). International corporate governance. Journal of Financial & Quantitative Analysis, 38(1), 1-36.

- Denis, D. (2001). Twenty-five years of corporate governance research … and counting. Review of Financial Economics, 10(3), 191-212.

- Dharwadkar, R., George, G., & Brandes, P. (2000). Privatization in Emerging Economies: An Agency Theory Perspective. Academy of Management Review, 25(3), 650-669.

- Donaldson, L., & Davis, J. (1991). Stewardship theory or agency theory: CEO governance and shareholder returns. Australian Journal of Management, 16(1), 49-69.

- Donaldson, L., & Davis, J. (1994). Boards and company performance - research challenges the conventional wisdom. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 2(3), 151-160.

- Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. (1995). The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 65-91.

- Eisenhardt, K. (1989). Agency theory: An assessment and review. The Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 57-74.

- Ekanayake, S. (2004). Agency theory, national culture and management control systems. The Journal of American Academy of Business Cambridge, 4(1/2), 49?54.

- Faccio, M., Lang, L.H., & Young, L. (2001). Dividends and expropriation. American Economic Review, 91(1), 54-78.

- Fama, E.F. (1980). Agency Problems and the Theory of the Firm. The Journal of Political Economy, 288-307.

- Fama, E., & Jensen, M. (1983). Agency problems and residual claims. Journal of Law and Economics, 26, 327-349.

- Freeman, R. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Freeman, R. (1999). Divergent stakeholder theory. Academy of Management Review, 24(2), 233-236.

- Grant, G.H. (2003). The evolution of corporate governance and its impact on modern corporate America. Management Decision, 41(9), 923-934.

- Haniffa, R., & Hudaib, M. (2006). Corporate governance structure and performance of Malaysian listed companies. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 33(7-8), 1034-1062.

- Hart, O. (1995). Corporate Governance: Some Theory and Implications. The Economic Journal, 105(430), 678-689.

- Hendriksen, E. (1970). Accounting Theory. Illinois: Richard D. Irwin.

- Hillman, A., & Dalziel, T. (2003). Boards of directors and firm performance: Integrating agency and resource dependence perspectives. Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 383-385.

- Hoffman, A. (1999). Institutional evolution change: Environmentalism and the U.S. chemical industry. Academy of Management Journal, 42(4), 351-371.

- Holderness, C.G. (2003). A Survey of Block holders and Corporate Control. Economic Policy Review, 9(1), 51-64.

- Homayoun, S., & Homayoun, S. (2015). Internet-Based Compulsory Information Disclosure by Listed Companies in Tehran Stock Exchange. International Business Management, 9(5), 791-797.

- Ibrahim, A.H., & Hanefah, M.M. (2016). Board diversity and corporate social responsibility in Jordan. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 14(2), 279-298.

- IFC family business governance handbook. (2011). Washington, D.C.: International Finance Corporation.

- Jensen, M., & Meckling, W. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305-360.

- Jensen, M. (1993). The modern industrial revolution, exit and the failure of internal control systems, Journal of Finance, 48, 831-880.

- Jordan Corporate Governance Code. Available online at: www.ccd.gov.jo/uploads/CG%20Code%English.pdf.

- Kaplan, S.N., & Minton, B.A. (1994). Appointments of Outsiders to Japanese Boards: Determinants and Implications for Managers. Journal of Financial Economics, 36(2), 225-258.

- Khadaroo, I., & Shaikh, J. (2007). Corporate governance reforms in Malaysia: Insights from institutional theory. World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 3(1), 37-49.

- Kiel, G., & Nicholson, G. (2003). Board Composition and Corporate Performance: How the Australian Experience Informs Contrasting Theories of Corporate Governance. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 11(3), 189-205.

- La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (1999). Corporate ownership around the world. Journal of Finance, 54(2), 471-517.

- La Porta, R., Lopez-De-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R. W. (1998). Law and Finance. Journal of Political Economy, 106, 1113-1155.

- La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (2000). Investor's protection and corporate governance. Journal of Financial Economic, 58(1), 3-17.

- Lemmon, M., & Lins, K. (2003). Ownership structure, corporate governance, and firm value: Evidence from the East Asian financial crisis. Journal of Finance, 58(4), 1445-1468.

- Ling, Y., Lubatkin, M., & Schulze, W. (2001). Altruism, utility functions and agency problems at family firms. In Strategies and organizations in transition (pp. 171-188). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Mallin, C. (2007). Corporate Governance (second edition ed.): Oxford University Press.

- Mallin, C.A. (2010), Corporate governance, 3th edn, Oxford University Press, New York.

- Manawaduge, A. (2012). Corporate governance practices and their impacts on corporate performance in an emerging market: The case of Sri Lanka. (Ph.D.), University of Wollongong.

- Marashdeh, Z. (2014). The Effect of Corporate Governance on Firm Performance in Jordan. (Ph.D.), The University of Central Lancashire, UK.

- Mark, G. (1987). The personification of the business corporation in American law. University of Chicago Law Review, 54, 1441-1483.

- Martínez-Ferrero, J., Rodríguez-Ariza, L., Dan Bermejo-Sánchez, M. (2016). Is family ownership of a firm associated with the control of managerial discretion and corporate decisions? Journal of Family Business Management, 6(1), 23-45.

- Morck, R., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R.W. (1988). Management Ownership and Market Valuation: An Empirical Analysis. Journal of Financial Economics, 20, 293-315.

