Research Article: 2023 Vol: 29 Issue: 3

A Study on the Socio-Economic Strategies used by Rural Senior Citizens for Coping with Sustainable Livelihoods in Zimbabwe: An Investigation

Stella Chipo Takaza, University of Zimbabwe

Citation Information: Takaza. S.C. (2023). A study on the socio-economic strategies used by rural senior citizens for coping with sustainable livelihoods in Zimbabwe: An investigation. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 29(3), 1-22.

Abstract

The study investigated the socio-economic strategies used by rural senior citizens for coping with sustainable livelihoods in Zivagwe and Shurugwi districts south west of Zimbabwe. The study is informed by the Sustainable Livelihoods Approach developed by the Department of Foreign International Development, (1999) in the United Kingdom. The main objectives were; to establish the socio-economic activities employed by Rural Senior Citizens for survival and coping strategies for their health and wellbeing; to explore the challenges experienced by rural senior citizens under socio-economic hardships. And finally, determine policy interventions and programmes that could be designed to enhance the wellbeing of rural senior citizens. While quantitative data was collected through questionnaire survey and qualitative data was collected through in-depth interviews and key informant interviews, focus group discussions; transect walks for direct observation and audio-visual methods and the snowballing methods. A minimum of 90 rural senior citizens (45men and 45 women) with ages 60+years and 20 key informants were sampled to represent. The study found that although there are varied humanitarian food aid programmes implemented in the rural communities, rural senior citizens continue to experience difficulties in accessing sustainable socio-economic livelihoods resources for better health and wellbeing. Often, rural senior citizens usually are assumed to have accumulated some savings from Pension and Other Benefits Scheme for old people aged 65years and above who would have contributed during their lifetime. The study is calling on Government and stakeholders to prioritize policies and programmes for senior citizens in the rural areas.

Keywords

Rural Senior Citizens, Survival, Coping, Strategies, Sustainable Livelihoods, Pension Scheme.

Introduction

Excessive efforts are required to investigate the socio-economic activities employed by the Rural Senior Citizens (RSCs) with or without contributory Pension and Other Benefits Scheme (POBS) in Zimbabwe. The POBS is a scheme available to all residents aged 65years and above who would have contributed during their lifetime in the formal sector. The employer and the employee agree to contribute up to a ceiling on earnings that are adjusted from time-to-time. Studies reveal that Pensions and other Benefits Scheme is not reliable for reducing poverty among the older people (Demba, 2013). The vast majority of people are usually not formerly/informally employed and as a result, Rural Senior Citizens (RSCs) end up employing complex and diverse survival and coping mechanisms under socio-economic hardships. Dhemba and Dhemba, (2015) confirms that “it is conveniently believed that poor countries have more pressing problems and competing demands on state resources, which makes it difficult to provide for older persons”. In terms of RSCs’ basic needs, UNECE Policy Brief on Ageing (2017) provides that older people with no pensions cannot even afford a meal per day and others find it difficult to support themselves. Most rural older populations have less access to services and activities and the situation is further aggravated when combined with poorer socio-economic and environmental conditions. Today, the values of individualism have exposed many older populations to social insecurity. As a result, many questions have been asked; what are the strategies used by the RSCs for survival and coping with sustainable livelihoods under socio-economic hardships? What are the challenges experienced by RSCs in accessing food for health and wellbeing? What can be done for older people who retired to improve their health and wellbeing? What are the possible policy and interventions that could be used for the rural retired people for longevity in good health? This study investigates the socio economic activities employed by RSCs for survival and coping with sustainable livelihoods in Zivagwe and Shurugwi districts south west of Zimbabwe.

Backgroung Information

Agro Ecological Region and Major Farming Activities in Case Study Districts

In Zivagwe and Shurugwi districts, the agro-ecological conditions are attributable to the prevailing underlying factors. Statistics illustrate that in Zivagwe, 94.4 percent populations are food secure whilst 5.6 percent are food insecure and in Shurugwi district, 94.4 percent populations have been food secure whilst 5.6 percent were food insecure (The Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee ZIMVAC, 2015). These figures demonstrate that RSCs in rural districts are deprived of their socio-economic opportunities for survival and coping with available livelihoods resources, especially those who live in remote drought-stricken areas. The greater portion of the districts are characterized by Agro-ecological regions 111, 1V and 1V where rainfall is both low (650-800m per year) and unreliable which used to predict a green revolution in the same regions. About 79% of the households experience some shocks and family units depend on farming activities for their livelihood (Mararike, 2011; ZIMVAC, 2015). National assessments found that anybody travelling through the rural districts feel, hears and sees that every inhabitant is a farmer and the primary occupation of families is farming. Previous studies show that the commercial farming sector under agro-region 1 and 11 was once a source of exports and foreign exchange for Zimbabwe (Mudimu, 2004). But however, because of the recurrent droughts, the food zone areas have become a net importer of food products in the form of food aid.

Social Context

Zimbabwe has 16 official languages; Shona, Ndebele and English which are spoken by the ethnic groups across the country where Shona people constitute 99.4%, White 0.2% and others counting Indians 0.4% and 99.7 % of the population is of African origin (Census Report, 2012). The Shona and Ndebele people inhabit the Midlands Province and practices create pillars of people’s cultural and religious beliefs namely; Christians and African traditional religion. About 85% Zimbabweans are Christians and 62% of the population attends religious services. The main languages in Zivagwe and Shurugwi districts are Shona, Ndebele and English. In the two districts, Christianity is mixed with traditional beliefs where non-Christian religion involves spiritual intercession. It has been observed that members of the young generation practice Christian religion. In contrast, members of the older generation practice both Christian and traditional religion and regard traditional values as their primary symbol they protect. It has been noted that the younger generation have a tendency to root themselves in modern cultures which is bound to dilute the African culture of the young generation.

Natural resources

Natural resources contribute to the livelihoods among the rural communities in Zivagwe and Shurugwi districts. The two districts are rich in natural resources because of the Great Dyke belt which is one such area famous for its chrome and gold as well as undisputed agricultural activities which lend an atmosphere of farming and mining. Chrome is mined and transported by a road network which links to the rural areas and attracts tourists and ordinary people to express solidarity with production and nature. Zivagwe and Shurugwi rural and urban centers are connected to enhance transportation of chrome, gold and agricultural products to their final destinations.

