Research Article: 2022 Vol: 25 Issue: 5S

A Systematic Review of the Technology Enabled Child Sexual Abuse (OCSA) & its Impacts

Sana Ali, Allama Iqbal Open University

Saadia Anwar Pasha, Allama Iqbal Open University

Citation Information: Ali, S., & Paash, A.S. (2021). A systematic review of the technology enabled child sexual abuse (OCSA) & it’s impacts. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 25(S5), 1-18.

Abstract

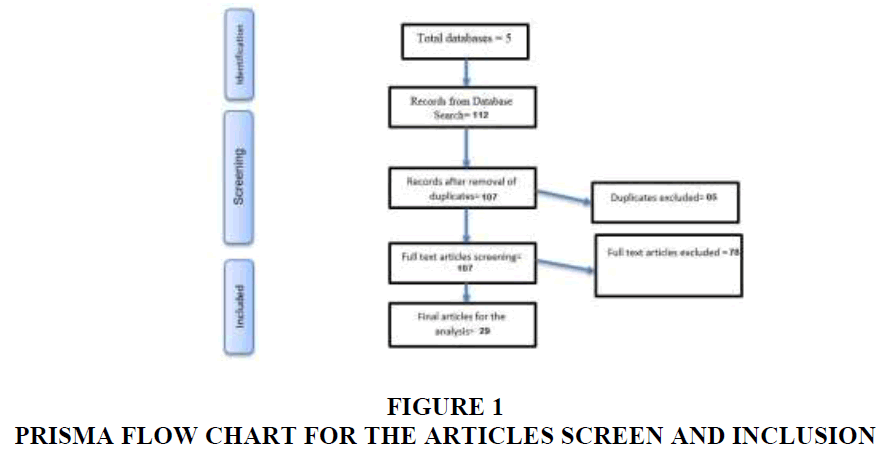

Internet technology accompanying ease of access and ease of use is a significant concern that facilitates sexual violence against children. Consequently, crimes against children are organized, complex, and cannot be identified in many cases. Thus, we also aimed to discuss and highlight Online Child Sexual Abuse (OCSA) and its impacts globally since it is a briskly growing yet under discussion phenomenon. We used the Systematic Review Approach for the current article to extensively examine Child Sexual Abuse in Cyberspace and its potential impacts. We randomly select n=5 major online research databases, including GoogleScholar, ScienceDirect, PubMed, DOAJ, and APA PsycNet, to gather the relevant articles. Further, we executed PRISMA flowchart method for the article selection purposes. After screening the article under inclusion/exclusion criteria, we shortlisted n=29 most relevant articles. Cited literature indicated that the internet is a powerful platform for producing and sharing child sexual abuse-based material that can work instantaneously and anonymously accessible for individuals with deviant sexual interests. As a result, online sexual abuse causes suicides, hostility, panic attacks, depression, disgust, shame, and others among the victims. Sometimes, these impacts are at their peak when parents do not support victims, leading to self-harming behaviour. Thus, an increased number of sexual crimes against children questions children security and rights preservation in Cyberspace. Although such studies are conducted, we need more literature to highlight the causes, types, and impacts of Online Child Sexual Abuse to ensure a better future for the young generation.

Keywords

Child Sexual Abuse, Psychological Disorders, Sextortion, Pornography, Self- Harming Behaviour.

Introduction

Article 19 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child proposes that state parties are obligated to take all administrative, educational, legislative and social measures to ensure children's protection from every type of violence, exploitation, deprivation from fundamental rights maltreatment. At the same time, the minors are in the care of parents or guardians (s) (MacPherson, 1989). However, today, violence against children is a critical social issue all over the world. It is mainly characterized as a public health concern considering the impact on both collective and individual health. A report represented by United Nations Children’s Fund indicated that over 120 million young children face violence, especially sexual violence every year (Brasil et al., 2017). The intensity of sexual violence can be determined by the fact that, in 1999, more than 286,000 faced sexual abuse along with intercourse, and 3600 faced other different types of sexual violence. Similarly, 89% of female victims were 12 to 17 years old, and more than 56% of them faced violent asexual crimes (Ali et al., 2021). Yet, many times the cases of child sexual abuse also remained unreported due to several social factors. Significantly, most cases of acquaintance sexual abuse remain hidden, and even, sometimes, parents are also unaware of the ongoing sexual violence against children (Townsend & Rheingold, 2013). As a result, exposure to sexual abuse during childhood leads to severe mental consequences and physical health problems. These consequences remain persistent into adulthood, such as psychological distress, physical injuries, and long-term chronic diseases such as Human Immunodeficiency Virus (Ward et al., 2018). According to (Sumner et al., 2015), existing research also witnesses exposure to sexual violence causes a broad range of psychological and physical consequences. Depression, anxiety, unwanted pregnancy, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and death of the children in severe cases.

Nevertheless, this vulnerability to sexual violence is questionable both in developed and developing regions. Despite many efforts, child protection laws and strategies remain less influential in overcoming sexual violence against children (Ward et al., 2018). As noted by (UNICEF, 2020), child sexual abuse is a growing social problem that adversely affects the quality of life of many children in the United States and other countries. The more children face sexual abuse, the more they find it difficult to cope with the challenges. Under these circumstances, the optimal development of children and their future remains uncertain as the nature of sexual violence adversely affects their physical and psychological development.

Moreover, technological development accompanying ease of access and ease of use regarding internet technology is another primary concern that has altered sexual violence against children. The extensive availability of web camera peers to peer file sharing facilities has created a clear distinction between Child Sexual Abuse and Online Child Sexual Abuse (Baines, 2008). As a result, child abuse content can be generated online and shared on different platforms to serve the various causes such as commercialization of the relevant content to earn easy money and gratify the deviant sexual interest of the online predators (Baines, 2008). As noted by (Ali, 2019), earlier crimes against children were limited and identifiable. Today, these sexual offences are organized, complex, and cannot be identified in many cases. For example, the statistical reports from the Government of the United Kingdom revealed more than 80,000 suspicious activities in Cyberspace against children. And similar reports from the National Crime Agency in the United Kingdom also identified 2.88 globally registered online accounts on Dark-websites, with at least 6% believed to be registered from the UK. This prevalent Online Child Sexual Abuse can be of many forms, such as involving a child in sexual chat, creating objectionable content, on-camera abuse of the children, sexual solicitation, sharing abusive material, blackmailing the minor, and others (Joleby et al., 2020). Another report prepared by (Thorn, 2019) indicated 480,769 images are uploaded every week based on child abuse based material, mostly pornography. Similarly, more than 78% of pornographic images contain children below twelve years old. The data also showed that 19.58% of material involved boys, and 80.42% involved female children. In 2013, data from the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children showed that approximately 18.0% of online child sexual abuse based content was created by parents/guardians. Neighbours or some other family member produced 25% of the relevant content, and 18% of content was produced through online interaction and enticement (strangers) (Thorn, 2019).

