Research Article: 2023 Vol: 26 Issue: 6

A modified Model of the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem to Foster the Launching of Start−ups in Iranian Universities

Zohreh Motamedi Nia, Ilam University

Maryam Azizi, Ilam University

Hossein Mahdizadeh, Ilam University

Citation Information: Nia, Z.M., Azizi, M., & Mahdizadeh, H. (2023). A modified model of the entrepreneurial ecosystem to foster the launching of start-ups in iranian universities. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 26(6),1-16.

Abstract

This research attempts to provide a modified model of the entrepreneurial ecosystem to foster the launching of start-ups in Iranian universities. This study was conducted using a sequential mixed approach (qualitative-quantitative). The findings showed that the important components for launching start-ups in universities were respectively as follows: human capital, culture, support, market, policy and financial capital in the modified model of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. However, the availability of the components was assessed to be low to medium. It is therefore recommended that universities’ mission be adjusted according to the cycle of entrepreneurship and university majors be redefined according the needs of the labour market.

Keywords

Entrepreneurial Ecosystem, Iranian Universities, Launching of Start-ups, Isenberg's model, Modified Model.

Introduction

The unemployment of university students and graduates and limited entrepreneurship among them has become one of the fundamental challenges in societies. Therefore, universities must become more deeply involved in promoting entrepreneurship. The participation of universities in entrepreneurship based on regional and national factors can significantly contribute to the promotion of entrepreneurship and create the necessary structures for entrepreneurial activities. Universities should play a dynamic role in the entrepreneurial ecosystem and engage in cultural and socio-economic growth. The most outstanding universities across the world are established with entrepreneurship in mind and their academic and research programs are designed according to the characteristics of the regional entrepreneurial ecosystem such as infrastructures, resources, human capital, and culture, leading to dynamism and regional growth (Brush, 2014). Despite the practical necessity of including entrepreneurship in universities’ mission statements, the development of university-level entrepreneurship still faces some deficits in Iran; if ignored, these deficits will contribute to the country's underdevelopment. Persisting with outdated quantitative indicators such as the number of institutions, majors, and graduates fails to offer solutions and might exacerbate the current conditions. Therefore, it is necessary to comprehensively analyse entrepreneurship and its foundations in Iranian universities and develop a system with the aim of achieving the goals of entrepreneurship.

Despite the existing understanding of entrepreneurship and its importance in many countries, especially in developing countries such as Iran, the topic has not been approached systematically and most treatments approach the concept with a limited scope, instead of a systemic approach. Thus, an Eco systemic approach that takes into account the intertwined relationships of the elements in the ecosystem must be adopted. The entrepreneurial ecosystem approach has emerged as a basis for designing entrepreneurial policies. Considering Iran's socioeconomic conditions (e.g., rapid expansion of higher education, large growth in the number of science and technology parks and incubators, sanctions against the country, etc.), this study seeks to achieve the following goals:

a) Identifying and presenting a modified model of the entrepreneurial ecosystem to foster the launching of startups in Iran’s higher education system.

b) Evaluating the availability of the entrepreneurial ecosystem to foster the launching of start-ups in Iran’s higher education system.

Theoretical Foundations

Entrepreneurial Ecosystem and Universities

Many experts view entrepreneurship as a prerequisite for development (Chiru et al., 2012; Davey et al., 2016; Robinson & Shumar, 2014). Entrepreneurship has also been proposed as a method for overcoming contemporary socioeconomic challenges (Bruton et al., 2013; Sutter et al., 2019). Consequently, many governments have come to regard the entrepreneurial ecosystem as the cornerstone of their policy and have taken measures to foster knowledge-based entrepreneurship. However, there are no universal solutions for creating the entrepreneurial ecosystem and therefore academics are still exploring the topic through theoretical and empirical studies (Wurth et al., 2021).

Despite the gaps in our understanding of how the entrepreneurial ecosystem forms and functions, institutions of higher learning are often among the core components of these ecosystems (Isenberg, 2010), and these institutions have been identified as one of the most important drivers of entrepreneurship (Muscio & Ramaciotti, 2019; Saeed et al., 2015; Turker & Selcuk, 2009). Given these, entrepreneurship has been included among the missions of universities along with education and research and has been given a higher priority than the other two (Czarnitzki, 2016). In an entrepreneurial ecosystem, universities are regarded as the most substantial institutes; therefore, significant research attention has been paid to the role of universities as centres of entrepreneurial activity (Kingma, 2014; Rice et al., 2014; O'Connor & Reed, 2015; Fernandez Fernandez et al., 2015; Schaeffer & Matt, 2016).

Universities have employed various approaches to fulfil their role in economic development, including the provision of financial benefits through the dissemination of knowledge (O’Gorman et al., 2008; Wood, 2011; Acs et al., 2013), technology transfer (university entrepreneurship) (O’Gorman et al., 2008; Wood, 2011) and cultivation of entrepreneur students in university entrepreneurship programs (Maritz et al., 2016). The role of universities in economic development has been well recognized by governments, researchers and policy makers Dennis (2011); Wells (2012); O'Neal & Schoen (2013) and policies at different levels reflect this fact (Smith, 2007; Sandstrom et al., 2018). The role of universities in the entrepreneurial ecosystem is especially prominent in bringing together entrepreneurial actors and institutions, exchanging information, and creating a fertile socio-economic environment for entrepreneurship (Audretsch & Belitski, 2017).