Socio-economic context

Socio-economic, macro-economic imbalances including high budget deficits, balance of payment deficits, inflation and low economic growth impact on the nutrition and wellbeing of RSCs who retired with limited Pension and Other Benefits Scheme. The bulk of RSCs with low incomes suffer either seasonal or semi-permanent sustainable livelihoods as the economy comprises of a monetary sector, which co-exists with a rural economy. Most rural households become net food buyers since due to severe droughts fail to produce enough food to meet their needs to the next harvest season (Mararike, 2011; ZIMVAC, 2015). The districts hinge on mineral exports such as gold, agriculture and tourism as the main foreign currency earners. The rural money economy is usually very low and the problem is aggravated by poor infrastructures and badly managed road network which is supposed to enhance free movement of goods and services to the local level. Many people especially RSCs appear to face plenty of social and economic challenges since the majority are never formerly employed and contributed during their lifetime. RSCs families then engage in sporadic livelihood activities such as gold panning and chrome mining which is offensive to the environment. However, even if there is food in the market, a lot of families with low incomes are regularly not able to access food requirements (Muza, 2012; Nyikahadzoi et al, 2013). RSCs have no other income earnings to fall back on during drought episodes. Government and NGOs operating in Zivagwe and Shurugwi district promoting food security together with emergency food aid in addition to cash transfers in lieu of food aid (Kapungu, 2013). RSCs are supported by Social Welfare and Voluntary or Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) are providing food assistance when there is drought (Kapungu, 2013).

In disaster situations the Government usually declares a state of national disaster and launches appeals to the international community to offer food relief (Graciano da Silva et al, 2016; ZIMVAC, 2015). The international community give the same level of attention to people grappling with reduced livelihoods resources. The ever-escalating limited livelihoods dilemma necessitates the broad increase in the proportions of socio-economic insecure families to some parts of the districts which are considered self sufficiency and even export surpluses to neighboring countries Karen & Donald (2001). Some parts of the districts are now experiencing shocking limited sustainable livelihoods driven by the El Nino weather pattern which is a temporary reversal in direction of ocean currents across the Pacific Ocean (Graziano da Silva, J., & Ndaka, 2016).

Theoretical Framework

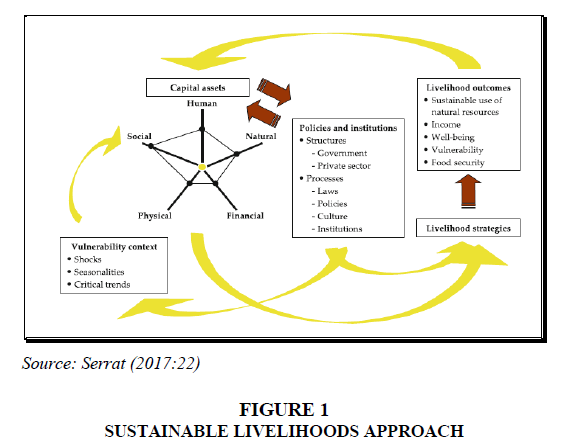

The study is informed by the Sustainable Livelihoods Approach (SLA) developed by the Sustainable Livelihoods Approach developed by the Department of Foreign International Development, (1999) in the United Kingdom. Serrat (2017) proffer that the SLA is a way of thinking about objectives, scope and priorities for development-based interventions. Figure 1 shows the SLA for the people at risk.

The SLA stresses that vulnerability is the probability of a person or family falling below a minimum food security level within a certain time frame. The DFID (1999) emphasize that the model answers questions on what sustainable livelihoods are and how they can be achieved, ideally and practically and can be drawn from several developmental approaches. The SLA model in this context explains how RSCs households produce food and emerges as a developmental framework for analysing household food security and famines through works of Sen, (1982); Scoones, (1998). The SLA emphasizes on the socio-economic vulnerabilities of people and in this study investigates how RSCs households of the retired people produce food for nutrition and physical wellbeing. It is applied to investigate the socio-economic opportunities for survival and coping with the sustainable livelihoods employed by RSCs households to supplement their life saving pensions if at all they worked during their lifetime. A livelihood encompasses the capabilities like assets together with both material and social resources and activities used by a household for a living (Sen, 1981).

Vulnerability is the probability of a person or household falling below a minimum food security within a certain time frame (Chambers & Conway, 1992). The SLA emphasizes that individuals, family households and communities are exposed to vulnerabilities that are closely linked to a number of external hazards such as civil unrest, conflict, severe drought, cyclone disasters, food insecurity, and variation in food prices. Governments and institutions like international food relief agencies, donors, business community and families usually make sure that communities in general are provided with humanitarian livelihood resources for nutrition and physical wellbeing. The retired RSCs who have many needs but limited livelihoods resources are usually overlooked as those who conduct means test assume that RSCs have use their pension savings. Studies reveal that non-contributory scheme to the older people aged 65 years and above is available to those who do not receive any other income from the state (Holzmann, et al., 2013). The study investigates the socio-economic opportunities employed by RSCs for survival and copings RSCs who retired and explore the challenges they face in order to determine possible interventions that could be used for them in Zimbabwe. The findings will inform Government and stakeholders in programming that ought to address RSCs’ problems as well as scholars who may want to conduct further researches on the wellbeing of retired RSCs in Zimbabwe.

Research Methodology

Data Collection Methods

While informed by the Sustainable Livelihoods Approach developed by the DFID, (1999) and the study objectives, the study collected data from 90 RSCs and 20 key informants to represent. While, quantitative data was collected using questionnaire tool guides, qualitative data was collected using in-depth interviews key informant interviews, participant observation, FGDs and snowballing methods. The sampling design was based on geographical location, meaning that the respondents were representative of RSCs in the two districts of the Midlands Province.

Location of the Study

The study was conducted in the communal, resettlement and semi-urban areas of Zivagwe and Shurugwi districts of the Midlands Province. Both districts constitute communal, old and new resettlement areas where farming is practised on both commercial and subsistence sources. The study location was preferred because the districts tend to have high numbers of RSCs who engage in various socio-economic and non-economic activities for survival and coping with sustainable livelihoods as compared to other districts in the province. The districts were also selected because of their proximity to the main roads which transport food to and from the rural areas, when the food zone areas used to produce food on a commercial basis. Zivagwe and Shurugwi districts have semi-urban Chrome and Gold mining locations inhabited by small-scale gold panners and miners who depend entirely on these illegal activities as sources of livelihoods.

Study Population

At least 90 RSCs with ages 60+ years and 20 key informants were drawn from Government Departments, Churches and community leaders to partake in the study. The sampled population RSCs were economic migrants from neighbouring countries like Malawi and Zambia who once worked for many years in the mining areas like Mashava, Shurugwi, and Zvishavane or from as far as Masvingo, Bulawayo, and Gweru. Since the economic migrants could not go back to their countries or origin, the majority were resettled in the surrounding rural areas. The totals were 120 respondents representing 26.7% from the 450 of the main study.

