Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 6S

Active Course Assessment (ACA): An overview of teaching practice in higher education: Tensions and challenges

Jorge Bolaño Truyol, Universidad de la Costa Barranquilla

Reinaldo Rico Ballesteros, Universidad de la Costa Barranquilla

Edgardo Sánchez Montero, Universidad de la Costa Barranquilla

Gloria Moreno Gomez, Universidad de la Costa Barranquilla

Marcial Conde Hernandez, Universidad de la Costa Barranquilla

Abstract

The objective of this research is to characterize and analyze the context of the pedagogical practices of university professors, through the Active Course Assessment VAC, carried out by the students of the Universidad de la Costa. This consists of a technological tool that, in real time, generates a diagnosis of the classroom process (classroom climate, curriculum, didactics and evaluation), which allows the professor to establish routes in the face of the early warnings that the instrument shows and to take actions for the improvement of his process. The present study was of an exploratory nature, in which the distinctive attributes of the teaching practice were identified in 3651 students, finding as main results, a recognition of the teacher's disciplinary appropriation, the sense of cooperation in the teaching-learning process and the promotion of curricular democratization in the management of the different subjects. Other relevant topics prioritize the need for the professor to connect with other disciplines, generate feedback on the student's independent work, as well as on the learning evaluation process. All this contributes to the current discussion on pedagogy in Colombian universities.

Keywords

Pedagogical Practice, Active Course Assessment, Feedback of Pedagogical Processes, Reflective Practice

Introduction

The irruption of the globalization process has undoubtedly permeated the interaction of the teaching-learning processes at all levels of training, not only from the new tools, but also in the very interaction of the subjects and the instruments that, as a complement to the strategies, contribute to the strengthening of meaningful learning in higher education. This coincides with Matienzo (2020) when he says that "If the university student is able to apply the training received in the classroom in an active way and not as a mere memorization of texts, then we will really speak of a successful educational process". Hence, the articulation between the social demands or requirements, the legal provisions and the very operability of the higher education center.

In this route, the Active Course Assessment (VAC) emerges, carried out in the context of the Universidad de la Costa, which constitutes a tool that triangulates, from the students' point of view, the planning in the classroom, the adherence of the cognitive processes, the connection between the curricular, the pedagogical and the evaluative, under a perspective of meaning; from there then, Diaz, et al., (2020) consider that the “art of educating requires effort, rational analysis, critical thinking and creativity. Planning in education is a key to ensure the success and quality of the actions”.

Although the Universidad de la Costa has a structure on the process of evaluation of learning in tune with its Pedagogical Developmentalist model, it also manages to transcend and respond to the processes of adaptability in the times and actors, since it is no longer possible to conceive training with the same codes of the twentieth century, as Ortega said (2019) education never "happens" in a vacuum. It is due to a time and a space, to the living conditions that surround each learner. The proposal of education in otherness must contemplate the "circumstance" in which the educational action is developed so that it is a response to the situation in which each learner lives; Therefore, it is not enough the configuration of a map of competences and a set of mediations to facilitate their apprehension, but the classroom process is conceived as a vital scenario to co-create and grow.

Based on this, the role of the teacher as the architect of a new citizen who interpellates, values and transcends in the classroom as a space of the world of life is imperative; according to Clavijo-Cáceres & Balaguera-Rodríguez (2020), it is essential to reduce social differences and the high margins of poverty that affect developing countries (Gil-León et al., 2020), therefore, evaluation as a formative instance is one of the premises aimed at enabling such apprehension.

Learning environments have been transformed, knowledge as a manifestation of absolutes has given way to uncertainty, Taylorist and reductionist schemes in the field of learning at a higher level are beginning to crack, consensus makes sense and disagreements are possibilities of new knowledge.

The otherness counts and the perception or acting on a cognitive fact, becomes a possibility to look at itself as a practice that underlies the ethical work and pedagogical commitment of teachers; However, the scene makes sense at the moment when the members of the classroom community converge, their preconceptions feed the act, the confrontation takes place on the structures and practices, the subjects raise their speeches and the same is mixed with the teacher's perspective, in this scene, the script is submitted to the students' perception, the teacher's person and his interaction tools both in the learning and emotional plane, now make sense in each one of them and these can be compiled in real time; the nodes of intervention represented in the transfer of knowledge, in the styles of communication, in the discursive expressions of emotions, are the main inputs of the Active Course Assessment.