Although the concept of the entrepreneurial ecosystem is relatively new, researchers have taken up the subject in a number of studies. In a study of six universities in four countries, Rice et al. (2014) found that a minimum of 20 years is needed for all components of the entrepreneurial ecosystem to come together at a university. Baraldi & Havenvid (2016) report their findings on how a university incubator forms and develops in a global and regional context. Fu & Hsia (2017) studied the entrepreneurial ecosystem at Stanford University and found that the ecosystem is created at the confluence of a culture of risk taking, a community oriented towards entrepreneurship, government support, collaboration with the industry, and high-quality human resources. Miller & Acs (2017) employed Turner’s boundary theory to study the entrepreneurial ecosystem at Chicago University and found the following to be the main factors contributing to the formation of the ecosystem: academic agency, diversity of the human resources, and availability of assets and facilities. Thomsen et al. (2018) point to resource allocation for entrepreneurship, increased attention to entrepreneurship, and incentivization of students as the major factors supporting entrepreneurship at universities.

Although some attention has been paid to entrepreneurship in Iranian universities, the attempts have often been disjointed and superficial. For instance, at some universities, entrepreneurship is approached only through offering elective courses, while at others, entrepreneurship centres, incubators, and science and technology parks have been established. In contrast, the University of Tehran has established an independent college of entrepreneurship. These actions have been taken while universities are still struggling to improve the conditions of their graduates as potential entrepreneurs. This could be due to the lack of sufficient attention to entrepreneurship as a strategic goal at universities and the failure of universities to understand the subject and its components and approach them with an operational plan. Therefore, the current research attempts to provide a modified model of the entrepreneurial ecosystem based on the Isenberg’s model in order to study the entrepreneurial ecosystem at Iranian universities and foster the launching of start-ups in universities.

Entrepreneurial Ecosystem

The entrepreneurial ecosystem entered academic literature in the 1980s and 1990s as attention shifted from individualistic approaches towards community-oriented perspectives that integrate the environment in which entrepreneurship takes place (Nijkamp 2003; Steyaert & Katz 2004). Although the popularity of this approach has been on the rise, there is still no clear definition for the entrepreneurial ecosystem (Stam & van de Ven, 2021). Stam (2015) defines the entrepreneurial ecosystem at a regional level as the collection of actors and factors working together to make productive entrepreneurship possible. Mason & Brown (2014) define the concept as the set of actors (both potential and existing), organizations (e.g. banks and venture capitalists), institutions (e.g., universities and governmental agencies), and processes (serial entrepreneurship, level of ambition) that come together to form and maintain the local entrepreneurial environment. According to Nicotra et al. (2018), the entrepreneurial ecosystem is the collection of social, political, economic, and cultural components at a regional scale that foster the formation and growth of innovative start-ups and encourage individuals to engage in entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial activities.

The characteristics of environments which foster entrepreneurship have also been formulated by various organizations such the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the World Economic Forum (WEF), and the World Bank. For instance, OECD defines the environmental components of the entrepreneurial ecosystem as the theoretical foundations, market conditions, availability of capital, R&D and technology, entrepreneurial potential, and culture. Asset Mapping Roadmap proposes eight factors which affect entrepreneurship including human resources, research institutions, capital, industrial infrastructure, and organizations involved in entrepreneurship, policy environment, infrastructure, and quality of life (Nicotra et al., 2018).

Daniel Isenberg, a professor at Babson College, has proposed a comprehensive model of the entrepreneurial ecosystem which includes six domains. This model will be explored in greater detail in the following sections.

Isenberg’s Model of the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem

The concept of an entrepreneurial ecosystem was developed to promote economic development through fostering entrepreneurship, innovation, and the growth of small businesses (Mazzarol, 2014). In this approach, it is assumed that elements such as policy, financial capital, market, culture, human capital, and the necessary supports are in place for the formation and self-sustaining existence of an entrepreneurial ecosystem (Isenberg, 2011).

The policy domain includes two main elements (i.e., government and leadership). A functioning entrepreneurial ecosystem persuades politicians to support entrepreneurship and entrepreneurs and to eliminate the obstacles faced by entrepreneurs. Human capital covers labour and educational institutions, which provide the human resources for the entrepreneurial ecosystem. The entrepreneurial ecosystem relies on individuals with sufficient knowledge and experience to kick start the ecosystem and guide its growth and development. In this regard, it is crucial that universities equip students with the skills and experience needed for entrepreneurial activity (e.g., financial literacy) and allow their faculty to participate in entrepreneurship through offering incentives for engaging with entrepreneurship and liaising with non-academic entities. Elements of financial infrastructure such as private equity and venture capital funds constitute the third dimension of Isenberg’s model and contribute to the ecosystem by providing the necessary supports for taking risks and launching start-ups. The entrepreneurial ecosystem also relies on the availability of markets, which can be seen as a collection of customers and networks. The cultural dimension covers the prevailing attitudes in the society towards entrepreneurship and the history of entrepreneurial activities. These can range from the availability of narratives of successful entrepreneurship to the public perceptions of entrepreneurial activities, especially among the youth. Support from non-governmental entities and the availability of infrastructure and the necessary professional personnel represent the sixth dimension of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Non-governmental entities allow entrepreneurs to create international networks and infrastructure to satisfy the fundamental needs of businesses such as transportation and communication. The support dimension also encompasses the availability of professionals such as accountants and marketing strategists who are flexible in terms of working arrangements and remuneration.