Additionally, the idea about psychological and social consequences of child sexual abuse in general and Online Child Sexual Abuse, in particular, has long been established (Maniglo, 2009). Yet, the impacts of online abuse are still understudied and demanding in-depth approaches. Many areas explore the impacts and link them directly or indirectly to Online Child Sexual Abuse, indicating an explicit literature gap. Depression, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, and others are some common impacts of Online Child Sexual Abuse that are still under study (Joleby et al., 2021).

Thus, by keeping in view the role of Online platforms in facilitating child sexual abuse (Ali et al., 2021), we also conducted this study. Using the systematic review method, we carefully examined the gathered articles to validate the link between the internet and child sexual abuse. Besides, we also discussed its impacts in the light of existing literature which is still under study, indicating several physical and psychological effects of Online Sexual Abuse. We address the following prominent questions:

1. What are some prominent types of online child sexual abuse?

2. What are the Psychological Consequences of Online CSA?

In the first part of the current article, we describe Child Sexual Abuse in general and Online Child Sexual Abuse as an increased social concern. In the second section, we discussed the methodological method to ensure further the transparency and accuracy of data gathering for the current article. In the third section, we extensively cited the gathered literature and discussed the studies accordingly. The fourth section consists of a discussion based on the literature that further helped us draw the conclusions and make recommendations accordingly.

Methodology

We gathered research studies published from January 2000 to June 2021 by searching for the literature on specialized platforms such as Google Scholar, PubMed, Science Direct, Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), and APA PsycNet. However, there was no language restriction. We included studies witnessing child sexual abuse on children of all three gender (male, female, transgender) with the keywords, i.e., Online Child Sexual Abuse, Sextortion in the Cyberspace, Online sexual crimes against children. Impacts of online child abuse, long-term impacts, short-term impacts, emotional consequences, psychological impacts, cybercrimes against children, online Grooming, and online child pornography. Later, we tabulated the data using Microsoft Excel, which further helped calculate the frequency and percentage of the gathered, excluded, and included articles. It is also worth noting that we adopted PRISMA guidelines regarding Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis for review and selection purposes, as suggested by (Biswas et al., 2020). Table 1 indicates the inclusion/exclusion criteria and PRISMA method for the articles inclusions purposes:

| Table 1 Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria | |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

| Studies witnessing impacts of online child sexual abuse | Studies witness impacts of non-virtual child sexual abuse |

| Journals that are indexed in the selected database | Journals that are not indexed in the selected database |

| Articles published in the indexed journals | Articles published in predatory or unregistered journals |

| Reports witnessing impacts of online child sexual abuse | Reports witnessing the effects of online abuse in general |

According to the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1), we randomly selected a sample of n=112 relevant studies from the five selected databases. After the initial scrutiny, we removed n=5 articles as duplicates. After excluding duplicate records, we further examined the n=107 articles and removed n=78 articles as not fulfilling the inclusion criteria of the current research. Eventually, we finalized n=29 pertinent research records for review purposes.

Articles from the Selected Database

After finalizing the n=29 research articles, we made calculations based on their database resources. Table 2 indicates that a majority of 51.7% of articles were from Google Scholar, 31.0% were from ScienceDirect, 10.3% were from PubMed, 3.4% of articles were from the Directory of Open Access Journals, and a similar number of articles (3.4%) were from the APA PsycNet.

| Table 2 Frequency of Finalized Articles from the Designated Database | ||

| Database | N | % |

| Google Scholar | 15 | 51.7% |

| PubMed | 03 | 10.3% |

| Science Direct | 09 | 31.0% |

| DOAJ | 01 | 3.4% |

| APA PsycNet | 01 | 3.4% |

| Total | 29 | 100% |

Articles by Year, Method, Design, Paradigm Models & Collection Techniques

We further calculated the finalized articles according to their year of publication, design, method, and paradigm models.

As summarized in Table 3, most articles (58.6%) were published from 2016 to 2021, 17.2% were published from 2006 to 2010, 17.2% were published from 2011 to 2015, and 6.6% of research articles were published between 2000-2005.

| Table 3 Frequency of the Articles by Year, Study Design, Paradigm Models & Data Collection Methods | |||

| Variables | Constructs | N | % |

| Study Year | 2000-2005 | 02 | 6.8% |

| 2006-2010 | 05 | 17.2% | |

| 2011-2015 | 05 | 17.2% | |

| 2016-2021 | 17 | 58.6% | |

| Study Design | Case study | 07 | 24.1% |

| Cross-sectional | 08 | 27.5% | |

| Longitudinal | 01 | 3.4% | |

| Other | 13 | 44.8% | |

| Parading Model | Quantitative | 21 | 72.4% |

| Qualitative | 08 | 27.6% | |

| Mix-method | 00 | 0.0% | |

| Data Collection Method | Survey | 06 | 20.6% |

| Literature Review | 11 | 37.9 | |

| Interview | 05 | 17.2% | |

| Content Analysis/Documents | 05 | 17.2% | |

| Other | 02 | 6.8% | |

Besides, we found that 44.8% of gathered studies were from the other types, such as review articles, research essays, reports, and perspectives. However, 27.5% of articles were based on a cross-sectional design, 24.1% were case studies, and 3.4% were based on longitudinal study design. According to the paradigm models of the selected literature, 72.4% of articles were quantitative, 27.6% were qualitative, and 0% of records were categorized as "others" Finally, we have 37.9% of articles as literature reviews, 17.2% are based on qualitative interviews, 17.2% had content analysis, and 6.8% were based on the other methods.

