Research Article: 2024 Vol: 28 Issue: 5S

Age Cues in Advertising: Literature Review and Future Research Agenda

Fathima Siyana P, Indian Institute of Management-Kozhikode

Citation Information: Siyana, P. (2024). Age cues in advertising: literature review and future research agenda. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 28(S5), 1-23.

Abstract

The effectiveness of advertisements depends on reaching the targeted consumers and communicating the content meaningfully and positively to them. Although the impact of age on consumers’ information processing and responses to advertisements is well documented in the existing literature, the research on age or age-related information or cues and consumers’ response to them is spread across multiple domains and lacks a comprehensive understanding. Thus the main objective of this review is to critically analyse the existing studies on the topic and thereby find major concepts and themes in them. Moreover, the study also summarizes key findings, patterns, or relationships in the existing studies in an integrated format. Finally, the review identifies and outlines the knowledge gaps that arise from this analysis. The study puts forth a few prospective research directions that could provide meaningful insights from a theoretical and practical perspective.

Keywords

Age Cues, Age in Advertisement, Information processing, Consumer response, Congruence, Older Consumers.

Introduction

Advertising creates narratives that match brands/products with consumers' wants and needs through strategic messaging, emotional resonance, and expert information delivery (Bauer, 2023). It creates a persuasive ecology that leads customers to make informed decisions and adopt desired behaviors by utilizing psychological triggers, utilizing relatable storylines, and addressing pain spots (Vakratsas & Ambler, 1999; Bauer, 2023). However, the modern advertising landscape bombards consumers with a wide range of promotional messages across various platforms and media outlets, raising concerns among advertising professionals about the genuine impact of their work (Zhang & Buda, 1999). Crafting customized appeals for each demographic becomes essential for increasing advertising effectiveness when consumers must traverse a veritable flood of advertising (Jang et al, 2014). As a result, marketers focused more of their efforts on precisely segmenting customers based on their unique needs and preferences (Grove & Fisk, 1997). Age, race, and gender are a few socio-demographic characteristics influencing this tailored approach (Hollis, 2005). Age emerges as a critical factor in this intricate interplay, a discovery that is corroborated by research that shows how crucial age is in determining the effectiveness of persuasive advertising (Drolet et al, 2007). Advertisers skillfully adapt their communication techniques to harmonies with particular age groupings since they are aware of how powerful age-related appeals can be in connecting with consumers.

A wide range of topics are covered in the past literature on the impact of age or age-related information in advertising research. This collection of research provides a broad examination of age cues in advertising; however, a thorough synthesis of these studies is necessary to gain a deeper understanding and open the door for more nuanced viewpoints in this dynamic field.

Although much research has looked at age-related information, most of these investigations have tended to be non-comprehensive and lack the depth needed to understand the many complexities underlying this phenomenon fully. While previous research indicates that consumers' age affects how they respond to commercials (Fung & Carstensen, 2003; Phillips & Stanton, 2006; Drolet et al., 2007), there aren't many studies that have looked at how specific factors like attention span and engagement levels interact with age in various media situations. The use of models and celebrities to transmit age-relevant information in advertising also shows a clear pattern (Chang, 2008; Pezzuti et al., 2015; Roy et al., 2015), although research into the more significant ramifications of these tactics is surprisingly understudied. The lack of thorough attempts to combine information from many disciplines highlights the need for a synthesized perspective to uncover latent relationships and patterns. The literature that is now available, predominantly of older studies (Weijters & Geuens, 2006; Wolf et al., 2014), has produced less conclusive answers that fall short of exploring the depths of this complex interplay. As a result, a clear gap develops, calling for a more thorough investigation and a more coherent and synthesized framework that may collectively inform academic scholarship and practical advertising-related tactics.

Thus, the current investigation is a systematic literature review, where there are three main objectives. Its first objective is to critically assess all previous research on age cues in advertising. This study aims to provide a comprehensive examination and assessment of the present state of knowledge by compiling and critically assessing a wide range of scholarly studies in this domain, covering the aspects and the relationship between age-related cues and advertising efficacy. Secondly, this study tries to identify the key topics that have drawn researchers' attention by synthesizing the knowledge gained from these many investigations. It attempts to identify patterns, relationships, and gaps that might not be obvious when looking at individual research in isolation through this process of synthesis. Finally, this review aims to explore plausible gaps in the literature. It aims to open the door for more research by pointing out specific places where it is scarce or dispersed. This entails outlining possible research avenues that can fill in these knowledge gaps, thus promoting the development of a more complex and in-depth comprehension of age cues in advertising. In conclusion, this review aims to contribute by condensing, synthesizing, and expanding the existing body of information regarding age cues in advertising, ultimately guiding both scholarly investigation and practical directions in this dynamic area.

This comprehensive analysis of the literature makes a substantial contribution to the theoretical debate and real-world applications in advertising. Theoretically, synthesizing and analysing a broad range of studies on age cues in advertising offer a thorough framework that enhances our comprehension of the complex interaction between age-related information and consumer behaviour. This assessment uncovers hidden linkages, finds overarching themes, and pinpoints gaps in the present understanding by methodically analyzing the body of existing knowledge. The development and growth of theoretical constructs connected to age cues in advertising are made possible by this, which in turn creates the groundwork for future scholars to explore more deeply into certain fields. Additionally, by providing a comprehensive viewpoint, this study gives coherence to the previously disjointed material, aiding in the development of a more comprehensive and integrated understanding of the issue. The contributions made by this review are equally significant from a practical perspective. Advertising professionals face the difficulty of developing campaigns that connect with a variety of audiences as the advertising landscape grows more dynamic and competitive. The conclusions drawn from this systematic study work as a tactical manual for practitioners, providing evidence-based advice on how age-related cues might be strategically used to improve the potency of advertising messages. This analysis provides practitioners with useful insights that enable the customization and optimization of their campaigns by detecting patterns of consumer responses, media context interactions, and the impact of age-related cues beyond simple celebrity endorsements. Bridging the gap between academic scholarship and practical application allows practitioners to make well-informed judgments that not only take into account the most recent research but also result in noticeable advancements in advertising tactics.

Thus, in the subsequent section, we present the methodology followed to collect and analyses the past body of works in the domain. Further, we presented a detailed overview that discover underlying patterns and linkages that emerge from this topic's varied studies by meticulously analyzing a broad selection of scholarly literature on age cues in advertising. This synthesis attempts to uncover underlying patterns that might not be immediately apparent when scrutinizing individual investigations by contrasting results from studies that explore the influence of consumers' age on their responses to advertisements, the evaluation of age-related cues in marketing communications, and the impact of models' age on consumer perceptions. In the next section, we aim to draw attention to knowledge gaps. This part establishes the framework for a more coherent and structured understanding of age cues in advertising by providing a thorough synthesis that fills in the gaps and ties everything together. Thus, the discussion of the identification of potential directions for future study is made possible, leading to a more nuanced understanding of the interaction between age cues and the effectiveness of advertising.

Review Methodology

A systematic literature review (SLR) is a structured process of identifying, analysing, and interpreting existing research on a specific topic through a transparent, systematic, unbiased, and replicable analysis (Vrontis & Christofi, 2021). The process of systematic literature review analyses the previous research outcomes and confirms the findings, identifies the conflicts, compares similar findings, etc., and paves the way for future research contributions (Gossen et al., 2019). Thus SLR is the most sophisticated and popular method used to synthesize literature in a specific domain (Linnenluecke et al., 2020).

The next section explains the step-wise procedure for searching, filtering, categorizing, and analysing publications on the topic of age or age-related information or messages in advertisements. A successful review is based on clear research questions being developed at the start of the review process (Nguyen et al., 2018), hence, this systematic literature review was guided by the following questions:

1. What is the current state of knowledge on age cues in advertising and what are the key findings, trends, and gaps in the existing literature?

2. How key findings and insights from different studies have in the area of age cues in advertising evolved over time, and what implications does this temporal perspective have for understanding this domain better?

3. What are the gaps, inconsistencies, or contradictory findings within the current literature, and how can addressing these gaps lead to informed and targeted future research efforts?