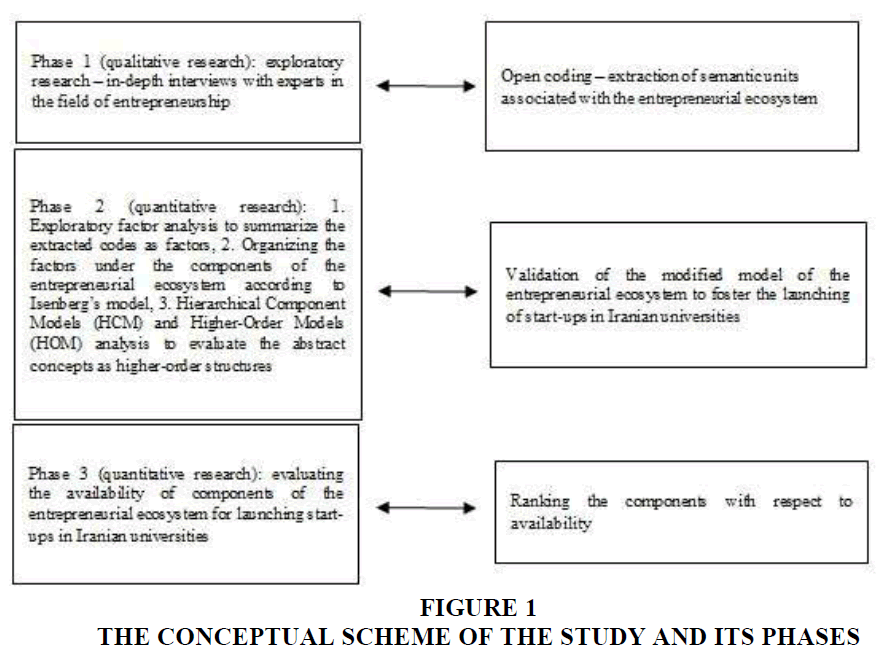

Given the favourable perception of Isenberg’s model among policy makers (Stam & Spigel, 2016) and its wide-spread adoption (Malecki, 2018), a modified version of Isenberg’s model for fostering entrepreneurship in Iranian universities was developed by extracting the semantic units associated with the entrepreneurial ecosystem, summarizing the units as factors, and categorizing the factors according to Isenberg’s model. A schematic representation of the research process is presented in Figure 1.

Research Design and Context

The current research utilizes a sequential mixed approach (qualitative-quantitative) in three phases, as shown in Figure 1. First, in-depth interviews with experts in the field of entrepreneurship (experts, authorities, university professors, and managers of successful businesses) were used to explore the dimensions of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. In this phase, the semantic units (codes) associated with the entrepreneurial ecosystem were extracted. In the quantitative phase, the extracted codes were first summarized as factors, followed by categorization under the components of Isenberg’s model. In the third phase, entrepreneurial actors were surveyed to evaluate the availability of components of the entrepreneurial ecosystem for launching start-ups in Iranian universities.

Phase 1: Exploratory Qualitative Research

This phase was undertaken to perform a qualitative in-depth study of the opinions of key experts in the field of entrepreneurship regarding the conditions of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Iranian universities. To this aim, semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted with 21 key experts until theoretical saturation was reached. The interviews were then analysed using a content analysis approach through extracting the semantic units associated with the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Semantic units included words, sentences, or paragraphs which conveyed concepts associated with aspects of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. To analyse the content of the interviews, four coders extracted the semantic units; in cases of disagreement, joint sessions were held to ensure the validity and reliability of the semantic units through triangulation.

The geographical differences in the entrepreneurial ecosystem lead to differences in entrepreneurial opportunities and mind sets. As a result, to extract the codes associated with the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Iranian universities, we conducted in-depth interviews with key experts in the field using open questions. This phase started by soliciting the general perspectives of the experts regarding entrepreneurial ecosystems. The experts were aged 32-59 and interviews were conducted in person at their place of work or on the phone. The duration of the interviews ranged from 45 minutes to 2 hours and 10 minutes. The interviewees independently answered similar questions. The interviews were recorded and transcribed immediately after each interview. Semantic units were identified and extracted using MAXQDA12.

Phase 2: Quantitative Research

In the second phase of the study, the 71 semantic units extracted in the qualitative phase were summarised into 22 factors using exploratory factor analysis in SPSS 24. The identified factors were cross-referenced with Isenberg’s model of the entrepreneurial ecosystem and categorized under its components. The factors identified in the modified model were also validated using Hierarchical Component Models (HCM) and Higher-Order Models (HOM) analysis in Smart-PLS3.

Phase 3: Quantitative research

In the third phase of the study, the availability of the components of entrepreneurial ecosystem models was evaluated for launching start-ups in Iranian universities.

Quantitative Sample

The statistical population for the quantitative section of the study included 1800 entrepreneurial actors in Iran (start-up founders and managers). Cochran’s formula was used to determine the sample size. Of the 310 structured online questionnaires distributed among the study population, 24 were excluded due to incomplete information and the remaining 286 were used for the analyses. The online questionnaire was prepared using Avalform and distributed using email and social media (Avalform is an Iranian platform for the creation and distribution of online questionnaires).

The questionnaire collected demographic information and the perceptions of entrepreneurial actors regarding the availability of the entrepreneurial ecosystem for launching start-ups in Iranian universities.

Prior to data collection, an informed consent form covering the detailed goals of the research and confidentiality was provided to the respondents. The respondents were asked to express their perceptions of the availability of entrepreneurial ecosystems for launching start-ups in Iranian universities on a five-point Likert scale (1=very low, 5=very high).

Results

Demographic Characteristics

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the study sample. Among the entrepreneurial actors, 70.3% were men and 55.9% were aged 31-40. With respect to educational background, 55.9% of the respondents had a master’s degree and 58.7% had studied management and social sciences.

| Table 1 Demographic Characteristic of the Entrepreneurial Actors | |||

| Variable | Levels | Frequency | Percentage |

| Gender | Female | 85 | 29.7 |

| Male | 201 | 70.3 | |

| Age | 21-30 | 88 | 30.8 |

| 31-40 | 160 | 55.9 | |

| 41-50 | 32 | 11.2 | |

| 51-60 | 6 | 2.1 | |

| Education | Bachelor’s | 57 | 19.9 |

| Master’s | 160 | 55.9 | |

| PhD | 69 | 24.2 | |

| Field of education | Management and social sciences | 168 | 58.7 |

| Engineering | 83 | 29 | |

| Agriculture | 24 | 8.4 | |

| Basic sciences | 11 | 3.8 | |

Reliability and validity of the Research Instrument

Table 2 presents the mean, Cronbach’s alpha, validity and reliability for the components of the entrepreneurial ecosystem.