Primary Themes

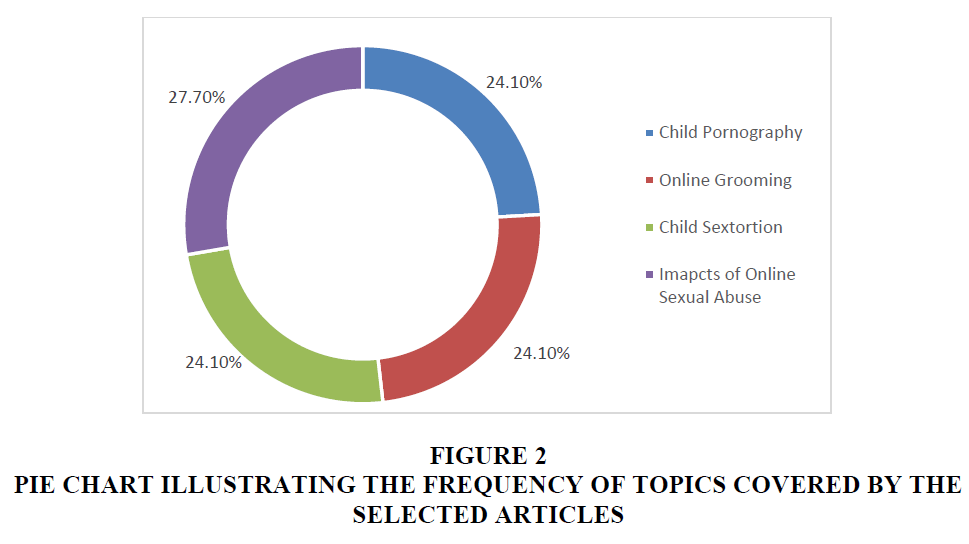

To ensure transparency in selecting and adding the relevant literature, we also calculated the frequency of articles according to their relevant topics. (Figure 2) below graphically illustrates the topics covered by the selected literature. Thus, we found that 24.1% of articles addressed online Sextortion, 24.1% of articles discussed online child pornography, and a similar number of articles also addressed child Sextortion (24.1%). Besides, 27.7% of articles highlighted and discussed the impacts of online child sexual abuse.

Online Pornography

According to Burke et al. (2002), a rapid increase in indecent images of children for sexual gratification purposes is a growing concern. Today, law enforcement agencies, clinicians, psychologists, and other stakeholders need to familiarise themselves with the meaning, interpretation, and hazards of producing and possessing child pornography on both the victim and the offender. Notably, child sexual abuse through misusing the internet is a complex issue. It demands the right action from the law enforcement agencies, but it also emphasizes the whole society to stand against it. The contemporary offence-process and etiological theories also witness a strong relationship between the internet and child pornography. Recent studies highlight that possessing child pornography is directly associated with a deviant sexual interest in children as a primary mechanism behind intimacy towards minors. Table 4 Consequently, possessing and utilizing child pornography even leads to violent sexual crimes against children as well (Elliott & Beech, 2009).

| Table 4 Summary of the Literature Regarding Online Child Pornography | |||||

| Source | Design/Method | Journal/Publisher | DOI/ISBN | Aim | |

| (Burke et al., 2002) | Review Article | Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law | 10.1375/pplt.2002.9.1.79 | To examine what child pornography is? What are the treatment and characteristics of offenders? | |

| (Krone, 2004) | Review Article | Trends & Issues in crime and criminal justice | 0642538433 | Examining the child pornography on the internet |

|

| (Elliott & Beech, 2009) | Review Article | Aggression and Violent Behavior | 10.1016/j.avb.2009.03.002 | What is child pornography in Cyberspace? | |

| (Amos, 2009) | Review Article | Scientific World Journal | 10.1100/tsw.2009.147 | To examine accidental exposure to child pornography | |

| (Seto et al., 2010) | Qualitative method | Journal of Sexual Aggression | 10.1080/13552600903572396 | To examine the patterns of child pornography in an online environment | |

| (Merdian et al., 2013) | Review Article | Journal of Sexual Aggression | 10.1080/13552600.2011.611898 | What is child pornography, child pornography on the internet and its narratives by the offenders | |

| (Rimer, 2019) | In-depth ethnography research | Child abuse and neglect | 10.1016/J.CHIABU.2018.12.008 | The perceived difference between online and offline child pornography | |

Sometimes, while using and searching a desired content on the internet, child pornographybased material also popups up as advertisements and scam emails. Although cybercrime wings worldwide are trying to hamper child pornographic advertisements and emails, their prevalence’s are a thought-provoking phenomenon (Amos, 2009). This deliberate role of the internet in accidental exposure to child pornography is also affirmed by (Seto et al., 2010) as they conducted qualitative interviews of the offenders convicted for the possession of child pornography in Canada. Data gathered from the two distinct samples of offenders revealed that most respondents showed a deliberate effort to access child pornography, but some of the respondents denied it. However, a prominent number of individuals revealed an accidental exposure to child pornography on the internet, which further raised severe questions on the internet-based advertisements and scam emails. Moreover, findings also indicated a comparatively more extreme sexual interest in child pornography and sexual violence against minors. The severity of online child pornography can be determined by the fact that it is not only based on videos or photos. Also, audio or written content that causes sexual arousal towards minors is pornography. Today, online child pornography is one of the most heinous crimes that have 491% increased since the millennium indicating either paedophilia or growing deviant sexual interest towards children (Merdian et al., 2013). Further, Merdian et al. (2013) also divided Child Pornography Offending into three primary dimensions:

1. Fantasy driven and contract-driven, where an offender deliberately collects child pornographic content through online abuse of the child or accessing the platforms where the relevant material is available.

2. Motivational factors behind collecting Online Child Pornographic content can be either preferential or situations. In a situational context, an offender deliberately searches for pornographic content to gratify their deviant sexual needs or trading purposes to earn easy money. In the preferential context, an offender looks consciously and repeatedly for the child's pornographic material. Individuals with motivational factors are generally categorized as either having a paedophilic interest in minors or a general interest in deviant sexual gratifications. Also, these individuals have long-term, extremely deviant, fantasy-driven sexual urges towards children that further lead to develop even more tactful offending methods (Merdian et al., 2013). Thus, these motivational dimensions are based on four "Motivational Types" i.e., Pedophilia, Financial factors (trading), Deviant Sexual Interest, or Curiosity.

3. The third and final dimension involves “The Social Component of Child Pornography" where an increased Child Pornography collection behavior is directly associated with increased social contact and involvement with the other offenders, which leads to curiosity or urge concerning Child Pornography (Merdian et al., 2013). Besides, an increased interest in online child pornography can be attributed to what (Rimer, 2019) found in in-depth ethnographical research. She investigated the perceptions of online child pornography offenders in the United Kingdom. Results gathered from inductive analysis, observational method, and semi-structured interviews revealed the offenders’ deviant perceptions about offline child sexual abuse and online child pornography. According to the respondents, offline child sexual exploitation is irrational, unethical and needs to strengthen the child protection laws. However, the participants responded differently about online child pornography. According to them, online child pornography is harmful, secretive, unreal, and less-sexualized, stipulate the perceived difference between “real” and “unreal” child sexual abuse as highly problematic.