Search Strategy

After outlining the research questions for the review process the suitable keywords were identified and databases were selected to search for the relevant studies. The process is detailed below

Keywords Identification

The keywords for the search process were identified based on the method adapted by Chopra et al. (2023). The first step was to identify the terms synonymous and used interchangeably with ‘age cues in advertisements’. Then the existing literature was reviewed to determine the most commonly used keywords in connection to ‘age cues in advertisements’ in previously published papers. The final keywords identified were approved after review. The boolean ‘OR’ and ‘AND’ operator was used for the keyword search. The final keywords for the article search were “age OR age group OR age difference OR age-related” AND “cues OR messages OR information” AND “advertising OR advertisements OR ads OR commercials OR marketing”.

Previous SLRs in noteworthy journals recommend the use of multiple databases for article search (Paul & Feliciano-Cestero, 2020; Srivastava et al., 2020). To locate appropriate studies for the review, electronic databases such as Business Source Ultimate, Scopus, JSTOR, EMERALD, ProQuest, Sage, Google Scholar, and ScienceDirect were used. The databases covered all relevant journals from the business field and the most commonly used databases in SLRs (Boerman et al., 2017; Cavalinhos et al., 2021; Jebarajakirthy et al., 2021).

The articles related to age cues in advertising were searched from the databases using the identified keywords. The search focused on publications in peer-reviewed academic journals that had full texts. The book chapters, extended abstracts, editorials, conference papers, and book reviews were avoided. The language restriction came next. The review was limited to publications in the English language alone. Articles published in peer-reviewed journals, that were either on the ADBC ranking list or ABS ranking list were included in the review (Srivastava et al., 2020; Chopra et al., 2023). This screening ensures the quality of articles included in the SLR for more impactful findings. The screening based on these indices is also recommended by SLRs published in top-rated journals (Chintalapati & Pandey, 2022; Chopra et al., 2023).

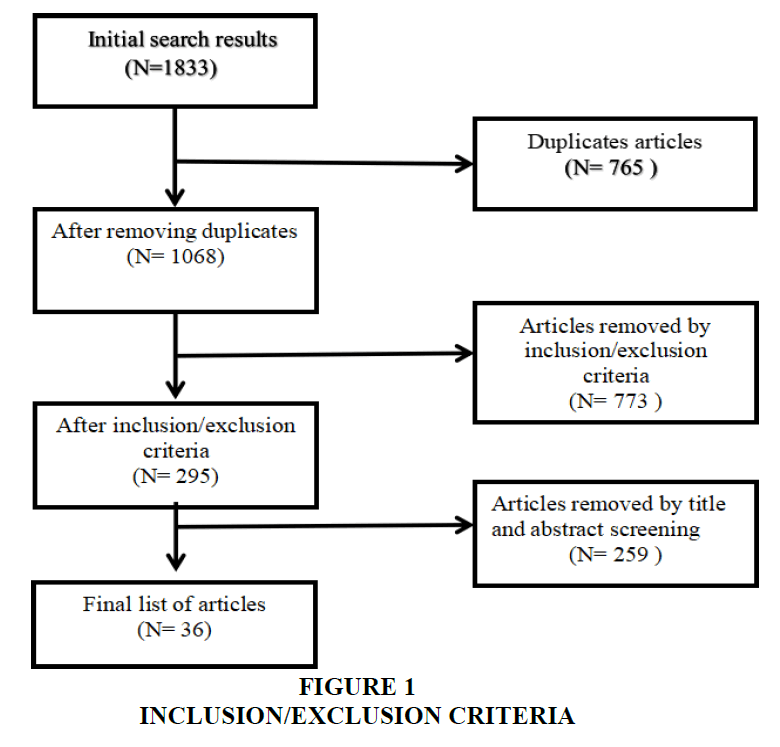

Initial search from these databases produced 1833 hits. Next, the list was screened for duplicate works which were downloaded more than once. After removing this resulting number of articles came about to 1068. The inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied next which brought down the number of studies to 294. The titles and abstracts of all these studies were screened. Only the studies associated with the age or age-related information or messages or cues and its influence on advertisements and thereby on consumer responses were included in the review. The final list included 36 studies. The later process involved content analysis of the final 36 articles. This was considered a suitable number of studies for the review because recently published noteworthy SLRs included a similar number of studies (Akhmedova et al., 2021; Du et al., 2021; Siachou et al., 2021). The characteristics of the paper were tabulated through this process which included publication details, main purpose of the paper, key findings, context of the study, methodology, etc. The overall nature of extant literature, its methodological characteristics, and research boundaries were identified which is described in detail in the next section Figures 1-4.

Descriptive Analysis

Age Cues In Advertisements over the Years

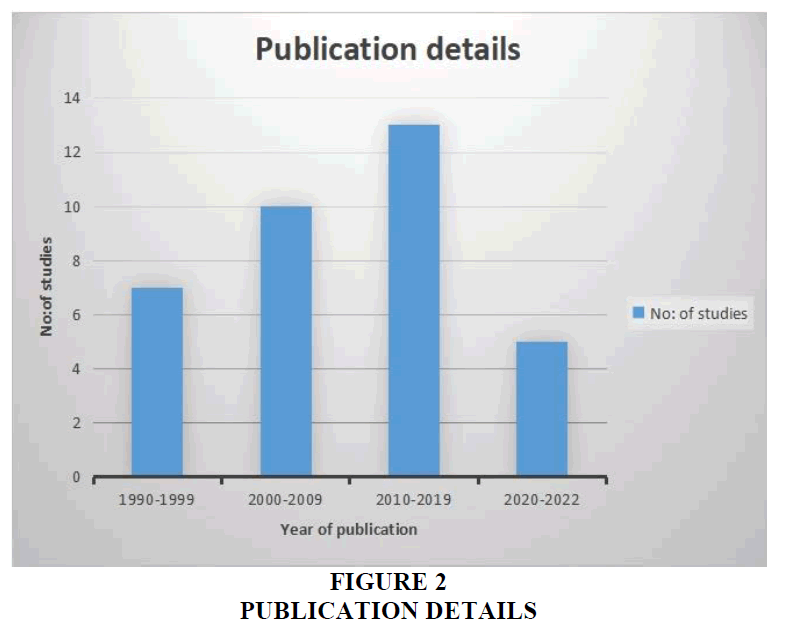

Periodical analysis of research papers on age cues in advertisements reveals the evolution of the topic in advertising research over time (Jebarajakirthy et al., 2021). In this review, we can see that the earliest research study was in the year 1986. Later, between 1990 to 1999, only 8 articles (22.2%) were found on the topic. The number of published studies was consistently increasing, with 10 (27.8%) published studies between the years 2000 and 2009 and 13(36.1%) between the years 2010 and 2019, and 5 from the years 2020 to 2022. From the steady growth in the research articles over time, it can be assumed that the concept of age cues in advertisements has been gaining prominence in recent years. It may be due to the evolution of the concept of age in marketing (Moschis, 2012) or the growing focus on the heterogeneity in behaviours of consumers of similar age (Chevalier & Lichtlé, 2012; Rosenthal et al., 2021).

Publication Outlets

The 36 studies included in the review have been published in 18 different academic journals of international repute. The maximum number of studies (6) was from the Journal of Advertising. The review also included more than one published study from prominent advertising journals like the International Journal of Advertising (3) and the Journal of Advertising Research (3). The rest of the studies were not just limited to journals of advertising, but also from different research domains like psychology, retailing, sociology, marketing communications, etc. This indicates the relevance of this topic for researchers of various fields and with different objectives.

