Research Article: 2017 Vol: 21 Issue: 2

A Critical Review of Organizational Identification: Introducing Identity Work to Examine Dynamic Process

Yusuke Tsuchiya, Kobe University

Keywords

Organizational Identification, Identity Work, Career Paths, Career Choices.

Introduction

For many people, managing their careers has become increasingly difficult. Due to massive corporate downsizing, frequent career changes and increased cultural and demographic diversity in recent years, there has been a shift away from long-term relational contracts in favour of shorter-term transactional alternatives (Albert, Ashforth & Dutton, 2000). Career research uses broadly theoretical lenses to examine how individuals cope with these changing environments and manage their careers.

OID research provides one such theoretical explanation vis-à-vis organizational careers and boundary-less careers. OID research examines “a psychological bond” (Riketta & Van Dick, 2005) between an individual’s identity and organizational identity. This is important in order to understand why some people remain employed by the same organization.

In response to the dynamics of individual career paths, career research suggests that careers without boundaries are an important conception (Authur, 1994). In the same way, OID research has also explored the separation between individuals’ identities and organizational identities. In the context of boundary-less careers it is important to understand and explain why some people want to leave particular organizations and change careers.

Career research has paid more attention to the process of career change in recent years (Khapova, Arthur, Wilderom & Svensson, 2007; LaPointe, 2010). However, OID research needs to explore people’s OID processes: It is not sufficient to suggest only theoretical explanations (Pratt, 1998). Moreover, Miscenko & Day (2016) suggest that future OID research “should critically examine the assumption that OID is stable” (p. 231). Therefore, we need to consider problematizing OID. Why has not and why cannot OID research explore people’s OID processes? This study concludes that this disjoint has been created and maintained because OID research tends to view people’s OID processes as socially deterministic.

The purpose of this paper is to review theoretically and critically OID research and to justify why the concept of identity work is useful and important to overcome problems and limitations with OID framings. As such, this review discusses: (1) The essence of organizational identification; (2) problems with organizational identification; (3) how identity work overcomes OID problems; (4) problems with identity work and (5) future research directions vis-à-vis career paths and career choices.

Critical Review Of Organizational Identification Research

The Essence of Organizational Identification

Glimmers of the construct now known as OID appear very early in the organization research. For example, Ashforth, Harrison & Corley (2008) cited Chester Barnard, Frederick Taylor & Herbert Simon. However, the construct gained traction and became more main stream over the last 20 years.

OID research was re-conceptualized by Ashforth & Mael (1989) who applied social identity theory (SIT) in an organizational context. OID is “the degree to which a member defines him or herself by the same attributes that he or she believes define the organization” according to a well-known definition by Dutton, Dukerich & Harquail (1994). First, how do you explain people’s identification processes and preferences using SIT?

SIT is based on the assumption that people are motivated toward self-enhancement. The self-enhancement motive means that people are motivated to enhance self-esteem (Hogg & Abrams, 1988). People discriminate on the basis of in-group versus out-group by social categorization and social comparison to enhance their self-esteem and thus people can identify groups or categories pursuant of that objective (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). Social categorization means that people categorize themselves in a specific social group or social category. For example, “I am a student at Kobe University.” Whereas social comparison means that people evaluate social groups or social categories which they join as higher than those which they do not join (Hogg & Abrams, 1988). For example, “I am proud to be a student at Kobe University; I hold it in higher regard than Tokyo University.”

Based on SIT, OID research mainly examined the determining factor. For example Edwards & Peccei (2010); He, Pham, Baruch & Zhu (2014) examined that perceive organizational support (POS) enhanced OID. Similarly, Hameed, Riaz, Arain & Farooq (2016) examined that external corporate social responsibility (CSR) and external CSR enhanced OID. Moreover, recent research examined moderate/mediated mechanism of OID. For example, Callea, Urbini & Chirumbolo (2016) examined that the effect of job insecurity on organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) and job performance was completely mediated by OID.