Online Grooming

A brisk advancement in Information Technology has provided us with an unparalleled opportunity to conduct an efficient and real-time communication. Regardless of the time and geographical differences, people can interact with each other. Consequently, communication technology has also enabled online child sex offenders to access vulnerable children online and groom them for sexual gratifications (Choo, 2009). It is notable that, this virtual or non-virtual, both faces to face predation are known as "Grooming" which is aimed at specific goals such as secrecy, compliance, and eventually gaining access to the victim. For grooming purposes, an offender uses flattery to compel the victim into sexual activity and then uses even more heinous strategies to ensure that the victim remains obligated and keeps their relationship a secret (Black et al., 2015).

A report represented by the Australian Institute of Criminology indicated some critical ways in which Innovation Technology has facilitated child sexual grooming (Table 5). These critical ways mainly involve:

| Table 5 Summary of the Literature Regarding Online Grooming | ||||

| Source | Design/Method | Journal/Publisher | DOI/ISBN | Aim |

| (Choo, 2009) | Book | Australian Institute of Criminology | 228436 | Examining the online Grooming of minors for sexual abuse |

| (Aiello & McFarland, 2014) | Case study | Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) | 10.1007/978-3-319-13734-6 | To examine the automatic classification of online grooming stages. |

| (Black et al., 2015) | Content analysis, cross-sectional design | Child Abuse & Neglect | 10.1016/J.CHIABU.2014.12.004 | Understanding online grooming in the Cyberspace |

| (Villacampa & Gómez, 2016) | Case study | International Review of Victimology | 10.1177/0269758016682585 | Analyzing the patterns of online Grooming |

| (De-Santisteban et al., 2018) | Qualitative analysis | Child Abuse & Neglect | 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.026 | Understanding online grooming against children |

| (Gunawan et al., 2018) | Case study | Telkomnika (Telecommunication Computing Electronics and Control) | 10.12928/TELKOMNIKA.v16i3.6745 | To examine the online grooming-based conversation. |

| (Ranney, 2021) | Process-oriented approach, Review study | Child and Adolescent Online Risk Exposure | 10.1016/B978-0-12-817499-9.00003-X | To examine the process of online child grooming for sexual exploitation. |

1. Using anonymized web protocols, password authentication, encryption methods, and steganographic methods.

2. Trafficking child pornography through encrypted online platforms.

3. Using different search engines to access susceptible children.

4. Virtually molesting the children even through video games or on-camera abuse.

5. Gathering personal information of the child and groom them for an offline sexual abuse (Choo, 2009). Mainly, online Grooming is premeditated and organized conduct that first involves possible efforts to win a minor’s trust, primarily known as "Deceptive Trust Development." This first stage consists of exchanging personal information, including age, name, gender, as the predator builds up common grounds with the victim. In the second stage, the predator triggers the child’s sexual curiosity as the predator directly entraps and grooms the child for sexual activity. Gradually, the victims isolate themselves from their family, friends which is an organized part of the entrapment cycle, resulting in a robust victim-offender trust relationship. Finally, in the third stage, the offender persuades the child for a “Physical Approach” and asks personal questions, for example, the minor's location, residence, and parents’ schedule (Aiello & McFarland, 2014).

A study conducted by (Villacampa & Gomez, 2016) further investigated the children's online communicative patterns, making them more vulnerable to potential predators in Catalonia, Spain. The quantitative data gathered from n=489 secondary school level children indicated that most respondents do not prefer accessing the unknown individuals as they are well aware of the "stranger danger". However, predators themselves approach them for interaction purposes. These results highlight the role of children in avoiding any sexual grooming, yet it also indicates online predators as consistently searching for vulnerable children. These results also revealed that online predators accessed almost one out of every twenty children to talk about sex.

Similarly, one out of every ten children also confronted the strangers stressing to talk about themselves (Villacampa & Gomez, 2016). These results are further elaborated by (De- Santisteban et al., 2018) as they examined the techniques of accessing and grooming the children used by Spanish online offenders. Results indicated that online predators accessed multiple children at the same time. Once approached, they developed persuasion strategies to engage the child more in the conversation. Subsequently, predators thoroughly observed the children’s environment, lifestyle, and vulnerabilities. This strict observation helped them develop some more relevant strategies to engage the child in online sexual activities. As a result, they successfully encountered children in the sexual conduct that further maintained over time in an isolated web-based environment.

Thus, to counteract online child grooming activities, (Gunawan et al., 2018) argued that an Automatic System could play an important role as predators mostly use text-based conversation to interact with minors. For this purpose, 17 characteristics of online sexual Grooming can be easily identified using the Support Vector Machine algorithm and the k-nearest neighbors (KNN) algorithms. For instance, previous studies suggest that the Support Vector Machine algorithm is one of the most effective and straightforward methods along with Linear Kernel with an average accuracy level of 98.6%. Still, we need several process-oriented approaches to examine the patterns of online Grooming and sexual victimization in cyberspaces. Also, critically evaluating the children’s self-expression behavior on online platforms is the need of the day (Ranney, 2021).

Online Sextortion

Today Sextortion in Cyberspace is a common practice due to enhanced internet access and a technology-based environment. However, the research behind online Sextortion, its types, motives, and gratification is still limited. Existing literature describes online child sextortion as mainly driven by either personal sexual gratification or to earn easy money. For example, Lucas Chansler, a thirty-year-old man living in Florida, victimizes female children through his six different social media profiles. All the profiles appeared to be owned by fifteen years old boys who were interested in skateboarding. Chansler used his profiles to trick young girls into sharing their private photos and sextorting them on camera to gratify his deviant sexual interests. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) later identified more than 100 girls victimized by Chansler in the United Kingdom, USA, and Canada (DeTardo-Bora & Bora, 2016). Besides, many online platforms facilitate online child sextortion as practicing child sextortion, saving it on camera, and distribution on other platforms is efficient and sometimes unidentifiable. Traditionally, the efforts related to child sexual abuse were limited, identifiable, and covert. Children were inaccessible in many cases, and the material was of poor quality. However, with the rise of internet technology, accessibility increased, and the quality of content also improved, leading to even stronger chances to facilitate online child sextortion. As a result, today, child online sexual extortion has transitioned from a local concern to a global epidemic (Ali, 2019; Westlake & Bouchard, 2016)

Moreover, Kopecký (2016) differentiated between cyber-grooming, pornography, and "Sextortion" the word “Sextortion” comes from "extortion" or "blackmailing" which happens once a child faces online sexual abuse or shares his private photos that are considered pornographic material. Compared to online Grooming, Sextortion is forced and based on different tactics that may involve blackmailing the child emotionally or in some other manner. More precisely, Sextortion as a criminal offense results from online Grooming. However, Sextortion does not necessarily happen. Some cases also involve victim’s volunteer sexual activities due to Grooming and without sharing any intimate material. Yet, the basic objective of Sextortion involves convincing the minor for a personal meeting as the offender commits not to share the victims’ private material if they agree to involve in the required sexual activity (Kopecký, 2016). As noted by (Hong et al., 2020), victims fear both social consequences and their parents regarding the release of their private pictures or videos. Consequently, the cycle of online child sextortion and abuse does not stop, leading to several psychological problems. Recently, several cases of Sextortion are also highlighted in the mainstream media, indicating the severity of the issue and demanding in-depth considerations (Table 6).