Data Analysis

Still guided by the theoretical considerations and the study objectives, data was analysed electronically and manually. The research objectives and questionnaire guides determined the analysis technique. Quantitative data was analysed electronically from particular to general using a computer software package known as the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS.pc). The collected information was coded and recorded the most repeatedly mentioned issues. Qualitative data was analysed using thematic content analysis; focusing on themes and sub themes set by the questionnaire tool guides.

Ethical Issues

Ethically, permission was sought from the Provincial Administrator (PA), District Administrators (DAs), Councillors and traditional chiefs who granted authorization to access the respondents. Those sampled respondents made decisions to participate in the study after enough information was given that data was for purely for academic purposes. Verbal and written consent were used for the protection of the subjects using the respondent consent form. Human rights and the potential risks and benefits were explained prior to the interview. Maximum confidentiality and anonymity were observed using numbers instead of names on the questionnaire tool guides and uniformity of the information was assured by using the same questionnaires in the same format for all subjects.

Results and Discussion of Findings

Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

Primarily, good rapport conducive for a mixed method study was established to investigate the socio-economic activities employed by RSCs for survival and coping with the livelihoods hardships in order to determine possible interventions and strategies that could be used to improve the health and wellbeing of RSCs in the rural districts. At least 90 RSCs and 20 key informants to represent were selected for in-depth interviews, participant observation, FGDs and Snowballing. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the respondents.

| Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics Of Respondents (No-120) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Categories | Frequency (Percent) |

| Sex | Female | 55 (12.2) |

| Male | 65 (14.4) | |

| Marital Status | Widowed | 45 (10.0) |

| Divorced | 45 (10.0) | |

| Never Married/Single | 20 (5.3) | |

Table 1 explains that 90 RSCs and 20 key informants identified as widows, divorced, single and those who never married constituted 55(12.2% female) and 65(14.4%) contributed in the study. While the widowed constituted 45(10.0%), the divorced were 45(10.0%) and those who never married were 20(5.0%). These results indicate that the impact of livelihoods resources on the divorced and widowed was severe while it was moderate on those who never married because the later could engage in other sources of economic activities to supplement their pension and other benefit schemes.

Sources of Local Support

The study found that RSCs receive local support to improve health and wellbeing. The results of Table 1 show the sources of local support for RSCs by frequency and percentage.

Table 2 shows that RSCs depend on food production since they exhausted their pensions and other benefits schemes saved during their lifetime. Some survive through the localized schemes such as Zunde raMambo Model which is a Shona word that means a large gathering of people taking part in a common activity or may refer to plenty of grain stored for future use. The Zunde means an informal, in-built social, economic and political mechanism. Its purpose is to ensure that a community have adequate food reserves that cushion the vulnerable people in times of livelihoods scarcities. The Zunde practice ensure that food security for a village is guaranteed at all times. The Chief allocates a piece of land for cultivation at the Chief's compound and the yield from this land is stored in granaries.

| Table 2 Sources Of Own Support For Rscs By Frequency And Percentage |

||

|---|---|---|

| Sources of Support | Frequency | Percent |

| Own food production | 60 | 66.7% |

| Remittances | 8 | 8.9% |

| Friends and relatives | 11 | 12.2% |

| Market System | 9 | 10.0% |

| Local Community (Zunde raMambo) | 2 | 2.2% |

The study found that RSCs receive external support to improve their health and wellbeing from different programmes. The results of Table 3 show the sources of external support.

Table 2 shows that RSCs fall under the emergency food aid programmes provided by Government and international food agencies. While free food distribution constituted (54(45.0%), food for work programme was 20(16.7%) and Grain Loan Scheme was 30(25.0). Also, public assistance and community health care constituted 03(2.5%) and cash transfers for food constituted (10(8.3%). The results indicate that free food distribution was the highest 54(45.0%) while public assistance and community health care were the least which indicate the need for more interventions that address the problem the RSCs’ health and wellbeing who never had contributory Pension and Other Benefits Scheme (POBS) for survival and copings with livelihoods resources.

RSCs’ Economic and Non-Economic Activities

The study found that RSCs with low incomes engage in various economic and non-economic activities for survival and coping with sustainable livelihoods resources. Results of Table 4 shows the economic and non-economic activities for health and wellbeing in case study districts.

Table 3 reveal the type of economic and non-economic activities of the RSCs who retired with no contributory benefit schemes to cushion them. RSCs start engaging in economic activities with high consumption and energy demands. Productive RSCs engage in small scale gold panning, while others have no energy to perform heavy duties which shows a significant reduction in the level of food security of acceptable standards for their wellbeing. Others engage in economic and non-economic activities that contribute to family earnings to supplement their meagre pension scheme savings. The economic activities are nutrition gardens, agriculture, labor for cash, livestock, cottage industry, remittances from relatives, friends non-economic include caring for grandchildren, attending funerals, weddings, political meetings, memorial services detailed below.

| Table 3 Sources Of External Support By Frequency And Response Rate |

||

|---|---|---|

| Nature of the Programme | Frequency | Response Rate (%) |

| Free Food Distribution | 54 | (45.0) |

| Food for Work Programme | 20 | (16.7) |

| Grain Loan Scheme | 30 | (25.0) |

| Public Assistance | 03 | (2.5) |

| Community Health Care | 03 | (2.5) |

| Cash Transfers for food | 10 | (8.3) |

| Total | 120 | (100) |

| Table 4 Selected Remfs’ Economic And Non-Economic Activities |

|

|---|---|

| Economic Activities | Non-Economic Activities |

| Nutrition gardens | Caring for grandchildren, |

| Brewing traditional beer for sale | Attending funerals, |

| Livestock | Weddings, |

| Art and craft, pottery | Political meetings |

| Collecting wild fruits and selling | Socializing with friends and relatives |

| Cash for labour | Anniversaries |

| Buying and selling for survival | Church meetings |

| Remittances | Memorial services |

| Family Assets | Political meetings |

Nutrition Gardens

The study found that most RSCs engage in nutrition gardens to supplement their pension benefits if one was a member. Many RSCs grow varieties of vegetables for nutrition and income-generation to supplement their pension savings. Results of Figure 2 shows a selected nutrition garden where RSCs grow vegetables for consumption as well as sale surplus in order to generate income for other essentials like paying medical bills, transport, grinding mill and community tax/contributions etc.