| Table 2 Mean, Cronbach’s Alpha, Validity and Reliability on the Components of the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem | |||||||

| Constructs | Mean | SD | Variance | α | CR | θ | AVE |

| Policy | 2.52 | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.65 |

| Culture | 2.83 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.72 |

| Human capital | 2.83 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.74 | 0.83 | 0.76 | 0.56 |

| Support | 2.71 | 0.81 | 0.67 | 0.76 | 0.86 | 0.77 | 0.68 |

| Market | 2.57 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.63 |

| Financial capital | 2.55 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.75 | 0.89 | 0.77 | 0.80 |

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) is a data reduction technique used to extract a small number of underlying factors from a larger set of corresponding items using factor rotation (Hair, 2010; Wismeijer, 2012). In this study, the semantic units (i.e., extracted codes) associated with the entrepreneurial ecosystem were summarised using EFA.

EFA was performed through principal component analysis using varimax rotation (Yong & Pearce, 2013). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure (KMO=0.85) showed that the sample size had been adequate for performing EFA. Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p < 0.001) indicated that inter-item correlation was strong enough for analysis of factor structure (Yong & Pearce, 2013). The factors were evaluated using factor and cross-loading criteria, and those with a loading lower than 0.5 were sequentially excluded from the analysis (Field, 2017). Of the 71 extracted codes, two did not have loadings > 0.5 on any of the factors (i.e., clustering of start-ups and model localization at universities).

As shown in Table 3, EFA produced a 22-factor model with 69 codes explaining 69.67% of total variance, which is higher than the acceptable level in social sciences. The 22 factors were named according to their constituent codes. Table 3 presents the factors and the extracted codes.

| Table 3 The Identified Factors, Semantic Units, Factor Loadings, Along with their Means and Standard Deviations | ||||

| Factor | Semantic unit (code) | Factor loading | Mean | SD |

| Strengthening the private sector | Support for the formation of venture capital in the private sector | 0.82 | 2.67 | 0.96 |

| Incentivizing the private sector to enter the entrepreneurial ecosystem | 0.64 | |||

| Delegation of activities in the entrepreneurial ecosystem to the private sector | 0.62 | |||

| Authority designation | Designation of authorities for the entrepreneurial ecosystem | 0.78 | 2.50 | 0.94 |

| Unified and centralized policy making for the entrepreneurial ecosystem | 0.69 | |||

| Clarification and disambiguation of laws regarding the entrepreneurial ecosystem | 0.67 | |||

| Development of strategies and roadmaps for the entrepreneurial ecosystem | 0.59 | |||

| Productive entrepreneurship | Increasing the risk for unproductive investments | 0.74 | 2.63 | 0.96 |

| Support for productive start-ups | 0.72 | |||

| Defining regional indices for start-ups | 0.69 | |||

| Balanced development | Legislation for balanced development in the country | 0.78 | 2.27 | 0.97 |

| Preventing the accumulation of capital in the centre of the country | 0.71 | |||

| Preventing concentration of entrepreneurial activity in the centre of the country | 0.58 | |||

| Governmental incentive programs | Setting appropriate tax rates for productive businesses | 0.73 | 2.43 | 0.95 |

| Reducing the costs of launching start-ups | 0.58 | |||

| Reducing the bureaucratic requirements for launching start-ups | 0.53 | |||

| Successful role models | The role of local successful role models | 0.79 | 3.11 | 0.98 |

| The role of national successful role models | 0.79 | |||

| Dissemination of success stories | 0.71 | |||

| Culture of entrepreneurship | Development of a culture of entrepreneurship among university students | 0.78 | 2.75 | 0.97 |

| Development of a culture of entrepreneurship among faculty members | 0.78 | |||

| The role of education in the development of a culture of entrepreneurship at universities | 0.76 | |||

| Entrepreneurial mind set | Enhancing the entrepreneurial mind set at universities | 0.83 | 2.63 | 0.96 |

| Enhancing the competitive mind set at universities | 0.73 | |||

| Enhancing the systemic mind set at universities | 0.67 | |||

| Availability of consultants | Availability of company registration consultants at universities | 0.88 | 2.63 | 0.96 |

| Availability of legal consultants at universities | 0.86 | |||

| Availability of taxation consultants at universities | 0.72 | |||

| Provision of physical space | Provision of physical space for start-ups by universities | 0.84 | 3.01 | 0.95 |

| Provision of physical space for start-ups by the responsible organizations | 0.80 | |||

| Provision of physical space for start-ups by large corporations | 0.65 | |||

| Provision of infrastructure | Availability of legal infrastructure at universities | 0.85 | 2.90 | 0.96 |

| Availability of taxation infrastructure at universities | 0.76 | |||

| Availability of socio-cultural infrastructure at universities | 0.59 | |||

| Supporting organizations | Establishment of entrepreneurship, technology transfer, and industrial liaison offices at universities | 0.87 | 2.74 | 0.98 |

| Establishment of incubators and innovation centres at universities | 0.78 | |||

| Collaboration between universities and accelerators | 0.69 | |||

| Networking | Formation of a local network of entrepreneurs | 0.86 | 2.60 | 0.97 |

| Formation of a national network of entrepreneurs | 0.80 | |||

| Formation of an international network of entrepreneurs | 0.75 | |||

| Creation of a competitive environment | Attention to competitiveness at universities | 0.80 | 2.35 | 0.98 |

| Attention to import substitution at universities | 0.78 | |||

| Attention to value chains at universities | 0.58 | |||

| Attention to political conditions | Attention to the political conditions of the country | 0.86 | 2.75 | 0.96 |

| Attention to the country’s international relations | 0.84 | |||

| Attention to the country’s currency value | 0.74 | |||

| Teaching of entrepreneurship skills | Teaching financial literacy at universities | 0.88 | 2.93 | 0.94 |