| Table 6 Summary of the Literature Regarding Online Child Sextortion | ||||

| Source | Design/Method | Journal/Publisher | DOI/ISBN/ISSN | Aim |

| (DeTardo-Bora & Bora, 2016) | Review | Digital Forensics | 10.1016/B978-0-12-804526-8.00008-3 | Online child exploitation in Cyberspace |

| (Westlake & Bouchard, 2016) | Review | Social sciences research | 10.1016/J.SSRESEARCH.2016.04.010 | What is online child sexual abuse in Cyberspace? |

| (Kopecký, 2016) | Longitudinal design | Telematics and Informatics | 10.1016/j.tele.2016.04.004. | To examine the online Sextortion of children in the Czech Republic |

| (Hong et al., 2020) | Review Article | Current Opinion in Pediatrics: | 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000854 | To examine what is online child sextortion and what are the characteristics of the predator |

| (O’Malley & Holt, 2020) | qualitative content analysis | Journal of Interpersonal Violence | 10.1177/0886260520909186 | To examine what is online Sextortion |

| (Agrawal, 2020) | Review | Indian Journal of Health, Sexuality & Culture | 10.5281/zenodo.3929135 | What is online Sextortion? |

| (Gottfried et al., 2020) | Review | Sexual Disorders | 10.1007/S11920-020-1132-Y | What are online child pornography and solicitation? |

A case study conducted by (O’Malley & Holt, 2020) examined the patterns of online child sextortion, demands, victims' characteristics, and methods to understand the different relevant aspects of Sextortion. Qualitative data from n=152 revealed four primary themes of predators based on their crimes: transnational criminal cyber sextortion offenders, minorfocused cyber sextortion offenders, intimately violent cyber sextortion offenders, and cybercrime cyber sextortion offenders. The diverse nature of online Sextortion is thought-provoking as many offenders demanded prosecution based on the nature of their crime. Thus, all four types of Sextortion are heinous and require robust legislative implementations according to the characteristics and nature of the offenses. Regarding Sextortion, (Agrawal, 2020) highlighted two primary methods to extort a child in Cyberspace:

1. Offenders might hack the laptop, desktop computer, and mobile device having personal email and data saving platforms. These devices and data-saving drives can have victim's photos and videos that can be further used for extortion purposes.

2. Using social media chatrooms to communicate with the minor, share personal details, groom them, and extort them later. In this context, there are many incidents where predators Sextorted their victims to reveal, share and distribute their photos and videos. However, there are many cases where the offenders Sextorted the victims and shared their photos and videos. Besides, Sextortion and revealing the victim's photos and videos also increase the "Crossover Offending" which is even more harmful, persistent, and hard to counteract due to the internet as a most efficient communication platform (Gottfried et al., 2020).

Impacts of Child Sexual Abuse in the Cyberspace

Online child sexual abuse victims sometimes do not cooperate in disclosing or providing any information related to the incident. Sometimes they are afraid of the predator and ashamed of receiving any striking reactions or quick judgment regarding the sexual abuse. Even minors who disclose the relevant incidents show a harsh attitude towards themselves and used derogatory attributions, including "stupid" or "prostitute" while revealing unsupportive reactions from their parents and others family members (Katz, 2013). However, previous literature, such as a study conducted by (Martin, 2014) also indicates impacts of online child sexual abuse as a less considerable phenomenon. The qualitative data gathered from n=3 child protection workers and n=11 clinicians revealed that they do not consider online Child Sexual Abuse as harmful as nonvirtual child Sexual Abuse. Only one practitioner reported an online sexual abuse case, yet it was about an adult female facing camera abuse and Sextortion. (Martin, 2014) further attributed this to having merely conventional Child Sexual Abuse training and potential literature gap in examining the impacts of Online Child Sexual Abuse. As the term “Online Child Sexual Abuse” indicates, a more heinous, offensive, and secretive type of sexual violence against children, the respondents of the similar research also demanded more research to highlight the adverse impacts of Online Child Sexual Abuse in-depth detail.

As a result, studies addressed the impacts of Online Child Sexual Abuse. For instance, (Hanson, 2016) highlighted the impacts of Online Child Sexual Abuse in psychological consequences. As noted that, Online Child Sexual Abuse has similar consequences as non-virtual abuse can have. Prior evidence from young people who have faced online sexual abuse echoed several in-depth findings such as suicides, hostility, self-harming behavior, panic attacks, depression, disgust, shame, and others. Sometimes, these impacts are at their peak when parents do not support victims. To empirically examine the impacts of Online Child Sexual Abuse (Jonsson et al., 2019), conducted cross-sectional research in Sweden.

The researcher randomly selected n=5175 high school children from the local level institutions. Results indicated that individuals from the index group were having poor relationships with parents compared to the participants from the reference groups. Also, the students who faced online sexual abuse had low self-esteem (M=15.25, SD=7.72) than those who did not face any sexual abuse in Cyberspace (reference group). Poor physical health was another significant impact of online child sexual abuse among the index group members (p<0.001). Likewise, there was very little difference in depression among the children who face both (online and offline sexual abuse M=13.29, SD=6.65) and who faced online sexual abuse (M 8.33, SD=7.43, p=0.008). Thus, (Jonsson et al., 2019) concluded that these consequences could become more critical once the child gets sexually abused by the online predator. Sharing online photos or on-camera sexual abuse can further lead to Sextortion and even more severe psychological consequences. As noted by (Pietronigro et al., 2019), children’s online exposure to offenders further increases the risk of dangerous interactions. Online Grooming, pornography, Sextortion are all today crucial public health issues that need more substantial consideration. Consequently, children facing the relevant situations can also become offenders due to problematic internet usage.