Figure 2 shows varieties of vegetables grown in their nutrition gardens include; green vegetables, tomatoes, onions, okra, potatoes among others. RSCs undertake these activities for income and nutrition for health and physical wellbeing. Sometimes vegetables have low output, as most households produce them in winter when surface water is available (Mutami, 2015). Others reduce their output which is a challenge as highlighted during the interviews. Productive RSCs look physically better than those who no longer have the energy to work for themselves in their domestic gardens who show small bodies and some looked frail, awfully deprived and old. Others have deficiency in their diet that lack nutrition which is normally shown by a small body size, low levels of energy, and reductions in mental functioning which some nutritional studies argue they reduce people's ability to work and learn. As a result of memory gap or dementia, some RSCs could not even remember the kinds of food which they had consumed in the past 24 hours. However, as food stocks sometimes run out before time after a pathetic harvest, some indicated that they rely on food assistance and wild fruits in season.

Livestock

The study found livestock as an essential source of nutrition and income for the wellbeing of RSCs with low incomes. Results of Table 5 shows selected livestock acquired by RSCs in case study districts.

Table 5 shows that livestock are an important source of nutrition as well as social and economic transactions such as marriages, family rituals, ceremonies, and exchange in times of crises such as famine and/or illnesses. Keeping livestock in the country is a necessity because of high unemployment levels in the country. Most of the people above 60 years of age are in the informal sector and do not have access to contributory Pension and Other Benefits Scheme (POBS). Mararike (2011) argue that keeping livestock can be used for paying debts, performing traditional ceremonies like marriage celebrations, paying lobola, angered spirits or traditional anniversaries. Then again, small livestock such as goats and chickens are used as "buffers" in times of crises and are sometimes sold first before cattle or food grain to raise funds for pressing family needs such as school fees and medical bills. Livestock diversification include cattle, goats, pigs, chickens and sheep during rainy season is crucial for improved nutrition (Mutami, 2015). The study noted that livestock provide milk, meat, draft power, and manure and also serve as sources of cash income which play a vital role in the social and cultural spheres. Many RSCs asserted that they take rotating responsibilities of keeping livestock for value addition and beneficiation. Livestock enhances family food and nutrition through increased food production and family income. Animal health conditions show signs of deterioration and cattle deaths increased drastically during drought and excessive rainfall (WFP, 2017). Livestock weight and health conditions deteriorate and cattle deaths are registered in the south and south-east districts (WFP, 2017). A few exchanges for food in the event of severe drought and extreme livelihoods famines. Some RSCs looked after animals that survived during the flood’s disasters but however, no one reported to have treated livestock from animal diseases to avoid drastic animal decline as many reported shortages of animal medicines. RSCs expressed some challenges in animal raising and decline of livestock due to diseases such as the tick borne and food and mouth diseases. To raise livestock can require large amounts of energy, water, feeds among others which the ageing and immobile women find it difficult to contain unless they have young adults to help them (FAO, 2016). Others keep small domesticated livestock like chickens, pigs and goats and some re-iterated that very few could sell or exchange an animal for food during drought as a way of survival and coping with food shortages as these are regarded as some form of wealth. Studies confirm that livestock is used for draught animal power; especially in light of the fact that farm mechanization is minimal in resettled farming areas (Mutami, 2015).

| Table 5 Selected Livestock Owned By Rscs Per District |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Livestock | Zivagwe | Shurugwi | Total | Percentage (%) |

| Goats | 25 | 12 | 37 | 9.87 |

| Chickens | 14 | 11 | 25 | 5.6 |

| Pigs | 5 | 11 | 16 | 3.6 |

| Donkeys | 7 | 16 | 23 | 6.1 |

| Cattle | 8 | 11 | 19 | 5.1 |

| Total | 59 | 61 | 120 | 26.7 |

Agriculture

The study found agriculture is the backbone of the economy that contributes to food consumption and cash. Results of Table 5 shows the traditional crops by RSCs to supplement pension scheme savings.

| Table 5 Selected Traditional Crops Grown By Rscs |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crops Grown | Zivagwe | Shurugwi | Total | Percentage (%) |

| Maize | 96 | 96 | 192 | 45.7 |

| Sorghum | 56 | 74 | 130 | 28.9 |

| Finger Millet | 75 | 84 | 159 | 35.3 |

| Rapoko | 85 | 65 | 150 | 33.3 |

| Groundnuts | 90 | 87 | 177 | 39.4 |

| Monkey nuts | 92 | 91 | 183 | 40.7 |

| Sweet potatoes | 88 | 94 | 182 | 40.4 |

| Pumpkins | 99 | 96 | 195 | 43.3 |

Table 5 shows that agriculture is heavily linked to family size and gender dynamics because resources such as labor and capital are provided by close family members and kinsmen (Mutami, 2015). RSCs engage in agricultural activities to enhance food security and can still be involved in land preparation, sowing, planting, fertilizing, weeding, harvesting, winnowing, food processing and storage for future use in the event of extreme food shortages. Food production, processing and storage are central to the survival and copings of RSCs. Crop production in communal areas is mainly by own family labor (Mutami, 2015). Many RSCs engage in food production, processing and storage, marketing as a common activity to prepare for future use all through the season. The processed food for value addition include maize, millet, sorghum, monkey nuts/ground nuts, vegetables, mushrooms etc. which they can dry in the sun for future use.

The study found RSCs produce traditional grains like finger millet and ground nuts as a fallback crop in times of severe droughts, indicating that these traditional grains can be stored for a long time in the traditional granaries for future use. Some crops like maize, sorghum and millet would be sending for grinding on traditional grain stone at home and at times would dry the grain in the sun as a way to preserve the food for future use. The results for Figure 3 show traditional grains which can withstand harsh weather conditions and can be stored for longer periods for future use in the event of severe drought and food scarcities.

Figure 3 shows traditional grains which can be processed and stored in granaries for a long time without getting spoiled for future use. Aluga & Kabwe, (2016) confirm that processing food, preservation and packaging of foods is undertaken to prevent spoilage by microorganisms (bacteria, yeast, and molds), and enzymes, temperature, and biochemical changes impart a keeping quality or shelf-life to foods. RSCs explained that if food processing is not done properly, food by its nature begins to spoil the moment it is harvested. Most RSCs reported that they process and package the harvested traditional grains in sacks in which they can apply chemicals such as (Chirinda-matura) dust for preservation. Other RSCs expressed that the methods used to process and store the harvested crops are good though some indicated that it is poor because many families no longer have the traditional granaries (matura) for food storage. Some packaging techniques influence physical and chemical changes, including migration of chemicals into foods which might not be good for nutrition and health of the people who consume the food (Aluga & Kabwe 2016).

Cottage Industry

Many RSCs engage in cottage industry which is a small trade or development activity carried out at a person's residence or homestead. The results of Figure 4 reveal that some RSCs engage in cottage industry for income and to purchase food for consumption.