Research Design

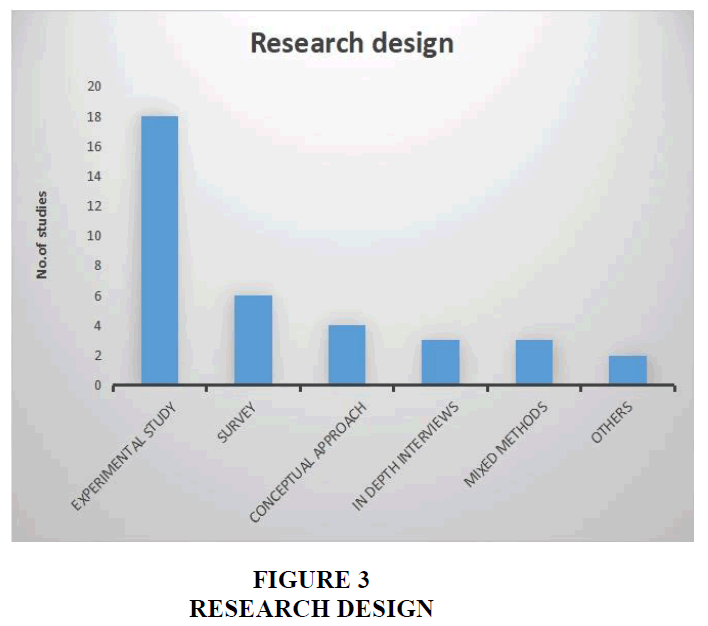

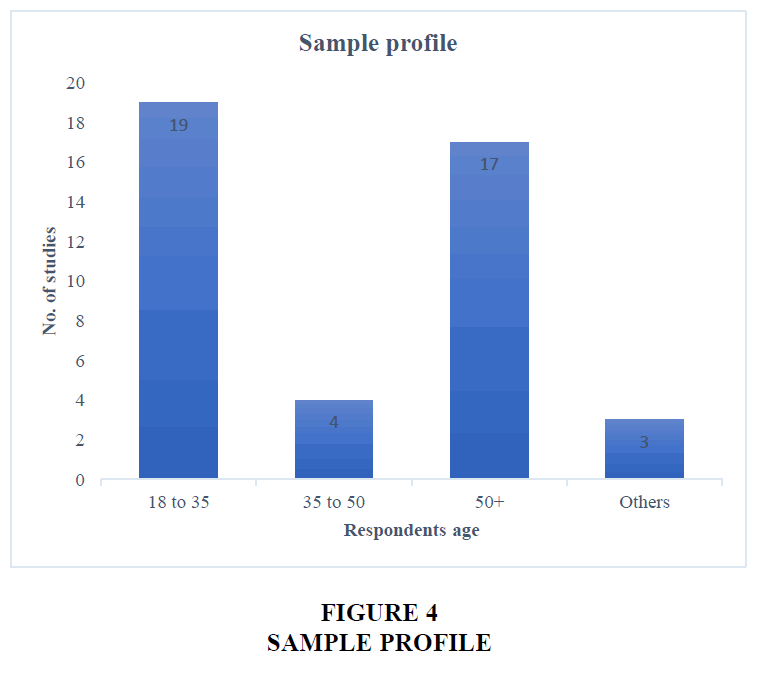

The synthesis of research methods of the studies included in the review reveals that majority (50%) of them are experimental studies since experimental studies are most useful in studying the cause-effect responses to advertisements. In qualitative methods, in depth interviews (3 studies) were prominently used. Another 3 studies used a combination of methods, which included interviews and surveys/experiments. 4 studies in the review adopted a conceptual approach. It was also observed that among the quantitative methods, the survey method was used in 6 of the studies. In terms of the sample considered, most of the studies preferred respondents from two or more different age groups to compare their reactions to age-related cues in advertisements. Among the comparison studies one set of respondents mostly were mature consumers of age above 50. This may be because age-related changes are more evident in consumers of older age groups.

Synthesis and Analysis

In this systematic literature review, to provide critical assessment, synthesis, and analysis, we followed a conceptual analysis and synthesis perspective. Conceptual analysis and synthesis involve distilling the key themes, concepts, theories, and models from the prior studies to develop a comprehensive understanding of the topic. This approach aims to contribute to the theoretical framework of the field and to generate new insights or perspectives (Vrontis et al., 2020; Paul & Feliciano-Cestero, 2020). The following steps were implemented to perform the conceptual synthesis of the prior findings. First, we identified the central themes, concepts, models, and theories which are pertinent to the prior literature. Following this, in the second stage, we extracted the insights related to these concepts from each study. Then in the third stage, mapped out relationships between concepts and identified the patterns and variations. Followed by this, in the fourth stage, we highlighted inconsistencies, gaps, and commonalities across studies. In the last stage, we draw implications and conclusions based on the synthesized understanding. In the following sections, we provided a detailed elucidation of the key concepts identified from the prior literature, its relationship and variations, and the gap extracted, and finally the practical and academic implications of the same Table 1.

| Table 1 Articles Included in the Review | ||

| Author(s) | Major themes | Major Findings |

| John & Cole (1986) | Understanding the similarities in information processing capabilities of young and elderly consumers | • Analysed the effect of task factors on the processing deficit of consumers of different age groups |

| Stephens (1991) | Relevance of cognitive age in advertising | • Advertisements targeted toward consumers’ cognitive age increase their effectiveness |

| Stout &Rust(1993) | Examines the relationship between viewers' emotional response and their evaluation of television commercials | • Demographic characteristics like age and gender influence viewers’ emotional response and their evaluation of ads |

| Tepper (1994) | Analysing consumers' response to age segmentation cues | • Identified mediation effect of self-devaluation and perceived stigma on consumers’ response and analysed consumers resistance to age segmentation cues due to threat to the self-image |

| Oates et al (1996) | Utilizing psychographic variables for market segmentation, especially in the case of older consumers | • Explores the limitations of age as the segmentation variable, especially in the older consumer segment |

| Greco et al (1997) | Influence of older models in advertisements and its effect on sales | • Age of the model does not affect the consumers' attitudes toward an age-free product |

| Day & Stafford (1997) | Tries to understand how consumers react to older age cues in advertising | • Consumers' response towards ads not affected by the older age cues for less conspicuous services while negative influence was found for more conspicuous services |

| Speck & Elliott (1997) | Examines the consumers' avoidance of advertisements in different media platforms and the impact of different demographic variables | • Demographic variables like income and age influenced consumers' avoidance of advertisements |

| Carrigan & Szmigin (2000) | Identifies the problems related to the representations of older people in advertising | • Proposes a framework for better representation and portrayal of older consumers in ads |

| Fung & Carstensen (2003) | Age differences in preferences and memory of ads based on socio-emotional selectivity theory | • Consumers’ memory of persuasive messages is affected by the realisation of emotional goals. Time perspective also influences age differences in consumer responses to ads |

| Phillips & Stanton (2004) | Determines the extent to which age-related differences in recall and persuasion affect perceptions of advertising | • Finds that younger consumers recall more and are persuaded less whereas for older consumers the reverse is true contradicting existing findings |

| Williams & Drolet (2005) | Differences in response to emotional ads influenced by age | • Emotional ads, especially negative emotions, are more preferred by older respondents •Moderating influence of time horizon perspective in consumers’ preference for ads |

| Moschis & Mathur (2006) | Examines the influence of subjective age on consumers' response to age-segmented marketing stimuli and age-related stereotypes | • Significant impact of subjective age and age-related self-concept on consumers' response to different marketing communication cues |

| Weijters & Geuens (2006) | Evaluation of age-related labels by older consumers | • Identifies different age-related labels that can be effectively used and that need to be avoided in marketing communications |

| Drolet et al., (2007) | Investigates age-related differences in response to affective vs. rational ads and the role of product category | • Product category does not influence older consumers’ attitudes toward ads whereas young adult consumers favored affective ads only for hedonic products and rational ads for utilitarian products |

| Te’eni-Harari et al. (2007) | Test whether Petty and Cacioppo’s ELM Model is relevant to young people | • Age influences the route of persuasion for ad processing in consumers. Product involvement variable determines the route of persuasion only in adults and not in young consumers |

| Chang (2008) | How the perceived age of advertising models and consumers, influence their responses to advertising. | • Age of the model is used as a cue for self-categorization •High congruency between the model’s perceived age and the consumers’ cognitive age predicted higher degrees of “for-me” perceptions and positive attitude towards ad |

| Te’eni-Harari et al. (2009) | Investigate the role of the product involvement variable in advertising information processing among young people | • Indicate the effect of age group and product involvement variable on ad effectiveness |

| Micu & Chowdhury (2010) | Explores the consumer response to various ad appeals and the influence of time horizon perspective in the relationship | • Older adults favourably reacted to prevention versus promotion focus ad appeals in general. |

| McKay- Nesbitt (2011) | Examines how individual characteristics of age, need for cognition, affective intensity interact with each other and with advertising appeals to influence ad attitudes, involvement, recall. | • Age significantly affects the recall of emotional ads in younger adults. It also influences the preference of the type of appeal in older adults but does not affect the ad attitude of younger adults. Age interacts with affective intensity to influence ad attitudes across appeal frames |

| Chevalier & Lichtlé (2012) | Determines the effect of the perceived age of the model shown in an ad on different variables about the advertisement’s effectiveness like attitudes, beliefs, and purchase intention on consumers of different age groups | • Finds that similarity between the model’s age and the subjective age of the respondent will allow greater advertising effectiveness. |