- Nadzri, F., Abdrahman, R., & Omar, N. (2012). Zakat and poverty alleviation: Roles of zakat institutions in Malaysia. International Journal of Arts and Commerce, 1(7), 61-72.

- Nicholson, G.J., & Kiel, G.C. (2007). Can Directors Impact Performance? A Case?Based Test of Three Theories of Corporate Governance. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 15(4), 585-608.

- Ongore, V.O., & K’Obonyo, P.O. (2011). Effects of selected corporate governance characteristics on firm performance: empirical evidence from Kenya. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 1(3), 99-122.

- Padilla, A. (2002). Can agency theory justify the regulation of insider trading?’, Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, 5(1), 3-38.

- Pearce, J.A., & Zahra, S.A. (1992). Board Composition from a Strategic Contingency Perspective. Journal of Management Studies, 29(4), 411-438.

- Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. (1978). The external control of organizations: A resource dependence approach. New York: Harper & Row.

- Pfeffer, J. (1972). Size and composition of corporate boards of directors: The organization and its environment. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17(2), 218- 228.

- Pfeffer, J. (1981). Power in organizations. Pitman Publishing, Marshfield. MA.

- Pindado, J., & Requejo, I. (2015). Family Business Performance from a Governance Perspective: A Review of Empirical Research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 17(3), 279-311.

- Price, R., Román, F.J., & Rountree, B. (2011). The impact of governance reform on performance and transparency. Journal of Financial Economics. 99(1), 76-96.

- Roberts, J. (2005). Agency theory, ethics and corporate governance. Advances in Public Interest Accounting, 11, 249-269.

- ROSC. (2004). Report on the Observance of Standards and Cods, Corporate Governance Country Assessment, Jordan, available online at: www.worldbank.org/ifa/jor rosc cg.pdf.

- Ross, S.A. (1973). The economic theory of agency: the principal’s problem, American Economic Review, 63(2), 134-139.

- Saudagaran, S., & Diga, J. (1997). Accounting regulation in ASEAN: A choice between the global and regional paradigms of harmonization. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting, 8(1), 1-32.

- Schulze, W.S., Lubatkin, M.H., & Dino, R.N. (2003). Exploring the Agency Consequences of Ownership Dispersion among the Directors of Private Family Firms. Academy of Management Journal, 46(2), 179-194.

- Scott, W. (1995). Institutions and organizations. London/New Delhi: Sage Publications.

- Shanikat, M., & Abbadi, S.S. (2011). Assessment of corporate governance in Jordan: An empirical study. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 5(3), 93-106.

- Sharma, N. (2013). Theoretical framework for corporate disclosure research. Asian Journal of Finance & Accounting, 5(1), 183-196.

- Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1997). A survey of corporate governance. Journal of Finance, 52(2), 737-783.

- Siebels, J., & Knyphausen?Aufseb, D. (2012). A review of theory in family business research: The implications for corporate governance. International Journal of Management Reviews, 14(3), 280-304.

- Sing, J.V., House, R.J., & Tucker, D.J. (1986). Organizational change and organizational mortality. Administrative Science Quarterly, 31(4), 587-611.

- Sternberg, E. (1997). The Defects of Stakeholder Theory. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 5(1), 3-10.

- Stulz, R. (1988). Managerial Control of Voting Rights: Financing Policies and the Market for Corporate Control. Journal of Financial Economics, 20, 25-54.

- Tarraf, H. (2010). Literature review on corporate governance and the recent financial crisis.

- Van den Berghe, L.A.A., & Carchon, S. (2002). Corporate governance practices in Flemish family businesses. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 10(3), 225-245.

- Villalonga, B., & Amit, R. (2006). How do Family Ownership, Control and Management Affect Firm Value? Journal of Financial Economics, 80(2), 385-417.

- Wang, D. (2006). Founding family ownership and earnings quality. Journal of Accounting Research, 44(3), 619-656.

- Watts, R., & Zimmerman, J. (1986). Positive Accounting Theory. Prentice-Hall Inc., Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey.

- Westphal, J., & Zajac, E. (2013). A behavioral theory of corporate governance: Explicating the mechanisms of socially situated and socially constituted agency. The Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 605-659.

- Wiwattanakantang, Y. (2001). Controlling Shareholders and Corporate Value: Evidence from Thailand. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 9(4), 323-362.

- Yi, Y., Liu, Y., He, H., & Li, Y. (2012). Environment, governance, controls, and radical innovation during institutional transitions. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 29, 689-708.

- Yoshikawa, T., & Phan, P.H. (2003). The performance implications of ownership-driven governance reform. European Management Journal, 21(6), 698-706.

- Young, C.S., Tsai, L.C., & Hsieh, P.G. (2008). Voluntary appointment of independent directors in Taiwan: Motives and consequences. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 35(9/10), 1103-1137.

- Zainal, A., Rahmadana, M., & Zain, K. (2013). Power and likelihood of financial statement fraud: Evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Advanced Management Science, 1(4), 410-415.

- Zattoni, A., Douglas, T., & Judge, W. (2013). Developing corporate governance theory through qualitative research. Corporate Governance, 21(2), 119-122.

- Ziolkowski, R. (2005). A reexamination of corporate governance concepts, models and theories and future direction. (Ph. D.), University of Canberra.