Research Article: 2019 Vol: 25 Issue: 2

African Immigrant Entrepreneurship A Catalyst for Skills Transfer

Bernard Lama Ngota, Walter Sisulu University

Sookdhev Rajkaran, Walter Sisulu University

Eric E. Mang’unyi, Catholic University of Eastern Africa

Abstract

Predominantly, the role and importance of African immigrant entrepreneurship had been rarely elaborated with perspectives to its contribution on skills transmission. This study examines African immigrants’ entrepreneurial activities in South Africa, how their entrepreneurial practices lead to skills transmission to their employees in general and South Africans in particular. Therefore this paper aimed at assessing the contributions made by African immigrant entrepreneurs’ towards skills transmission in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa which is perceived to be missing amongst the locals. Understanding these components is vital for stakeholders and the government as this area plays a major role towards skills development and job creation. Pragmatic research paradigm was adopted and a mixed method was selected. Data was obtained from 170 entrepreneurs and their employees through questionnaire and semi-structured interviews formed the basis for the analysis. Descriptive and content analyses were employed to analyse data. The results of the study revealed that immigrant Small, Medium and Enterprises (SMEs) contribute towards skills transmission to the locals. Adaptive governmental policies thus require a holistic appreciation of the African immigrants’ contributions to entrepreneurial skills transmission which stimulate economic growth and new business opportunities.

Keywords

Skills Acquisition, Entrepreneurial Skills Transfer, South Africa, Entrepreneurship, Immigrant Entrepreneurship, Employees.

Introduction

Immigrant enterprise has been distinguished for impacting new skills and the introduction of new business ventures development which correlates positively with a country’s economic output (Kalitanyi & Visser 2010a:2010b:2014; Fairlie, 2012; Ngota et al., 2017). Some authors (Letseka & Maile, 2008; Khosa & Kalitanyi, 2014), pointed out that, with a 15% college graduation rate which is one of the most minimal on the planet, South Africa still faces a tremendous challenge with regards to providing the fundamental abilities in numerous fields. This has not exclusively been witness in zones such as normal sciences, technology and in engineering however it is additionally a reality in some sociologies division, for example, business enterprise, which has affected the administration activities for job creation (Fatoki & Patswawairi, 2012). This study agrees with the aforementioned results and allude that skills such entrepreneurial skills which have the ability to create jobs and reduce unemployment as well as improving the standards of living of the locals are deficient amongst the nationals. According to O’Neill & Viljoen (2001), entrepreneurs may be considered as the most imperative criterion for economic development in a country, and without them, the state has the difficult task of organising development without the motivating force of potential gain.

Cazes and Verick (2013) theorize that human capital paradigm adopts that everything being equal, the number of years spent in schooling system escalates one’s capacity to get a job. Further, Van de Rheede (2012) however argued that the nature of unemployment of skilled workers is a complex one, since it relates to various factors such as the value of education, lack of experience, discrimination and labour market inflexibility, labour legislation as well as other structural parameters. Researchers (Bogan & Darity, 2008; Khosa & Kalitanyi, 2015; Crush et al., 2017) posit that, with such aforementioned constraints, it is difficult for immigrants to enter into the labour market therefore, entrepreneurship becomes a better option. In that way, they create skills opportunity for others.

As such, some authors (Chamuorwa & Mlambo, 2014; Asoba & Tengeh, 2016; Ntema 2016; Ngota et al., 2017) attest that South Africa has had colossal development over years and as such, is counted to be one of the largest economies on the African continent. In their study on migration and migrants entrepreneurial skills in South Africa, (Kalitanyi & Visser, 2014) established that African immigrant entrepreneurs transmit their entrepreneurial skills to local nationals. The findings of their study uncovered that more than 73% of immigrant entrepreneurs who took part in their survey authenticated of transmitting their entrepreneurial skills to locals who are either employed by them or do business with them (Kalitanyi & Visser, 2014). Moreover, the study also revealed that 82% of the immigrant entrepreneurs’ employees are locals, of whom 54% have ascertained to have acquired entrepreneurial skills from their employers (Kalitanyi & Visser, 2014). This correlate with the study by some authors (Cross 2006; Kalitanyi & Visser, 2014) who alluded that immigrant entrepreneurs, who mostly survive by their entrepreneurial initiatives in order to satisfy their essential needs, claim to encourage local people.

From the aforementioned above, the presence of numerous African immigrants in South Africa, and their participation in small business activities, continues to attract diverse social organizations and scholars alike to examine the magnitude to which their entrepreneurial accomplishments benefit their employees in general and the local citizens in particular. This study is in response to the hostile economic environment in South Africa towards immigrants and immigrant entrepreneurship, especially African immigrant entrepreneurship where ordinary people are becoming more and more intolerant, exhibiting destructive and sometime brutal attitude towards these immigrants while making all sorts of detrimental comments and looting of their businesses. Data reports shows a high rate of unemployment in South Africa which stood at 27.1% at the last quarter of 2017 (StatsSA, 2017). This report therefore portrays the current economic situation of South African. Undertaking this study aimed at bringing to the fore the entrepreneurial contribution towards skills in alleviating the unemployment problem through the creation of new SME ventures. In this respect, insufficient knowledge of the economic opportunities and contributions African immigrant entrepreneurs make towards skills transfer and skills development in their host countries, has always led to countless adverse perceptions and negative attitudes towards immigrants. Since 2008, there has been a series of violent attacks on immigrants inhabiting South Africa, with African immigrant businesses being the primary target. In the light of the above, one will be compelled to ask if African immigrants’ entrepreneurship really lead to economic contribution such as entrepreneurial skills transfers in their host countries such as South Africa that could help curb the unemployment issues. Hence, understanding how these immigrants’ entrepreneurial skills are transferred, which can create economic opportunities through their entrepreneurial ventures in South Africa and the Eastern Cape in particular is worth investigating, as this will create awareness for coexistence in the communities that these immigrants are operating their businesses.

In view of the above discourse, it is eminent to this study to scrutinize implications of immigrant-owned businesses for skills transfer and employment opportunities. In epitome, the paper argues that immigrant entrepreneurs, particularly Africans have had a positive effect on the local socio-economy. In order to examine the involvement of African immigrant enterprises to skills transfer, this paper begins with the objectives, a brief literature review on the theories anchoring this paper, followed by a discussion on immigrant entrepreneurship and skills transfer. It then highlights the methods and empirical evidence from the survey and interviews; finally, the paper concludes by illustration out the implications of findings for South Africa.

Study Objectives

Against the aforementioned background above, this paper endeavours to center on the entrepreneurial skills contributions that African immigrant entrepreneurs make to their employees in South Africa. Arguing that the skills contribution process by African immigrants are in response to delicate entrepreneurial skills challenges they face as well as the salient entrepreneurial characteristics they possess, the following two sub-objectives are formulated:

1. To identify the medium through which immigrant entrepreneurial skills are transferred to their employees.

2. To establish if African immigrant entrepreneurs are willing to share the entrepreneurial skills with their employees and the reasons why they are willing to do so.

This article is presented in the following format: in the next section, literature on skills acquisition, immigrant entrepreneurship is reviewed, skills transfer, followed by the theoretical framework for the study. Further, the methodology employed to carry out the research as well as the presentation of the results and their discussions. In the final section, recommendations and concluding remarks are presented.

Literature Review

The literature on immigrant entrepreneurship in general and immigrant entrepreneurial skills transmission in particular, is inconsistent as well as inconclusive. Although small business and entrepreneurship in general have been widely researched in both the developed and less-developed countries, this cannot be said of immigrant-owned businesses in the latter. Limited studies carried in South Africa have endeavored to address how African immigrant entrepreneurial skills are been transferred to their employees (Kalitanyi & Visser, 2010a:2010b).

In the recent field of immigrant and ethnic entrepreneurship, there are a variety of theories or explanations for the rate of entrepreneurialism amongst immigrants. This study was anchored on (Waldiger et al., 1990) model on immigrant entrepreneurship and the Speelman (2005) principles of skills acquisition theory.

The premises of the skills acquisition theory according to Speelman (2005) states that skill acquisition is a form of learning where "skilled behaviours can become routinized and even automatic under some conditions". In other words, this theory assigns roles for both explicit and implicit learning which claims that adults commence learning something through largely explicit processes, and with subsequent sufficient practice and exposure, move into implicit processes. Development, within this theory, entails the utilization of declarative knowledge followed by procedural knowledge, with the latter automatisation (Vanpatten & Benati, 2010). According to Speelman (2005) an individual reaches the stage of automaticity when they can perform routine activities effortlessly and quickly, with little conscious thought or mindfulness. As African immigrant entrepreneurs work with their employees on a daily basis, skills can be conceptualized as large collections of automatic processes and procedures, which make automaticity an important component of skill acquisition (Richard & Schmidt, 2010; Speelman, 2005). In this way, immigrant entrepreneurial employees through these principles transmit their business skills to their employees who through these values acquire new skills and knowledge in their daily and routine tasks in the course of their employment (Richard & Schmidt, 2010).

Waldiger et al. (1990) theory points that opportunity structure portrays the economic situations under which the immigrant organisations work, i.e. the economic situations which may support favour products or services orientated to co-ethnics or to the non-ethnic market. The simplicity with which immigrant entrepreneurs access business opportunities is exceptionally subject to the level of inter-ethnic competition and state policies. For instance, in South Africa, the previous decade has seen forceful rivalry between native-born venture operators and businesses ran by African migrants. Additionally, the perception is that immigrant owned businesses tends to thrive. In such circumstance, this study unveil as to whether businesses operated by immigrant entrepreneurs play a role in the South Africa economic especially in the area of entrepreneurial skills development and transfer. According to Waldiger et al. (1990) model on entrepreneurial perspective of skills acquisition, it has been noted (Aaltonen & Akola, 2014) that through interaction among immigrant entrepreneurs and host entrepreneurs, the former are able to gain new skills in entrepreneurship. The resilient point of this theory is that it provides a broader picture of how immigrants explore their host environments by learning the new environment and their employees acquiring new skills in the process and duration of their employment and continuous working with their immigrant entrepreneur employers. Hence, it fits this study because it allow to scientifically examining the role and importance of immigrants’ entrepreneurship in host countries in employment creation and skills transmission (Habiyakare et al., 2009; Kalitanyi & Visser, 2014; Ngota et al., 2017).

Speelman's (2005) theory on skills acquisition has previously explained how skills are transmitted or acquired within an organisation or in a societal setup and clarifies how skills can be acquired though not specifically entrepreneurial skills. Applying this concept on entrepreneurship in general and immigrant entrepreneurs in particular will add to the scarce literature on skills transfer. Waldiger et al. (1990) model was developed and tested in the western world, to be specific in a developed country and on immigrant entrepreneurship in the USA. It found that immigrant entrepreneurship played a significant role to the western economic through employment creation, competition and the development of new businesses. As these theories put immigrant entrepreneurship on the spot light by explaining immigrant entrepreneurial access to opportunities, group characteristics, and emergent strategies, also, how skills are transmitted and acquired by individual or groups (their employees) makes it suited for this study.

Skills Acquisition

Different authors in different discipline such as the field of psychology have defined skills in different ways. One such author is Speelman (2005) who defined skills acquisition as a form of prolonged learning about a family of events. Speelman (2005) posit that skill acquisition can be considered as a specific form of learning, where learning has been defined as "The representation of information in memory concerning some environmental or cognitive event". Moreover, Speelman (2005) added that the range of behaviours that can be considered to involve skill acquisition could potentially include all responses that are not innate. In the same light, Vanpatten & Benati (2010) states that, "Skill refers to ability to do rather than underlying competence or mental representation". To clarify this concept further, Cornford (1996) elucidated that there are nine separate defining attributes of "skill" and "skilled performance" from a psychological perspective, and argued to be the most valid in accounting for skill acquisition and performance by individuals. The researcher argues that individuals learn values, attitudes, information and skills in their interactions with a corporation with strong entrepreneurial ties. Strong ties with business-related knowledge, skills and experience also provide access to specific information and resources that are necessary for business start-ups. The values, attitudes, information and skills gained from immigrant entrepreneurship strong ties contribute towards increased entrepreneurial intention.

The Concept of Immigrant Entrepreneurship

Immigrant entrepreneurship is the demonstration of moving into a new nation out of the country of origin to establish or carry out a business venture (Dalhammar, 2004; Ngota et al., 2017). Some researchers (Dalhammar, 2004; Fatoki & Patswawairi, 2012; Khosa & Kalitanyi, 2015) postulated that, immigrant entrepreneurship is designated as the process by which an immigrant builds a business in a host nation (or country of settlement) which is not the immigrant’s country of origin. Immigrant entrepreneurship also refers to the entrepreneurship of recent migrants by means of founding a business enterprise or engaging in self-employment. In line with this, some authors (for instance Vinogradov, 2008; Kahn et al., 2013; Aaltonen & Akola, 2014) have stated that, an immigrant entrepreneur is that individual who has immigrated to a different nation, although lacks the host country’s citizenship status, but establishes a business in that nation for economic purposes. Immigrant entrepreneurship concept has become an important socio-economic singularity, as it plays a critical role in economic development. Ngota et al. (2017) authenticates that, this endeavour creates jobs through new business ventures that contributes to wealth creation in the host country.

Ethnic entrepreneurship is generally regarded as equivalent to “Immigrant entrepreneurship” and the two terms are often employed interchangeably, though a slight difference between the two terms exists (Volery, 2007; Azmat, 2010; Khosa & Kalitanyi, 2014). Chand & Ghorbani (2011) define ethnic entrepreneurship as a set of connections and regular patterns of interactions among people sharing a common national background or migration experience. According to Azmat (2010) and Volery (2007), “Immigrants” include the individuals who migrated over the past decades and exclude members of ethnic minority groups who have been living in the country for centuries; the term “ethnic” is a much broader concept and includes immigrants or minorities. Tengeh et al. (2012) alluded that the term “Minority entrepreneurs” is also employed to describe immigrants who carry out entrepreneurial activities. Minority entrepreneur thus refers to business ownership by any individual who is not of the majority population (Khosa & Kalitanyi, 2014). Hence, ethnics are likely to be more recognizable and integrated into host country environment than immigrants (Volery, 2007). Immigrant entrepreneurship thus refers to the early stages in the process of ethnic entrepreneurship (Azmat, 2010).

As elucidated from the aforementioned above, from the researchers own view, the term African immigrant entrepreneur refers to an individual from the African continent that carries out entrepreneurial activities in his or her host county. Therefore, in the current study all four terms (immigrant entrepreneur; ethnic entrepreneur; minority entrepreneur; African foreign entrepreneur) will be used interchangeably. Our explanation includes those individuals who employ themselves as well as those who employ also others.

Entrepreneurial Skills Transfer

A substantial quantity of research has consistently found that business ownership is higher among the foreign-born than the native-born in many developed countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia (Borjas, 1994; Clark & Drinkwater, 2000; Lofstrom, 2002; 2017; Schuetze & Antecol, 2007; Fairlie et al., 2010). Immigrants in the United States are also found to be more likely to start businesses than the native born (Fairlie, 2008). There is evidence of broader contributions by skilled immigrants to innovation. For instance, Hunt & Gauthier-Loiselle (2010) found that the increase in the share of the U.S. immigrant population with at least a college degree increased the country’s patents per capita by about 21 percent. Importantly, they point out that their analysis does not suggest that immigrants are innately more able than the native born but that the higher rate of patenting among college graduate immigrants is entirely explained by the greater share of immigrants with science and engineering education compared to the native born. Another significant study, by Kerr & Lincoln (2010), evaluates the impact of high-skilled immigration on technology formation as measured by science and engineering employment and patenting. They found that high-skilled temporary workers from India and China on H-1B visas in the United States account for a significant share of the growth in U.S. immigrant science and engineering employment. A key takeaway is that the growth is accomplished without crowding out native-born scientists and engineers.

Waldiger et al. (1990) posit that, business-relevant skills and training are often acquired through an apprenticeship in another co-ethnic’s shop. As one Dominican garment factory owner in New York pointed out, “I worked mainly for other Dominicans. I think that it is easier to get ahead if you work for a compatriot” (Waldinger, 2002). In fact, three of every ten Hispanic garment factory owners surveyed in New York had previously worked for another Hispanic, and, of those with supervisory experience, two-thirds had been employed in immigrant-owned firms (Waldinger et al., 2002).

Moreover, Waldiger et al. (1990) theorized that, working for a small ethnic firm allows immigrants to learn nearly all aspects of business management, a goal that entry-level workers in large native-owned firms can rarely attain (Mabadu, 2014). Thus co-ethnic employees’ participation in management is possible not only because of co-ethnic trust but also because of small firm size. Thus the expansion of immigrant businesses in an ethnic community provides both a mechanism for the effective transmission of skills and a catalyst for the entrepreneurial drive (Waldinger, 2002). From the standpoint of immigrant workers, the opportunity to acquire managerial skills through a stint of employment in the immigrant firms both compensates for a low pay and provides a motivation to learn a variety of different skills.

Immigrants who migrate to South Africa are very skilled and some of them come with artisan skills, entrepreneurial skills, and managerial skills giving them the ability to manage and grow up business ventures in their host destinations (Asoba & Tengeh, 2016). Therefore these immigrants help to reduce the skills gap even if not enough (Smith & Watkins, 2012). There is no tradition in Southern Africa on how to teach young children to become entrepreneurs from a young age, unlike in some western African countries. Hence, migrants bring these skills with them and when they employ South Africans in their businesses, they pass on the skills that are missing in indigenous cultural behaviours. This is consistent with a study conducted by Cross (2006), who noted that small businesses in the informal category where there is migrants mentoring, seem to be most effective, far-reaching and quickest skills-training program.

Research Methodology

Research Outline

The present study utilized blended techniques approach which intentionally analyzes or joins strategies for various kinds (qualitative and quantitative) to give a more particularized comprehension of the phenomenon of interest and to increase better independence in the ends created by the investigation (Johnson et al., 2007; Creswell, 2014). Further, the study exploited descriptive and explorative researches since it was addressing the main research question which was “how does African immigrant entrepreneurial skills transferred to their South African employees”. Zikmund et al. (2010) insinuated that engaging exploration illustrates characteristics, individuals, gatherings, associations or environments. While exploitative research strived to gain deep insights from the respondents’ thoughts on the issue under investigation. Consequently, descriptive research endeavours to address who, what, when, where and how inquiries of research. Though the qualitative research is not without its challenges such as limited sample size, the researchers improved the quality of the data by triangulation

Directed Populace

The study targeted all African immigrant entrepreneurs (owners-managers) owning and operating their SMEs in the Eastern Cape Province and their employees. Dorsten & Hotchkiss (2005) recommended that a populace ought to be characterized to involve people we need to depict not simply the individuals who restore a survey. Further, some authors (Zikmund et al., 2010) trust that the unit of examination for an investigation demonstrates what or who ought to give the information and at what level of accumulation. Henceforth, African foreign entrepreneurs (owners-managers) who are operating micro-enterprise in the Eastern Cape Province as well as their South African employees were the unit of analysis as they would provide required and relevant responses for the study.

Sample Size and Selection Technique

The sampling techniques employed in this study were simple random and snowball sampling techniques (which are both probability and non-probability sampling) were utilized to select participants for the study. Study participants were drawn from a population of all African immigrant entrepreneurs (owner-manager) owning SMEs in the Eastern Cape and their employees (this was for them to affirm if there was skills transfer). The researchers achieved this through records obtained from the Business Support Centres and immigrant ethnic associations. The researchers collected some data from some participants through referrals. With the above database as a sampling frame, the researchers used a random sample and snowball by referral to select 170 participants for the study. Out of participants, 153 were owners-managers were selected to complete the questionnaire responses and 17 participants (employees) were selected to take part in the personal interviews. Random sampling is advantageous as it represents the target population and eliminates possible sampling bias, though difficult to achieve most often. The researchers employed snowball sampling in certain part of the study areas (towns) for interviews since immigrant employees’ database were not established.

Study Tools and Data Gathering

The strategy used to do the investigation was an overview by methods for survey. One set of semi-structured questions were developed for African immigrant entrepreneurs’ employees’ interview. The questionnaires were pilot-tested to ensure clarity, comprehension and ease of use. These instruments were utilized for collecting data measuring the respondents’ characteristics, the types of businesses they run, the choice of business locations as well as the businesses with high turnovers. A set of questions to the immigrant entrepreneurs (owners-managers) to measure the transmission of entrepreneurial skills to the local employees was included in the questionnaire. Also, the researchers included a set of questions to the South African employees to measure the level of entrepreneurial skills transmission in the interview questions to complement the survey data. The questionnaire consisted of 15 questions made up of both scale and nominal data addressing the different objectives. The questions were not all Likert scaled except for two sets of the questions. Meanwhile, 11 follow up questions were included for the personal interview.

The researchers printed and self-administered one hundred and sixty questionnaires to participants. A total of 153 completed questionnaires were achieved. This gave an overall response rate of 95.6%. In the same way, the researchers conducted a face-to-face semi-structured interview with African immigrant employees (respondents) at the respondent’s business premise; this was to establish whether truly entrepreneurial skills are being transferred from their immigrant employers to them. Proceeding to the interviews, the researchers made appointments with interviewees (employees) on an agreed upon date and time for the interviews to be conducted after being referred to. Interviews took between 15 and 30 minutes, thereafter, transcriptions were done within the first week after they were first recorded by the researchers. Data collection period was between the months of July to September 2016.

Validity and Trustworthiness

Content validity was maintained as the instrument and interviews were aimed at only achieving the objectives of the study and nothing more (Zikmund et al., 2010). The current study relied on similar researches about the positive impact of immigrants on local South Africans, and since the sample was drawn from a diverse of origins of immigrants from African continent, criterion validity is maintained. The researchers correlated with other standard measures of similar constructs in the questionnaire used ensuring criterion validity. Furthermore, to ensure clarity, correct wording and comprehension of instructions, as well as the easy use of the questionnaire, a pilot study was undertaken, thereby maintaining construct validity. Also, after the researcher transcribed the interview audio recordings, it was taken back to the participants for validation and comments on the interview transcript, whether the final themes and concepts created adequately reflected their responses-this was to ensure trustworthiness. Data from interviews were meticulously kept and the researchers ensured that interpretation of the data was consistent and transparent. After, the interpretation of the data, it was given to the research committee for a review at a manuscript writing workshop event to reduce bias. The researchers assessed internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient on the data obtained by testing the questionnaire and it yielded 0.72, indicating good internal consistency. It measured the frequency of sharing entrepreneurial skills with their employees in different businesses. Due to the sampled sized reached for qualitative data, the researcher complemented this limitation by using mixed methods which gave the stud a chance for data triangulation in order to assist to produced more comprehensive set of findings.

Data Analysis

The survey data were screened, checked and codes assigned to each criteria, thereafter, they were inserted and analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows version 22 (SPSS). Chi-square which which is a proportion of centrality was utilized to decide where used to decide if the distinctions watched were huge. While the interviewed data was analysed thematically to ensure that the participants’ responses were tied to respective objective themes. The researchers presented qualitative findings in abundant and dense verbatim descriptions of participants’ accounts to support research findings.

Ethical Concerns

The researchers thought about every moral prerequisite of an examination while directing the investigation. Permission was sought from the relevant authorities’. Composed educated assent was obtained from all members without pressure. Data collected were kept securely and word verbatim quotes were used from the interviews, no reference was made to participants’ names instead codes/pseudo names were used to maintain confidentiality (Leedy & Ormrod, 2010). Ethics as pertains publishing are also adhered to.

Empirical Findings And Discussions

Profile of the Participants

According to the results (Table 1), 32.7% of the entrepreneurs were males who were involved in services business, 40.5% of the entrepreneurs who were involved in services business were between 31 and 40 years of age while 1.3% of the African immigrant entrepreneurs between the age of 51 and 60 years old were into trading business. Majority of the entrepreneurs 22% who were involved in trading business were from Nigeria. The analysis obtained a computed χ2 value of 119.789, with 22 degrees of freedom and a ρ-value of 0.001, suggesting up to 95% chance that country of origin and form of business ownership were significantly associated. These were followed by 20.9% of entrepreneurs from Cameroon who were involved in services business and Ghana 13.1%. While 0.7% who were involved in trading and services businesses came from other1 countries such as Kenya and Zimbabwe respectively. 34% of the entrepreneurs who were involved in services businesses have stayed in South Africa for between 5 and 10 years, followed by 14.4% of the entrepreneurs who are into trading business have lived for between 11 and 15 years in South Africa.

| Table 1: Profile Of Participants | |||||||

| Profile of participants | Type of industry involved | Summary of Chi-square tests | |||||

| manufacturing | trading | service | Total | Computed X2 | df | p-value | |

| Gender Male Female Total |

8 (5.2) 0 |

49 (32) 15 (9.8) |

50 (32.7) 31 (20.3) |

107 46 153 |

7.371 | 2 | 0.025 |

| Age <20 21-30 years 31-40 years 41-50 years 51-60 years Total |

0 0 5 (3.3) 3 (2) 0 |

0 10 (6.5) 38 (24.8) 14 (9.2) 2 (1.3) |

1 (0.7) 8 (5.2) 62 (40.5) 10 (6.5) 0 |

1 18 105 27 2 153 |

10.974 | 8 | 0.203 |

| Country of origin Nigeria Cameroon Ethiopia Ghana DRC Senegal Uganda Malawi Others Total |

1 (0.7) 0 1 (0.7) 2 (1.3) 0 0 0 3 (2) 1 (0.7) |

34 (22.2) 9 (5.9) 4 (2.6) 5 (3.3) 4 (2.6) 4 (2.6) 2 (1.3) 0 2 (1.3) |

19 (12.4) 32 (20.9) 0 20 (13.1) 9 (5.9) 0 0 0 1 (0.7) |

54 41 5 27 13 4 2 3 4 153 |

119.789 | 22 | 0.000** |

| Duration of stay in SA <5 years 5-10 years 11-15 years >15 years Total |

0 4 (2.6) 4 (2.6) 0 |

12 (8.5) 28 (18.3) 22 (14.4) 1 (0.7) |

11 (7.2) 52 (34) 13 (8.5) 5 (3.3) |

24 84 39 6 153 |

14.085 | 6 | 0.029 |

| Years’ of operation <5 years 5-10 years 11-15 years 16-20 years >20 Total |

1 (0.7) 4 (2.6) 3 (2) 0 0 |

19 (12.4) 36 (23.5) 8 (5.2) 1 (0.7) 0 |

18 (11.8) 50 (33.7) 10 (6.5) 1 (0.7) 2 (1.3) |

38 90 21 2 2 153 |

7.008 | 8 | 0.536 |

| Level of education Less than high school High school certificate Vocational/technical cert. Uncompleted University Bachelor’s degree Master’s degree Total |

1 (0.7) 3 (2) 3 (2) 1 (0.7) 0 0 |

5 (3.3) 34 (22.2) 11 (7.2) 9 (5.9) 4 (2.6) 1 (0.7) |

6 (3.9) 51 (33.3) 9 (5.9) 6 (3.9) 9 (5.9) 0 |

12 88 23 16 13 1 153 |

9.793 | 10 | 0.459 |

Note: **represents significance at 0.05 error margin; Figures in brackets represents percentages.

Source: Computed from survey results 2016.

The Table above further revealed that 33.7% of the entrepreneurs have been involved in the services business for between 5 and 10 years while 0.7% has been involved in the manufacturing and trading businesses respectively. Majority (33.3%) of the entrepreneurs involved in services business had attained a high school certificate, followed by 7.2% in the trading industry had vocational/technical certificate while only 0.7% of the entrepreneurs in the trading industry had master’s degree. The Chi-square test suggests that gender, age, duration the entrepreneurs have stayed in South Africa, duration of operating the business and education, and the type of industry that the entrepreneurs were involved were not significantly associated.

Empirical data have revealed that, African immigrant entrepreneurs have employed many of their workers almost the same time as the duration of operating their businesses. To affirm this, the following quotes exemplify this point:

“I have been working here for 5 years now” (P#6).

“I have been working here for 4 years now” (P#8).

“I have been working here for 3 years now” (P#3).

Ownership Form and People Employed

The researchers were interested to establish the form of business African immigrant entrepreneurs were operating and the number of people they employed as indicated in Table 2. Majority (92.8%) of the sole proprietor business form employed between 1 and 5 people and the family businesses employed between 6 and 10 people. Chi-square statistic test (X2 ) of independence of the results in regards to number of employees amongst the three categories of businesses resulted in a probability value of 0.001 hence, it can be concluded that there was a significant difference or notable difference with regards to employment within the three forms of business ownership.

| Table 2: A Cross Tabulation On Form Of Business And The Number Of People Employed | |||||||||

| How many people do you employ in your business | Total | Summary of Chi-square tests | |||||||

| 1-5 | 6-10 | 16-20 | Computed X2 | df | p-value | ||||

| Form of business ownership | Individual | Count | 142 | 3 | 1 | 146 | 53.805 | 4 | 0.000** |

| % of Total | 92.8% | 2.0% | 0.7% | 95.4% | |||||

| Family | Count | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 | ||||

| % of Total | 2.6% | 0.7% | 0.0% | 3.3% | |||||

| Partnership | Count | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||||

| % of Total | 0.0% | 1.3% | 0.0% | 1.3% | |||||

| Total | Count | 146 | 6 | 1 | 153 | ||||

| % of Total | 95.4% | 3.9% | 0.7% | 100.% | |||||

Note: **represents significance at 0.05 error margin.

Source: Computed from survey results 2016.

The Level of Entrepreneurial Skills Transfer

Table 3 shows that, a significant majority of 143 (93.5%) entrepreneurs indicated that their entrepreneurial skills are very highly transmitted to their employees, though the majority of 100 (65.4%) were the male entrepreneurs. While only two males (1.3%) respondents felt that their entrepreneurial skills transfer to the South African nationals was neutral, this view was contrary to the females (0.0%) respondents who believed that their entrepreneurial skills transfer to the locals is neutral.

| Table 3: A Cross Tabulation On Gender And Level Of Entrepreneurial Skills Transfer | |||||||||

| Immigrants entrepreneurial skills transfer to the locals | Total | Summary of Chi-square tests | |||||||

| Very high | High | Neutral | Computed X2 | df | p-value | ||||

| Gender | Male | Count | 100 | 5 | 2 | 107 | 1.070 | 2 | 0.586 |

| % of Total | 65.4% | 3.3% | 1.3% | 69.9% | |||||

| Female | Count | 43 | 3 | 0 | 46 | ||||

| % of Total | 28.1% | 2.0% | 0.0% | 30.1% | |||||

| Total | Count | 143 | 8 | 2 | 153 | ||||

| % of Total | 93.5% | 5.2% | 1.3% | 100.0% | |||||

Source: Computed from survey results 2016

The excerpts below corroborate the quantitative findings and cement the affirmation of entrepreneurial skills transfer from the African immigrant entrepreneurs to their employees. With regard to this sentiment, some interviewees alluded as follows:

“Yes I think so because I now have great insight and knowledge of the business operation” (P#10).

Further, some interviewees supported this sentiment when asked by saying:

“Yes, because I can now cook some of the other African dishes I never even knew their names talk less of knowing how to cook them. Now I can do it very well without my boss’ guidance” (P#4).

Additionally, a group of interviewees when asked said:

“Yes, I came here very empty without knowing anything in terms of car repairs, but today I can service many cars due to what I have learnt from my boss for the time I have spent in this garage. Today I have gained mechanical skills and knowledge from my boss” (P#3).

“I agree with the fact that I have learned a lot of new technological skills from my boss since joined him in this computer repairs shop, I can now repair computers on my own and only asked my boss when it becomes complicated. So I am very happy”.

Chi-square statistic test (X2) of independence of the results in regards to the entrepreneurial skills transfer amongst gender resulted in a probability value of 0.586 hence, it can be concluded that there was no significant difference in the perceptions of skills transfer to the SA nationals among gender. These findings are consistent to a study conducted by Kalitanyi & Visser (2014) who reported that African immigrant entrepreneurs believe and confirm that there is a high level of entrepreneurial skills transmission to South Africans who work for them. At the same time, local employees also confirm that a transfer of entrepreneurial skills is taking place between their immigrant employers and them (Kalitanyi & Visser, 2010b:2014).

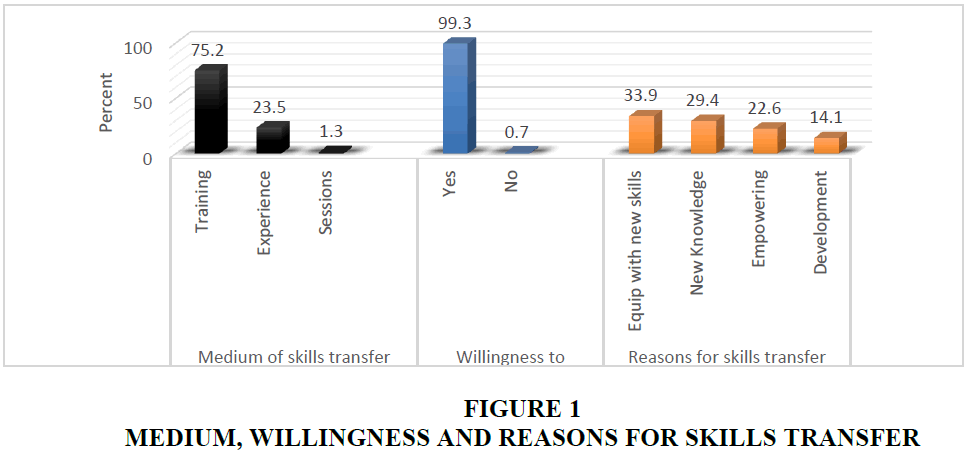

Medium for Entrepreneurial Skills Transfer

To approve the businesses' discoveries, local employees were also interviewed concerning their opinions about entrepreneurial skills transmission. The factors used to affirm the entrepreneurial skills transmission were training, experience and session which inspired innovative action. Consistently, they all concurred that they gained skills relating to starting and running a small business. Figure 1 indicates that, 75.2% (115) 32% of entrepreneurial skills acquisition is done through training. This finding is validated by Kalitanyi & Visser (2014) who reported that 42% of African immigrant entrepreneurs are of the opinion that they transmit their entrepreneurial skills through training and/or teaching. The sentiments below endorse the medium of skills transfer through training as indicated by some participants:

‘‘I have been working here for only 3 years now but I have learnt many skills concerning car repairs and diagnoses through training that I would have taken more time to learn if I was studying them at school. My boss has been a good trainer and instructor, he is a very patient man with his trainees and I am happy to work with him’’ (P#3).

Some interviewees buttressed this by saying:

“My boss give us formal training here. Anytime he is working on something he always tell me/us to be attentive and watch how he does it, open it, the name of the part and how to test and replace the parts” (P#3).

Furthermore, a group of the interviewees said that:

“Through training and experience, I watch my boss prepare similar dishes most often over these years. Sometime, I will ask her the names of the different condiments that she put into the food and the type of dishes. She always tells me/us the names of the different dishes. In this way, I continuously assist in the cooking of the food and then sometimes I will do them alone with her supervision” (P#4).

Meanwhile, a significant number of the interviewees stated that:

“Through training and experience, I have learnt to know the names of products, how to take stock and the different pricing of the different products sold in this shop which I didn’t know at first because I only learned all this about the business after my employment” (P#7).

In support of the aforementioned findings, a considerable lot of them helped their bosses to answer the survey, which affirms their insight into the condition of the business to a decent connection among employee and employer. In line with the objective of the study, to critically analyse how African immigrant entrepreneurial skills are transferred to their employees, particularly the South African, the quote below from some interviewees exemplifies this sentiment:

“When I was employed here my job description was to wash and clean the plates after the customers have finished their meals. But since I have been working here for 3 years with my boss she has taken time to train me on how to cook some of the food that I never knew to prepare nor even know their names before. I really appreciate that and I am hoping to open my own restaurant when I have saved enough capital in the future” (P#3).

Correspondingly, the results (Figure 1) reveals that 36 (23.5%) are of the opinion that experience is the best medium through which skills are being transferred to the SA nationals. In linking this finding with that of Kalitanyi & Visser (2010b:2014), they further reported that 33% of interviewed African immigrant entrepreneurs believe that the acquisition of experience is another way through which they are helping their local employees to become entrepreneurs. Moreover, only two (1.3%) confirmed transmitting skills such as entrepreneurial skills, managerial skills and technical skills through course sessions. This low level of innovative skills securing through session to entrepreneurship is because of the absence of pioneering mindfulness in workers when they join the business. Not long after in the wake of understanding the budgetary advantages of maintaining one's own private venture, they begin moving into business enterprise as the following quotes typify:

“I am a part time student at the University but I work here and also take part time session in computer courses from my employer to gain skills and knowledge on technology and he offer them to me for free, this has helped my computer literate skills” (P#5).

Moreover, one participant from a group of interviewees supports this feeling by saying that:

“Since my working here I have gained much experienced in this business from my employer. With the experience and knowledge that I have acquired in this business I believed that if I accumulate enough capital I will venture in the same line of business in the future” (P#8).

Additionally, other finding concerning skills transmission was that African immigrant entrepreneurs communicated their readiness to impart their innovative abilities to local people. Figure 1 revealed that, a whopping 99.3% of the entrepreneurs showed complete willingness to share their entrepreneurial skills with the South Africans. This finding ties with a study conducted by Kalitanyi & Visser (2010b:2014) who established that African immigrant entrepreneurs expressed their willingness to share their entrepreneurial skills with locals, though some of them posed certain conditions on prospective employees, such as if they are also willing to learn or if they bring capital. The following quotes expand this point:

“Yes, my boss has been teaching me how to conduct this business since I started working with her and she doesn’t take any fee for training me or whatsoever. Besides, she pays me every month as an employee which motivate me very much to be working hard” (P#14).

Another interviewee pointed out when asked that:

“Yes, my boss is very willing to teach me and that is why I joined him. My parents didn’t have money to send me to school so they approach my boss and asked for assistance in teaching me his profession and he accepted. Besides, he also pays me some allowance every month to enable me transport myself to and from work, also to do some of my personal things” (P#1)

The results (Figure 1) above shows that, a notable majority 84 (33.9%) of the respondents agreed of sharing their entrepreneurial skills with SA nationals in order to equip them with new skills, while 73 (29.4%) asserts that sharing their skills with SA nationals gives them new knowledge in the business environment. While 56 (22.6%) agreed that sharing their skills empower the South African nationals to be able to be independent on their own, only 35 (14.1%) believed that sharing their skills with the SA nationals develops them in the business environment. The skills transmission from African immigrant entrepreneurs to employees was also confirmed by the then Deputy Minister of Home Affairs Malusi Gigaba on the occasion of celebrating Human Rights Day, 22 March 2007. He said, “South Africans need to realize that the country can benefit from the presence of immigrants and refugees, because many of them bring skills, including some of the scarce skills needed by the South African economy”. He claimed that the "entrepreneurial spirit and culture" that many refugees bring can, "if properly harnessed" benefit local communities (Benton 2007).

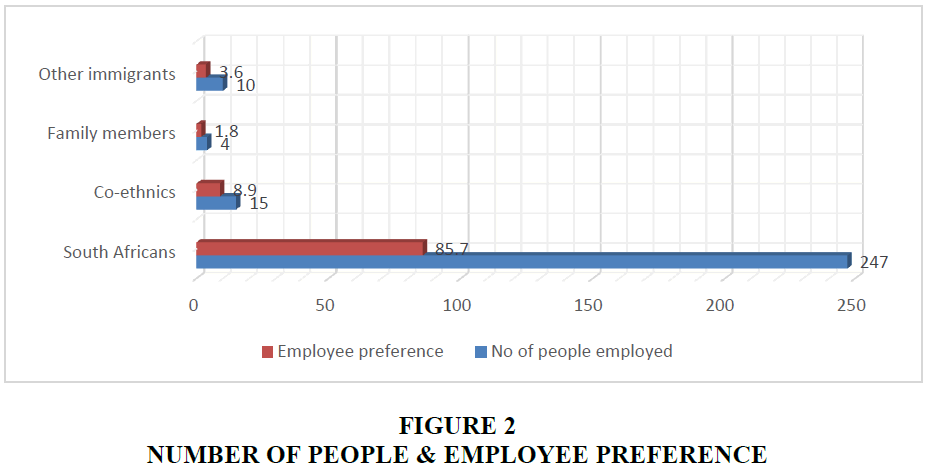

People Employed and Employees’ Preference by Nationality

It was interesting for the researcher to establish the number of people employed and the entrepreneurs’ employment preference by nationality.

Figure 2 shows an overwhelming majority of 144 (85.7%) African immigrant businesses employed locals. These findings are consistent with previous studies (Abor & Quartey, 2010; Fatoki & Patswawairi, 2012) which established that immigrant entrepreneurs employ mostly native South Africans, implying that immigrant entrepreneurship can be one of the ways to address increasing unemployment. Employing locals has also the advantage to the business in that they act as a communication medium while gaining financially and acquire business skills. In response to the above-mentioned literature, it can be seen from on a whole that African immigrants who put their entrepreneurial skills into operation in South African end up employing more citizens than their foreign counterparts signifying a contribution to the host economy.

Results And Discussions

Immigrant entrepreneurship is associated with economic contribution of their host nations. In fact, a number of studies (Fairlie & Lofstrom, 2014; Fairlie, 2008; Ngota et al., 2017) have emphasised self-employment and survival of immigrant entrepreneurs within their host nations. Studies have suggested that immigrant entrepreneurs are more likely to start up a new business that their native counterpart (Fairlie & Lofstrom, 2014), including African immigrant entrepreneurs. With the intention to either becoming self-employed or survive in a host nation, the overall outcome is a new business start-up which eventually create employment opportunities for others, consequently leading to skills transfer. The main objectives of the study were to explore whether African immigrant entrepreneurs transmit their entrepreneurial skills to their employees, the medium through which these skills are transmitted as well as to establish the willingness that these immigrants are ready to share their entrepreneurial skills with their employees in general and South Africans in particular. The study and literature study shows that the study achieved its objectives.

Using a likert scale to measure entrepreneurial skills transfer, it revealed that African immigrant entrepreneurial skills are highly transmitted to their employees in general and South African nationals in particular. The statistical analysis showed that there was no significant difference in the perceptions of skills transfer to employees in general and the nationals in particular. This can be likened to a study by Kalitanyi & Visser (2014) who posit that immigrant entrepreneurial skills are asserts to the South African economy and not a liability.

Studying the means through which African immigrant entrepreneurs transfer their entrepreneurial skills to their employees via training, experience and sessions. The study revealed that African immigrant entrepreneurs transmit their entrepreneurial skills to their employees highly through training as shown by the results from the respondents and the interviews. Also, it showed that skills can as well be transmitted through experience and sessions. In our literature study, we found few studies about African immigrant entrepreneurial skills transfer. However, studies about immigrant entrepreneurial skills transfer require some sort of support (Kalitanyi & Visser, 2010a; Khosa & Kalitanyi, 2015; Ngota et al., 2017) for the immigrant entrepreneurs to keep their business surviving in order to be able to create job opportunities to some individuals, thereby creating an opportunity for skills transfer. While the government request time to put their strategies and policies on immigration and skills development in order, the nation would embrace a short to long-term solution to skills shortage in the country which immigrant entrepreneurship is one of them.

It is considerable from the results that African immigrant entrepreneurs showed much willingness to share their entrepreneurial skills with their employees and the South African nationals in particular. This findings differ with results of previous study by Kalitanyi & Visser (2014) who established that African immigrant entrepreneurs articulated their willingness to share their entrepreneurial skills with locals, but some of them posed certain conditions on prospective employees, such as if they are also willing to learn or if they bring capital. Moreover, these immigrants alluded that their willingness to share their entrepreneurial skills with the locals is to equip them with new skills, new business knowledge, to empower and develop their skills for a business venture in the future.

Further statistical analysis of the data revealed that gender, duration of stay in South Africa, duration of operating businesses in South Africa, education of the entrepreneurs and the type of businesses that the entrepreneurs were involved were not in any way significantly associated. Also, additional statistical analysis showed that there were some notable differences at probability value of 0.001 with regards to the number of people employed amongst the different types of businesses.

Finally, from the overall results, it can be interpreted that African immigrants who arrive in South Africa comes with entrepreneurial skills which they channel towards entrepreneurship. These immigrants create new ventures, employ individuals to assist in their businesses and in the instance transfer their skills to their employees. In a nutshell, these immigrants who come with such entrepreneurial skills could supplement the skills shortage, contribute to job creation and alleviate poverty in South Africa.

Conclusion

This paper aims to contribute to the nascent literature on how African immigrant entrepreneurial skills are being transmitted to their employees in general and SA nationals in particular. The analysis of the data found that African immigrant entrepreneurial skills are being transmitted to their South African nationals’ employees. The respondents in this survey were, on the whole, positive and optimistic in their entrepreneurial impact on skills transmission. In consistent with the survey statistics, the quotes from the African immigrant entrepreneurs employees of which majority were South African nationals confirmed this sentiment. However, immigrants entrepreneurs expressed different ways through which skills was being conveyed ranging from training, experience and session. With the current economic atmosphere that is witnessing high rate of unemployment, the study recommends that the government and the appropriate Departments including the municipalities should include immigrant entrepreneurs in their economic growth policies, given their contribution to job creation, skills transfer and economic growth. This could be made possible through political willingness to have broad-based, coherent and accommodative immigration policies. Furthermore, it is recommended that, African immigrant entrepreneurs should be encouraged by the Department of Small business and enterprises in creating business support platform in which African immigrant entrepreneurs can share their entrepreneurial skills with the South African entrepreneurs to better co-exist.

EndNote

1. Others on nationality included: Kenya, Sierra Leone, Somalia and Zimbabwe.

References

- Aaltonen, S., &amli; Akola, E. (2014). Lack of trust the main obstacle for immigrant entrelireneurshili? httli://www.liyk2.aalto.fi/ncsb2012/aaltonen.lidf

- Abor, J., &amli; Quartey, li. (2010). Issues in SME develoliment in ghana and South Africa. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics, 39(1), 1–19.

- Asoba, S.N., &amli; Tengeh, R.K. (2016). Analysis of start-uli challenges of african immigrant-owned businesses in selected craft markets in calie town. Environmental Economics, 7(2), 97–105.

- Azmat, G. (2010). Targeting fertility and female liarticiliation through income tax. &nbsli;Labour Economics, 17(3), 487–502.

- Benton, S. (2007). Community liraised for embracing refugees on human rights day. BuaNews, 2, 120-135.

- Bogan, V., &nbsli;&amli; Darity, W. (2008). Culture and entrelireneurshili? african american and immigrant self-emliloyment in the United States. Journal of Socio Economics, 37(1), 1999–2019.

- Borjas, G. (1994). The economics of immigration. Journal of Economic Literature, 32(4), 1667–1717.

- Cazes, S., &amli; Verick, S. (2013). liersliective on labour economics for develoliment. New Delhi: ILO.

- Chamuorwa, W., &amli; Mlambo, C. (2014). The unemliloyment imliact of immigration in South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(20), 2–6.

- Chand, M., &nbsli;&amli; Ghorbani, M. (2011). National culture, networks and ethnic entrelireneurshili: A comliarison of the indian and chinese immigrants in the US. International Business Review, 20(2), 593–606.

- Clark, K., &nbsli;&amli; Drinkwater, S. (2000). liushed out or liulled in? self-emliloyment among ethnic minorities in England and Wales. Labour Economics,7(5), 603-628.

- Cornford, I.R. (1996).&nbsli; The defining attributes of ‘skill’ and ‘skilled lierformance’: Some imlilications for training, learning, and lirogram develoliment. &nbsli;Australian and New Zealand Journal of Vocational Education Research 4(2), 1–25.

- Creswell, J.W. (2014). Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods aliliroach. (4th ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Cross, C. 2006. Foreign migration’s imliact: The skills gali? Journal for Health Service Research Centre Review 4(3), 5–7.

- Crush, J, Tawodzera, G, McCordic, C, Ramachandran, S., &amli; Tengeh, R. (2017). Refugee entrelireneurial economies in urban South Africa. Johanessburg.

- Dalhammar, T. (2004). Voices of entrelireneurshili and small business-immigrant enterlirises in Kista. www.divaliortal.org/smash/get/diva2:7559/fulltext01.lidf

- Dorsten, L.E., &amli; Hotchkiss, L. (2005). Research methods and society: Foundation of social inquiry. New Jersey: liearson lirentice Hall.

- Fairlie, R.W. (2008). Estimating the contribution of immigrant business owners to the U.S. economy. Washington, D.C: Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy.

- Fairlie, R.W. (2012). Immigrant entrelireneurs and small business owners and their access to financial caliital. Economic Consulting Santa Cruz, 9(1), 1–46.

- Fairlie, R.W., Zissimolioulos, J., &amli; Krashinsky, H.A. (2010). The international asian business success story: A Comliarison of chinese, indian, and other asian businesses in the United States, Canada, and United Kingdom. In J. Lerner and A. Shoar (eds.), International Differences in Entrelireneurshili. Chicago: University of Chicago liress and National Bureau of Economic Research, 179–208.

- Fairlie, R.W., &amli; Lofstrom, M. (2014). Immigration and entrelireneurshili. In ed. li.W In Chiswick, B.R. and Miller (eds.), Handbook on the Economics of International Migration. Elsevier.

- Fatoki, O., &amli; liatswawairi, T. (2012). The motivations and obstacles to immigrant entrelireneurshili in South Africa. Journal of Social Sciences, 32(2), 133–42.

- Habiyakare, E., Owusu, R. A., Mbare, O., &amli; Landy, F. (2009). Characterising african immigrant entrelireneurshili in Finland. In S. li. Sigué (Ed.), Reliositioning African Business and Develoliment for the 21st Century.” In lieer-Reviewed liroceedings of the 10th Annual International Conference Held at the Slieke Resort &amli; Conference Centre. Kamliala - Uganda: Makerere University Business School.

- Hunt, J., &amli; Gauthier-Loiselle, M. (2010). How much does immigration boost innovation? American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 2(2), 31–56.

- Johnson, R.B., Onwuegbuzie, A.J., &amli; Turner, L.A. (2007). Towards a definition of mixed methods research. &nbsli;Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(2), 112–33.

- Kahn, S, La Mattina, G., MacGarvie, M., &amli; Ginther, D.K. (2013). Hobos’, ‘star’ and immigrant entrelireneurs’.” httli://lieolile.bu.edu/skahn/entrelireneurshili_kahn et al.lidf

- Kalitanyi, V., &amli; Visser, K. (2010a). African immigrants in South Africa: Job jakers or job creators?” South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 13(4), 376–90.

- Kalitanyi, V., &amli; Visser, K. (2010b). Migration and migrant entrelireneurial skills in South Africa: Asserts or liabilities? Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences2, 5(14), 147–58.

- Kalitanyi, V., &amli; Visser, K. (2014). Migration and migrants entrelireneurial skills in South Africa: Assets or Liability? Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(14), 147–59.

- Kerr, W.R., &amli; Lincoln, W.F. (2010). The sulilily side of innovation: H-1B visa reforms and U.S. ethnic invention. Journal of Labor Economics, 28(3), 473–508.

- Khosa, R.M., &amli; Kalitanyi, V. (2014). Challenges in olierating micro-enterlirises by african foreign entrelireneurs in Calie Town, South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences2, 5(10), 205–215.

- Khosa, R.M., &amli; Kalitanyi, V. (2015). Migration reasons, traits and entrelireneurial motivation of african immigrant entrelireneurs. Journal of Enterlirising Communities: lieolile and lilaces in the Global Economy, 9(2), 132–55.

- Leedy, li.D., &amli; Ormrod, J.E. (2010). liractical research: lilanning and design. Ulilier Saddle River, NJ: Merrill lirentice Hall.

- Letseka, M., &amli; Maile, S. (2008). High university droli-out rates: A threat to South Africa’s future. Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC). liretoria.

- Lofstrom, M. (2002). Labor market assimilation and the self-emliloyment decision of immigrant entrelireneurs. Journal of lioliulation Economics, 15(1), 83–114.

- Lofstrom, M. (2017). Immigrant entrelireneurshili: Trends and contributions. Cato Journal 37(3): 503–22.

- Mabadu, R.M. (2014). The role of social networks in the creation and develoliment of business among african immigrants in Madrid Area (Sliain). &nbsli;Journal of Small Business and Entrelireneurshili Develoliment, 2(3), 27–46.

- Ngota, B.L, Rajkaran, S, Balkaran, S., &amli; Mang’unyi, E.E. (2017). Exliloring the african immigrant entrelireneurshili-job creation nexus?: A South African Case Study. International Review of Management and Marketing, 7(3), 143–49.

- Ntema, J. (2016). Informal home-based entrelireneurs in South Africa-How non-South Africans outcomliete South Africans. Africa Insight, 46(2), 44–59.

- O’Neill, R.C., &amli; Viljoen, L. (2001). Suliliort for female entrelireneurs in South Africa: Imlirovement or decline?” Journal of Family Ecology and Consumer Sciences, 29(2001), 37–44.

- Richard, J.C., &amli; Schmidt, R. (2010). Longman dictionary of language teaching and alililied linguistics, (4th ed.) London: Longman (liearson Education).

- Schuetze, H.J., &amli; Antecol, H. (2007). Immigration, entrelireneurshili, and the venture start-uli lirocess. In S. liarker. (ed.), The Life Cycle of Entrelireneurial Ventures: International Handbook Series on Entrelireneurshili. New York: Sliringer.

- Smith, Y., &amli; Watkins, J. (2012). A literature review of sme risk management liractices in South Africa. African Journal of Business Management, 6(21), 6324–30.

- Slieelman, C. (2005). Skill acquisition: History, questions, and theories. In C. Slieelman &amli; K. Kinser (eds.), Beyond the Learning Curve: The Construction of Mind. Oxford: Oxford University liress, 26–64.

- StatsSA, A. (2017). Quarterly labour force survey: Quarterly released. StatsSA. httli://www.statssa.gove.za

- Tengeh, R.K, Ballard, H., &amli; Slabbert, A. (2012). Financing the start-uli and olieration of immigrant-owned businesses: The liath taken by african immigrants in the calie town metroliolitan area of South Africa. African Journal of Business Management, 6(9), 4666–76.

- Vanliatten, B., &amli; Benati, A.G. (2010). Key terms in second language acquisition. New York: Continuum International liublishing Grouli.

- Van de Rheede, T.J. (2012). Graduate unemliloyment in South Africa: Extent, nature and causes. University of the Western Calie.

- Vinogradov, E. (2008). Immigrant entrelireneurshili in Norway. Retrieved from &nbsli;httli://brage.bibsys.no/xmlui/handle/11250/140348

- Volery, T. (2007). Ethnic entrelireneurshili: A Theoretical Framework. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Waldiger, R, Aldrich, H., &amli; Ward, R. (1990). Ethnic entrelireneurs. London: Sage.

- Waldinger, R. (2002). Immigrant enterlirise: A critique and reformation. Theory and society. Newbury liark: Sage.

- Zikmund, W.G, Babin, B.J, Carr, J.C., &amli; Griffin, M. (2010). Business research methods, (8th ed.). Mason, HO: Cengage Learning.