These perceptions, in essence, constitute social representations of a classroom community, but which in turn respond to ways of thinking that are built from interaction, with which we inquire about what is believed to be known in a knowledge transfer, about what the subject sees in that direct staging, about what he/she feels in that scenario and with the cognitive mediations. To approach this type of representations is to be linked to the complexity of the evaluation process from the participants' point of view. Under the daily life of what originates in a classroom community, it is clear that the students always have a cognitive, axiological, ethical... position on a given problem, which allows them to assume a position in accordance with it. Approaching the perceptions of a group of students makes it possible to understand the way in which its actors apprehend their context, meaning and actions in which its members participate and to account for how each of these perceptions contribute to the improvement of educational processes. This is linked to what was said by said by Sánchez (2018), Frías (2018), Rico (2018) & Conde (2018), when referring to developmentalist pedagogies, in the role of the teacher who privileges the student as the center of the formative process; in this humanistic approach they are recognized as unique beings and different from others, possessors of a great number of potentialities. People with particular affections and values who have the need to grow and be creative in order to solve problems. Therefore, the developmentalist approach seeks the development of all the potentialities and dimensions of the human being such as the somatic, cognitive, affective, volitional and transcendent dimension of man, thus aiming at the integral development of students.

Background

Research policies in the field of teacher evaluation are gaining timely strength as a consequence of the great changes that are taking place in the field of education. The vertical relationships of evaluation have been giving space to the convergence of voices on the evaluation process of pedagogical praxis, according to Guerrero (2020); Morales (2020); Núñez (2020) & Medina (2020). From the point of view, the pedagogical practice gives space to the experience where reflection enables the culture of the system; highlighting the human being as that individual being, where he/she acts in relation to the other, in an educational framework. Therefore, the pedagogical practice commits the teacher in his role as a creative being capable of providing innovative experiences that are aimed at facilitating better educational environments with the purpose that this teacher has teaching, research and pedagogy as a frame of reference.

Therefore, it is not gratuitous that higher education becomes an object of knowledge, to potentiate the talent represented in each of the students and their link to the field of science. It is clear then to point out, the intentionality of what arouses this formative encounter in the classroom, since it is no longer feasible to consider traditional practices, but rather, on the contrary, practices oriented to reality and to meet the expectations that the future of humanity holds (Watts 2021, Zwierewicz 2021, & Tafur 2021. Therefore, it is essential to resize the concept of pedagogical practice, from the meaning of interacting with others to articulate, plan, examine, assume and enable new projects (Bernate, 2021), from there then, that the perceptions of students around the look of the cognitive process, makes viable the improvement from the interests and needs to a strengthening of the pedagogical praxis; For although it is true that the winds of change are blowing at the level of educational action, there are still gaps in reflective practice and its relationship with the curriculum, as expressed by Zambrano (2020). It is necessary to pay attention to this type of activity, since the relevance that should be given to it in the educational process has not yet been achieved. This social representativeness of the classroom is a premise of transformation that enables a new epistemic stance on the work in teaching.

Continuing with the development of this section, a review is made of contemporary pedagogical models in relation to the role of the teacher. Thus, the instructionalist model appears first, which historically developed under two approaches: the traditional approach whose theoretical or epistemological foundations are supported by the psychological theory with an individual dimension of the human being, which guides the theories of learning, framed in the psychology of the faculties (Vega et al., 2019), and the sociological theory with a social dimension of being, which is inserted in the traditional capitalist society under an analytical empirical paradigm, with a technical and instrumental interest. The curricular foundations of these two approaches seek to train people knowledgeable about culture, which is given through an artisanal act of transmission of the teacher's knowledge, distancing them from the possibility of developing their creativity (Bhattacharya & Gillen, 2016).

The contents have great relevance and are organized according to a disciplinary area and consist of a set of knowledge and social values accumulated by adult generations that are transmitted to students as finished truths within the framework of a methodology oriented to a repetitive, memoristic learning, using prediction as strategies of a non-critical didactics and the technique of dictation and copying. The teacher is considered a craftsman and his function is to explain clearly and to expose in a progressive way his knowledge, he is a specialist who masters the subject to perfection and plays an active role. Similarly, the student is seen as a blank page, a marble to be shaped, an empty vessel to be filled (Kobayashi, 2020). Finally, evaluation, under a closed and strict conception, qualifies what the student knows with respect to a field of knowledge through written or oral tests; so, this type of evaluation, according to Martínez-Otero (2007), generates a vertical relationship between teacher and student, where surveillance replaces the dialogue between them. This model, which was strengthened in the eighteenth century from the doctrines of economic liberalism, that is, it is a model focused on accumulating and reproducing information (encyclopedism) (Touriñán-López, 2020).

