Research Article: 2020 Vol: 26 Issue: 3S

A Social Approach to Addressing Water and Sanitation Infrastructure Backlog A Case of A Rural Municipality in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa

Masibulele Fiko, Walter Sisulu University

Sanjay Balkara, Walter Sisulu University

Beauty Makiwane, Walter Sisulu University

Samson Asoba, Walter Sisulu University

Abstract

This study adopted Glaser and Strauss’ (1967) grounded theory technique to derive social and community based concepts for addressing the water and sanitation backlog at a rural Municipality in the Eastern Cape. Data was collected from thirty (30) community representatives through a focus group discussion. The data collected this way was analysed through concepts of theoretical sampling and theoretical sensitivity. Socially and community routed techniques such as social dialogue, social learning, use of indigenous knowledge systems, community participation and social entrepreneurship were found to be critical for addressing problems related to the water and sanitation backlog in the community. The study recommends that the South African should adopt community driven and socially responsible strategies to addressing he water and sanitation challenges associated with water and sanitation backlog in the Municipality

Keywords

Infrastructural Backlog, Community Participation, Social Responsibility, Sanitation.

Introduction

The World Economic Forum (WEF) recognises infrastructure development as the second pillar in determining a country’s competitiveness (Schwabb, 2019). The present study is specifically aimed to provide theoretical concepts that are relevant to addressing the water and sanitation infrastructure backlog in a South African rural municipality. Access to clean and safe water is a constitutional right specified under Section 27(1) (b) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996. South Africa, however, faces serious water and sanitation infrastructure backlog in a number of its rural communities, mainly in black townships (South Africa Human Rights Commission (SAHRC, 2018). Reports indicate that the backlog originated from the historical background of the country which was characterised by segregation service delivery. The SAHRC in 2014 undertook an investigation into the water and sanitation situation in which a number or infrastructural challenges were established. This study focuses on social based conceptual strategies to address the water and sanitation backlog in the country. In so doing, it switches attention from government driven initiatives to community led strategies for addressing the infrastructure backlogs. The study was premised on the recognition of financial constraints facing South Africa especially with against reports of reduced economic growth which is likely to complicate efforts to improve the water and sanitation situation in the country. The option of adopting community and socially driven ways of addressing the challenges related to the water and sanitation problem was considered. The objective of study was to investigate the role of community and social concepts in improving water and sanitation infrastructures backlogs at a poor rural municipality in the Eastern Cape Province.

Background

General infrastructure development has always been considered a key factor for raising living standards (Bogeti & Fedderke, 2005). In 2005 Bogeti and Fedderke (2005) observed the water and sanitation backlog in South Africa against the country’s benchmark to be an upper middle economy. Most studies into the water and sanitation situation have been conducted as commissioned by the government and human rights groups such as the SAHRC. In some cases and inorder to promote local rural water and sanitation infrastructure as local government usually hires the private company through contracts to carry out a particular task, usually for a period of some years. The contracting years vary according to the duration of that project. Normally the minimum is five years to a maximum of thirty years. In terms of these contracts the public sector sets performance criteria for the activity and scrutinizes bidders on how to supervise contracts and remunerates clients according to the agreed fee for the service. The public sector does not give the offer randomly. It compares the bidding and takes the best that can result to a greater efficiency in service rendered (Fourie & Tsheletsane, 2014).These groups conducted their studies to inform government the situation and invite it to consider budgeting and other policy strategies to improve the circumstances of the communities .The present study takes anew shift and seeks to take another perspective which is based on empowering local communities to take charge of the water and sanitation problems that they face. This approach is inspired by the observation that the government faces multiple challenges in quickly solving the water and sanitation challenge. As such inexpensive and readily available community based solutions appeared important. Infrastructure and economic development and sustainability depend on the availability of funds and the ability to use it effectively, which requires good financial management. Financial management fulfils an important role in the public sector, because without public funds to cover operational and capital costs, and without appropriate personnel, no public institution can render effective services.