Additionally, previous OID research tabled a new concept, dis-identification (Dukerich, Kramer & Mclean-Parks, 1998). Dis-identification means that people cannot discriminate in-group from out-group by social categorization and social comparison to enhance their self-esteem and thus, people try to segregate that groups or categories.

Understandably, previous OID research findings have implications for career research. Such research provides theoretical justification for organization-oriented careers because they are sustained, at least partly, through OID; and dis-identification can explain boundary-less careers. In sum, if people evaluate organizational identity positively, pursuing and adhering to organizational identity can enhance their self-esteem and, as a result, people choose organizational careers. Whereas if people do not evaluate organizational identity positively or are not confident in their abilities to evaluate organizational identity at all, it is not useful to enhancing their self-esteem, thus people dis-identify with organizational identity and, as a result, choose boundary-less careers.

The Problem of Organizational Identification

However, some research has criticized the overly deterministic accounts of people’s engagement processes. Alvesson & Sandberg (2011) pointed out two tenets of OID research, which can serve to create problems. One is that “individuals and organizations are constituted by a set of inherent and more or less stable attributes.” The other is, “the attributes of the individual are comparable with the attributes of the organization through a member’s cognitive connection” (p. 261).

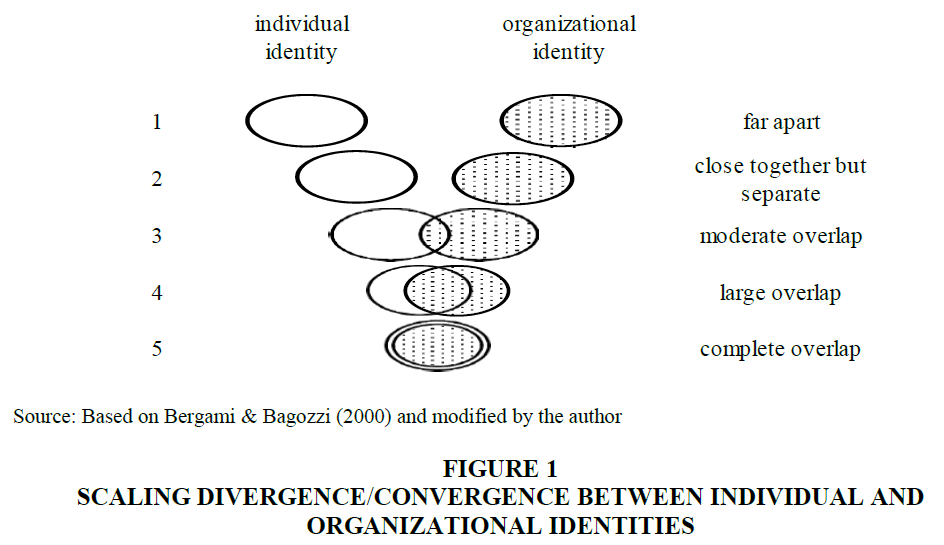

Bergami & Bagozzi (2000)’s OID scale is a good example by which to illuminate the problems with these tenets. They proposed a new scale of OID that measures the extent of an individual’s OID in order to quantify how individual identity on the one hand and OID on the other, manifest themselves differently in people. As such, they view OID as an objective entity. In other words, OID is out there. This understanding has led OID research to consider the individuals’ distances’ from OID. Moreover, previous OID research has framed the OID process in terms of how to reduce this distance so that individuals converge upon OID (Figure 1).

Here, the taken-for-granted assumption is that individuals are recipients of OID. In other words, they accord with the socially deterministic view of people’s engagement processes (Koerner, 2014).

Moreover, some authors have called for more attention to people’s engagement processes in the context of OID research. Ashforth (2001) noted that there is a dearth of research,” which aims to explore “how individuals struggle to create coherent and more or less stable definitions of themselves” (p. 10). Similarly, Kreiner, Hollensbe & Sheep (2006) pointed out a theoretical gap in terms of “understanding of the process of identity negotiation how identification waxes and wanes as individuals and their contexts evolve” (p. 1032).