A study conducted by (Joleby et al., 2020) further extended the existing propositions regarding the impacts of Online Child Sexual Abuse. The researchers gathered data by qualitative interviews, conducted a thematic analysis, and later divided long-term and short-term impacts into three prominent themes, i.e., everything collapsed Self-blaming and fear of resurfacing their photos. First of all, all the respondents indicated that they were different and confident before the online sexual abuse. For most respondents, "Everything collapsed" after the sexual abuse and they have become "suicidal" One of the participants also mentioned that she had developed depression after the five years of her online sexual abuse. Many also reported self-ignorance and low self-esteem. Notably, trauma was shared among all but at different stages with different levels of severity. Under the second theme, "Self-blaming" individuals revealed that they knew an online sexual activity is taboo, yet they continued and kept it a secret (Table 7). Besides, unknowingly sharing the personal content further led them to believe that they were "stupid" as many of them argued that they could have stopped the abuse if they would have turned off their computers.

| Table 7 Summary of the Literature Regarding Impacts of Online Child Sexual Abuse | ||||

| Source | Design/Method | Journal/Publisher | DOI/ISBN/ISSN | Aim |

| (Katz, 2013) | Case study | Children and Youth Services Review | 10.1016/J.CHILDYOUTH.2013.06.006 | To examine the predator's narratives from victims of online abuse and their impacts. |

| (Martin, 2014) | Qualitative study, in-depth interviews | Child and Youth Services | 10.1080/0145935X.2014.924334 | Understanding the child sexual abuse images on the internet and their impacts on the victims |

| (Hanson, 2016) | Book | John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. | 10.1002/9781118977545.CH6 | To highlight the psychological impacts of online child sexual abuse |

| (Jonsson et al., 2019) | Cross-sectional design | Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health | 10.1186/s13034-019-0292-1 | To examine the impacts of online child sexual abuse and further leading to offline sexual abuse. |

| (Pietronigro et al., 2019) | Review | Annali di Igiene: Medicina Preventiva e di Comunità | 10.7416/AI.2020.2353 | To highlight online Grooming as a growing social concern and its impacts |

| (Hamilton-Giachritsis et al., 2020) | Case study technique | Child Abuse & Neglect | 10.1016/J.CHIABU.2020.104651 | Perceptions of psychology professionals regarding risks of online child sexual abuse |

| (Joleby et al., 2020) | Qualitative method | Frontiers in Psychology | 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.606218 | To examine the effects of online child sexual abuse on the psychological health of the victims. |

| (Joleby et al., 2021b) | Mixed-method research | Psychology, Crime & Law | 10.1080/1068316X.2020.1781120 | Experiences and psychological condition of children who experience online sexual abuse |

Moreover, the third theme, “Resurfacing their photos" a primary reason for anxiety was the fear of resurfacing the photos as they were concerned about what if others may watch these photos? As a result, one of the respondents was unable to face men, leading to lower selfconfidence. Similarly, a few participants were also confronted with self-shaming during the lawful processing as their photos were an essential part of the case proceedings. They had to sit outside, knowing that everyone inside was watching their private photos. However, the professionals' perceptions about Online Child Abuse are still problematic, witnessed by (Hamilton-Giachritsis, et al., 2020). Qualitative data from n=45 professionals showed a strong consistency with the previously conducted study (Hanson, 2016). The results indicated that the professionals do not consider online sexual abuse as much serious as offline abuse. Yet, they agreed that the impacts could be the same such as psychological distress and self-harming behavior. Besides clinicians, the legal proceedings about Online Child Sexual Abuse should also consider its psychological consequences. It is also important to mention that; courts often adduce the psychological impacts of Child Sexual Abuse in an offline environment that further leads the prosecutors and lawmakers to think of online abuse as less harmful. This consideration will not only highlight Online Child Sexual Abuse as equally detrimental, but also it will help the victim to raise their voice to attain full justice, as the victim deserves to be heard and served well to mitigate the psychological impacts of sexual abuse (Ali et al., 2021; Joleby et al., 2021).

Discussion

Previous research has well-witnessed the types, processes, stages, patterns, and impacts of Online Child Sexual Abuse. However, online crimes against children are still a complex, critical, and important issue as they are constantly shaped, altered, and modified by the perpetrators (Martellozzo, 2019). As a result, today, the internet is a powerful platform for producing and sharing child sexual abuse-based material that can work instantaneously and anonymously accessible for individuals with deviant sexual interests. Even online child sexual abuse wings also obligate the individuals to share the relevant content to get their membership. As a result, a safe online environment is merely a dream for the new generation (Durkin & DeLong, 2012). The current article also cited the literature witnessing perceived risks of internet usage for children. We extensively discussed the role of Cyberspace in facilitating different types of child sexual abuse, indicating the position of internet technology in accelerating and further complicating sexual crimes against children. For this reason, (Hamilton-Giachritsis et al., 2020) and many others consider it mainly as "Technology Facilitated Child Sexual Abuse" raising several concerns towards internet usage and risk factors among minors.

The current research resonates with the systematic review findings conducted by (Maniglo, 2009) where he highlighted the impacts of offline child sexual abuse. Based on the cited literature, we found the extent to which Online Sexual Abuse is directly attributed to several health-related consequences. This article also shows that the internet is a significant vehicle for online child predators to molest children in at least four ways: creating the child abuse-based content (Pornography) and sharing it with other predators and online platforms, accessing and grooming children for online child sexual abuse, and blackmailing the minors to continue sexual activities to avoid resurfacing of their private content (Joleby et al., 2020; O’Malley & Holt, 2020; Seto et al., 2010).

Besides, we also found that Online Sexual Abuse is not less harmful than offline sexual abuse. According to (Hamilton-Giachritsis et al., 2020), Online Child Sexual Abuse has a detrimental impact as much as offline sexual abuse. No matter how the offenders perpetuated their crimes, their impact on victims can be ruinous, leaving them to feel depressed, mortify, and even suicidal (Martellozzo, 2019).

Besides, disturbed sleep, eating disorders, nightmares, intrusive thoughts, and difficulty keeping up with studies are other prominent impacts (Hamilton-Giachritsis et al., 2020) that are well witnessed by (Joleby et al., 2020).

The destructive nature of these impacts can be determined by the fact that studies also witness that Online Child Sexual Abuse can affect the victims in childhood and even adulthood. Several Macro-level studies in 2013 witnessed seven attempted suicides and a similar number of completed suicides due to online Sextortion. Also, substance abuse is another significant impact of Online Child Sexual Abuse (Hanson, 2017). Another major impact is witnessed by (Jonsson et al., 2019), as they also anticipated and revised the concept of “Abused-Abuser” in an online environment, indicating the victim’s tendency to abuse children in the future. However, some studies witnessing Online Child Sexual Abuse as a less considerable concern for the clinicians and other relevant professionals is another major issue. As noted by (Martin, 2014) the effects and patterns of online and offline child sexual abuse differ in severity and techniques.

Yet the conceptualization of Online Child Sexual Abuse and its impacts need much more consideration, especially by the clinical practitioners. The inability of these practitioners to differentiate between the nature and impacts of online and offline child sexual abuse shows that they have an incomplete and tentative understanding of Online Child Sexual Abuse that further hinders proposing far-reaching implications for the minors' well-being and development.