Figure 4 shows that RSCs who reside in agro-regions IV and V engage in cottage industry using locally available resources found in dry areas. Cottage industries are made financially viable through village industrial units or production units to advertise or sale. Productive RSCs engage in traditional small-scale industry like art and craft which is demanding, using natural products which are more important to the family income for their survival and to cope with food shortages. RSCs expressed that the process of making traditional art and craft is heavy and painful exercise for them. Art and craft use locally available raw materials and indigenous skills and RSCs highlighted that they face difficulties when going to collect raw materials from the thick forests to make items such as baskets, pottery, door mats, table mats, floor mats; a trade which was beyond their energy and capacity. RSCs argued that due to old age and limited mobility, they could not engage in such long and tough processes of cutting fibers prepare and weave into baskets or mats to sell for income or to barter trade for maize, vegetables or clothes as a way of survival and coping with food shortages under economic and environmental hardships.

Labor Power

The results show that RSCs perform agricultural activities for themselves and others in return for food or cash. Figure 4 shows a combined labor power effort that assist RSCs to prepare land for planting crops.

Figure 5 shows a shared labour power or cooperative which Mutami (2015) highlight that it is increasing in both communal and resettlement tenure systems. The pattern of labour power is a mixture of livestock-rearing and rearing, thatching roofs, weeding, cutting firewood and ploughing/planting crops on other people’s fields in exchange for money or food. Some RSCs reported they are sometimes assisted by some active family members who engage in food for work or work for cash on their behalf for other households or join programmes introduced by Government or NGOs for rural communities.

Non-Economic Activities

Some RSCs reported that they engage in various non-economic activities within their family networks which gives them a sense of purpose. Some of non-economic activities include not only limited to taking care of grandchildren while their mothers go to work but also attend funerals and weddings, church services, traditional ceremonies and political meetings which several reported that these add value and a sense of purpose to their life styles. Non-economic activities are a source of inspiration to the entire society, especially to the young. Some RSCs mentioned that this adds value and dignity to them because they as well provide guidance and moral support to their children and society at large. RSCs added that they also engage not only to memorial ceremonies, but similarly attend community events such as women’s associations and political meetings for personal benefit and as party of their social responsibility. Some RSCs revealed that they pursue non-economic activities that strengthen or motivate them to move on with a better life despite their challenges. Others indicated that they have little to regret because they have lived a fulfilling and economically productive life in their life time when they were still young and energetic. Others called for the acceptance and re-integration of ostracized, neglected RSCs into families and communities in the latter part of their lives which reassures them dignity, sense of belonging and being loved.

The study found survival skills, shocks and copings are used by RSCs who face difficulties in accessing available food for nutrition and physical wellbeing. The percentage of population reliant upon food aid reflect these changes (Cochrane, 2017). Although they purchase food, many reported that they rely on government and food aid which is unreliable in some years. RSCs reported that they consume fewer foods and others indicated that they beg, borrow or engage in casual labor for food and gold panning as it is the case across the two districts. RSCs added that they involve in barter trading, eating wild fruits in season, selling livestock, eating less in order to save for tomorrow and providing labor for food. Some highlighted that they rely on food/cash assistance from food for work or cash for food programmes launched by Government and international food relief agencies. A few RSCs reported that they do not receive anything and one RSC had this to say;

“I do not receive any remittances from my children, grandchildren, relatives and friends because of the economic situation which is affecting everybody. The breadwinners were affected by the Economic Structural Adjustment Programme and those who were sending remittances were retrenched and are back here in the rural areas because these days there are no jobs”.

There was a wider acceptance of diverse initiatives on the markets. Scores of RSCs reported that they have social networks such as family friends, relatives, community members, Church members among others from where they could borrow or exchange for food as a coping strategy. The social networks for those in developing countries, tend to be a major coping mechanism.

Family Assets

The family assets are the major sources of income for sustenance amongst RSCs with low incomes. Results of Table 6 shows that the family assets owned by RSCs could be traded for income to purchase food for some to supplement their Pension and Other Benefits Scheme of their life time if at all they had any.

| Table 6 Selected Assets Acquired By Rscs For Per District |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Assets | Zivagwe | Shurugwi | Total | Percentage (%) |

| Houses | 12 | 13 | 25 | 5.6 |

| Hoes | 20 | 30 | 50 | 11.1 |

| Plough | 12 | 20 | 32 | 7.1 |

| Sickle | 15 | 10 | 25 | 5.6 |

| Axe | 15 | 21 | 36 | 8.0 |

| Table and chairs | 3 | 5 | 8 | 1.8 |

Table 6 is fundamental as it shows the different kinds of family assets and income sources which have a larger impact on the wellbeing of RSCs with low incomes. One of the RSCs had this to say.

“My family assets include two round huts, a hoe, an axe, sickle, traditional grinder, plates, pots and other small items. I do not have any other assets that contribute economically except to receive food aid from the Government and food relief agencies. I walk 2km to the distribution Centre. My request would-be that village heads be given powers to receive food and allocate to us at village level”.

Tangible and intangible assets have stores of value or claims which could be mobilized in order to sustain. Most RSCs have tangible and intangible family assets which they saved during their lifetime and other receive from their children, friends, relatives or neighbors which could be disposed of in exchange for food or cash. Property of any family include tangible goods (land, cultivated areas, agricultural equipment, livestock, machinery, buildings, family appliances and other heavy-duty goods) and its financial assets (WFP, 2017).

The study found no matter how few or insignificant, RSCs view assets as a form of wealth and family assets for the next generation, which should not be traded or bartered in any way. Some RSCs vowed that even if plenty opportunities are available for them to sell family assets to purchase food or to exchange for food; this was an outrage for them to dispose of family wealth especially of the deceased family members. The study found African people socially construct the consequences of certain realities that if they dispose of family assets, they are likely to evoke the wrath and punishment of the ancestors and the deceased. The study found that many RSCs have varied opinions with regards to question on how most retired would dispose of family assets of the deceased without the fear of retribution and vengeance from the deceased person. Several RSCs disputed that family asserts; especially those of the deceased members of a family could not be sold or exchanged for food for fear of angering the spirits of the deceased. One RSCs in a state of heartbreaking had this to say;

“All my three children have died leaving behind their property which I am now keeping in one of my huts. This is property which I cannot sell or exchange for food, because I may offend the spirits of my dearly departed children, which may torment me. I do not even know what I will do with those goods”.