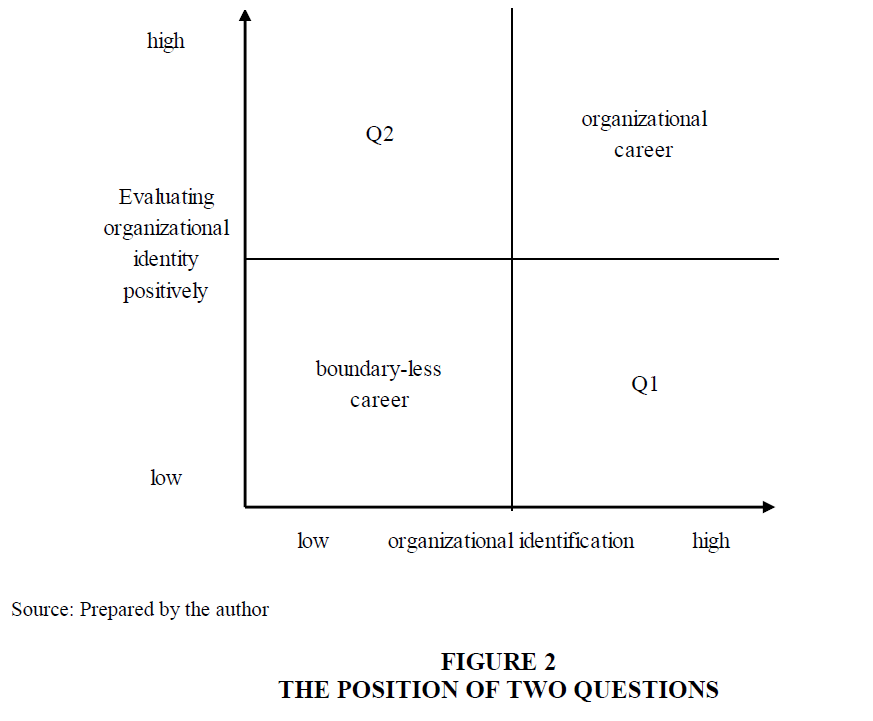

Therefore, this study concludes that conceptual and operational limitations in OID research mean that it is, at least currently, insufficient to explain the empirical observations in some contexts. Especially, I focus two situations which illustrate two questions with Figure 2. First question is why do some people who do not evaluate organizational identity positively, still identify that organizational identity exists (Q1)? Whereas second question is why do some people evaluate organizational identity positively, but dis-identify with organizational identity (Q2)? These people fall beyond the explanatory power of previous OID research and thus, we need a new framework, which captures the engagement processes of these people.

This study concludes that it is important to focus on these situations. Because we could get and deliver some knowledge of practices how to manage people’s own or their career. For individuals, to explore these situations means improving their engagement, whereas for organizations, it means finding out problems in and around the organization. Next, I will discuss the new framework; identity work.

Introducing Identity Work

The Essence of Identity Work

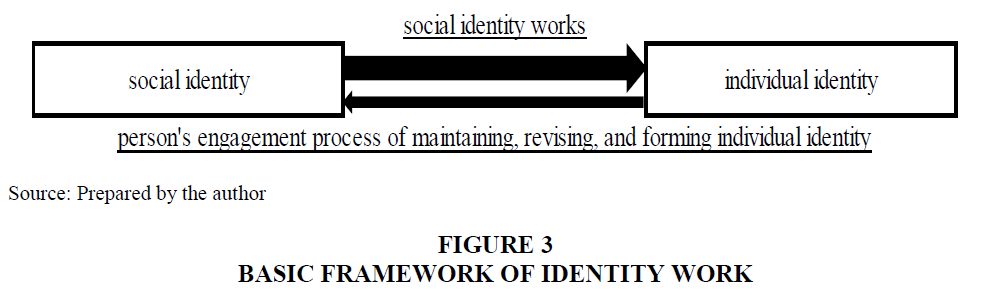

The theoretical basis of identity work is sociological research and critical theory. One of the popular definitions of identity work couches it in terms of “people being engaged in forming, repairing, maintaining, strengthening or revising the constructions that are productive of a sense of coherence and distinctiveness” (Sveningsson & Alvesson, 2003). Essentially, identity work is a framework for focusing on an individual’s engagement process in how to maintain, revise and newly form an individual identity in the situation of the social identity works of an individual.