| Teaching marketing skills at universities | 0.86 | |||

| Teaching management skills at universities | 0.86 | |||

| Teaching team building skills at universities | 0.79 | |||

| Teaching ideation at universities | 0.76 | |||

| Policy making for higher education | Modification of universities’ mission according to the cycle of entrepreneurship | 0.82 | 3.04 | 0.91 |

| Defining university majors according to the needs of the labour market | 0.80 | |||

| Revision of the syllabi offered at universities | 0.71 | |||

| Encouragement of students | Offering experimental education for developing students’ entrepreneurial skills | 0.84 | 2.82 | 0.92 |

| Holding educational workshops for developing students’ entrepreneurial skills | 0.80 | |||

| Holding events for developing students’ entrepreneurial skills | 0.72 | |||

| Encouragement of faculty members | Offering suitable benefits to faculty members for entrepreneurial activities | 0.86 | 2.63 | 0.95 |

| Revision of university bylaws related to the promotion of faculty members | 0.69 | |||

| Familiarization of faculty members with launching start-ups and the concept of entrepreneurship | 0.62 | |||

| Budget targeting at universities | Allocation of grants to commercialized research by faculty members | 0.79 | 2.68 | 0.94 |

| Allocation of suitable budget for commercialization of the academic research output | 0.77 | |||

| Impartial allocation of university budget | 0.74 | |||

| Access to financial resources | Access to financial resources through governmental banks | 0.87 | 2.50 | 0.95 |

| Access to financial resources through private banks | 0.86 | |||

| Access to financial resources through venture capitalists | 0.81 | |||

| Timely capital injection | Timely injection of governmental capital to start-ups | 0.91 | 2.27 | 0.92 |

| Timely injection of private capital to start-ups | 0.83 | |||

| Access by start-ups to seed capital for growth | 0.67 | |||

| KMO value | 0.85 | |||

| Barlett’s test | 0.000 | |||

| Total variance explained | 69.67% | |||

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

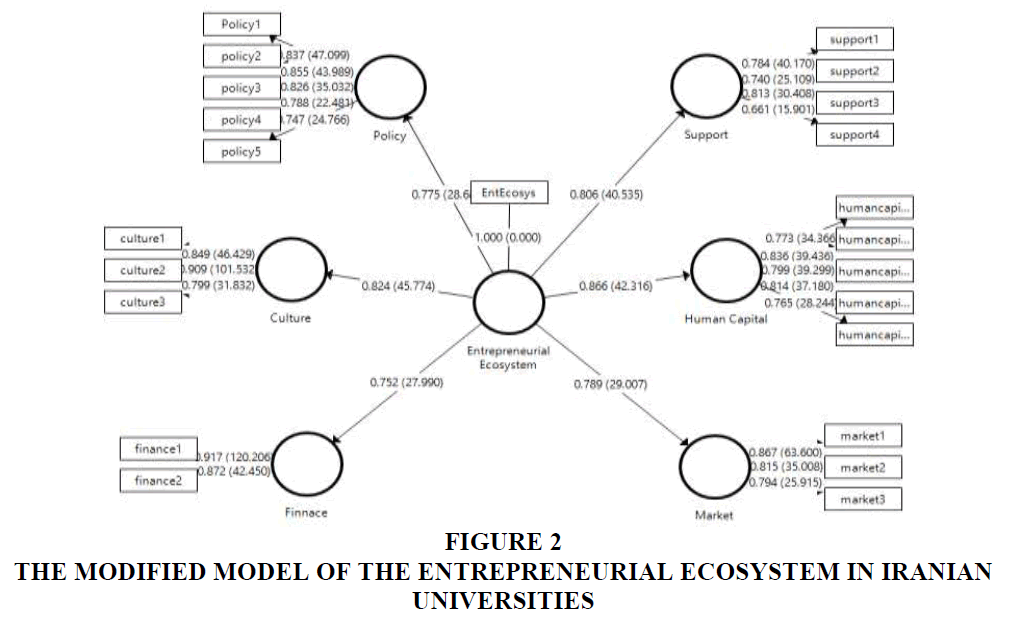

In this section, a hierarchical component model and a second-order model are presented to evaluate the modified model of the entrepreneurial ecosystem for launching start-ups in universities. Hierarchical component models and higher-order models often include two layers of abstracted components. Hierarchical measurement can be extended to as many layers as needed, but researchers often employ two layers in this approach and regard the use of more than two layers as a limitation.

Composite Reliability (CR)

The composite reliability of the latent variables exceeded the critical threshold of 70% (Table 2). Cronbach’s alpha varied from 74% to 87%. The results indicate that the latent variable is reliable and the constructs have high reliability and internal consistency.

Convergent Validity

As seen in Table 2, the constructs had average variance extracted (AVE) values > 0.5, confirming the convergent validity of the latent variables.

Construct Validity

Table 4 presents the factor loadings for the indicators under each construct. The significance of the indicators (P>0.01) shows that the indicators possess the required importance for measurement. The validity of the constructs confirms that indicators are suitable factor structures for studying the dimensions in the research model.