| Hoffmann et al. (2012) | Tries to formulate a better way to target mature consumers in ads based on the perceived similarity between the respondent and the model ad | • Introduces the constructs of modesty and activity related to and how it affects the fit between the models’ appearance and consumers’ self-concept which significantly impacts consumers’ response towards the ad |

| Huber et al. (2012) | Links findings from research on different age types to branding literature, and adds insight into rejuvenating a brand through the age of endorsers | • Display of the endorser and the brand together in an advertisement leads to a transmission of associations concerning the endorser's characteristics, like age, to the perception of the brand. The fit between the endorser and the brand also determines the strength of the association |

| Moschis (2012) | Proposes theoretical and methodological bases to analyse the behaviour of older consumers | • Outlines inadequacies of existing approaches to understand the behaviour of older consumers and presents life course paradigm, a popular multi-theoretical approach as a way to address issues in studying the behaviour of older consumers. |

| Wolf et al. (2014) | Investigates how older consumers respond to age-based marketing stimuli | • Identification of the social groups and consumers’ cognitive age has a significant effect on older consumers' response to marketing stimuli. |

| Pezzuti et al (2015) | The effects of advertising models for age-restricted products and self-concept discrepancy on advertising outcomes among young adolescents | • Adolescents facing discrepancies between their actual self and ideal self try to mitigate by conforming to ads with young adult models for age-restricted products and associating the product with their ideal self |

| Roy et al. (2015) | Explores the effect of celebrity -consumer age congruency on consumers' evaluation of ads | • Celebrity-consumer age congruency positively impacts consumers’ evaluations. •Identifies moderation effect of celebrity-product congruency. |

| Sharma (2015) | Study on how age impacts the responses to different communication cues and which age groups respond more favorably to a given cue. | • Significant variances were observed in consumer attitudes across the different age groups for different communication cues in which the product information cue was most effective for older adults. The variation also differed across product categories. |

| Teichert et al. (2018) | Offers a framework for the appropriate choice of advertising appeals for the relevant marketing objectives | • Consumers’ age and gender significantly influenced the effects of advertising appeals, especially for emotional ads |

| Albouy & Décaudin (2018) | Study age differences in responsiveness to shocking prosocial campaigns | • Consumers’ response to emotional campaigns, especially for higher emotional ads influenced by age and self-efficacy moderates the relationship |

| Chevalier & Moal-Ulvoas (2018) | Older consumers' response to mature models in ads in the context of their spirituality | • Identifies ageing as a biological and psychological process and suggests how to target older consumers through ads by addressing their spiritual needs |

| Chan and Fan (2020) | Investigate how older consumers perceive advertisements with a mature celebrity endorsement | • The consumers in Asian markets did not identify negative stereotyping of older consumers in advertisements contrary to existing findings since mature adults in Asian advertisements are depicted more positively when compared to Western ads |

| Alhabash et al. (2021) | Influence of age of the model in alcohol advertising among underage minors | • The consumer-model age congruence influences consumers’, especially underage consumers’ affective and cognitive processing and behavioral outcomes, and the effects of consumer-model age congruence in ads vary by consumer segment |

| Branchik et al. (2021) | Understand the influence of generational differences in women's responses to marketing communications | • Age affects the value system of women consumers which in turn influences their response to various marketing communications. Any cultural values expressed in ads have different impacts depending on consumer age. |

| Rosenthal et al. (2021) | Investigates how older consumers interpret advertisements portraying their cohort | • Consumers' strongly rejected overly positive stigmatized images of ageing since they believed that these images misrepresented their self-images, behaviours, abilities, and preferences, reflecting both identity-related and relational concerns towards these images. The concept of ‘liminal state’ identified by older consumers also discussed |

| Eisend (2022) | Presents a review of the existing studies on representations of older consumers in advertising | • Discuss the representation and portrayal of older people in advertising and analyse the response to advertisements featuring older models. |

Conceptual Analysis

Advertising research recognizes age as an important demographic factor that directly influences advertising effectiveness and persuasion in consumers. A systematic review through the existing literature on age or age-related information or messages and its influence on advertisements revealed that the following domains were the focus of the majority of the studies

Consumers’ Age on Information Processing and Response to Advertisements

Studies that have focused on the age-related similarities in consumers’ processing of relevant information in advertisements found that the information capabilities of both young and elderly consumers were very similar and their processing deficits are affected by similar variables like task factors (John & Cole, 1986). While exploring consumers’ processing of relevant information in the advertisements, it was found that age had a significant effect on their route of information processes and involvement variable that determines the route of persuasion and thus influences advertising effectiveness (Te’eni-Harari et al., 2007; Te’eni-Harari et al., 2009).

Age significantly affects consumers’ recall and persuasion and influences their response to advertisements (Phillips & Stanton, 2006). Emotional goals in ads influence consumers’ preference and recall and affect their perception of advertising (Fung & Carstensen, 2003). Age interacts with advertising appeal to influence consumers’ attitudes toward ads (Teichert et al., 2018). It also affects consumers’ emotional response toward ads (Stout & Rust, 1993) and their preference of ad appeal (Albouy & Décaudin, 2018). Age and affective intensity influence ad attitudes across different appeal frames. Ad recall and attitude of consumers are affected by ad appeal type which in turn is determined by their age (McKay-Nesbitt, 2011). Age-related differences in consumers’ preference for ad appeal are impacted by the product context in the ad (Williams & Drolet, 2005; Drolet et al., 2007). Consumers’ responses to advertisements in terms of brand attitude and recall are also affected by age (Sharma 2015).

A few studies tried to explain age-related differences in consumers’ processing and responses based on the differences in motivational states and goals (Williams & Drolet, 2005, Drolet et al., 2007) or differences in the value system possessed by consumers of different age groups (Branchik et al., 2021).

Although the review proves that age exerts a considerable influence in determining consumers’ processing of and responses to advertisements, a deeper exploration into different factors like related variations in consumer engagement and attention allocation patterns or age-based differences in consumer responses to different ad contexts is lacking in the existing literature.

Age-Related Cues and Consumers’ Response

The majority of studies dealing with age-related cues are focused on mature consumers’ response to age-based cues in marketing communications due to the economic importance of that target segment (Moschis & Mathur, 2006; Weijters & Geuens, 2006; Wolf et al., 2014). There is still a lack of clarity on what constitutes age-related cues. The most common description used by studies is that age-related cues are the contextual elements (e.g. age of the model featured in the ad, certain age-related labels, or explicit age specifications) that refer to an older age (Tepper, 1994). Previous research on consumers’ responses to age-based cues in marketing communications provided conflicting observations (Moschis, 2012). In some studies, respondents had negative reactions toward age-based cues which were attributed to factors like self-devaluation, perceived stigma, or threat to self-image evoked in consumers by these age-based cues (Tepper, 1994). Contrary to this, respondents evaluated positively age-related labels in a later study, a deviation explained through the concept of group membership (Weijters & Geuens, 2006). Other factors like chronological age, the interaction of respondents with personal sources, and mass media interaction were related to their orientations toward age-based marketing stimuli (Moschis et al., 1993). Age cues in marketing communications also influenced consumers’ intention to patronize certain establishments (Day & Stafford, 1997). Information on how consumers respond to age-based cues in advertisements is sparse (Wolf et al., 2014).

There exists a lot of ambiguity surrounding the concept of age-related cues. Research is also lacking on how age-related cues are utilized, particularly in an advertising context. The focus of the existing studies is also limited to mature consumer segments even though the perception of age is relevant for all the consumer groups. Thus, a more thorough investigation into the age-related cues and consumers’ perceptions of them in advertisements would bring about more meaningful insights.

Age-Related Cues and Model/Celebrity in the Advertisement

Among the different age cues described by Tepper (1994), advertisers mostly rely on models/celebrities in their advertisements to deliver age-related cues in ads (Greco.,1997; Chevalier & Lichtlé, 2012). Consumers attribute the endorser’s characteristics like age to the product or brand, through transfer of association. This transfer of association is greater when the fit between the endorser and the product/brand is high (Huber et al., 2013). They consider the age of the model as a cue to identify themselves with the situation in the ad and decide whether the ad deserves their attention and elaboration (Chang, 2008). The perceived age of the model in the advertisement affects the cognitive processing of the advertisement by the consumers (Alhabash et al., 2021).