It is important to note two points to understand this framework. First, the word “work” is not a noun but a verb. For example, in suspense a drama people usually say, “It seems to work by an invisible force.” Second, consequently, we identify per se what is being worked. Changing the words to “invisible force works on us” enhances the understanding (Figure 3).

In particular, this framework is useful when there is a large gap between working on social identity and individual identity. For example, there is a gap between the ideal occupational identity as a doctor and what medical residents actually do (Pratt, Rockmann & Kaufmann, 2006) or between the assimilation demanded of a priest which may conflict with the individual’s desire to maintain distinctiveness (Kreiner, Hollensbe & Sheep, 2006).

Elsbach (2009) investigates toy car designers who sense a gap between the demand for making ordinary toys and the desire to think, “I am creative.” In other words, she focused on the point when toy car designers’ identity works on them and how they engage to maintain, revise or form the individual identity of “I am creative.” She shows that toy car designers develop and express “signature styles” and these styles allow them to affirm their creative and professional identities while making ordinary toys. Here the signature styles are not advertised, stamped on products or even recognized in official corporate marketing communications; however, the designers know they exist.

Identity Work Overcomes the Problem of OID Conceptualization

Identity work research can overcome the socially deterministic view of people’s engagement processes. If social identity works on people’s individual identities, people’s responses or acts are not unilateral or unidirectional. For example, Kreiner et al. (2006) investigate how Episcopal priests conduct identity work to negotiate an optimal balance between personal and social identities. They examine identity demands, which denote the situational and vocational demands placed on those in challenging occupations. Social identity, as a calling, means that a vocation is a calling, not just a job or traditional occupation. Identity expectations, functional or ontological, denote what should be done or said or what his or her identity or image should be. A strong situation means specific contexts invoke or cue the identity demands. However, they also explore how Episcopal priests ameliorate these demands by several identity work tactics. They present three examples of these tactics. Differentiating tactics means that Episcopal priests consciously separate personal identity from social identity. Integration tactics means that they blend their personal identities with the occupation and/or organizational identity. Finally, neutral or dual-function tactics denotes that they could pursue either differentiating and integration tactics.

Thus, it can be concluded that identity work is a useful framework to enhance research into OID processes because it offers two mechanisms for overcoming problems with OID research. First, this framework converges on individuals’ engagement processes by showing when organizational identity works on them. Second, this framework allows individuals and organizations to have fluid and dynamic attributes rather than rigid and static alternatives, which lack empirical support.

Identity Work Research Problem

However, identity work research is not without problems. It is thus far unclear how to deal with complicated or multiple competing social identities, which create impediments to individuals pursuing identity work. Consequently, the previous research has tended to assume that every individual is able to do identity work when sensing such a gap. Indeed, Brown (2015) argues, “there is much we still do not know about how contexts affect individuals’ identities and identity work” (p. 31).

As noted above, OID research could not satisfactorily answer two questions. This study concludes that it is important to examine these two questions by using identity work. This is because in situations where these two questions are salient, individuals will find it difficult to do identity work. In other words, these two questions represent problems not only for OID and career research but also for identity work research. The next section suggests future research directions based on the foregoing arguments.

Discussion

This section suggests future research directions based on the two short cases. These cases show people’s engagement process that they proactively (re)create or maintain individual identity. Previous OID research have focused individuals in a somewhat reactive role or viewed them as socially deterministic, responding to negative or positive image of organizational identity. OID research, however, missed this engagement process. Thus, it is useful to introduce the new framework; identity work.