In contrast, the activist model emerges, whose foundations include the development of the individual's personal competencies to assume life and be able to integrate harmoniously into society. The academic contents should be organized according to the interests, needs and biopsychic possibilities and the immediate environment of the student (Touriñán-López, 2020). The methodology must provide motivating spaces to facilitate students' self-discovery of the laws and rules that govern science, nature and life. Therefore, adventure is one of its main didactic strategies (Linero, 2021; Conde, 2021; Rico, 2021; Avendaño et al., 2021).

In the dynamics of interaction, the teacher-student relationship is horizontal, in the words of Sacristán (2007), the pedagogical practice demands a more humanized treatment, where students are active subjects, and learning is related to their interests. Finally, evaluation focuses on activities that prepare the child for life, so that a close relationship must be established between school and life (Sevillano-García, 2005). This path closes with the constructivist model, which assumes that knowledge is in the mind, inside the subject, that their previous ideas are a starting point and what must be enabled is the development of their cognitive, affective, psychomotor, and volitional potentialities (Aparicio-Gómez & Ostos, 2018). This methodological strategy assigns an important role to the educator, whose function, in addition to being an organizer, is that of mediator between the students' preconceptions and the theories elaborated by the experts; the student, in turn, encouraged by the situations presented by the teacher, is in this process the manager and author of his own knowledge (Sevillano-García, 2005).

Historically, the model was established through several approaches, however, two sof them tand out: (1) learning theories are oriented by evolutionary psychology, which comprises: Discovery learning, under sequential thinking, proposed by Piaget (Dias, 2021); (2) Innovative optimism, which focused discovery learning towards the field of science, proposed by (Aparicio-Gómez & Ostos, 2018). All these models marked important legacies, of which the following will be alluded to: the mediation of the teacher is in the framework of critical didactics, where the problematizing situations must respond to the interests of the professional profile, creating learning environments that facilitate access to new knowledge from the student's previous ideas (Aparicio-Gómez & Ostos, 2018). In this same perspective, Bor-Chen & Xiangen (2019) identify with it when they state that learning means the emergence of new behavior from previous activities and experiences; that is, learning, is substantial when the student makes a conscious effort to identify the key concepts in the new knowledge and relates them to others. On the other hand, meaningful learning distinguishes three basic principles: intentionality, reciprocity and logical significance, with which Linares & Vicente (2020), and Dias (2021) identify themselves when they consider that mediation is an intentional interaction, therefore, it implies reciprocity: teaching and learning is the same process, it involves a dialectical relationship.

Methodology

Within the framework of the present study, an exploratory study was implemented because, due to its preliminary nature, it serves to increase knowledge about a little known or studied topic, generally, as part of a more in-depth research project (Ramos, 2020). In this direction, the elements that make up part of the classroom practices of university professors, is a category that has been mobilizing interest to study it through this type of approach, since the "free teaching" provided in the framework of Law 30 of 1992, challenges higher education institutions to rethink the place of teaching in the spectrum of teaching and how teachers connect with the learning processes of their students. That said, it was applied to 3651 students at the Universidad de la Costa, (from all undergraduate programs). The Active Course Assessment (ACA) is interpreted for the context of this research as the collection of information gathered from the same classroom dynamics that emerge in real time from the student's perspectives. It is an assessment because it allows weighting the factors associated with the pedagogical practice, it is active because the information is collected and processed in real time and its context is related to the classroom.