Some RSCs dreaded to retail property of the deceased or to exchange material belongings of their late children who had passed on because they socially constructed that a misfortune would ensue them. Traditional beliefs sanctioned the society to respect assets of the deceased based on the social construction theory of reality that assets of a person who has passed on should not be sold or vandalized otherwise misfortune would haunt the offender. Other RSCs feared that the avenging spirits of the dead would bring misfortune to the entire family. The study observed that even though family assets, especially of the deceased, like cattle and property were available within each family, these did not help them in any way to obtain sufficient food for nutrition and physical wellbeing when there was severe drought and extreme food shortages. Cattle could be milked or used for draught power, but could never be used disposed of in any way. Through in-depth interviews and FGDs, varied views from women were expressed that those family assets are considered a source of intergenerational wealth for the family and therefore are charged with the responsibility to maintain them safely.

The results show that the remaining family assets, either shared or inherited can only be disposed of after the death of the surviving partner. RSCs’ assets land, granary, cattle, plough and scotch cart remained family assets which could be used to enhance food security whilst personal assets like household utensils, personal clothing are shared among the deceased’s relatives. Livestock such as cattle or donkeys remain assets of the deceased, though they continue to be used as draught power. Mararike (2011) explains that cattle are significant family assets in different social relations like family rituals, marriages, ceremonies trading in times of catastrophes such as food shortages and chronic illnesses. The majority RSCs aver that they could not exchange family assets for food as assets of the deceased were not disposed of for fear of angering the spirits of the dead who acquired the assets during life time.

Remittances

The study found remittances play an essential role in RSCs’ households as a source of livelihoods for survival and coping with life under socio-economic hardships. Remittances are personal flows of money from migrants to their families and friend (Tambama, 2015). Many RSCs reported that family members help each other in times of need even if it is an individual issue. Numerous RSCs anticipated to be receiving remittances from their children which could be important means of survival and coping with life challenges (Tambama, 2015) figures indicate that 50 percent of the population receive remittances. Many RSCs reported that they need financial and material support for them to survive and cope with socio-economic challenges. WFP, (2017)’s stress that vulnerability of certain population groups such as older women, children, and families with little or no livestock with even limited access to receiving remittances make them more susceptible to food insecurity most of the time. Studies show that Remittances are significant in both consumption per capita and human capital formation (Tambama, 2015). Some RSCs revealed that they receive remittances from their children and working relatives in diaspora. Others however indicated that remittances they receive during the food shortage periods is not even enough to cater for all their food security needs. Some RSCs reported that they use remittances to pay for medical bills, school fees, travelling, clothes, food and agricultural inputs. One RSCs expressed that the meagre remittances she was receiving was not adequate and as a result only receive insufficient remittances which she can largely use for the basics. Several RSCs further declared that for a decent living lifestyle, the family requires a minimum of $ 210.00 per month to procure all the family essentials. Studies confirm that enough remittances have a positive and significant on the wellbeing of the poor families (Tambama, 2015). Another RSC confirmed that the family requires $210.00 to survive and cope well per month. Some RSCs expressed that during targeting and means testing, some RSCs look like as if they are excluded and have not received any assistance as some are considered to be well off than others. Some are assumed that they should depend on their life savings and working children or receiving remittances from elsewhere The World Bank, (2013) explain that; “targeting seeks to deliver benefits to a selected group of participants, in particular poor and vulnerable people, however showed dissatisfaction and articulated that the individuals are excluded from targeting as these are regarded as people who acquired some form of family assets like houses, furniture, livestock looked as if they are wealthier than others. In the selection of beneficiaries, Government and NGOs need to make efforts to include RSCs, build robust grievance and redress procedures. RSCs expressed that they are surviving and coping with livelihoods challenges under difficult condition since they are assumed to have some savings acquired from POBS which allowed them to acquire more wealth and better houses more than others.

Problems Encountered by RSCs by Frequency and Archetype

The study found that RSCs face problems which need interventions strategies. Some of the challenges range from escalating cost of basic commodities, exclusion from receiving livelihoods, lack of climate change mitigation and adaptations strategies to lack of agricultural equipment and inputs to plant crops before the oncoming of the rain season. The results of Table 7 show the challenges faced by RSCs in case study districts.

| Table 7 Selected Summaries Of Challenges Faced By Rscs By Frequency And Archetype |

||

|---|---|---|

| Challenges | Frequency | Archetype Quotation |

| Lack of climate change mitigation and adaptations strategies | 18 | “RSCs need programmes that address the climate change phenomenon so as not to be caught unaware which result in the decline in food productivity” |

| Lack of agricultural equipment and inputs to plant crops before the oncoming of the rain season | 22 | “Government and food security stakeholders to prioritize the agricultural needs of RSCs before onset of the rain season” |

| Exclusion from receiving livelihoods resources | 14 | “Government to introduce a non-contributory pension scheme for all RSCs as a form of security” |

| Poor dietary food intake | 10 | “When I go to the clinic, I only get medicine but not information on proper dietary food intake” |

| Poor Health and Wellbeing | 20 | “I have poor health; Arthritis, BP, heart, poor eye sight, aching legs and loss of energy” |

| Escalating cost of basic commodities | 99 | “Our financial status needs to be improved for us to meet the high cost of living” |

| Gender Discrimination and Inequality | 45 | “As female RSCs, we need gender inequality and discrimination against our entitlements to be removed urgently” |

Table 7 shows the challenges faced by RSCs and how these challenges could be addressed to improve the health and wellbeing of RSCs on retirement. Mudimu (2004) and Muza (2012) agree that the country never had a clearly articulated food security policies especially those that relate to older people. RSCs indicated that they face difficulties in accessing sufficient socio-economic opportunities for their health and wellbeing. Some mentioned the effects of the Economic Structural Adjustment Programme (ESAP) as a legal framework that disadvantaged them significantly. RSCs reported that they no longer have the energy to perform heavy duties in the agricultural sector while others cited being excluded in programmes that enhance livelihoods resources for their wellbeing.

Escalating Cost of Basic Commodities

The escalating cost of basic commodities on RSCs, with low or no pension scheme was one of the pressing challenges. The outbreaks of infectious disease, flash flooding and food price increases across districts increase the overall effect but remain little understood. Added that an increase in prices of basic commodities and products are looming in Zimbabwe. Many RSCs lamented that they are grappling with escalating costs of basic commodities which heavily impact on then since they never had the opportunity to be formerly employed and no longer have the energy to perform heavy agricultural activities as a source of livelihoods and the situation is also bad for RSCs with low pension incomes. The Sky-scraping rate of basic commodities is exacerbated by extreme poverty in Zimbabwe, where (WFP, 2017) report that 72 percent of the populations live on less than US$1.25 a day. One RSC had this to say;

“There are many food shops which sell groceries but they need money. But I have no one to give me money with which to buy the food from shops”.

Gender Discrimination and Inequality

The study found gender discrimination and inequality as some of the fundamental issues raised by RSCs in rural remotes areas. Muza, (2009) corroborate that lack of access to sufficient sources of livelihoods such as land, capital, and assets by women has not been accorded equal opportunities as a married woman is regarded as a stranger within the new family systems. Gender discrimination and equality interventions negatively impact on RSCs with inadequate livelihoods resources to cater for their basic needs is in a daunting mode. One of the challenges faced by RSCs is that many do not acquire property or assets of their own even those that relate to inheritance because many are regarded as “strangers” in a new family system. In an African mind set, being patriarchal, property is largely inherited by men rather than women which already is a challenge related to gender discrimination and inequality amongst RSCs who retired with no contributory benefits accorded to them. The gender inequality and discrimination challenging female RSCs is that quite a lot of RSCs do not own any property or assets for them to survive and cope with life challenges under economic hardships. Made and Glen wright (2015) added that gender treaties and protocols tend to overlook and marginalize the exclusive demographic character of RSCs who face many challenges of surviving and coping with food shortages under economic and environmental hardships. So quite a lot of RSCs were widowed who mentioned that they identify themselves as marginalized and discriminated against their entitlements. Policies and frameworks are supposed to focus on special needs of RSCs who are never formally employed; an entity that must be prioritised in any case.

Health and Physical Wellbeing

The health and physical wellbeing of RSCs is another challenge faced by RSCs who retired with or without forced contributory Pension and Other Benefits Scheme (POBS). Poor health and physical wellbeing of the retired with livelihoods to cushion them escort them to food scarcity. Studies reveal that “Hunger and food shortages affect the health and physical wellbeing of many families” and malnutrition and hunger related diseases caused 60 percent of the deaths (Zekeri, 2014); UNICEF, 2007). RSCs with inadequate health services and medications face numerous challenges related to inadequate diet for nutrition and physical wellbeing. The health issues for example High Blood Pressure (BP), arthritis, poor eyesight, poor hearing, heart diseases and many others impact negatively on the wellbeing of RSCs above the ages 60+ years. Older persons are imagined to have the capacity to tolerate the pain they suffer based on notion that their qualitative perception of pain is diminished. A male key informant had this to say;

“I have known RSCs in this area for many years. I occasionally communicate with them at various meetings or home visits. Many RSCs complain of unsatisfactory health services. Even though there was severe in 2015/2016 drought spell, but nobody died of hunger and 2016/2017 was an exceptionally good rainy season. The groups that have been at risk of food shortage mostly are the widows and single mothers. Some are able to work for themselves but others are unable. They occasionally receive food aid from the Government and NGOs. A few have inherited property which they sell to purchase food and to send children to school” (Interview with a respondent on 27 March 2017).

The medical history and information on nutritional and health practices prove that many RSCs have weak diets and lack access to food rich in micronutrients like iodine, iron, and vitamin A which are essential for a health life. RSCs revealed that varieties of food consumed had limited micronutrients for a balanced diet which contributed to disease patterns peculiar to old age. RSCs with inadequate diets developed kwashiorkor, rickets, anemia, arthritis and succumbed to ill health and early death (Nyikahadzoi et al., 2013). Some who got ill reported that they sought medical attention from the nearest clinics or hospitals whilst others sought spiritual attention from their Churches and a few visited traditional healers. One RSC indicated that when she falls sick, she resorted to self-care since she could not afford to go to the hospital as she was economically deprived with no sources of income for medical bills. Many RSCs revealed that they were not formally employed had very with low incomes which deprived them from their right to benefit from the health services as costs of medical bills were escalating coupled with some clinics experiencing staff and medicines shortages. Access to health services and wellbeing plays a significant role in guaranteeing that older people are healthy enough to engage in food production. However, even if RSCs have diverse dreams to shift from receiving external assistance, they still need a wholesome type of approach which incorporates the social, economic, environmental, physical and psychological components of survival and coping with the challenges.

Most RSCs are sometimes bypassed and neglected with nothing to fall back after they retired. WFP (2016) assert that rural people constitute the bulk of the older women at risk of exclusion by being failed by intervention policies and livelihoods entitlements meant for the older people. Stakeholders need to equalize and put in place clear policies targeted at RSCs who retired with low incomes. RSCs were however skeptical as they felt they were sometimes excluded from the food relief programmes intended for all as they were assumed to have some pension scheme benefits. Some survive and cope with the assistance from their dependents who are a source of human capital and labor force whilst a handful receive some remittances from relatives and friends. The study noted some form of segregation in the provision of food security policies and interventions amongst different demographic groupings like RSCs which is rising significantly. The Government and food security specialists are required to design and implement comprehensive food security interventions and sustainable strategies targeting RSCs who retired with or without some pensions and other benefits Scheme to cushion them.

Policy Implication and the Role of Social Work in Zimbabwe

In Zimbabwe, socio-economic policies and framework for the health and wellbeing of RSCs with ages 60+ years is limited against the background of unavailability of pensions and other benefits scheme to fall back on. Although there exist some institutional frameworks that have been developed at the national and local level to support communities, the socio-economic challenges and resource constraints to provide them is daunting. There are no comprehensive policy intervention strategies that specifically focus on older people who retire for a descent lifestyle. Dhemba (2013) suggest that Government and stakeholders can and must put in place policies and programmes that benefit older people who retire with low incomes for them to live longer. Although Government and stakeholders are committed to supporting older people, policies and mitigation strategies which specifically target RSCs with ages 60+years are required. Comprehensive socio-economic policies and programmes could be planned and designed to help them access their basic livelihoods needs such as health care, nutritious food, descent shelter, transport and social networks for rural care among others. Although some institutional policy and programme interventions have been introduced in the form of free food distribution, food for work, grain loan scheme, these are sometimes socially excluding RSCs bypassed by social pensions and reliable sources of income. As quite a number have never been formally employed and do not have pensions and other benefits scheme to cushion them, many RSCs fight for economic opportunities to survive and cope with sustainable livelihoods that help to improve their health and wellbeing. Sen (1982) argue that lack of sustainable entitlements like communal land, credit, income, family support systems etc directly contribute towards the problem of survival and copings among the vulnerable groups who have been deprived of their opportunities. The effective and influencing policies and programming are needed to reduce the problem of poor health and wellbeing in the event of unpredicted socio-economic hardships. The study is calling on Government to mainstream RSCs into policy programming and development by making sector planning more responsive to addressing the socio-economic for survival and copings after retirement. Policy formulation to include steps that improve the health of RSCs who suffer diseases such as BP, heart diseases, and deficiencies caused by food shortage stresses and poor diets. Thus, policies on livelihoods support, rural skills development centres and recreational services etc are essential for RSCs who retired because many were not formally employed and were in the informal sector.

Policies and programming should prioritize RSCs more than those who are still active and that Government should consider appointing representatives of the retired people to cater for their special needs and offices in each district as an added advantage.

Conclusion

This study investigated the survival and coping strategies used for the health and wellbeing of rural senior citizens in Zivagwe and Shurugwi districts in Zimbabwe. Although RSCs benefit from local socio-economic initiatives and Government-led support programmes such as public assistance, free food distribution, public works or food for work and the Grain Loan Scheme (GLS), many struggle to survive and cope with livelihoods as quite a lot have not been working during their lifetime to benefit from the forced contributory Pensions and other Benefits Scheme (POBS). RSCs’ health and wellbeing continue to be affected because of the prevailing socio-economic challenges experienced in the country. The results of the study are calling on Government and concerned stakeholders to prioritize policies and programmes specifically for rural senior citizens which could restore meaningful health and wellness outcome to them.

References

Aluga, M., & Kabwe, G. (2016). Indigenous food processing, preservation and packaging technologies in Zambia.

Chambers, R., & Conway, G. (1992). Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical concepts for the 21st century. Discussion Paper 296, Institute for Development Studies.

Cochrane, L. (2017). Strengthening Food Security in Rural Ethiopia. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctorate of Philosophy in the College of Graduate Studies, University of British Columbia, Okanagan.

Conway, G. (2005). Improving Food Security in Africa: Issues and challenges for poor farmers. Murray T. B.G. and Denis J Murphy, D. J. (2017).

Demba, J. (2013). Social protection for the elderly in zimbabwe: issues, challenges and prospects. African Journal of Social Work (AJSW), 3(1).

Dhemba, J., & Dhemba, B. (2015) Ageing and Care of Older Persons in Southern Africa: Lesotho and Zimbabwe Compared. Social Work and Society International Online Journal, 13(2).

Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). (2016) Food Nutrition and Agriculture. Available at: www.fao.org/docrep/u3550t/u3550t02html. Accessed 21 February 2019.

Graziano da Silva, J., & Ndaka, M. (2016). Modern Farming- Climate change adaptation, mitigation in Zimbabwe- Food shortages worsen as drought grips Zim, 7. Daily news. Harare.

Holzmann, R., Palmer, E., & Robalino, D. (2013). Nonfinancial Defined Contribution Pension Schemes in a Changing Pension World: Vol.1, Progress, Lessons, and Implementation. World Bank, Washington, DC. Accessed from http://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/pdf/ 10.1596/978-0-8213-9478-6 on December, 2016.

Kapungu, S.T. (2013). A study of rural women farmers’ access to markets in Chirumanzu. Sustainable Development Planning and Management, Stellenbosch University. Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za.

Karen, E.C., & Donald, R. (2001). Nutrition among Older Adults in Africa: the Situation at the Beginning of the Millennium. Nutrition and Dietetics Unit, Department of Medicine, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa.

Made, P.A., & Glenwright, D. (2015). The SADC Protocol on Gender and Development Southern Africa Gender Protocol 2015 Barometer – Zimbabwe. ISBN 978-0-9922433-4-0 South Africa: Johannesburg. Available at: www.genderlinks.org.za www.sadcgenderprotocol.org. 7Accessed 20 October 2017.

Mararike, C.G. (2011). Survival Strategies in Rural Zimbabwe: The Role of Assets, Indigenous Knowledge and Organizations Best Practices Books; Harare

Mudimu, G. (2004). Paper forum for food security in Southern Africa www.odi.org.uk/food-security-forum -Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Zimbabwe.

Mutami, M. (2015). Smallholder Agriculture Production in Zimbabwe: A Survey Department of Rural and Urban Development Consilience. The Journal of Sustainable Development, 14(2), 140-157.

Muza, O. (2012). Rural impact assessment of agriculture water systems in a climate change context. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology, 1373-1385.

Nyikahadzoi, K., Samati, R., Motsi, P.D., Siziba, S., & Adekunle, A. (2013). Strategies for improving the economic status of female-headed households in eastern Zimbabwe: The case for adopting the IAR4D framework’s innovation platforms. Journal of Social development in Africa, 27(2).

Scoones, I. (2009). Livelihoods and Rural Development. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 36(1). 171-196.

Sen, A.S. (2006). Sustainable agriculture and rural livelihoods. Agricultural Economics Research Review, 19, 205-217.

Sengupta, P. (2016). Food security among the elderly: An Area of Concern. Journal of Gerontology & Geriatric Research, 5, 320.

Serrat, O. (2017).The sustainable livelihoods approach. Asian Development Bank: Knowledge Solutions.

Tambama, J. (2015). The impact of remittances on zimbabwean economic development. pdf. MSc Economics Department of Economics Faculty of Social Studies University of Zimbabwe Publications.

UNECE Policy Brief on Ageing No. 18 March, (2017) Older Persons in Rural and Remote Areas. Available at: OLDER%20PERSONS%20IN%20REMOTE%20AREAS%20DOC.pdf.Accessed 20 May 2019.

UNICEF. (2019). The Standard Live. Two Million Children under Five Suffering from Acute Malnutrition in Afghanistan. Available at: https://www.unicef.org.uk/press-releases/two-million-children-under-five-suffering-from-acute-malnutrition-in afghanistan/. Accessed22October 2019.

World Food Programme (2017). Conflict and Hunger: Breaking a Vicious Cycle-conflict+ and Hunger+ Web+ String (1).pdf.

Zekeri, A.A. (2006). Livelihood Strategies of Food Insecure Poor, Female-Headed Families in Alabama’s Black Belt” UK Centre for Poverty Research Discussion Paper Series, DP2006-09 Retrieved (Date) from http://www.ukcpr.org/Publications/DP2006-09/pdf Accessed 07/01/2016

Zimbabwe National Statistical Agency National Report (2012) Population Census Office, Harare.

Zimbabwe Parliament Research Department (2011), Chirumanzu Constituency Profile Harare.

Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee -ZIMVAC, 2018). The Rapid assessment final Pdf.https://reliefweb.int/report/zimbabwe/zimbabwe-vulnerability.Accessed 21/02/2019.

Received: 07-March-2023, Manuscript No. AEJ-23-13284; Editor assigned: 08-March-2023, PreQC No. AEJ-23-13284(PQ); Reviewed: 20-March-2023, QC No. AEJ-23-13284; Revised: 22-March-2023, Manuscript No. AEJ-23-13284(R); Published: 25-March-2023