Tainted Identities

Why do some people who do not evaluate organizational identity positively, still identify that organizational identity exists (Q1)? One example here is that of a tainted organization or occupational identity. When tainted organizational or social identities operate on individuals, those individuals find it difficult to do identity work. According to Ashforth, Kreiner, Clark & Fugate (2007), individuals engaging in “dirty work”, which are regarded as physically, socially and/or morally tainted (Ashforth & Kreiner, 1999), tend to resist by working on stigmatized social identity.

However, Ashforth & Kreiner (1999) also pointed that individuals engaging in dirty work tend to retain relatively high occupational identification and Ashforth et al. (2007) examined the practices that they actively counter tainted identities or rendered them less salient. This study’s discussion is based on these researches and expands the situation of organizational corruption. Here, I pick up on the case of Petriglieri (2015).

Through a qualitative study of BP executives during and after the 2010 Gulf of Mexico oil rig explosion and spill, Petriglieri (2015) examined whether and how the relationship between an organization and its executives can be repaired once damaged. She posited three tactics: Strong re-identification; weak re-identification; and de-identification, from executives. Strong (weak) re-identification denotes strong (weak) reestablishment of identification with an organization following its destabilization. While de-identification means no reestablishment of identification occurs with an organization following its destabilization. All three of these processes are accompanied by relationship repair. Indeed, the most significant finding in this study was that credible relevant outsiders contributed to repairing the relationship between an organization and its members by providing not only positive, but also negative, information.

Reassessing Identities

Why do some people evaluate organizational identity positively, but dis-identify with organizational identity (Q2)? As noted above, identity work research has tended to focus on situations where large gaps exist between working on social identity and individual identity. The focus therein has particularly been on negative or disruptive events when studying identity dynamics in organizations.

In this respect, Petriglieri (2015) rationalizes that this “perhaps reflects the human tendency to attend to bad rather than good situations” (p. 548). On that basis, Petriglieri (2015) suggests that it is important to engage with identity reassessment in future research.

Investigating whether identity destabilization can also arise from events that appear beneficial, such as rapid organizational growth or unexpected success, would be a helpful extension in this area. Rapid growth, for example, might challenge an organization’s ability to retain its identity attributes because of an influx of new recruits, which could destabilize the identification of previous members. This problem has been suggested in anecdotes about fast-growing technology companies such as Google. (Petriglieri, 2015).

Moving on, Kjaergaard et al. (2011) research into Oticon becomes pertinent to consider here. Oticon is a hearing aid manufacturer based in Copenhagen, Denmark. Kjaergaard et al. (2011) examines how positive media representation effects on the reconstruction process of organizational identity and members’ engagement process.

In the beginning of reconstruction process, Lars Kolind, a charismatic manager of Oticon, made currently organizational policies and practices unclear and announced new policy; ‘Spaghetti Organization’. In here, ‘Spaghetti Organization’ means ‘project-based structure and organizational arrangement’ (p. 515). As a result, members perceived a discrepancy between new organizational identity and their organizational reality. However, media reported Oticon as celebrating the original and progressive nature of the firm. Positive image reported by media and the need to reconstruct the new organizational identity to match external positive image, brought members to gradually reduce a discrepancy. So, although members largely perceived media misrepresentations of their current organizational identity, the positive image of these misrepresentations induced members to identify Oticon’s organizational identity.

However, the positive image no longer corresponded to Spaghetti Organization. Over time, changes in internal policies and practices brought members’ daily experiences to become gradually detached from the ‘old’ policy of Spaghetti Organization. So, members seemed to perceive a new discrepancy between old organizational identity and their organizational reality. This discrepancy resulted in widely perceived ambiguity about Oticon’s organizational identity and members’ OID. However, to borrow Kjaergaard et al. (2011) words, ‘the members reported their increasing frustration at the reluctance of managers in choosing between a celebrated past identity that they were not inclined to implement any more and a yet-to-be-defined new identity that they were unwilling to articulate’ (p. 535). Kjaergaard et al. (2011) called this condition as ‘identity captivation’ which means that ‘they perceived as no longer being truthful, but which still ensured them considerable social recognition’ (p. 535).