Water Services and Sanitation Services

Water equity requires that each person shares access and entitlements to water, and benefits from water use. Existing legislation provides for the allocation for water in all community groups. In many parts of South Africa, much of the available water has already been allocated for someone's use. Mason (2013) claims that water for domestic or primary consumption always receives priority. Yet, despite the fact that water for human consumption is but, a small proportion of the total available, many communities have totally inadequate access to drinking water even though many farmers use large volumes of water for irrigation and stock farming even in the more arid areas of the country. This is a contradiction which is deeply felt and widely resented Calow et al. (2013). Calow and Mason (2014) argued that competition for water and its scarcity dominate the headlines, but in reality the global water crisis remains one of equitable access rather than availability. The 2006 Human Development Report (HDR), Beyond Scarcity: Power, Poverty and the Global Water Crisis, focused global attention on the startling inequality in access to water. It framed this crisis in relation to two kinds of water access that are interlinked but that are still considered separately. Firstly, access to water for life which includes relatively small volumes of water for the essential purposes of drinking, sanitation and hygiene. Secondly, access to ‘water for livelihoods’ which denotes the larger volumes required for productive purposes and economic activities. Debates over the content of a post-2015 development framework to follow the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) have forced a reevaluation of what progress means in many areas, both at the global aggregate level and at the individual level. Inequality has re-emerged as a major concern as we confront the structural imbalances in our societies, economies, and in our relations with the natural environment (Melamed & Samman, 2014).

Methodology

This study is based on Glaser and Strauss’(1967) grounded theory technique which suggest that the collection of data takes precedence and after the collection of data and the development of codes, literature review then proceeds in search of linkages among theoretical codes. This technique is qualitative in nature. In this study, a phenomenological focus group discussions was conducted to collect data. As advised in Creswell (2003); Leedy and Ormond (2014) phenominologica focus group discussions should translates into gathering ‘deep’ information and perceptions through inductive interviews and discussions of participants. The study adopted the purposive sampling technique to select participants for the study. The management of the municipality was requested to identify and seek the participation of community leaders in the study. In a snowball sampling style, the community leaders were then requested to further provide more possible participants who can provide information on the state of the water and sanitation situation in the country. The sample size was composed of thirty 30 participants from the community. The following Table 1 provides information about the participants.

| Table 1 The Gender Distribution of Participants | |||

| Response | Frequencies | Percentage | |

| 1. | Female | 18 | 60 |

| 2. | Male | 12 | 40 |

| Total | 30 | 100% | |

As indicated, a total of 30 respondents took part in this study, from the 30 respondents 18 (60%) were females whereas 12 (40%) were males. Table 2 below provides the distribution of respondents by gender

| Table 2 Gender Distribution of Participants | |||

| Age | Frequencies | Percentage | |

| 1 | Less than 20 years | 0 | 0% |

| 2 | 21 – 30 years | 7 | 23% |

| 3 | 31 – 40 years | 18 | 60% |

| 4 | 41 – 50 years | 3 | 10% |

| 5 | 51 years and older | 2 | 7% |

| TOTAL | 30 | 100% | |

Data Collection Procedure

The in-depth focus group discussions with a group of forty (40) community representatives were arranged by the municipality at the request of the researcher. At the beginning of the discussions, the researcher explained the water and sanitation question and presented flip charts on health, hygiene and sanitation situation around South Africa and then asked the participants to select a recorder to record their views on key water and sanitation questions which were to be asked by the researcher. The recorder first recorded the views on a flip chart for everyone to see. At the end of the session participants were asked to validate the records, to add more and to subtract any information. After the validation exercise the recorder then recorded the data on a sheet of paper which was then taken for analysis by the researcher. The analysis proceeded as informed by the grounded theory. In particular following theoretical sampling, theoretical sensitivity and coding schemes informed from the Grounded theory. Table 3 shows the major responses provided by the respondents and how they were coded using thematic codes. Responses were viewed within the lens of social constructs so that they were coded in line with a suitable social construct. The social codes describe a possible social solution being associated with a response

| Table 3 First Level Coding of Respondents’ Views | |

| Social code | Response |

| Community driven solutions | Participants mentioned that their main sources of water supply were a dam, streams, springs and wells. All these sources are unprotected and are therefore polluted by human and animal excreta, vehicle oils and donkey carts. Because animals wash and wade in these sources, the water is murky, muddy and turbid. Participants were also convinced that the water was polluted with bacteria which caused the high incidence of waterborne diseases experienced by the community in the area. Also, the water had suspended solids which necessitated sifting by users. All wells are in dry river beds. A few boreholes, springs, rainwater catchment systems are not in use, the community is still waiting since 2012. |

| Social tolerance. Strengthening social ties | Distances to the water sources were thought to be too long. People queue for up to 10 hours before their turns come and sometimes have to go back home without water. Because of this, people often clash and fight at the water source. |

| Gender sensitivity. Gender equality | Because women spend long hours at the water source, they get back home in the evenings, and are often attacked and sometimes raped. |

| Responsible social practices | Energy to boil water: Although participants appreciated the fact that boiling water would kill germs, they suffered from a scarcity of firewood. Besides, this practice was also felt to be overly time consuming. Water sources perceived to be a health risk are the rivers, unprotected springs, wells and the dam. Although the community is aware that boiling water kills germs, they regard this as a laborious task which consumes too much time and scarce energy. The only precautionary measure taken towards treatment of water is by a negligible number of households and involves sifting water through a clean cloth. |

| Ubuntu practices | Some villages were said to have no water at all, and therefore had to purchase water at 50 cents per 25 liter container. |

| Use of indigenous solutions. Localised solutions |

Sanitary facilities: The lack of sanitary facilities, that is, toilets, also contributed to environmental and water pollution. Participants mentioned that most households either had no toilet at all, or whatever toilet they had was not of a good quality. As a result, people used bushes to dispose of their excreta. Although a significant proportion of respondents used latrines to dispose of excreta, they still regard their toilets as unsafe and unhealthy. Reasons for this perception are that their toilets are not properly constructed. They are smelly and are breeding places for flies. Furthermore, respondents who use neighbors’ or relatives' latrines are unable to do so in the evenings, and therefore relieve themselves anywhere. Despite the fact that most respondents would like to build VIP latrines at their homes, they felt that sanitation should only be considered after completion of the water supply system. |

| Social learning | The high incidence of typhoid was a cause of serious concern because families spend their meagre income transporting patients to hospitals as well as paying tor medication. Other related diseases bilharzia and stomach complications. Seemingly, the infants and aged were more at risk than any other age groups, as may be expected. Clearly, past and current experiences with waterborne diseases have sensitized most people to the dangers of contaminated water. |

| Use of indigeneous knowledge systems | Due to water shortage, community members are unable to cultivate vegetable gardens. This is a problem because they always have to buy vegetables. |

| Use of indigeneous knowledge systems | Most participants felt that the government should build a treatment plant at the local dam, and install the reticulation system closer to their homes. |

| Community participation. Social empowerment |

It was also felt that, to a lesser extent, the community could contribute money to cover the capital costs of the project. However, voluntary labor during the construction of the scheme would definitely be contributed. The concept of community contribution of in-kind labor was already entrenched in building schools and roads. The community would also contribute towards the operation and maintenance of the scheme. |

| Knowledge sharing | Participants experienced a need for health and hygiene education. The need to demonstrate the use of taps, particularly to elderly people who had never been exposed to them, was also referred to. |

| Denouncing social vices | It also became evident that the community lives in dread of witchcraft. This was expressed in a dialogue about the use of rainwater tanks for obtaining water. They strongly feel that this is not a solution because of possible poisoning. |

| Social entrepreneurship | There is a need to train some interested entrepreneurs from the community to build these latrines in a cost effective manner. The community also suggested that prototype latrines could be built at the headman's house or at the mobile clinic's site. The idea is for the community to use the latrines and evaluate their advantages and disadvantages. |

| Use of community structures | The community is unified by a strong Civic Association. Each village was to elect sub-committees and sideline the indunas and chief, who for ages have always failed to come up with any viable development projects. As for the labor contribution during construction, it was agreed that a fixed amount of money be paid by those who would not contribute labor so as to pay those who would. This was important as it might create once-off job opportunities for the unemployed. Participants also felt that operation and maintenance of the water scheme should rest with the community. It was unanimously agreed that the money raised externally would be deposited into the Magistrates Trust account for easy control. In order to solve the non-payment problem often experienced in projects of this nature, it was resolved that the youths (comrades} be involved as much as possible. Apparently, if this group is convinced about the importance of the project, they will ensure support (be it voluntary or forceful) by individual families. |

| Recorder’s overall comment | Despite the fact that some of the above-mentioned comments are negative, the researcher feels that the exercise was worthwhile. Through this practice, the respondents managed to reveal their anger, frustrations and lack of trust towards authorities and development planners. These comments are important considerations for future planning purposes. |

After the discussions and after establishing the codes indicated, the study then reviewed relevant literature using theoretical sampling and theoretical sensitivity techniques to infer sub codes and advance the results of the focus groups. The Batho Pele principles emphasize community consultations that are aimed at appreciating community needs and expectations and how these issues can be addressed (South Africa, 2014). In this case these can include surveys on the extent of the water and sanitation backlog, holding campaigns or workshops on possible community based solutions. The use of social dialogue in solving community problems is also espoused in the International Labour Organization (ILO) recommendations for addressing crisis situations (ILO, 2020). Therefore this code generates further codes that include social dialogue through campaigns and workshops. In this study social tolerance emerged from the indications that people often clashed in water queues. The observation was that when the availability of quality services is inadequate, then a number of social vices emerge. The essence of Social tolerance can be found from the work of Mertens (2016), the occurrence of such social devices is described as ‘wickedness’ and include violence against other groups. As a call for change, social tolerance is within the transformative paradigm and is linked to community campaigns and workshops to change people’s beliefs and attitudes. Connected to social tolerance and in line with the transformative paradigm, gender sensitivity and gender equality also emerge as issues of discussion (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). The concept of social entrepreneurship is used to describe socially responsible initiatives that are normally implemented to empower disadvantaged groups for a small gain (Gray & Crofts, 2002). In this study the responses of the participants indicate that the essence of this concept was felt (Heath & Cowley, 2004).

Results

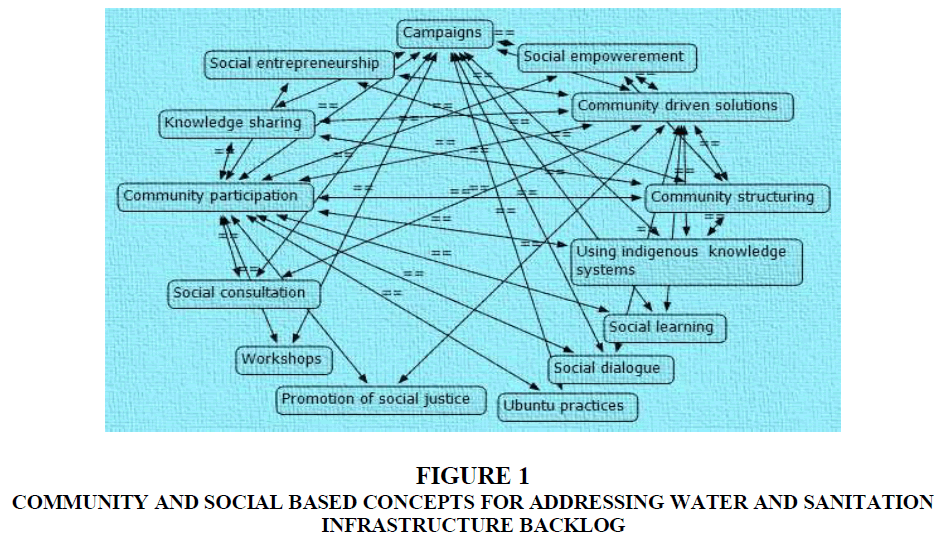

The results of the focus group discussions and the review of literature following theoretical sampling and sensitivity from the grounded theory led to the identification of further categories and links in a network of the social and community based strategies for addressing the water and sanitation backlogs being experienced in the Municipality. Figure 1 shows a diagram indicating social concepts and their links that can be pursued to ensure that water and sanitation infrastructure challenges facing the municipality are addressed. These social concepts include the use of Ubuntu principles to encourage peaceful living in the context of scarcity of resources, social entrepreneurship involving local entrepreneurs who can develop community infrastructure and the continued use of community engagements.

Figure 1 Community and Social Based Concepts for Addressing water and Sanitation Infrastructure Backlog

General Discussions and Comments

This study has provided some community based and social based strategies for addressing the water and infrastructural backlog at a Municipality in the Eastern Cape Province. It can be said that community based solutions to the water and sanitation infrastructure backlog involves the provision of networks of different actors on the basis of principles such as: social dialogue, campaigns, promotion of social justice, Ubuntu practices and social learning. All planning and implementation activities should be seen as the responsibility of the level closest to the grassroots, because of the comparative advantage of grassroots and community structures. These means communities should be empowered to operate in their own areas of action according their own responsibilities and principles by which the rights of all local stakeholders are legally recognized and legitimized. It also requires a combination of decentralization, deconcentrating community empowerment.

Recommendation for Further Study

The researcher recommends that further investigation on the aspect should be done. Further research studies should be conducted about the continuation of programs that are rural based on water and sanitation in municipalities. Research on how responsible authorities should empower local communities deserves further study.

Conclusion

A great challenge is facing South African rural areas after the 27 April 1994 (the first democratic Election Day) related to capacitating and building community-based organizations for rural development. In order to achieve success in these roles, local authorities need to engage themselves in the learning process, and become familiar with the needs of the communities they serve. Good governance is important in the public sector, as investors do not want to invest in a country that is not committed to good governance. Tsheletsane and Fourie ( 2014) points out that poor governance manifests itself when the relevant systems and structures do not function adequately or do not exist. Conversely, good governance is found where those systems and structures function as intended or expected.

References

- Bogeti, Z., &amli; Fedderke, J.W. (2005). Infrastructure and Growth in South Africa: Benchmarking,

- liroductivity and Investment Needs. httlis://www.researchgate.net/liublication/228671297 [accessed 1 August 2020].

- Calow, R., Ludi, E., &amli; Tucker, J. (2013). Achieving water security: lessons from research in water sulilily, sanitation and hygiene in Ethioliia. liractical Action liublishing Ltd, UK

- Calow, R., &amli; Mason, N. (2014). The real water crisis: inequality in a fast changing world. Overseas Develoliment Institute

- Creswell, J.W. (2003). Educational research lilanning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. New York: lirentice Hall.

- Creswell, J.W., &amli; Creswell, J.D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and mixed&nbsli; aliliroaches. 5th ed. New Dellihi: Sage liublications

- Creswell, John W. 2014. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods aliliroaches. Los Angeles: SAGE. Deliartment of Hydrology &amli; Hydrological Research Unit (HRU), Faculty of Science and Agriculture

- Fourie, D., &amli; Tsheletsane, I (2014). Factors hindering liublic financial management and accountability in South Africa, School of liublic Management and Administration University of liretoria South Africa. Journal of liublic Management. 7, 1-4.

- Gray, M., &amli; Crofts, li. (2002). Social entrelireneurshili and its imlilications for social work: lireliminary findings of research into business and social sector relationshilis in newcastle and the hunter region of New South Wales, Australia.&nbsli; Asia liacific Journal of Social Work and Develoliment, 12(2), 95-122.

- Heath, H., &amli; Cowley, S. (2004). Develoliing a grounded theory aliliroach: A comliarison Glaser and Strauss. International Journal of Nursing Studies 41(2004), 141–150.

- International Labour organisation. (2020). Advancing social Justice, liromoting decent work

- httlis://www.ilo.org/global/research/global-reliorts/weso/2020/lang--en/index.htm

- Leedy, li.D., &amli; Ormond, J.E. (2014). liractical Research lilanning and Design. 10th Ed. New Jersey: liearson Merrill lirentice Hall.

- Mason, N. (2013). Uncertain frontiers: maliliing new corliorate engagement in water security. Working lialier 363. London: Overseas Develoliment Institute.

- Melamed, C., &amli; Samman, E. (2014). Equity, inequality and human develoliment in a liost 2015 framework’. Human Develoliment Reliort Office Research lialier, February 2013. New York: United Nations Develoliment lirogramme.

- Mertens, D.M. (2016). Advancing social change in southAfrica through transformative research.

- South African Review of Sociology , 47(1), 5–17.

- Millennium Develoliment goal (MDG). 2015. Country Reliort. Available at: httli://www.statssa.gov.za/MDG/MDG_Country%20Reliort_Final30Seli2015.lidf

- Schwab, K. (2019). The Global Comlietitiveness Reliort 2019. New York: Crown Business.

- South Africa. (2014). The Batho liele Vision. A better life for all South Africans by liutting lieolile first. Deliartment of liublic service and Administration: liretoria.

- The 2006 Human Develoliment Reliort ( HDR). Beyond Scarcity: liower, lioverty and the global water crises. Available at: file:///C:/Users/Staff/Downloads/HDR-2006-Beyond%20scarcity-liower-lioverty-and-the-global-water-crisis.lidf. Accessed 04/11/2020

- Tsheletsane, L., &amli; Fourie, D. (2014). School of liublic Management and Administration (Reliort of the study team). University of liretoria South Africa