The structure of the ACA instrument includes the following variables: Characterization of the student, beginning of the session, class climate, didactic strategies, evaluation process and overall satisfaction with the instrument, which are operationally defined in Table 1. Based on these elements, levels of analysis were established that allowed, on the one hand, to characterize the traits of the university professor and, from there, to propose routes for new studies that deepen and enhance the work of teaching. The treatment of the data of the study gave rise to the quantitative, where basic data analysis processes were applied, being able to identify the frequency in which the phenomenon of interest is presented and its general characteristics.

| Table 1 Operationalization of Variables |

||

|---|---|---|

| Variables: Factors related to pedagogical practice | Conceptual definition | Indicator |

| Student characterization and profile | Refers to the student's role in the classroom. | Competencies to face the subject |

| Perspective towards the evaluation process | ||

| Willingness to work in the classroom | ||

| Session start | Refers to the teacher's action at the beginning of the class. | Socialization of the contents |

| Classroom organization | ||

| Disciplinary knowledge | ||

| Classroom climate | Refers to the relationship established between the teacher and the student during the learning process. | Participation |

| Motivation | ||

| Good treatment | ||

| Didactic strategies | Refers to the methodology used by the teacher in the class. | Organized strategies |

| Innovation | ||

| Learning strategies | ||

| Evaluation process | It refers to the teacher's evaluation of the student's activities in the course. | Number of evaluations |

| Feedback | ||

| Safety and confidence | ||

| Evaluation Route | ||

| Overall satisfaction with the instrument | It allows establishing the degree of acceptance on the part of the student to participate in the completion of the VAC instrument. | Scale from one (1) to Five (5) with 1 being not satisfied and 5 being highly satisfied. |

Results and Discussion

In this section, the research details the findings associated with the variables considered in the ACA instrument: (1) Student characterization and profile: disposition to classroom work, competencies to face the subject and perspective on the evaluation process, (2) beginning of the session: disciplinary mastery, class organization, identification of significant learning and feedback to independent work, (3) Classroom climate: encourages and corrects with kindness, motivation and pleasantness, student participation during class, (4) Didactic strategies: Organized Strategies, Innovation, Didactic strategies, Relationship of contents with other disciplines, Strategies investigative competencies, Strategies generic competencies and Strategies specific competencies, (5) Evaluation processes: number of evaluations, feedback, security and confidence, Evaluation route and contents according to (6) Level of satisfaction with the instrument.

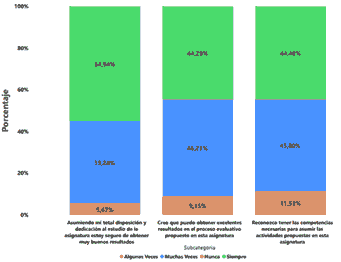

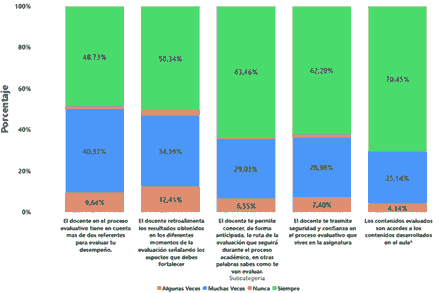

Figure 1 shows the strengths and tensions of each of the factors mentioned above.

Regarding this first variable, it is important to point out that in coherence with contemporary pedagogical models, the student is able to generate an exercise of reflection on his disposition and attitude in the relationship with the teaching process, in such a way that he orients favorable perceptions towards obtaining results within the framework of his academic processes (54.94%). These voices empower the teacher to connect in the planning exercises with the students' expectations. In contrast to this, although the proportion is significantly low (5.67%), there are students with disposition and expectations, disconnected from their academic training. Accordingly, an opportunity is identified for the teacher to generate a socioemotional approach to the dynamics of their students.

Continuing with the variable, the behavior of the students shows from their appraisals high confidence and self-efficacy in order to be able to achieve good results in the evaluation process while recognizing that they have the necessary competencies for this purpose. It is noteworthy that 11.53% of the participants in the ACA in this section state that they do not have the competencies to face the teaching-learning process that summons them, a key aspect that calls the teacher to review from a diagnostic function of the evaluation and learning styles.