Advertisers use congruence between the age of the model/celebrity and the targeted consumers to influence their ad evaluations and purchase intentions (Chang, 2008; Pezzuti et al., 2015). While many researchers find that a perceived match between the age of the model in the ad and the target consumers produces positive evaluations (Chang, 2008; Chevalier & Lichtlé, 2012; Roy et al., 2015) some others proved that, in certain contexts (e.g. age restricted products or self-concept discrepancy), the target consumers, do not respond positively to similar age models in the ad (Pezzuti et al., 2015; Alhabash et al., 2021). In the case of mature consumers also, studies suggest that their reactions to the similarity in the age of the model in the ad vary, depending on different factors like product/service context, their socio-psychological process of ageing, different cultural factors, their social networks, etc. (Day & Stafford, 1997; Moschis & Mathur, 2006; Hoffmann et al., 2012; Chan & Fan, 2020). A later study showed that older consumers denounced the ‘next younger’ model in the advertisements representing them (Chevalier & Moal-Ulvoas, 2018). Many researchers also argue that the similarity between the perceived age of the model in the advertisement and the target consumers’ age elicits more favorable reactions than the similarity in their actual age (Chang, 2008; Chevalier & Lichtlé, 2012).

Age is a multi-dimensional concept (Chang, 2008). The research on communicating age through models/celebrities in advertisements has not explored these dimensions well. Variances due to different factors like product contexts, changes in self-concept, differences in perception of age by different age groups, etc are not discussed in detail to get better insights. Thus it becomes pertinent to understand more about how to convey age-related information efficiently through advertisements and not limit its focus just to the age of model/celebrity.

Cognitive Age in Advertisements and Consumer Responses

Complexities in communicating age-related cues and information through advertisements paved the way for the concept of cognitive age and its influence on consumers’ response to age-based marketing stimuli (Stephens, 1991; Moschis & Mathur, 2006). Consumers, especially older consumers, perceived themselves as younger than their actual age (Barack & Schiffman, 1981), and thus advertisers prefer a spokesperson who is similar to the cognitive age of the target consumers, rather than their actual age for better attention and evaluation of advertisements (Stephens, 1991).

The research on the influence of cognitive age on consumers’ evaluation of age related labels in marketing communication has conflicting observations, with many studies highlight the importance of cognitive age on consumers’ responsiveness to age-related cues, which varied significantly depending on factors like the type of stimulus and age group considered (Moschis & Mathur, 2006) while others show that it did not significantly influence the evaluations of age-related labels (Weijters & Geuens, 2006). It had a significant impact in determining consumers’ response to the the age of the model/celebrity in the advertisement (Chevalier & Lichtlé, 2012). Cognitive age of the models in advertisements also acted as a cue for self-categorization for consumers’ ad processing and influenced their ad attitude (Chang, 2008). Thus, the concept of cognitive age in advertisements needs a more thorough understanding.

Misrepresentation of Age in Advertisements

A large body of literature explores the dissonance and dissatisfaction of older consumers regarding the representation of age in advertising (Greco.,1997; Carrigan & Szmigin, 2000; Eisend, 2022). The concerns regarding communication age based information to mature consumers in advertisements include under representation, negative portrayal, perpetuating stereotypical ideas about age and aged persons (Carrigan & Szmigin, 2000; Chevalier & Moal-Ulvoas, 2018), unrelatable, overly positive ideal images (Carrigan & Szmigin, 2000) etc. Older consumers found that the mature models in the advertisements were made to look younger than they actually are and call for a representation that is realistic and respectful while being aesthetic (Chevalier & Moal-Ulvoas, 2018). They rejected overly positive stereotyped images of ageing since they believed that these images misrepresented their self-images, behaviors, abilities, and preferences, raising identity-related and relational concerns towards these images. It was found that older consumers remain in the liminal state of ‘not too old nor too young’, where they engage in activities to remain in this state and distance themselves from the cohort whom they consider as worse off due to age (Rosenthal et al., 2021). The only study that deviates from this line of observations is of Chan & Fan (2020) where the participants in the study did not raise the concern of stereotyping or stigmatized images of the older consumers. The authors assume that it may be because mature adults in advertising are described more positively in Asian markets than in Western countries.

The flaws in communicating age-related information to older consumers in advertisements are evident from the existing literature. The responses from the participants from various studies emphasize the need for better strategies to convey age and effectively hold target consumers' attention through advertisements.

Limitations of Age in Advertising Research

Although age has been established as an inevitable concept in the field of advertising research, the confusion and conflict surrounding it have not ebbed. Recent studies have been illustrating the complexities in communicating and processing age in advertisements (Chevalier & Moal-Ulvoas, 2018; Chan & Fan, 2022) or the inadequacy of chronological age in explaining the heterogeneous behavior observed in consumers of the same age group (Oates et al., 1996). Different measures like subjective age were introduced to provide a better explanation to understand consumers’ response to age-based marketing techniques (Moschis & Mathur, 2006; Chang, 2008). One of the main arguments all those studies put forth is that age is a multi-dimensional concept and even people with a similar age, experience it very differently (Moschis & Mathur, 2006; Chang, 2008, Chevalier & Moal-Ulvoas, 2018). Most of these studies are focused on mature consumers due to the economic importance associated with this target consumer segment and age being a concern for this group (Moschis & Mathur, 2006).

Chevalier & Moal-Ulvoas (2018) while investigating older consumers' response to mature models in ads, identifies ageing as a biological and socio-psychological process that has different physical, mental, and social implications for people undergoing the process. These differences may also affect their response to age-related cues in the advertisement. Advertisers’ challenge is to be aware of the physical, psychological, and social role changes that affect consumers due to ageing and their reactions to these changes portrayed in advertisements and adapt the concepts accordingly (Hoffmann et al., 2012).

As observed above, most of these studies are concentrated on mature consumers. But age and its biological and socio-psychological implications apply to consumers of all age groups. It will also affect how they process information related to age in advertisements and their corresponding responses. While the discourses on consumer behavior have been using theories of ageing to explain heterogeneity in consumer responses (Moschis, 2012), advertising research has made very few attempts to understand the different aspects of age and its significance from the consumers’ perspective.

Discussion

The review reveals many relevant findings and meaningful insights on an important but under-researched topic of age or age related information or messages in advertisements. The major research gaps evolved from the study and possible research questions that could be explored in the future are summarised in the table below. The findings are discussed in detail in the later section Table 2.

| Table 2 Research Gaps and Future Research Directions | ||

| Topic | Research gap | Future research directions |

| Consumers’ age on information processing and response | • Lack of research focused on the variations in engagement and attention allocation of consumers due to their age | • What are the age-related variations in the attention span and engagement patterns of consumers across various ad formats and media platforms and contexts • Compare the attention and engagement patterns among digital immigrant and digital native consumers |

| Age-related cues | • Ambiguity related to what are ‘age-related cues’ • Research based on age-related cues in an advertising context lacking |

• What are age-related cues and how they can be integrated into ads specific to an age group of consumers • What are the ethical and cultural implications arising from age-based stereotypes and discrimination while communicating age-based cues • What are the interactive effects of age cues with other demographic factors, such as gender or socioeconomic status, on persuasion. |

| Age portrayal through models in ads | • Sole focus on the similarity between the age of the model and target consumers to convey age | • How different factors like age ambiguity and age perception biases affect consumer perception while comprehending age-related cues through models in advertisements impacting ad effectiveness • How consumers’ reactions to age indications in advertising may be influenced by cultural conventions, values, and attitudes regarding age. • How age portrayal using models or celebrities in non-traditional media channels differ from traditional media |

| Role of various mechanisms in shaping the consumers’ response to age-related cues in ads | • Lack of research on the interactions between age cues and other cognitive processes and mechanisms | • How factors like cognitive load or cognitive fluency and other image attributes, such as attractiveness or congruence to the product or ad affect consumers' perception and response to age-related cues in commercials. • What is the impact of emotional mechanisms, like emotional contagion or emotional priming, on consumers’ reactions to age cues in advertisements. |

Gap 1: Actual Consumer Age on Information Processing and Response

The review finds that age exerts a significant impact on consumers’ processing of information and their responses to advertisements (Fung & Carstensen, 2003; Stout & Rust, 1993; Drolet et al., 2007; McKay-Nesbitt, 2011; Teichert et al., 2018). However, a thorough examination of the patterns and preferences in advertisement viewing behaviour among various age segments as well as knowledge of how different age groups allocate attention to advertisements across multiple media channels are disregarded or absent in prior research.