| Table 4 Factor Loadings for the Indicators Under each Construct in the Measurement Model | |||||

| Construct | Factors | Indicator | Factor Loading | t | Sig |

| Policy | Authority designation | Policy 2 | 0.85 | 43.98 | 0.000 |

| Strengthening the private sector | Policy 1 | 0.83 | 47.09 | 0.000 | |

| Productive entrepreneurship | Policy 3 | 0.82 | 35.03 | 0.000 | |

| Balanced development | Policy 4 | 0.78 | 22.48 | 0.000 | |

| Governmental incentive programs | Policy 5 | 0.74 | 24.76 | 0.000 | |

| Culture | Culture of entrepreneurship | Culture 2 | 0.90 | 101.53 | 0.000 |

| Successful role models | Culture 1 | 0.84 | 46.42 | 0.000 | |

| Entrepreneurial mind set | Culture 3 | 0.79 | 31.83 | 0.000 | |

| Support | Provision of infrastructure | Support 3 | 0.81 | 30.40 | 0.000 |

| Availability of consultants | Support 1 | 0.78 | 40.17 | 0.000 | |

| Provision of physical space | Support 2 | 0.74 | 25.10 | 0.000 | |

| Supporting organizations | Support 4 | 0.66 | 15.90 | 0.000 | |

| Human capital | Policy making for higher education | Human capital 2 | 0.83 | 39.43 | 0.000 |

| Encouragement of faculty members | Human capital 4 | 0.81 | 37.18 | 0.000 | |

| Encouragement of students | Human capital 3 | 0.79 | 39.29 | 0.000 | |

| Teaching of entrepreneurship skills | Human capital 1 | 0.77 | 34.36 | 0.000 | |

| Budget targeting at universities | Human capital 5 | 0.76 | 28.24 | 0.000 | |

| Market | Networking | Market 1 | 0.86 | 63.60 | 0.000 |

| Creation of a competitive environment | Market 2 | 0.81 | 35.008 | 0.000 | |

| Attention to political conditions | Market 3 | 0.79 | 25.91 | 0.000 | |

| Financial capital | Access to financial resources | Finance 1 | 0.91 | 120.20 | 0.000 |

| Timely capital injection | Finance 2 | 0.87 | 42.45 | 0.000 | |

Discriminant validity

We assessed discriminant validity (i.e., divergent validity) along with the validity of the constructs, which is used to evaluate the importance of the indicators for the measurement of constructs. The indicators under each construct should ultimately provide suitable discriminatory power relative to the other constructs. In simpler terms, each indicator should only measure the construct it belongs to and the combination of the indicators should adequately discriminate the constructs. Discriminant validity was evaluated using the square root of AVE as all constructs had AVE > 0.4. Moreover, the square root of AVE for any construct the diagonal in Table 5 is larger than the correlation of other constructs with that construct. This criterion is also known as the Fornell-Larcker criterion.

| Table 5 Comparison of the Square Root of ave with the Correlations BETWEEN Constructs (Fornell-Larcker Criterion) | ||||||

| Construct | Construct | Construct | Construct | Construct | Construct | Construct |

| Culture | 0.85 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Financial capital | 0.47 | 0.89 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Human capital | 0.68 | 0.55 | 0.79 | --- | --- | --- |

| Market | 0.57 | 0.65 | 0.58 | 0.82 | --- | --- |

| Policy | 0.66 | 0.48 | 0.59 | 0.49 | 0.81 | --- |

| Support | 0.57 | 0.52 | 0.72 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.75 |

Structural Model of the Study

The structural model of the study was created using the hierarchical components models and the higher-order models (Figure 2). The components of the modified model of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Iranian universities were ranked as follows with respect to importance: 1- human capital (β=0.86, t=42.31), 2- culture (β=0.82, t=45.77), 3-support (β=0.80, t=40.53), 4- market (β=0.78, t=29.007), 5- policy (β=0.77, t=28.60), 6- financial capital (β=0.75, t=27.99).

Ranking the Components of the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem

The perceptions of entrepreneurial actors with respect to the availability of the components of the entrepreneurial ecosystem ranged from low to medium. Human capital and culture had the largest means on the five-point Likert scale (mean=2.83, SD=0.94 and mean=2.83, SD=0.91, respectively). The policy components had the smallest mean (mean = 2.52, SD = 0.81).

Discussion

Today, the unemployment of university students and graduates has become one of the fundamental challenges faced by higher education systems. The best way to solve this problem is to train efficient and creative individuals and prepare students and graduates for employment in the labour market by moving towards entrepreneurial development. Therefore, universities have dedicated significant attention to entrepreneurship and have made it a priority. Many experts also emphasize the importance of universities and their role in the development of knowledge-based economies. They believe that institutionalization and development of entrepreneurship in higher education centres can solve the employment crisis among students and graduates and promote self-employment. Along with education and research, universities have made entrepreneurship their third mission with the hope of creating and promoting an entrepreneurial environment.

In recent years, Iranian universities have taken steps towards the promotion of entrepreneurship, although the attempts so far have not been able to generate the necessary motivation among students and graduates to enter the world of entrepreneurship. Given the importance of educational environments, particularly higher education, in creating connections between students and graduates and entrepreneurship, universities should take steps towards developing an entrepreneurial environment and take on new responsibilities in this field. Taking an ecosystem approach to this task can be helpful.

Entrepreneurial ecosystems can be defined at various levels, from the university level to the national level (Fetters et al., 2010; Morris et al., 2017), which means university ecosystems are connected to the regional ecosystems as well as the internal elements in the university ecosystem (Isenberg, 2010; WEF, 2014; Miller & Acs, 2017). Internally, universities can foster the development of the entrepreneurial ecosystem by creating a fertile educational environment, adopting a supportive management approach, and providing the necessary infrastructure for entrepreneurship (Miller & Acs, 2017). Several universities have invested large sums of money towards this goal (Sieger et al., 2014).

Conclusion

The goal of this study was to provide a modified model of the entrepreneurial ecosystem to foster the launching of start-ups in Iranian universities. The main findings of the study are as follows:

First Phase of the Study

In the first phase (qualitative research), 71 codes associated with the entrepreneurial ecosystem were extracted from in-depth semi-structured interviews with key experts in the field of entrepreneurship.

Second Phase of the Study

In the second phase, 286 entrepreneurial actors were surveyed. Among the respondents, 70.3% were men. Women constitute more than half of Iran’s college-educated population. However, the majority of founders and managers at Iranian start-ups are men, which indicates the male atmosphere of the business and start-up spaces in Iran. The results also showed that 55.9% of start-up founders and managers were aged 31-40, 55.9% had a master’s degree, and 58.7% held management or social science degrees.