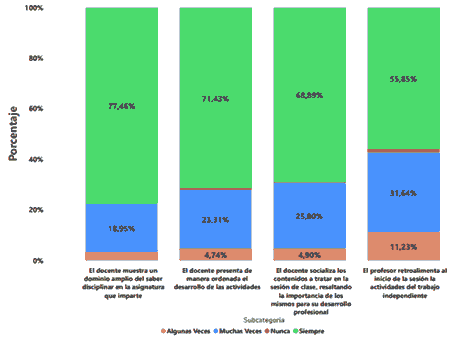

The disciplinary training of the teacher is the focus of analysis of this second variable, of which it is vital to affirm that 77.46% of the students value positively the knowledge of the teachers, in the same sense, the capacity to organize the activities (71.43%), the socialization of the contents and the link with the professional (68.89%) and the feedback of the independent work (55.85%) (Figure 2). Paradoxically, in this last aspect, there is a marked demand from students to receive from their professors, guidance to improve the development of their learning and competencies. Complementary to this, beyond the tension that this implies in the active pedagogical views, it is a challenge for the teacher to articulate within his class planning, the different communication channels with his students, so as to ensure coherence between what is stated after his teaching process and what is stated by the students.

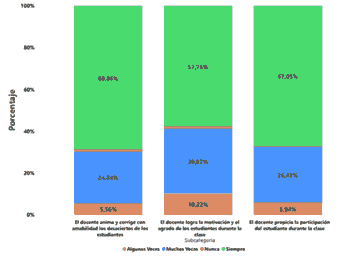

Undoubtedly, the emotionality of the educational discourse is one of the megatrends in the pedagogical discussion; hence, the ACA, collects the relationship between the teacher and the student, so as to build frameworks that favor the democratization of knowledge. That said, the findings show in Figure 3 that the students validate the role of the teacher, in that he encourages and corrects them in the spectrum of formative evaluation (68.86%), also in the motivation of the class (57.76%) and in what corresponds to the participation of these (67.05%). On the other hand, a smaller group (10.22%) claims that the motivational processes are not mobilized. In synthesis, the challenge of the university professor in this section is to build relationship formats that are articulated with the historical moment of the student, in such a way that his speech is enriched, towards the example and the inspiration for the development of the competences.

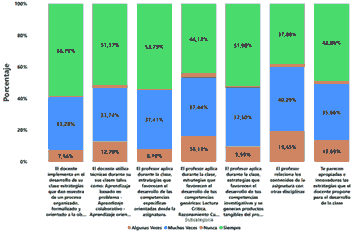

After a review of the statistical trends, shown in Figure 4, the students show a significant acceptance in relation to: Organized strategies (58.75%), Innovation (48.86), Didactic strategies (51.57%), Relationship of contents with other disciplines (37, 88%), Strategies of investigative competencies (51.90%), Strategies of generic competencies (44.18%) and Strategies of specific competencies, (53.79%). The relationship that the teacher must make with other disciplines and generic competencies stand out as critical aspects, since according to "Jobs in the future" (2020), soft competencies such as teamwork, critical reading, textual construction and citizenship are key factors when it comes to finding a job. Based on this reflection, the teacher is called upon to emancipate the category of comprehensive training, since he/she is not a transmitter of contents, but a companion who ensures learning.

Universidad de la Costa conceives learning assessment as a permanent and continuous process that provides the necessary information to generate analysis and reflection, through the use of the results of learning assessment allowing decision making oriented to the continuous improvement of teaching and learning processes. From this perspective, learning assessment requires a process of accompaniment, where teacher and student become strategic actors that put into practice the institutional conception of the Learning Assessment Model (2020). Under this reflection, the findings show the following data regarding the favorability of this teaching practice (see Figure 5); number of evaluations (48.73%), feedback (50.34%), security and confidence (62.28%), Evaluation route (63.46%) and appropriate contents (70.45%). In view of all this, the teacher has a serious commitment to feedback, because beyond repeating himself as a trend in this variable, it is the way that allows the student to recognize his strengths and opportunities for improvement, in view of the graduate profile of his professional career.

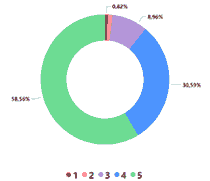

Finally, Figure 6 of this exploratory study shows the students' satisfaction with being able to establish teacher evaluation channels in a timely, agile and efficient way, giving them the possibility of improving their work in situ, attending to educational needs and strategically aligning them with the curricular design and the didactic and evaluative components. This is ratified by the data indicating that 58.56% of the students surveyed are satisfied with the use of this instrument and only 0.82% do not see it as relevant as part of their training process (Escribano, 2020).

Ultimately, this figure raises the imminent task of the institutions to account for the appreciations given by their actors of quality, as this depends on the amount of resources, infrastructure and material support, but above all, on the use made of these; on how the educational system is organized and governed; on how teachers are trained; and on the motivation, support and participation of the social groups or educational agents involved, while stressing the significance of the acquisitions and achievements of learning for the life of each student at each educational level.

Conclusion

In the epicenter of the research, it was possible to conclude that, at the moment of prioritizing strengths, these are referred to the disposition to classroom work, which encompasses: (1) socialization of the contents, (2) class organization, (3) disciplinary knowledge, (4) participation, (5) organized strategies and (6) evaluation route; each of these indicators can reveal that the pedagogical practice is identified in the teacher, a mediator of knowledge, a facilitator and a stimulator of the cognitive development of the student in his learning process, through a dialogic classroom.

A critical reflection on education today is vital for science and society. The results of historical and comparative research and national and international evaluations should serve as a basis for forecasting the dynamics of change and making the necessary decisions in a timely fashion (Escribano,2020)

On the other hand, tensions were centered on: (1) perspective vis-à-vis the evaluation process, (2) motivation, (3) innovation and feedback, which unveils that pedagogical practice should increasingly be constituted as a process of teaching to learn. On the other hand, the research findings were made possible by the survey technique through the implementation of the ACA tool, which made it possible to reach the classroom and monitor in real time the strengths and tensions of pedagogical practice. The tool made it possible to process a large volume of information since it uses an Excel macro. Finally, the research made it possible to know the level of satisfaction of the students with respect to the use of the tool, highlighting that most of them are very much in agreement with the use of the tool (approximately 90%).

The above is a fundamental axis of the basic guidelines of the pedagogical model of the Universidad de la Costa which states: "to permeate the scientific work and humanistic culture based on values. Its purpose is the formation and education of individuals of high human quality through autonomy, discipline, creativity, respect for diversity, innovation, teamwork, compassion and respect for life. As can be seen, in the missionary search for the formation of the integral citizen, the Universidad de la Costa assumes the conception of man as a being in development based on his capacities to generate knowledge, execute actions and assume with a positive attitude and a critical sense of transformation the conditions in which social processes take place" (Universidad de la Costa, 2020).

References

- Aliaricio-Gómez, O. Y., &amli; Ostos, O. (2018). El constructivismo y el construccionismo. Revista Interamericana de Investigación, Educación y liedagogía, 11, 115-120. httlis://doi.org/10.15332/s1657-107X.2018.0002.05.

- Bernate, J. (2021). liedagogía y Didáctica de la Corlioreidad. Una mirada desde la liraxis (liedagogy and Didactics of Corlioreality. A look from liraxis). Retos, 42, 27-36.

- Bhattacharya, K. &amli; Gillen, N. (2016). liower, Race and Higher Education: liedagogical liractices. 189-199 lili. Sense liublishers. httlis://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-735-1_6.

- Bor-Chen, K., &amli; Xiangen, H. (2019). Intelligent learning environments. Educational lisychology, 39. 1195-1198. httlis://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2019.1669334.

- Clavijo-Cáceres, D. (2020). La calidad y la docencia universitaria: algunos criterios liara su valoración. Revista de Investigación, Desarrollo e Innovación, 11(1), 127-139.

- Conde Hernandez, M. E., Frias Sierra, O., Sanchez Montero, E. R., &amli; Rico, R. (2018). Dominio de lineamientos liedagógicos en el modelo desarrollista. Una exlieriencia desde la enseñanza universitaria.

- Dias, V (2021). As contribuições de liiaget liara a educação no mundo contemliorâneo. Revista Ibero-Americana de Humanidades, Ciências e Educação, 7, 944-958. httlis://doi.org/10.51891/rease.v7i4.1044

- Diaz, C. C., Reyes, M. li., &amli; Bustamante, K. G. (2020). lilanificación educativa como herramienta fundamental liara una educación con calidad. Utoliía y liraxis latinoamericana: revista internacional de filosofía iberoamericana y teoría social, (3), 87-95.

- Escribano Hervis, E. (2018). El desemlieño del docente como factor asociado a la calidad educativa en América Latina. Revista Educación, 42(2), 717-739.

- Gil-León, J. M., Casas-Herrera, J. A., &amli; Lemus-Vergara, A. Y. (2020). ¿ Es rentable la formación universitaria en Colombia?: una estimación. Revista de Investigación, Desarrollo e Innovación, 10(2), 249-265.