Here, we suggest the following research axes for future study in this direction. First, it is important to look at future research with a focus on the attention and allocation patterns of consumers throughout the range of ages. Eye tracking is often used in advertising research to analyze its effectiveness, consumer engagement, and persuasion (Lee & Ahn, 2012; Scott et al., 2016). To determine where and how long different age groups pay attention to commercials, for instance, studies can use eye-tracking technology or surveys that show variations in visual fixation patterns and the amount of time spent watching advertisements across media platforms (e.g., TV commercials, online banners, social media ads). Second, a thorough empirical analysis comparing the attention spans of various ad kinds among various age groups is also merited. For instance, younger customers might have shorter attention spans and flip between information more quickly, whereas elderly consumers might pay adverts more continuous attention (Bardhi et al., 2010; Beuckels et al., 2021). Knowing the distinctions can make it easier to modify the formats and substance of advertisements. Third, comprehension of engagement measurement can also reveal information about how interested and receptive people are to marketing. To gauge levels of engagement across various age groups, researchers can use physiological indicators (such heart rate variability) or self-report measures which are commonly used to measure engagement in advertising research (Li et al., 2016; Shen & Morris, 2016).

Ad formats influence consumers’ allocation of attention span to different advertisements, especially in a digital marketing context (Munsch, 2021). Thus there is an urgent need to conduct a thorough examination into how different age groups' attention allocation is influenced by different ad formats. Younger consumers, for instance, might be more open to brief, snappy video ads on social media platforms, while elderly consumers might prefer lengthier, educational commercials on traditional media.

Fifth, in this technological age, consumers of diverse age groups are exposed to commercials via digital media or platforms. Media context has an impact on how people process advertisements (Malthouse et al., 2007; Kwon et al., 2018; Lee & Cho, 2020) and thus it may influence how consumers of different age groups process advertisements. Therefore, we advise further research and investigation to determine how the surrounding material, website design, or program context affects levels of attention and engagement across various age groups. Additionally, careful consideration should be given to comparing attention and engagement patterns between digital immigrants (such as older generations) who acclimated to digital media later in life and digital natives (such as Gen Z and Millennials) who grew up with technology (Kirk et al., 2015).

In conclusion, knowing these disparities across attention allocation and engagement across age groups in various media channels will help marketers create persuasive ad campaigns that appeal to their target demographic. It may result in more effective marketing campaigns and improved interaction with various age groups.

Gap 2: Role of Various Age Cues In Advertisements

The review brought forth a few questions related age related cues in marketing communications. The existing literature on age-related cues in marketing communications is sparse and majorly focuses on understanding the elements that convey age segmentation cues (Tepper, 1994) and consumers’ responses to them (Weijters & Geuens, 2006; Day & Stafford, 1997). The studies on consumers’ responses to age cues in marketing communications also have conflicting findings and do not throw light on how they process these cues (Tepper, 1994; Weijters & Geuens, 2006). Further research should be done to clarify what constitutes an age-related cue, how consumers process it, and how it can be integrated with an advertisement context.

The studies on consumers’ responses to age cues in marketing communications also have conflicting findings and do not throw light on how they process these cues (Tepper, 1994; Weijters & Geuens, 2006). Further research should be done to clarify what constitutes an age-related cue and how it can be defined in advertisements. Generally, age based information is communicated through the models/celebrities featuring in the ad (Chang, 2008; Pezzuti et al., 2015; Roy et al., 2015). This simplistic approach may not be effective in grabbing the attention of the targeted group of consumers. In advertisements, age related cues can also be conveyed in the form of product information (e.g. health products) or through the theme of the advertisement (e.g. life style products). Age also can be conveyed through physiological or socio-psychological perspectives in the advertisements. Thus, a more integrated definition is required for age related cues, especially in an advertising context.

In addition to the above-mentioned research gaps, research in the realm of age cues in advertising has uncovered significant insights, but notable gaps remain, warranting further investigation. Prior literature acknowledges that consumers' responses to age-related cues in marketing communications are influenced by their age group and cognitive processes (Day and Stafford 1997; Weijters & Geuens, 2006). The existing research lacks a deeper understanding of the strategic use of age cues to tailor advertising messages effectively. For example, it would require thoughtful integration of age-related messaging, themes, and product benefits specific to each age group.

Additionally, the literature has not thoroughly explored the differential effects of age cues on distinct age segments, preventing a comprehensive understanding of how age cues can be tailored for targeted marketing. Moreover, ethical implications arising from age-based stereotypes and discrimination remain largely unaddressed in the context of persuasive advertising (Williams et al., 2010). Additionally, it is established that different cultural contexts affect consumers’ interpretation and reception of advertisements (Manceau & Tissier-Desbordes, 2006). However, its effect on age cues in advertising is underrepresented in the literature, despite the potential influence of cultural variations on interpretation and reception. Understanding how culture shapes the persuasive impact of age cues can inform culturally sensitive advertising practices. Although the effects of demographic variables like gender and socioeconomic status on advertising persuasion have been studied (Brunel & Nelson, 2003; Tsai, 2011) little research has examined the interactive effects of age cues with these demographic variables, on persuasion. Investigating these interactive effects will provide valuable insights for refining targeted marketing strategies.

Addressing these research gaps will lead to a more nuanced understanding of the persuasive power of age cues in advertising and facilitate the development of effective and ethically responsible advertising campaigns tailored to diverse consumer age groups.

Gap 3: Age Portrayal through Models in Advertisements

Existing research on age portrayal through models/celebrities in advertisements argue that the similarity between the age of the model/celebrity and the potential consumers increases advertising effectiveness since consumers relate to the situation more and perceive the product/advertisement meant for them (Chang, 2008) but several other concerns are still under researched in this context.

Concepts like age ambiguity and its impact on customer perceptions in advertising have received less consideration. Age ambiguity is when a model or celebrity's age is not immediately apparent in the advertisement, making it difficult for customers to ascertain their exact age (Cook & Kaiser 2004). Consumers may understand and react differently as a result of this lack of clarity, which could have an impact on how effective advertising is. For marketers looking to effectively use age-related indicators, understanding how age ambiguity affects consumer attitudes, emotional reactions, and buy intentions can be quite insightful. Furthermore, there is currently no study on the ideal degree of age ambiguity that appeals to a wider audience while keeping relevance to particular age segments. The complexity of how age is portrayed in advertising will be clarified by filling in this research gap, which will also provide suggestions for creating more inclusive and powerful advertising messages that appeal to a variety of customer age groups.

In addition, little thought has been given on the impact of potential biases, like age perception bias which affect how customers perceive the age of the models or celebrities used in advertising and thereby altering ad effectiveness. Age perception bias research could assist advertisers in making sure that the intended age portrayal matches consumers' interpretations, resulting in more precise and effective advertising messaging. The cross-cultural viewpoints on age depiction in advertising represent another area of research that has to be filled. Consumers' reactions to age indications in advertising may be influenced by cultural conventions, values, and attitudes regarding age (Barak et al., 2001). There is, however, a dearth of study that looks at how age depiction is interpreted differently in various cultural situations. Cultural comparison research can help in developing effective advertising campaigns that are attentive to cultural differences for particular international markets. Since consumers’ responses differ depending on the gender of the model/celebrity in the advertisement (Edwards and La Ferle 2009) it may be possible to identify variances in consumers' preferences for age-related cues depending on the gender of the models or celebrities by looking into how gender interacts with age depiction. Such research might offer helpful pointers for developing commercials that are more inclusive and appealing to a larger audience. Another topic that deserves investigation is the role of age neutrality using celebrities or models in particular product categories. Research is required to determine whether refraining from using overt age cues in advertising using some particular celebrity or model has a beneficial effect on customer responses. Furthermore, it is critical to research how age portrayal using models or celebrities in non-traditional media channels differs from traditional media given the growing popularity of digital media, and how it creates differences in consumers’ processing of the advertisement. Addressing all these gaps helps marketers to create more effective and culturally relevant advertising tactics that connect with a variety of audiences by researching age perception biases, cross-cultural viewpoints, gender-age interactions, age neutrality, digital media influences, and long-term implications of age depiction.