Understanding when and why individuals find it difficult to do identity work is particularly meaningful in the context of studying modern contemporary careers. Where tainted organizational or social identities manifest themselves, we get and deliver knowledge on how we could be “proactive in shaping and crafting their identities to carve out a life worth living” (Kreiner & Sheep, 2009). Identity work tactics are examples of proactive work behaviors that lead to thriving at work. Thus, this is a highly proactive and intentional approach to positive identity development. (Kreiner & Sheep, 2009).

Whereas in organizational or social identity reassessment situations, we get and deliver knowledge on how complex organizational life could be in identity terms, particularly in the face of outsiders’ information or images. Future research on this topic could serve to develop an understanding of how outsiders’ information or image “may support or interfere with organizational leaders’ attempts to encourage change in organizational identity to support new organizational strategies” (Kjaergaard et al., 2011).

Conclusion

The purpose of this article was to review theoretically and critically extant OID research concomitant with introducing and positioning the concept of identity work in order to overcome problems with OID. In conclusion, this review puts forward three theoretical implications.

First, we unpack problems with OID research. As Miscenko & Day (2016) suggested, it is necessary to examine critically the assumption that OID is stable. This theoretical review shows that previous OID research has assumed that OID can be conceived as the distance between personal identity and organizational identity and the OID process refers to the ways in which individuals reduce or segregate between personal identity and organizational identity. Consequently, the previous research envisages that individuals can only change external factors, overlooking the possibility of individuals’ engagement processes.

Second, the notion of identity work is introduced and positioned as a useful framework to overcome the aforementioned problem with OID research. Moreover, we identify the advantages of identity work that can capture individuals’ engagement processes when organizational identity works on them, seeing individuals and organizations as having fluid and dynamic attributes.

Third, we discuss significance of the people’s career who were not well-know. This research generally supports the argument that “we are making about the need to take nuances, complexities and ambiguities seriously. The identity aspect here became quite complicated. (Alvesson & Robertson, 2016).

Finally, this theoretical review also provides practical implications. Through these discussions, we could call for an examination of what resources are deliverable by organizations for individuals’ identity work in a given context. It is important to understand the situations of individuals who are finding it difficult to manage their own career and for organizations who are struggling to provide appropriate support for individuals’ careers in dynamically uncertain environments.

References

- Albert, S. & Ashforth, B.E. & Dutton, J.E. (2000). Organizational identity and identification: Charting new waters and building new bridges. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 13-17.

- Alvesson, M. & Robertson, M. (2016). Organizational identity: A critique. In M.G. Pratt, M. Schulz, B.E. Ashforth & D. Ravasi (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Organizational Identity (pp. 160-180). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Alvesson, M. & Sandberg, J. (2011). Generating research questions through problematization. Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 247-271.

- Arthur, M.B. (1994). The boundary-less career: A new perspective for organizational inquiry. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15(4), 295-306.

- Ashforth, B.E. (2001). Role transitions in organizational life: An identity-based perspective. Mahwah NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Ashforth, B.E., Harrison, S.H. & Corley, K.G. (2008). Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. Journal of Management, 34(3), 325-374.

- Ashforth, B.E. & Kreiner, G.E. (1999). How can you do it?: Dirty work and the challenge of constructing a positive identity. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 413-434.

- Ashforth, B.E., Kreiner, G.E., Clark, M.A. & Fugate, M. (2007). Normalizing dirty work: Managerial tactics for countering occupational taint. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 149-174.

- Ashforth, B.E. & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20-39.

- Bergami, M. & Bagozzi, R.P. (2000). Self-categorization, affective commitment and group self-esteem as distinct aspects of social identity in the organization. British Journal of Social Psychology, 39(4), 555-557.