In the second phase, exploratory factor analysis was used to summarise the codes extracted in the qualitative phase, resulting in 22 factors. The identified factors were then crossreferenced with Isenberg’s model of the entrepreneurial ecosystem and were categorized under the model’s components. Next, the identified factors were validated. Hierarchical components models and higher-order models showed that human capital ranked first in the modified model of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. The factors within this component were ranked as follows: policy making for higher education, encouragement of faculty members, encouragement of students, teaching of entrepreneurship skills, and budget targeting at universities.

The culture component ranked second in the modified model, and its constituent factors were ranked as follows: culture of entrepreneurship, successful role models, and entrepreneurial mind set. The support component ranked third. “Provision of infrastructure” was the most important factor under this component, followed by availability of consultants, provision of physical space, and supporting organizations. The market component was ranked fourth in the modified model and its factors were ranked as follows: networking, creation of a competitive environment, and attention to political conditions. The fifth component in the modified model with respect to importance was policy, whose factors were ranked as follows: authority designation, strengthening the private sector, productive entrepreneurship, balanced development, and governmental incentive programs. Financial capital was the least important component in the modified model and the factors under this component were ranked as follows: access to financial resources, followed by timely capital injection.

In the modified model, access to financial resources and supporting organizations had the largest and smallest factor loadings for the formation of start-ups in Iranian universities, respectively, highlighting the importance of access to financial resources for launching start-ups. This finding also indicated that the organizations tasked with supporting entrepreneurship have not been successful in motivating university students and graduates to launch start-ups in Iranian universities.

Third Phase of the Study

The third phase of the study evaluated the availability of the components of the entrepreneurial ecosystem from the perspective of entrepreneurial actors. The results showed that entrepreneurial actors had low to medium perceptions of the availability of the components. In other words, the actors did not believe that the components were easily available in Iran. In terms of availability, human capital and culture were ranked the highest, which means the factors that compose these components have the largest contribution to creating a suitable environment for launching start-ups in Iranian universities (the factors include policy making for higher education, encouragement of faculty members, encouragement of students, teaching of entrepreneurship skills, budget targeting at universities, culture of entrepreneurship, successful role models, and entrepreneurial mind set). The policy component had the smallest mean, meaning the factors falling under this component have not made significant contributions to creating an environment that is suitable for launching start-ups (the factors include authority designation, strengthening the private sector, productive entrepreneurship, balanced development, and governmental incentive programs).

Given the findings of this study, the following recommendations are made to stimulate the formation of start-ups in Iranian universities: Based on the importance of making new policies in higher education (under the human capital component in the model), universities’ mission statements should be adjusted according to the cycle of entrepreneurship, majors should be revised according to the needs of the labour market, and syllabi should be re-evaluated to create the necessary conditions for the formation of start-ups by university students and graduates.

Limitations

The limitations of this study include the difficulty of finding the target population’s phone numbers (to make calls and find individuals on social media), the difficulty of finding the respondents’ email addresses, failure to receive responses in a timely manner, the need for reminders, and the need to send the online questionnaire multiple times.

References

Acs, Z.J., Audretsch, D.B. & Lehmann, E.E. (2013). The knowledge spill over theory of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 41 (4), 757–774.

Audretsch, D.B. & Belitski, M. (2017). Entrepreneurial ecosystems in cities: establishing the framework conditions. Journal of Technology Transfer, 42 (5), 1030–1051.

Baraldi, E., & Havenvid, M.I. (2016). Identifying new dimensions of business incubation: A multi-level analysis of Karolinska Institute's incubation system. Technovation, 50, 53-68.

Brush, G. (2014). Exploring the Concept of an Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystem Innovative Pathways for University Entrepreneurship in the 21st Century. Advances in the Study of Entrepreneurship. Innovation & Economic Growth, 24 (1), 25-39.

Bruton, G.D., Ketchen, D.J. & Ireland, R.D. (2013). Entrepreneurship as a solution to poverty. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(6), pp. 683-689.

Chiru, C., Tachiciu, L. & Ciuchete, S.G. (2012). Psychological factors, behavioral variables and acquired competencies in entrepreneurship education. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 4010-4015.

Czarnitzki, D., Doherr, T., Hussinger, K., Schliessler, P. & Toole, A.A. (2016). Knowledge creates markets: the influence of entrepreneurial support and patent rights on academic entrepreneurship. ZEW Discussion Papers, 16-036, 1-45.

Davey, T., Rossano, S. & van der Sijde, P. (2016). Does context matter in academic entrepreneurship? The role of barriers and drivers in the regional and national context. Journal of Technology Transfer, 41(6), 1457-1482.

Dennis W.J. (2011). Entrepreneurship, small business and public policy levers. Journal of Small Business Management, 49 (1), 92-106.

Fernandez Fernandez, M.T., Blanco Jimenez, F.J. & Cuadrado Roura, J.R. (2015). Business incubation: Innovative services in an entrepreneurship ecosystem. Service Industries Journal, 35 (4), pp. 783- 800.

Fetters, M., Greene, P.G., & Rice, M.P. (2010). The development of university-based entrepreneurship ecosystems: Global practices. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Field, A. (2017). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (North American edition). SAGE Publications.

Fu, E., & Hsia, T. (2014). Universities and entrepreneurial ecosystems: Elements of the Stanford-Silicon Valley success. Kauffman Fellows Report, 5, 2014.

Hair, J., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. & Gudergan, S. (2010). Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling, Sage, Thousand Oak.

Isenberg, D.J. (2010). The big idea: How to start an entrepreneurial revolution. Harvard Business Review 12.

Isenberg, D.J. (2011). The entrepreneurship ecosystem strategy as a new paradigm for economic policy: principles for cultivating entrepreneurship.

Kingma, B. (2014). Creating a dynamic campus–community entrepreneurial ecosystem: Key characteristics of success. In Academic entrepreneurship: Creating an entrepreneurial ecosystem, 97-114.

Malecki, E.J. (2018). Entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial ecosystems. Geography compass, 12(3), e12359.

Maritz, A., Koch, A. & Schmidt, M. (2016). The role of entrepreneurship education programs in national systems of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship ecosystems. International Journal of Organizational Innovation, 8 (4), 7–27.

Mason, C. & Brown, R. (2014). Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Growth Oriented Entrepreneurship. Final Report to OECD, 30 (1), 77-102.

Mazzarol, T. (2014). Growing and sustaining entrepreneurial ecosystems: what they are and the role of government policy, White Paper WP01-2014. Small Enterprise Association of Australia and New Zealand (SEAANZ).

Miller, D.J. & Acs Z.J. (2017). The campus as entrepreneurial ecosystem: The University of Chicago. Small Business Economics. 49 (1), 75-95.

Morris, Mh.H., Shirokova, G. & Tsukanova T. (2017). Student entrepreneurship and the university ecosystem: a multi-country empirical exploration. European Journal of International Management, 11 (1), 65-85.

Muscio, A., & Ramaciotti, L. (2019). How does academia influence Ph. D. entrepreneurship? New insights on the entrepreneurial university. Technovation, 82, 16-24.

Nicotra, M., Romano, M., Giudice, M. & Schillaci, C.E. (2018). The causal relation between entrelireneurial ecosystem and liroductive entrelireneurshili: A measurement framework. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 43 (3), 640-673.

Nijkamp, P. (2003). Entrepreneurship in a modern network economy. Regional Studies, 37 (4), 395–405.

O’Gorman, C., Byrne, O. & Pandya, D. (2008). How scientists commercialise new knowledge via entrepreneurship. Journal of Technology Transfer, 33 (1), 23–43.

O’Neal, T., & Schoen, H. (2013). Universities’ role as catalysts for venture creation. In Academic Entrepreneurship and Technological Innovation: A Business Management Perspective, 153-181.

O'Connor, A., & Reed, G. (2015). Promoting regional entrepreneurship ecosystems: The role of the university sector in Australia. In Australian Centre for Entrepreneurship Research Exchange Conference 2015, 772-788.

Rice, M.P., Fetters, M.L. & Green, P.G. (2014). University- based entrepreneurship ecosystem: a global study of six educational institutions. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 18 (5/6), 481-501.

Robinson, S. & Shumar, W. (2014). Ethnographic evaluation of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A methodological conceptualization. International Journal of Management Education, 12, 422-432.

Saeed, S., Yousafzai, S. Y., Yani-De-Soriano, M. & Muffatto, M. (2015). The role of perceived university support in the formation of students’ entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Small Business Management, 53 (4), 1127-1145.

Sandström, C., Wennberg, K., Wallin, M.W., & Zherlygina, Y. (2018). Public policy for academic entrepreneurship initiatives: a review and critical discussion. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 43(5), 1232-1256.

Schaeffer, V. & Matt, M. (2016). Development of academic entrepreneurship in a non-mature context: The role of the university as a hub-organization. Entrepreneurship and regional Development, 28 (9-10), 724- 745.

Sieger, P., Fueglistaller, U. & Zellweger, T. (2014). Student entrepreneurship across the globe: a look at intentions and activities.

Smith H.L. (2007). Universities, innovation, and territorial development: a review of the evidence. Environ Plan C Govern, 25 (1), 98–114.

Stam, E. & Spigel, B. (2016). Entrepreneurial Ecosystems, In Blackburn, R., De Clercq, D., Heinonen, J. and Wang, Z. (E.ds). Handbook for Entrepreneurship and Small Business. London, UK: Sage.

Stam, E. (2015). Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Regional Policy: a sympathetic critique. European Planning Studies, 23 (9), pp. 1759–1769.

Stam, E., & van de Ven, A. (2021). Entrepreneurial ecosystem elements. Small Business Economics, 56, 809–832.

Steyaert, C. & Katz, J. (2004). Reclaiming the space of entrepreneurship in society: geographical, discursive and social dimensions. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 16 (3), 179–196.

Sutter, C., Bruton, G. D. & Chen, J. (2019). Entrepreneurship as a solution to extreme poverty: A review and future research directions. Journal of Business Venturing, 34 (1), 197-214.

Thomsen, B., Muurlink, O. & Best, T. (2018). The political ecology of university-based social entrepreneurship ecosystems. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 12 (2), 199-219.

Turker, D. & Selcuk, S. S. (2009). Which factors affect entrepreneurial intention of university students?. Journal of European Industrial Training, 33 (2), 142-159.

WEF. (2014). Entrepreneurial Ecosystems around the Globe and Early-Stage Company Growth Dynamics.

Wells, J. (2012). The role of universities in technology entrepreneurship. Technology Innovation Management Review, 24, 35-40.

Wismeijer, A.A.J. (2012). Dimensionality analysis of the thought suppression inventory: Combining EFA, MSA, and CFA. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 34 (1), 116–125.

Wood, M.S.A. (2011). Process model of academic entrepreneurship. Business Horizons, 54 (2), 153–161.

Wurth, B., Stam, E. & Spigel, B. (2021). Toward and Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Research Program. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice.

Yong, A.G. & Pearce, S. (2013). A beginner’s guide to factor analysis: Focusing on exploratory factor analysis tutorials in quantitative methods for psychology. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 9 (2), 79–94.

Received: 04-Spe-2023, Manuscript No. AJEE-23-13964; Editor assigned: 06-Sep-2023, Pre QC No. AJEE-23-13964(PQ); Reviewed: 20- Sep -2023, QC No. AJEE-23-13964; Published:27-Sep-2023