Gap 4: Role of Various Mechanisms in Shaping the Outcome

There are still significant research gaps on intervening mechanisms that call for future study, although the existing literature has examined several systems that influence how age cues affect information processing and response to advertisements. There is, however, a paucity of studies on the interactions between age cues and other cognitive processes, such as cognitive load (Jing Wen et al., 2020) or cognitive fluency (Wang, 2022), that affect how consumers perceive and react to commercials. Customers' reactions to age-related cues are significantly influenced by the context of the product or service (Day & Stafford, 1997). However, little study has looked at how various product kinds (such as utilitarian vs. hedonic) evoke various reactions to age cues. To better customize advertising campaigns for particular product categories, it can be helpful to investigate the connection between product category and age cues.

Additionally, there is a research gap in understanding the role of other image attributes, such as attractiveness or credibility, in moderating the relationship between age cues and consumer outcomes, despite the fact that prior studies have examined the impact of models' or celebrities' age similarity on consumers' responses to advertisements (Chang, 2008; Chevalier & Lichtlé, 2012). The literature has discussed psychological mechanisms like self-categorization and self-referencing (Chang, 2008), but little work has been done to examine the potential impact of emotional mechanisms, like emotional contagion (Hasford et al., 2015) or emotional priming (Yi, 1990), on how consumers react to age cues in advertisements.

By delving into these undiscovered territories, researchers can improve the field of advertising theory and offer marketers useful guidance on how to create more effective and age-specific advertising campaigns.

Conclusion

The review is the first attempt to systematically analyze the existing research on age or age-related cues in advertisements. By doing so, it identifies common themes in the studies, specific patterns, or relationships thereby arriving at key concepts covered through research. The review highlights the importance of age as a concept in advertising research, a need for a better conceptualization of age-related cues or information in marketing communication, especially in an advertising context, and points out the disadvantages of limited focus in existing studies and stresses the need for a better approach. This study suggests a more integrated approach.

The future research directions identified by the review would be beneficial to both academics and practitioners. Pursuing the research directions outlined in the study would address the existing lacunae in the area of study. It would also enrich the theoretical knowledge in advertising research. The directions provided by the study may also provide meaningful insights for practitioners in creating effective advertising targeted to their specific consumer segments. The review also sheds light on the need to nudge advertisers towards a more inclusive, socially conscious advertising strategy without bias or discrimination for the betterment of society as a whole.

Limitations

Although the review attempts to summarize the main topics and variables studied in the existing literature, the study cannot be considered complete. One of the main constraints of the review is the studies included in the review are based on pre-defined inclusion/exclusion criteria and thus the analysis and discussion in the review are limited to those studies only. Another restriction the review encountered was that the studies selected were mostly from a marketing communication perspective, specifically in an advertising context. Age related studies in other fields like gerontology, sociology, socio-psychology etc might have more insights. Most importantly, the review could only address some of the essential questions related to age or age related messages or information in advertisements. This also limits the analytical depth of the review. The review urges the researchers to explore a few of the future research questions and thereby enrich the existing literature.

References

Akhmedova, A., Manresa, A., Escobar Rivera, D., & Bikfalvi, A. (2021). Service quality in the sharing economy: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies. 45(4): 889–910.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Albouy, J., & Décaudin, J. M. (2018). Age differences in responsiveness to shocking prosocial campaigns. Journal of Consumer Marketing. 35(3): 328–339.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Alhabash, S., Mundel, J., Deng, T., McAlister, A., Quilliam, E. T., Richards, J. I., & Lynch, K. (2020). Social media alcohol advertising among underage minors: effects of models’ age. International Journal of Advertising. 40(4): 552–581.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Barak, B., Mathur, A., Lee, K., & Zhang, Y. (2001). Perceptions of age-identity: A cross-cultural inner-age exploration. Psychology and Marketing. 18(10): 1003–1029.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bardhi, F., Rohm, A. J., & Sultan, F. (2010). Tuning in and tuning out: media multitasking among young consumers. Journal of Consumer Behaviour. 9(4): 316–332.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bauer, B. C. 2022. Strong versus weak consumer‐brand relationships: Matching psychological sense of brand community and type of advertising appeal. Psychology & Marketing. 40(4): 791–810.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Beuckels, E., De Jans, S., Cauberghe, V., & Hudders, L. (2021). Keeping Up with Media Multitasking: An Eye-Tracking Study among Children and Adults to Investigate the Impact of Media Multitasking Behavior on Switching Frequency, Advertising Attention, and Advertising Effectiveness. Journal of Advertising. 50(2): 197–206.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Boerman, S. C., Kruikemeier, S., & Zuiderveen Borgesius, F. J. (2017). Online Behavioral Advertising: A Literature Review and Research Agenda. Journal of Advertising. 46(3), 363–376.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Branchik, B. J., Ghosh Chowdhury, T., & Sacco, J. S. (2021). Different women, different viewpoints: age, traits and women’s reaction to advertisements. Journal of Consumer Marketing. 38(6): 614–625.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Brunel, F. F., & Nelson, M. R. (2003). Message order effects and gender differences in advertising persuasion. Journal of Advertising Research. 43(3): 330–342.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Carrigan, M., & Szmigin, I. (2000). Advertising in an ageing society. Ageing and Society, 20(2): 217–233.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cavalinhos, S., Marques, S. H., & Fátima Salgueiro, M. (2021). The use of mobile devices in‐store and the effect on shopping experience: A systematic literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies. 45(6): 1198–1216.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chan, K., & Fan, F. (2020). Perception of advertisements with celebrity endorsement among mature consumers. Journal of Marketing Communications. 28(2): 115–131.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chang, C. (2008). Chronological Age Versus Cognitive Age For Younger Consumers: Implications for Advertising Persuasion. Journal of Advertising. 37(3): 19–32.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chevalier, C., & Lichtlé, M. C. (2012). The Influence of the Perceived Age of the Model Shown in an Ad on the Effectiveness of Advertising. Recherche Et Applications En Marketing (English Edition). 27(2): 3–19.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chevalier, C., & Moal-Ulvoas, G. (2018). The use of mature models in advertisements and its contribution to the spirituality of older consumers. Journal of Consumer Marketing. 35(7): 721–732.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chintalapati, S., & Pandey, S. K. (2021). Artificial intelligence in marketing: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Market Research, 64(1), 38–68.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chopra, I. P., Jebarajakirthy, C., Acharyya, M., Saha, R., Maseeh, H. I., & Nahar, S. (2023). A systematic literature review on network marketing: What do we know and where should we be heading? Industrial Marketing Management. 113: 180–201.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cook, D. T., & Kaiser, S. B. (2004). Betwixt and be Tween. Journal of Consumer Culture. 4(2): 203–227.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Day, E., & Stafford, M. R. (1997). Age-related cues in retail services advertising: Their effects on younger consumers. Journal of Retailing. 73(2): 211–233.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Drolet, A., Williams, P., & Lau-Gesk, L. (2007). Age-related differences in responses to affective vs. rational ads for hedonic vs. utilitarian products. Marketing Letters. 18(4), 211–221.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Du, Y., Hu, X., & Vakil, K. (2021). Systematic literature review on the supply chain agility for manufacturer and consumer. International Journal of Consumer Studies. 45(4): 581–616.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Edwards, S. M., & La Ferle, C. (2009). Does Gender Impact the Perception of Negative Information Related to Celebrity Endorsers? Journal of Promotion Management, 15(1–2), 22–35.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Eisend, M. (2022). Older People in Advertising. Journal of Advertising, 51(3), 308–322.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fung, H. H., & Carstensen, L. L. (2003).Sending memorable messages to the old: Age differences in preferences and memory for advertisements. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(1), 163–178.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gossen, M., Ziesemer, F., & Schrader, U. (2019). Why and How Commercial Marketing Should Promote Sufficient Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Macromarketing, 39(3), 252–269.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Greco, A. J., Swayne, L. E., & Johnson, E. B. (1997). Will Older Models Turn Off Shoppers? International Journal of Advertising, 16(1), 27–36.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Grewal, D., Puccinelli, N., & Monroe, K. B. (2017). Meta-analysis: integrating accumulated knowledge. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46(1), 9–30.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Grove, S. J., & Fisk, R. P. (1997). The impact of other customers on service experiences: A critical incident examination of “getting along.” Journal of Retailing, 73(1), 63–85.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hasford, J., Hardesty, D. M., & Kidwell, B. (2015). More than a Feeling: Emotional Contagion Effects in Persuasive Communication. Journal of Marketing Research, 52(6), 836–847.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hoffmann, S., Liebermann, S. C., & Schwarz, U. (2012). Ads for Mature Consumers: The Importance of Addressing the Changing Self-View Between the Age Groups 50+ and 60+. Journal of Promotion Management, 18(1), 60–82.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hollis, N. (2005). Ten Years of Learning on How Online Advertising Builds Brands. Journal of Advertising Research, 45(02), 255-268.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Huber, F., Meyer, F., Vogel, J., Weihrauch, A., & Hamprecht, J. (2013). Endorser age and stereotypes: Consequences on brand age. Journal of Business Research, 66(2), 207–215.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hulland, J., & Houston, M. B. (2020). Why systematic review papers and meta-analyses matter: an introduction to the special issue on generalizations in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(3), 351–359.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jang, W., Ko, Y. J., & Stepchenkova, S. (2014). The Effects of Message Appeal on Consumer Attitude Toward Sporting Events. International Journal of Sport Communication, 7(3), 337–356.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jebarajakirthy, C., Maseeh, H. I., Morshed, Z., Shankar, A., Arli, D., & Pentecost, R. (2021). Mobile advertising: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(6), 1258–1291.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jing Wen, T., Kim, E., Wu, L., & Dodoo, N. A. (2019). Activating persuasion knowledge in native advertising: the influence of cognitive load and disclosure language. International Journal of Advertising, 39(1), 74–93.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