Practical Implications

The problem of Online Child Sexual Abuse is a novel, complicated, and rapidly changing phenomenon. Despite internet technology is facilitating many purposes of our life; Online Child Sexual Abuse has also increased and modified hand-in-hand. Online predators involved in online abuse have deviant sexual interests, leading them to constantly search for vulnerable children, making Cyberspace questionable regarding children’s security and the violation of their rights. However, the existing gap in the literature is causing a lower understanding concerning the prevalence and intensity of Online Child Sexual Abuse among the practitioners, which is problematic. In this regard, it is essential for the legal experts and penitentiary psychology practitioners to evaluate the causes, dynamics deeply, and characteristics of offenders to ensure secure Cyberspace for the children. Besides, in-depth analysis of the impacts of Online Child Sexual Abuse victims can further help determine the problem's depth and consequences. The urgency to provide practical solutions demands more studies to facilitate the profound reflection of Child Sexual Abuse and its potential impacts. As for the preventive measures, we also suggest some practical implications that can help to counteract effectively against Online Child Sexual Abuse. We suggest these implications by keeping the current finings and discussion under consideration:

1. As mentioned earlier, a limited understanding of Online Child Sexual Abuse among clinicians is a thoughtprovoking phenomenon. Consistent efforts are required to conduct more studies addressing Online Child Sexual Abuse and its impacts on increasing awareness, especially among the practitioners (Martin, 2014).

2. We found that Online Child Sexual Abuse encompasses different types of sexual offending, and their impacts are equally detrimental. Based on this evidence, we suggest courts and legislative bodies worldwide evaluate the impacts of OCSA to conduct the jurisprudential proceedings further accordingly (Jackson, 1998).

3. Notably, victims hesitate to speak about Online Sexual Abuse due to striking reactions and shaming, which further demands a sensitive response, especially from the parents. Online Sexual Abuse is one of the prominent sub-types of fatal abuses, obligating the parents and other family members to carefully support and respond to any relevant incident (WHO, 2002).

4. Automatic systems such as Support Vector Machine algorithms, Intrusion Detection Systems, configuration checking tools, Anomaly Detectors, Honey Pots (lures), and others can be helpful to detect and trace any criminal activities against children. Using Support Vector Machine algorithms, as suggested by (Gunawan et al., 2018), can be used to identify online Grooming and patterns.

5. Parents and teachers should help children to understand the "Stranger-danger" concept. In terms of the Online environment, this concept is well-validated by (Villacampa & Gómez, 2016), as they discussed its usefulness among high school students in Catalonia, Spain. Consequently, children can avoid interacting with strangers and also refrain from sharing their photos and videos.

6. Children's accidental exposure to pornographic content, i.e., emails, advertisements, promotional videos, etc., demands safe-browsing measures. Service providers can filter the relevant content through Internet Content Filter Tools as recommended by (Stark, 2007).

7. “Domain Name System over Https” can help to protect children from sexual abuse and identify the predators. As the relevant system not only helps to block the pornographic material, also detects any copyright violation, antisocial activities, or distribution of prohibited content online (Ali et al., 2021).

8. Educational institutions should invest in creating and disseminating media literacy-based content in schools. Debate programs and discussions regarding sexual content on digital media and its potential influences can also increase awareness regarding Sexual Abuse on the internet.

Conclusion

Although we have extensively discussed the prevalent types and impacts of Online Child Sexual Abuse, this article also contains some limitations. First, we have selected only five databases for the article selection process, while there are many other platforms where the relevant literature is extensively available. Second, we selected literature only from 2000 to 2021; however, research studies during the 1990s also highlighted online child sexual abuse. Third, the study is based on a review process and does not contain any primary data resources or human subjects that narrow down its scope. Yet, this study will add more to the existing literature as Online Child Sexual Abuse is a briskly growing phenomenon. More studies will highlight its impacts and dynamics that will help the policymakers, clinicians, and legislative bodies ensure a better future for the children. Thus, we suggest studies in the future concerning OCSA awareness among parents and clinicians. Similarly, case studies from different regions will bring out in-depth details about the OCSA that will help to counteract it more effectively.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

Agrawal, S. (2020). Online sextortion. Indian Journal of Health, Sexuality & Culture, 6(1), 14-21.

Aiello, L.M., & McFarland, D. (2014). Detecting child grooming behaviour patterns on social media. Social Informatics, 8851(9), 412-427.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ali, S. (2019). Understanding paedophilia through different perspectives. Lambert Academic Publishing.

Ali, S., Haykal, H.A., & Youssef, E.Y.M. (2021). Child sexual abuse and the internet-a systematic review. Human Arenas, 4(4), 1-9.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Amos, O.O. (2009). Harmonizing the interests of free speech, obscenity, and child pornography in cyberspace: the new roles of parents, technology, and legislation for internet safety. The Scientific World Journal, 9(10), 1260-1272.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Biswas, S., Sarfraz, Z., Sarfraz, A., Malanyaon, F., Vijayan, R., Gupta, I., Arif, U., Sarfraz, M., Yatzkan, G., & Sanchez-Gonzalez, M. A. (2020). Risk and outcomes of COVID-19 patients with asthma: A meta-analysis. Asthma Allergy Immunology, 18(11), 0-8.

Black, P.J., Wollis, M., Woodworth, M., & Hancock, J.T. (2015). A linguistic analysis of grooming strategies of online child sex offenders: Implications for our understanding of predatory sexual behavior in an increasingly computer-mediated world. Child Abuse & Neglect, 44(6), 140-149.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Brasil, S.D., Lunardi, P.A., Lunardi, V.L., Arejano, L., Ximenes, C.B., Andréa, S., & Portella, J. (2017). Violence against children and adolescents : Characteristics of notified cases in a southern reference center of Brazil violence against children and adolescents: Characteristics of cases reported at a reference center in southern Brazil Violence c. Enfermería Global, 16(46), 432-444.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Burke, A., Sowerbutts, S., Blundell, B., & Sherry, M. (2002). Child pornography and the internet: Policing and treatment issues. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 9(1), 79-84.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Choo, K.K.R. (2009). Online child grooming: A literature review on the misuse of social networking sites for grooming children for sexual offences.