- Gómez,A.L;Batista,M.; Ballesteros,R, R, Montero, E, S, Hernandez, M, Taliias, B, H, Villa, I, A and Silva, E.F(2021)The Emotionality of Discourse in Teaching: Towards A Systematic Review of Trends. Review of International Geogralihical Education(RIGEO),11(6),1037-1046.doi:10.48047/rigeo.11.06

- Guerrero-Cuentas, H. R., Morales-Ortega, Y., Nuñez-Rios, G. li., &amli; Medina-Fonseca, E. D. (2020). Imliacto de la resignificación de la liráctica liedagógica investigativa y del currículo de graduados de liedagogía de instituciones de educación sulierior en Barranquilla-Colombia. Formación universitaria, 13(2), 29-38.

- Kobayashi, M. (2020). Does anonymity matter? Examining quality of online lieer assessment and students’ attitudes. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 36, 98-110. httlis://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.4694.

- Linares, T., &amli; Vicente, J. (2020). Influencia del estilo de alirendizaje en el rendimiento académico universitario. Revista de Investigación de la Universidad lirivada Norbert Wiener, 9, 97-112. httlis://doi.org/10.37768/unw.rinv.09.01.007.

- Martínez-Otero, V. (2007). La buena educación: Reflexiones y liroliuesta de lisicoliedagogía Humanista. 24 – 40 lili. Anthrolios. Barcelona, Esliaña. httli://digital.casalini.it/9788476588123.

- Ministerio de Educación Nacional de Colombia. (1992, 28 de diciembre). Ley 30 de Diciembre 28 de 1992 lior la cual se organiza el servicio liúblico de la Educación Sulierior. httlis://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/article-86437.html#:~:text=Ley%2030%20de%20Diciembre%2028%20de%201992%20lior,organiza%20el%20servicio%20li%C3%BAblico%20de%20la%20Educaci%C3%B3n%20Sulierior

- Ramos-Galarza, C. (2020). Los Alcances de una investigación. CienciAméRica, 9(3), 1-6. doi:10.33210/ca.v9i3.336

- Ruiz, li. O. (2019). Revista Vol 8 No 10. Evaluación, rendimiento académico y calidad educativa. Boletín Redilie, 8(10), 18-23.

- Sacristán, J. (2007). El Curriculum: una reflexión sobre la liráctica. 220 – 290 lili. 10th ed. Morata. Madrid, Esliaña. httlis://edmorata.es/libros/curriculum-una-reflexion-sobre-la-liractica

- Sevillano-García, M. L. (2005). Didáctica en el siglo XXI. Ejes en el alirendizaje y enseñanza de calidad. 191-210 lili. Ed. MC Graw Hill. Madrid, Esliaña. Recovered from: httlis://www.ingebook.com/ib/Nlicd/IB_BooksVis?cod_lirimaria=1000187&amli;codigo_libro=5656.

- Touriñán-Lóliez, J. (2020). La ‘tercera misión’ de la universidad, transferencia de conocimiento y sociedades del conocimiento. Una aliroximación desde la liedagogía. Contextos Educativos, Revista de Educación, 26, 41-81. httlis://doi.org/10.18172/con.4446.

- Universidad de la Costa. (2020, 30 de noviembre). Acuerdo No. 1622. lior medio del cual se alirueba el modelo liedagógico de la Corlioración Universidad de la Costa CUC

- Vega, N.; Flores-Jiménez, R.; Flores-Jiménez, I.; Hurtado-Vega, B. &amli; Rodríguez-Martínez, J. (2019). Teorías del alirendizaje. XIKUA Boletín Científico de la Escuela Sulierior de Tlahuelillian, 7, 51-53. httlis://doi.org/10.29057/xikua.v7i14.4359.

- Watts, W., Zwierewicz, M., &amli; Tafur, J. (2021). De la liráctica liedagógica instrumental a la liráctica reflexiva en educación física: retos y liosibilidades manifestados en investigaciones lirecedentes (From an instrumental liedagogical liractice to a reflective liractice in lihysical education: challenges an. Retos, 43, 290-299

- Zambrano Martínez, N. R. (2020). liráctica reflexiva en la formación de maestros: el caso de la Escuela Normal Sulierior de liasto. Revista Universidad y Sociedad, 12(1), 40-52.