John, D. R., & Cole, C. A. (1986). Age Differences in Information Processing: Understanding Deficits in Young and Elderly Consumers. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(3), 297.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kirk, C. P., Chiagouris, L., Lala, V., & Thomas, J. D. E. (2015). How Do Digital Natives and Digital Immigrants Respond Differently to Interactivity Online? Journal of Advertising Research, 55(1), 81–94.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kwon, E. S., King, K. W., Nyilasy, G., & Reid, L. N. (2018). Impact of Media Context On Advertising Memory. Journal of Advertising Research, 59(1), 99–128.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lee, J., & Ahn, J. H. (2012). Attention to Banner Ads and Their Effectiveness: An Eye-Tracking Approach. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 17(1), 119–137.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Li, S., Walters, G., Packer, J., & Scott, N. (2017). A Comparative Analysis of Self-Report and Psychophysiological Measures of Emotion in the Context of Tourism Advertising. Journal of Travel Research, 57(8), 1078–1092.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Linnenluecke, M. K., Marrone, M., & Singh, A. K. (2019). Conducting systematic literature reviews and bibliometric analyses. Australian Journal of Management, 45(2), 175–194.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Malthouse, E. C., Calder, B. J., & Tamhane, A. (2007). The Effects of Media Context Experiences On Advertising Effectiveness. Journal of Advertising, 36(3), 7–18.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Manceau, D., & Tissier-Desbordes, E. (2006). Are sex and death taboos in advertising? International Journal of Advertising, 25(1), 9–33.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

McKay-Nesbitt, J., Manchanda, R. V., Smith, M. C., & Huhmann, B. A. (2011). Effects of age, need for cognition, and affective intensity on advertising effectiveness. Journal of Business Research, 64(1), 12–17.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Micu, C. C., & Chowdhury, T. G. (2010). The effect of ageing and time horizon perspective on consumers’ response to promotion versus prevention focus advertisements. International Journal of Advertising, 29(4), 621–642.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Morden, A. R. (1987). Elements of Marketing. Letts & Londsale.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Moschis, G. P. (2012). Consumer Behavior in Later Life: Current Knowledge, Issues, and New Directions for Research. Psychology & Marketing, 29(2), 57–75.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Moschis, G. P., & Mathur, A. (2006). Older Consumer Responses to Marketing Stimuli: The Power of Subjective Age. Journal of Advertising Research, 46(3), 339–346.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Munsch, A. (2021). Millennial and generation Z digital marketing communication and advertising effectiveness: A qualitative exploration. Journal of Global Scholars of Marketing Science, 31(1), 10–29.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nguyen, D. H., de Leeuw, S., & Dullaert, W. E. (2016). Consumer Behaviour and Order Fulfilment in Online Retailing: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20(2), 255–276.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Oates, B., Shufeldt, L., & Vaught, B. (1996). A psychographic study of the elderly and retail store attributes. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 13(6), 14–27.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Palmatier, R. W., Houston, M. B., & Hulland, J. (2017). Review articles: purpose, process, and structure. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46(1), 1–5.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Paul, J., & Feliciano-Cestero, M. M. (2021). Five decades of research on foreign direct investment by MNEs: An overview and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 124, 800–812.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Paul, J., Lim, W. M., O’Cass, A., Hao, A. W., & Bresciani, S. (2021). Scientific procedures and rationales for systematic literature reviews (SPAR‐4‐SLR). International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(4).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pezzuti, T., Pirouz, D., & Pechmann, C. (2015). The effects of advertising models for age‐restricted products and self‐concept discrepancy on advertising outcomes among young adolescents. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25(3), 519–529.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Phillips, D. M., & Stanton, J. L. (2004). Age-related differences in advertising: Recall and persuasion. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 13(1), 7–20.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rosenthal, B., Cardoso, F., & Abdalla, C. (2020). (Mis)Representations of older consumers in advertising: stigma and inadequacy in ageing societies. Journal of Marketing Management, 37(5–6), 569–593.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Roy, S., Guha, A., & Biswas, A. (2015). Celebrity endorsements and women consumers in India: how generation-cohort affiliation and celebrity-product congruency moderate the benefits of chronological age congruency. Marketing Letters, 26(3), 363–376.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Scott, N., Green, C., & Fairley, S. (2015). Investigation of the use of eye tracking to examine tourism advertising effectiveness. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(7), 634–642.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Shen, F., & Morris, J. D. (2016). Decoding Neural Responses to Emotion in Television Commercials: An Integrative Study of Self-Reporting and fMRI Measures. Journal of Advertising Research, 56(2), 193.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Siachou, E., Trichina, E., Papasolomou, I., & Sakka, G. (2021). Why do employees hide their knowledge and what are the consequences? A systematic literature review. Journal of Business Research, 135, 195–213.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Speck, P. S., & Elliott, M. T. (1997). Predictors of Advertising Avoidance in Print and Broadcast Media. Journal of Advertising, 26(3), 61–76.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Srivastava, S., Singh, S., & Dhir, S. (2020). Culture and International business research: A review and research agenda. International Business Review, 29(4), 101709.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Stephens, N. (1991). Cognitive Age: A Useful Concept for Advertising? Journal of Advertising, 20(4), 37–48.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Stout, P. A., & Rust, R. T. (1993). Emotional Feelings and Evaluative Dimensions of Advertising: Are They Related? Journal of Advertising, 22(1), 61–71.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Te’eni-Harari, T., Lampert, S. I., & Lehman-Wilzig, S. (2007). Information Processing of Advertising among Young People: The Elaboration Likelihood Model as Applied to Youth. Journal of Advertising Research, 47(3), 326–340.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Te’eni-Harari, T., Lehman-Wilzig, S. N., & Lampert, S. I. (2009). The importance of product involvement for predicting advertising effectiveness among young people. International Journal of Advertising, 28(2), 203–229.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Teichert, T., Hardeck, D., Liu, Y., & Trivedi, R. (2017). How to Implement Informational and Emotional Appeals in Print Advertisements. Journal of Advertising Research, 58(3), 363–379.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Tepper, K. (1994). The Role of Labeling Processes in Elderly Consumers’ Responses to Age Segmentation Cues. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(4), 503.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Tsai, W. H. S. (2011). How Minority Consumers Use Targeted Advertising as Pathways to Self-Empowerment. Journal of Advertising, 40(3), 85–98.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Vakratsas, D., & Ambler, T. (1999). How Advertising Works: What Do We Really Know? Journal of Marketing, 63(1), 26-43.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Vrontis, D., & Christofi, M. (2021). R&D internationalization and innovation: A systematic review, integrative framework and future research directions. Journal of Business Research, 128, 812–823.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Vrontis, D., Makrides, A., Christofi, M., & Thrassou, A. (2021). Social media influencer marketing: A systematic review, integrative framework and future research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(4), 617–644.

Wang, J. (2022). Consumer Anxiety and Assertive Advertisement Preference: The Mediating Effect of Cognitive Fluency. Frontiers in Psychology, 13.

Weijters, B., & Geuens, M. (2006). Evaluation of age-related labels by senior citizens. Psychology and Marketing, 23(9), 783–798.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref