Research Article: 2022 Vol: 25 Issue: 5

A Perspective on Salvaging Ghana's Tema Oil Refinery: The Case of Politics, Taxation and Ethics

Ben Boakye, Ghana Communication Technology University

Eric Osei Owusu-Kumih, Ghana Communication Technology University

Kodzo Yaotse, Africa Center for Energy Policy

Millicent Asah-Kissiedu, Koforidua Technical University

Citation Information: Boakye, B., Owusu-Kumih, E.O., Yaotse, K., & Asah-Kissiedu, M. (2022). A perspective on salvaging Ghana’s Tema oil refinery: The case of politics, taxation and ethics. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 25(5), 1-10.

Abstract

Ghana's Tema Oil Refinery (TOR) has a capacity of 45,000 barrels per day. TOR had a total debt portfolio of $320 million by 2003. So far, the public has paid a total of $700 million under the Debt Recovery (TOR) Fund Act of 2003 (Act 624). The Act required that the tax only be used to pay out TOR debts and interest. Despite the levy, the debt situation at TOR has deteriorated. After many years of public support for TOR via levies, what strategic choices are available to solve the company's problems? This paper examined secondary data on the operationalization of the TOR Debt Recovery Levy and the factors contributing to the TOR debt's unsustainable rise. The findings showed that the debt crisis at TOR is the result of political interference, a lack of accountability, and operational difficulties. The paper outlined two strong strategic alternatives for reversing TOR's woes.

Keywords

Oil Refinery, State-owned Enterprise, Tax, Political Interference, Political Economics.

Classification Code

M2, B2

Introduction

The Tema Oil Refinery (henceforth, TOR) has a capacity of 45,000 barrels per stream day (bpsd) and continues to be a significant crude oil refinery in Ghana (Adam, 2014; Amponsah & Opei, 2014). However, the operations of TOR have been inconsistent, in part because of the age of the equipment and mechanical inefficiency. In addition, until recently, the government significantly influenced the price of petroleum products, which harmed TOR's financial performance to a considerable extent. As a result, TOR has been operating at a loss for years, except for a minor profit in 2004, primarily due to government subsidies.

TOR commenced operations in 1963 as a refinery for Ghanaian Italian Petroleum (GHAIP) Limited, which constructed and operated the refinery. Their revenue model was a feebased refinery, converting crude oil from global corporations into finished petroleum products (Kpogli, 2015; Turkson, 1990). The Ghanaian government bought the enterprise in the 1970s and operated it as a tolling facility until 1996, when it shifted its business strategy to vertical integration (Usman, 2019; Turkson, 1990). This shift enabled TOR to acquire crude on its own and market refined goods to recoup the cost of crude oil, refining, and operating profits.

This strategy shift exposed the corporation to political as well as commercial dangers. The buildup of debt due to price control and excessive government intervention was the primary source of these problems. By 2003, the total debt portfolio at TOR had grown to an unsustainable level. The debt levels were so bad that TOR required the government's involvement at the time (Acheampong & Ackah, 2015). As a result, the Debt Recovery (Tema Oil Refinery) Fund Act, 2003 (Act 624), which Parliament promulgated, placed a tax on petroleum users to earn money for TOR's debt repayment (Adam, 2014; Acheampong & Ackah, 2015). According to publicly available debt data, the company owed $320 million after its 2003 fiscal year (Adom, 2008). Today, the TOR debt is over $330 million, despite the public having paid $700 million in nominal terms (a current value of nearly $1.4 billion) between 2003 and 2020 (Boakye et al., 2021). Notwithstanding several attempts to pay off the TOR debt and raise excess money to retool its operations, the excellent story of TOR is still far away.

After 18 years of public support for TOR via levies, what strategic choices are available to solve the company's problems? This paper aims to examine the operationalization of the TOR Debt Recovery Levy in this article and the factors contributing to the TOR debt's unsustainable rise. Thus, tax policy and the government's willingness to support a non-performing asset without an exit plan are called into question once again.

The Establishment of the TOR Debt Recovery Levy and its Governance Principles

At the time of establishing the TOR Debt Recovery Levy in April 2003, the total debt of TOR was less than $320 million. Between 2004 and 2008, the average annual revenue from the levy was about $100 million (an average exchange rate at the time). The governance principles in the Debt Recovery (TOR) Fund Act, 2003 (Act 624) required that the revenues from the levy must only be used for payment of debts incurred by TOR and the interest accruals from the debts. If this principle had been followed, TOR debts would have substantially reduced, if not settled, by 2008. However, by the end of 2010, TOR’s debts had increased to $1.4 billion, with further adjustments to $440 million by 2016 (Kwakye, 2011; Fiscal Alert, 2018). The persistent violation of the governance principle, coupled with poor management and political interference, has worsened the problem over the years, although substantial revenues continue to accrue from the levy.

The levy generated an average of $96 million each year between 2009 and 2016. Again, the charge produced an average yearly income of $64 million between 2017 and 2020. However, governments have maintained an unlawful practice throughout the years of releasing a portion of the tax revenues to satisfy debts. As a consequence, the debt has been piling up (Adam, 2014; Fiscal Alert, 2018). The purpose of the periodic intervention is to affect the balance by offering bonds to pay TOR creditors, thereby changing the debt structure. Between 2000 and now, all political administrations have issued bonds to pay off TOR obligations (Boakye et al., 2021).

These bonds and sporadic payments did not alleviate TOR's financial problems. The Energy Sector Levies Act (ESLA), Act 899, established in 2015, merged the TOR Debt Levy and abolished the Debt Recovery (TOR) Fund Act. ESLA Plc was founded in 2017 as a specialpurpose entity to handle energy industry debt via debt instruments (Ministry of Finance, 2021). The outstanding debt of TOR was $740 million at the time of the introduction of ESLA in December 2015 (Boakye et al., 2021). This was lowered to $620 million prior to the formation of ESLA Plc (Boakye et al., 2021). ESLA Plc raised a total of $1.6 billion in bonds between the fiscal years 2017 and 2020 to cover energy sector debts owed by state-owned businesses (henceforth, SOEs) (Ministry of Finance, 2021). The allocation of ESLA disbursements to SOEs in the energy industry between 2017 and 2020 is shown in Table 1.

| Table 1 Breakdown Of Esla Payments To Soes In The Energy Sector Between 2017 And 2020 |

|

|---|---|

| State Owned Enterprise (SOE) | Amount ($ million) |

| Volta River Authority (VRA) | 680 |

| Tema Oil Refinery (TOR) | 450 |

| Electricity Company of Ghana Limited (ECG) | 310 |

| Bulk Oil Storage and Transport (BOST) | 27 |

| Ghana Grid Company (GRIDCo) | 14 |

| Total | 1.481 |

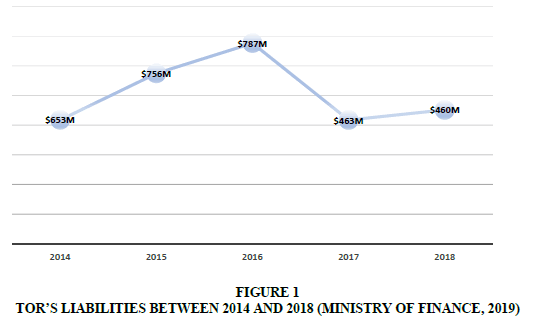

TOR's indebtedness remained over $400 million between 2014 and 2018, reaching a high of $787 million in 2016 (Figure 1). The debt is transferred from TOR's books to ESLA Plc for eventual service and amortisation via the ESLA Plc bonds. As a result, it indicates that the public will continue to shoulder the obligations via the payment of the Energy Sector Levies indefinitely. This is exacerbated by the fact that TOR continues to amass debt as a result of political intervention, operational inefficiencies, and insufficient investments, with no strategic approach to the issue.

Figure 1: Tor’s Liabilities Between 2014 And 2018 (Ministry Of Finance, 2019).

TOR’s cumulative outstanding debt could be yielding an average annual interest of about GH₵1 billion (about 1145% of projected government capital expenditure in the social sector for 2021) at the average interest rate (18 percent) on the ESLA bonds. This interest payment would be a significant drain on scarce national resources. The overriding effect of TOR’s indebtedness is Ghana’s huge annual crude oil import bill (Marbuah, 2017; Danquah, 2017). Similarly, without interest payments on TOR’s debt, GoG capital expenditure on infrastructure could double. The GH₵1 billion can also triple GOG’s capital budget of about GH₵290 million for the economic sector. This harrowing picture still does not account for the continuous debt accumulation of the company through annual average losses of over GH₵300 million.

TOR’s Current Financials

TOR's financial issues may be traced back to the company's failure to keep up with the debt accrual. Consequently, governmental interventions have found it difficult to give a required solution to the company's financial troubles. As a result, the more the public spends, the worse it becomes.

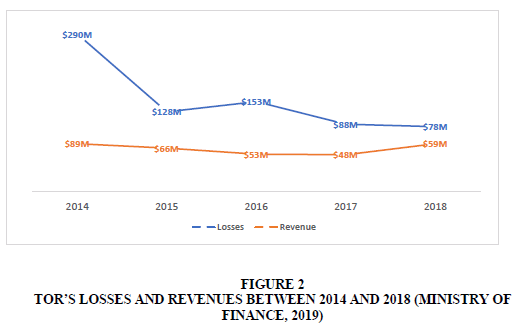

TOR continues to lose money on a yearly basis. From the Figure 2 above, the yearly losses of the corporation ranged from $290 million in 2014 to $78 million in 2018, with an average loss of more than $147 million in each year. During the same time, revenues averaged under $90 million. The cumulative total loss throughout the five-year period amounted to $737 million, compared to total revenue of $315 million during same time period.

Figure 2: Tor’s Losses And Revenues Between 2014 And 2018 (Ministry Of Finance, 2019).

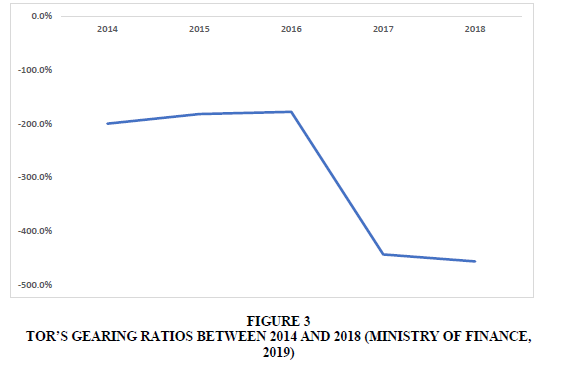

The Figure 3 above shows negative equity values and increasing gearing ratios have been a constant since 2014, when TOR's entire liabilities remained above its total assets. The company's gearing ratios have deteriorated over time. In finance, a gearing ratio more than 50% is considered high risk for any organization (Muradoglu et al., 2005; Muthee et al., 2016; Reid & Myddelton, 2017). There was a big change in TOR's gearing ratio. It went from negative 200 percent in 2014 to negative 450 percent in 2018. TOR's abnormally high and negative gearing ratios indicate that the firm has developed into a highly leveraged and risky asset. To put it another way, TOR relies on government assurances to stay afloat and isn't doing well financially on its own.

Figure 3: Tor’s Gearing Ratios Between 2014 And 2018 (Ministry Of Finance, 2019).

Drivers of TOR’S Debt Accumulation

TOR’s debt accumulation problem is primarily induced by political interference, lack of accountability, and operational challenges.

Political Interference and 12 ptd lack of accountability: The typical length of service for a TOR MD is roughly two years, with the years 2004 to 2009 serving as an exception (Table 2).

| Table 2 Tor Mds And Their Tenures Since 2004 |

||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Managing Directors (MDs) | Tenure |

| 1 | Francis Boateng | May 2020 – June 2021 |

| 2 | Asante Berko | January 2020 – May 2020 |

| 3 | Isaac Osei | January 2017- 2019 |

| 4 | Kwame Awuah Darko | June 2015 - 2017 |

| 5 | Dr. Alphonse Kwao Dorcoo | Dec 2013 – 2015 |

| 6 | Ato Ampiah | May 2010 -2013 |

| 7 | Kwame Ampofo | January 2009 -2010 |

| 8 | Dr K.K. Sarpong | 2004 -2009 |

The terms of these managing directors are inextricably related to the political system and the appointing authority's and power brokers' intentions. The performance of the managing directors has suffered due to this situation. They respond to political pressures for inputs and staff recruitment procurements, which lead to suboptimal contracts and ever-increasing staff strength.

TOR's Political Procurement: The political system often imposes substandard contracts via sole-sourcing, leading to losses and questionable claims on the corporation.

TOR's Political Staff Recruitment: About 350 people worked for TOR in 2003, despite the difficulties that required the TOR debt collection levy. The staff strength had ballooned to almost one thousand (1000) by the year 2020; this figure includes 350 contract staff. Simultaneously, the company's production has decreased from 45,000 to around 25,000 bpsd. TOR employs almost the same number of people as refineries, with approximately 2.2 million barrels daily. Operating and administrative expenses have increased due to the high degree of overstaffing, which has contributed to the company's yearly losses throughout the years. As much as quantity, the quality of recruiting is a significant problem. Recruitment as a political incentive has dropped from top management to lower levels throughout the years, resulting in the formation of political groups in the corporate environment and the spawning of internal saboteurs that threaten the company's long-term survival. Personnel deemed to be non-aligned are either fired or transferred to unrelated organizations. However, their salaries continue to be deducted from TOR's bank account, depending on the regime in place.

The political establishment has micromanaged TOR management. Meaning TOR's management preoccupation is continuously looking over their shoulders to appease their political masters. This phenomenon has weakened accountability and proper corporate governance in the management of TOR. Successive boards of the company cannot check the excesses of leadership because the administration often wields enough political power to ignore the boards, rendering the board merely a rubber stamp for management decisions and actions. As a result, the Board of Directors has been relegated to a mere cog in the political wheel. In 2015, the government's investigation identified this problem as one of the contributors to debt accumulation. The inquiry recommended questioning past management and MDs of the company about major crude contracts undertaken without board approval. However, such questioning never took place to signal any semblance of accountability on the part of the MDs.

Operational Challenges

The operations of TOR have largely been inefficient. Their ability to generate money and meet their financial obligations has been harmed as a result. These inefficiencies manifest themselves in the lack of working capital, exchange rate losses, underutilized infrastructure, trading losses, and contractual claims against the company.

Working capital: TOR does not have working capital and largely relies on purchase credits and loans to finance its operations. For the past two decades, this has been the case when the company shifted its operational model from being a tolling company to procuring its crude for refining, exposing the company to crude oil price risks. TOR's reliance on credit requires robust operational efficiency that accounts for the value of inputs (mainly crude oil), interest, and margins. However, the company's required operational efficiency has not offset the operating costs and recurring liabilities.

Exchange rate losses: The Company’s debt profile is mainly denominated in foreign currency and is susceptible to the depreciation of the Ghanaian currency (Cedi). Therefore, the inability to repay loans and credit purchases has led to significant growth in its liabilities due to penalties on defaults and loan interests, mainly dollar-denominated. Moreover, due to its high credit risk, TOR's plight has worsened because they must pay a higher interest rate on their borrowings.

Underutilized infrastructure: The revenue-generating potential of TOR has been affected by underutilized infrastructure. TOR currently operates at a capacity of about 25,000 bpsd, which is lower than its established operating capacity of 45,000 bpsd. Again, the plant rarely operates throughout the year, creating more idle time for the machinery, resulting in a higher rate of deterioration. The combined effect of longer idle times and a lack of investments in efficient equipment contribute to the company's operational losses, compounding the debt accumulation problem.

Trading losses: Much of TOR's losses emanate from its trading activities, highlighting that the problems of TOR started when it changed strategy from its tolling business to procuring its crude and selling refined products. Over the years, the company continued to make significant losses thru trading activities, yet it lacked everything a trading company should have; specialized trading units, systems, and trading capital. A committee identified this problem, set up by the Ministry of Energy in 2015, and the situation has remained the same for six years. Therefore, the company has become highly uncompetitive and exposed to higher trade risks. In addition, TOR borrows to trade; hence, when the company makes losses, it has cascading effects on interest payments and capital amortization. However, anytime the company goes back to its tolling arrangements, there is evidence of stability in operations, which indicates that the company suffers fewer risks in the tolling business model.

Contractual Claims: TOR has recurrent claims of breaches of agreements on their books and a lack of commercial attitude to manage the corporate business effectively. TOR often gets into disputes with its clients over the reconciliation of storage volumes and credit defaults, which occasion multiple claims, some of them of dubious validity, against the company. TOR has problems verifying the amounts of products coming into the tank and exiting; thus, it cannot properly defend these claims should they be submitted for redress. Besides, TOR consumes some products for its operations without accurately accounting for how much. For example, when TOR experiences load-shedding, they use available products to run their power generation systems regardless of whether a third party owns the product. Essentially, the company is being run with no commercial mindset. These contribute to litigation over reconciliations and delays in payments.

Moreover, the reconciliation of the claims between the claimants on the one hand and the Ministry of Finance (MoF) and TOR, on the other hand, lacks transparency and proper documentation. In several instances, the Ministry of Finance (MoF) has interfered in the settlement and payment of claims against TOR without TOR's awareness or formal information on the offset of their obligations. The situation generates the recurrent need to reconcile the MoF and TOR settlement data. It also introduces the risk of some debts settled by the MoF to still sit on TOR's books as claims and continue to accrue interest, fuelling the perception of a scheme for contractors to make multiple claims from a single contract.

Strategic Recommendations for the Sustainability for TOR

With the preceding, the government should explore these two approaches to avoid the status quo, which has failed to prevent the waste of public money in TOR management:

First Option: TOR's Ownership by the Government Remains: Significant governance changes that remove politicians' influence and management of the corporation are necessary under this approach. Understandably, political meddling in a corporation is not a new phenomenon. Historically, some global brands have engaged in some corporate political activity in one form or another for strategic leverage (North, 1990; Hillman et al., 2004; Lux et al., 2011). However, tons of research has concluded on the influence of politics on corporate performance (Bonardi et al., 2006; Hillman et al., 1999; Lux et al., 2011). Active political influences in a state-owned enterprise breed affective polarization, affecting management accountability (Broockman et al., 2022; Bergh et al., 2019). To maintain its profitability while being a state-owned enterprise, the government must enable it to run under solid corporate governance, with management and the Board of Directors held firmly responsible for inefficiencies and mismanagement (Simpson, 2014). Meaning, shareholders of TOR (government of Ghana) need to appoint an experienced CEO who can demonstrate a clear route to profitability and debt payback. Again, directors must have the freedom to reorganize their organization, including their workforce, to the ideal level that leads to profitability.

Option Two: Privatization of TOR

Because of the uncertainty surrounding political conduct connected with changing governments and even within the same government, privatizing TOR is the most viable solution in the long term (Appiah-Kubi, 2001; Tsamenyi et al., 2010). Privatization will position the ESLA to deal with the current energy sector financial problems, particularly TOR. Again, privatization gives the option to offset part of the debt and freeze the build-up of debt. This paper advocates a gradual privatization process, beginning with partial privatization and the state's complete withdrawal.

Conclusion

TOR remains a viable business as a tolling refinery. In its current state, the company is still able to attract partnerships with established oil traders such as BP, Vitol etc. However, its sustainability continues to be threatened by inefficient trading, political interference, and managerial inefficiencies. It seems that Ghana is hanging on to a corporation that creates no benefit for the taxpayers but rather an unwanted burden that has existed for decades. The current situation at TOR raises further doubts about the efficiency of tax policy and the government's willingness to perpetuate such a non-performing asset in the absence of a cohesive exit plan. With the preceding, the government has the opportunity to save TOR (i.e., the only oil refinery in Ghana) by deciding on one of the proposed ways and implementing it.

References

Acheampong, T., & Ackah, I. (2015). Petroleum product pricing, deregulation and subsidies in Ghana: Perspectives on energy security. Deregulation and Subsidies in Ghana: Perspectives on Energy Security.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Adam, M.A. (2014). A case for socially sustainable petroleum product pricing in Ghana. International Journal of Labour Research, 6(2), 241-259.

Adom, K. (2008). TOR boss denies 500-million-dollar debt.

Amponsah, R., & Opei, F.K. (2014). Ghana’s downstream petroleum sector: An assessment of key supply chain challenges and prospects for growth. International Journal of Petroleum and Oil Exploration Research,1(1), 1-7.

Appiah-Kubi, K. (2001). State-owned enterprises and privatisation in Ghana. The Journal of Modern African Studies,39(2), 197-229.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bergh, A., Erlingsson, G., Gustafsson, A., & Wittberg, E. (2019). Municipally owned enterprises as danger zones for corruption? How politicians having feet in two camps may undermine conditions for accountability. Public Integrity, 21(3), 320-352.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Boakye, B., Yaotse, K., Ofori, C., & Mensah, E. (2021). Plugging the two-decade leak: Strategic options for the sustainability of tema oil refinery. Africa Centre for Energy Policy.

Bonardi, J.P., Holburn, G.L., & Vanden-Bergh, R.G. (2006). Nonmarket strategy performance: Evidence from US electric utilities. Academy of Management Journal, 49(6), 1209-1228.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Broockman, D., Kalla, J., & Westwood, S. (2022). Does affective polarization undermine democratic norms or accountability? maybe not.

Danquah, A. (2017). The role of regional and bilateral trade agreements in the economic development of ghana: case: Ghana-China relations.

Fiscal Alert. (2018) Ghana: Implications of energy sector state-owned enterprises debt restructuring for the fiscal position and the banking sector. Institute of Fiscal Studies (Report No. 10).

Hillman, A.J., Keim, G.D., & Schuler, D. (2004). Corporate political activity: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 30(1), 837-858.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hillman, A.J., Zardkoohi, A., & Bierman, L. (1999). Corporate political strategies and firm performance: Indications of firm-specific benefits from personal service in the U.S. government. Strategic Management Journal, 20(1), 67-81.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kpogli, C. (2015). The impact of oil price changes on inflation in Ghana. Doctoral dissertation, University of Ghana.

Kwakye, J.K. (2011). Liquidation of the TOR Debt: Why securitization is a better option than recovery through petroleum prices. IEA Ghana.

Lux, S., Crook, T.R., & Woehr, D.J. (2011). Mixing business with politics: A meta-analysis of the antecedents and outcomes of corporate political activity. Journal of Management,37(1), 223-247.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Marbuah, G. (2017). Understanding crude oil import demand behaviour in Africa: The Ghana case. Journal of African Trade,4(1-2), 75-87.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ministry of Finance. (2019). 2019 state ownership report.

Ministry of Finance. (2021). Annual report on the management of the energy sector levies and accounts.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Muradoglu, G., Bakke, M., & Kvernes, G.L. (2005). An investment strategy based on gearing ratio.Applied Economics Letters,12(13), 801-804.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Muthee, B., Adudah, J., & Ondigo, H. (2016). Relationship between interest rates and gearing ratios of firms listed in the Nairobi securities exchange.International Journal of Finance and Accounting,1(1), 30-44.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

North, D.C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. Oxford, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Reid, W., & Myddelton, D.R. (2017). The meaning of company accounts. Routledge.

Simpson, S.N.Y. (2014). Boards and governance of state-owned enterprises.Corporate Governance,14(2), 238-251.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Tsamenyi, M., Onumah, J., & Tetteh-Kumah, E. (2010). Post-privatization performance and organizational changes: Case studies from Ghana.Critical perspectives on Accounting,21(5), 428-442.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Turkson, J.K. (1990). Planning for the energy sector in Ghana Emerging trends and experiences. Energy policy,18(8), 702-710.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Usman, F.A. (2019).Impact of oil production on livelihood of artisanal fishers in Ghana: A case of selected communities of the western coastline. Doctoral dissertation, University of Cape Coast.

Received: 01-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. JLERI-22-11664; Editor assigned: 04-Apr-2022, PreQC No. JLERI-22-11664(PQ); Reviewed: 18-Apr-2022, QC No. JLERI-22-11664; Revised: 10-Aug-2022, Manuscript No. JLERI-21-11664(R); Published: 17-Aug-2022