- Brown, A.D. (2015). Identities and identity work in organizations. International Journal of Management Reviews, 17(1), 20-40.

- Callea, A., Urbini, F. & Chirumbolo, A. (2016). The mediating role of organizational identification in the relationship between qualitative job insecurity, OCB and job performance. Journal of Management Development, 35(6), 735-746.

- Dukerich, J.M., Kramer, R. & Parks, J.M. (1998). The dark side of organizational identification. In D.A. Whetten & P.C. Godfrey (Eds.), Identity in Organizations: Building Theory through Conversations (pp. 245-256). Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Dutton, J.E., Dukerich, J.M. & Harquail, C.V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(2), 239-263.

- Edwards, M.R. & Peccei, R. (2010). Perceived organizational support, organizational identification and employee outcomes. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 9(1), 17-26.

- Elsbach, K.D. (2009). Identity affirmation through ?signature style?: A study of toy car designers. Human Relations, 62(7), 1041-1072.

- Hameed, I., Riaz, Z., Arain, G.A. & Farooq, O. (2016). How do internal and external CSR affect employees? organizational identification? A perspective from the group engagement model. Frontiers in Psychology, 7 (788).

- He, H., Pham, H.Q., Baruch, Y. & Zhu, W. (2014). Perceived organizational support and organizational identification: Joint moderating effects of employee exchange ideology and employee investment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(20), 2772-2795.

- Hogg, M.A. & Abrams, D. (1988). Social identifications: A social psychology of intergroup relations and group processes. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Khapova, S.N., Arthur, M.B., Wilderom, C.P. & Svensson, J.S. (2007). Professional identity as the key to career change intention. Career Development International, 12(7), 584-595.

- Kjærgaard, A., Morsing, M. & Ravasi, D. (2011). Mediating identity: A study of media influence on organizational identity construction in a celebrity firm. Journal of Management Studies, 48(3), 514-543.

- Koerner, M. (2014). Courage as identity work: Accounts of workplace courage. Academy of Management Journal, 57(1), 63-93.

- Kreiner, G.E., Hollensbe, E.C. & Sheep, M.L. (2006). Where is the ?me? among the ?we?? Identity work and the search for optimal balance. Academy of Management Journal, 49(5), 1031-1057.

- Kreiner, G.E. & Sheep, M. (2009). Growing pains and gains: Framing identity dynamics as opportunities for identity growth. In L.M. Roberts & J.E. Dutton (Eds.), Exploring Positive Identities and Organizations: Building a Theoretical and Research Foundation (pp. 23-46). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- LaPointe, K. (2010). Narrating career, positioning identity: Career identity as a narrative practice. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(1), 1-9.

- Miscenko, D. & Day, D.V. (2016). Identity and identification at work. Organizational Psychology Review, 6(3), 215-247.

- Petriglieri, J.L. (2015). Co-creating relationship repair: Pathways to reconstructing destabilized organizational identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 60(3), 518-557.

- Pratt, M.G. (1998). To be or not to be: Central questions in organizational identification. In D.A. Whetten & P.C. Godfrey (Eds.), Identity in Organizations: Building Theory through Conversations (pp. 171-207). Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Pratt, M.G., Rockmann, K.W. & Kaufmann, J.B. (2006). Constructing professional identity: The role of work and identity learning cycles in the customization of identity among medical residents. Academy of Management Journal, 49(2), 235-262.

- Riketta, M. & Van Dick, R. (2005). Foci of attachment in organizations: A meta-analytic comparison of the strength and correlates of workgroup versus organizational identification and commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(3), 490-510.

- Sveningsson, S. & Alvesson, M. (2003). Managing managerial identities: Organizational fragmentation, discourse and identity struggle. Human Relations, 56(10), 1163-1193.

- Tafjel, H. & Turner, J.C. (1986). Social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W.G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of Intergroup Relations (pp. 7-24). Chicago: Nelson-Hall.