De-Santisteban, P., Del-Hoyo, J., Alcázar-Córcoles, M.Á., & Gámez-Guadix, M. (2018). Progression, maintenance, and feedback of online child sexual grooming: A qualitative analysis of online predators. Child Abuse and Neglect, 80(5), 203-215.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

DeTardo-Bora, K.A., & Bora, D.J. (2016). Cybercrimes: An overview of contemporary challenges and impending threats. Digital Forensics: Threatscape and Best Practices, 12(8), 119-132.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Durkin, K.F., & DeLong, R.L. (2012). Internet crimes against children. Encyclopedia of Cyber Behavior, 1(4), 799-807.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Elliott, I.A., & Beech, A.R. (2009). Understanding online child pornography use: Applying sexual offense theory to internet offenders. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 14(3), 180-193.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Baines, V. (2008). Online child sexual abuse: The law enforcement response. Journal of Digital Forensics, Security and Law, 4(4), 7-37.

Gottfried, E.D., Shier, E.K., & Mulay, A.L. (2020). Child pornography and online sexual solicitation. Current Psychiatry Reports, 22(3), 1-8.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gunawan, F.E., Ashianti, L., & Sekishita, N. (2018). A simple classifier for detecting online child grooming conversation. Telecommunication Computing Electronics and Control, 16(3), 1239-1248.

Hamilton-Giachritsis, C., Hanson, E., Whittle, H., Alves-Costa, F., & Beech, A. (2020). Technology-assisted child sexual abuse in the UK: Young people's views on the impact of online sexual abuse. Children and Youth Services Review, 119(12), 105-451.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hamilton-Giachritsis, C., Hanson, E., Whittle, H., Alves-Costa, F., Pintos, A., Metcalf, T., & Beech, A. (2020). Technology-assisted child sexual abuse: Professionals' perceptions of risk and impact on children and young people. Child Abuse & Neglect, 119(1), 104-651.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hanson, E. (2016). The impact of online sexual abuse on children and young people. Online Risk to Children: Impact, Protection and Prevention.

Hanson, E. (2017). The impact of online sexual abuse on children and young people: Impact, protection and prevention. In J. Brown (Eds.), Online Risk to Children.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hong, S., Lu, N., Wu, D., Jimenez, D.E., & Milanaik, R. L. (2020). Digital sextortion: Internet predators and pediatric interventions. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 32(1), 192-197.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jackson, B. S. (1998). Truth or proof? The criminal verdict. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law, 11(33), 227-273.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Joleby, M., Landstrom, S., Lunde, C., & Jonsson, L. S. (2021). Experiences and psychological health among children exposed to online child sexual abuse–a mixed-methods study of court verdicts. Psychology, Crime and Law, 27(2), 159-181.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Joleby, M., Lunde, C., Landström, S., & Jonsson, L. S. (2020). All of me is completely different: experiences and consequences among victims of technology-assisted child sexual abuse. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(9), 1-15.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jonsson, L.S., Fredlund, C., Priebe, G., Wadsby, M., & Svedin, C.G. (2019). Online sexual abuse of adolescents by a perpetrator met online: A cross-sectional study. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 13(1), 1-9.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Katz, C. (2013). Internet-related child sexual abuse: What children tell us in their testimonies?. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(9), 1536-1542.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kopecký, K. (2016). Online blackmail of Czech children focused on so-called sextortion (analysis of culprit and victim behaviors). Telematics and Informatics, 34(1), 11-19.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Krone, T. (2004). A typology of online child pornography offending. Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, 279(9), 1-6.

MacPherson, S. (1989). The convention on the rights of the child. Social Policy & Administration, 23(1), 99-101.

Maniglo, R. (2009). The impact of child sexual abuse on health: A systematic review of reviews. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(7), 647-657.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Martellozzo, E. (2019). Online child sexual abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect: Forensic Issues in Evidence, Impact and Management, 12(9), 63-77.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Martin, J. (2014). It’s just an image, right? Practitioners’ understanding of child sexual abuse images online and effects on victims. Child and Youth Services, 35(2), 96-115.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Merdian, H. L., Curtis, C., Thakker, J., Wilson, N., & Boer, D. P. (2013). The three dimensions of online child pornography offending. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 19(1), 121-132.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

O’Malley, R. L., & Holt, K. M. (2020). Cyber sextortion: An exploratory analysis of different perpetrators engaging in a similar crime. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(5-6), 1-2.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pietronigro, A., Tiwanaa, N., Mosillo, M., & Castillo, G. Del. (2019). Little red riding hood in the social forest. Online Grooming as a public health issue: A narrative review. Annali Di Igiene, 32(3), 305-318.

Ranney, J.D. (2021). The process of exploitation and victimization of adolescents in digital environments: the contribution of authenticity and self-exploration. Child and Adolescent Online Risk Exposure, 12(9), 33-55.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rimer, J.R. (2019). In the street they’re real; in a picture they’re not: Constructions of children and childhood among users of online child sexual exploitation material. Child Abuse & Neglect, 90(4), 160-173.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Seto, M.C., Reeves, L., & Jung, S. (2010). Explanations given by child pornography offenders for their crimes. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 16(2), 169-180.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Stark, P.B. (2007). The effectiveness of internet content filters. Usenix Foci, 11(2), 943-979.

Sumner, S.A., Mercy, A. A., Saul, J., Motsa-Nzuza, N., Kwesigabo, G., Buluma, R., Marcelin, L. H., Lina, H., Shawa, M., Moloney-Kitts, M., Kilbane, T., Sommarin, C., Ligiero, D. P., Brookmeyer, K., Chiang, L., Lea, V., Lee, J., Kress, H., & Hillis, S. D. (2015). Prevalence of sexual violence against children and use of social services - seven countries, 2007-2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 64(21), 565-569.

Thorn. (2019). Child pornography and sexual abuse material.

Townsend, C., & Rheingold, A. (2013). Darkness to light all the statistics. Darkness to Light, 36(9), 260-266.

UNICEF. (2020). Sexual violence against children.

Villacampa, C., & Gómez, M.J. (2016). Online child sexual grooming: Empirical findings on victimization and perspectives on legal requirements. International Review of Victimology, 23(2), 105-121.

Ward, C. L., Artz, L., Leoschut, L., Kassanjee, R., & Burton, P. (2018). Sexual violence against children in South Africa: a nationally representative cross-sectional study of prevalence and correlates. The Lancet Global Health, 6(4), 460-468.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Westlake, B. G., & Bouchard, M. (2016). Liking and hyperlinking: Community detection in online child sexual exploitation networks. Social Science Research, 59(9), 23-36.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

WHO. (2002). Child abuse and neglect by parents and other caregivers.

Received: 04-Oct-2021, Manuscript No. JLERI-21-8630; Editor assigned: 06-Oct-2021, PreQC No. JLERI-21-8630(PQ); Reviewed: 20- Oct-2021, QC No. JLERI-21-8630; Revised: 24-Feb-2022, Manuscript No. JLERI-21-8630(R); Published: 03-Mar-2022