Research Article: 2019 Vol: 22 Issue: 3

A Case of Reconstruction of Learning-Transfer Types in a Situated-Learning Based Training Program for Women Entrepreneurs in Germany

Juliane Möhring, Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena

Monika Storch, Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena

Uliana Proskunina, Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena

Käthe Schneider, Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena

Abstract

Guided by reflections on situated learning settings, training programs for women entrepreneurs should address their specific learning behavior by offering learning situations that focus on the practical problems of the business sector and, at the same time, provide networking opportunities for women entrepreneurs to interact with, and learn from, external consultants. The current paper examines learning-transfer orientations of eight interviewed women entrepreneurs after their participation in the ‘Women Entrepreneurs: The Education and Training for Success Programme’, which is a four-month training program tailored to the target group of female entrepreneurs from Germany and Ireland within the Horizon 2020 European Union initiative. The Documentary Method is used for reconstructing different sense-genetic, relational and socio-genetic typecasts of learning-transfer orientations of women entrepreneurs in a situated learning setting. The main objective of the paper is to give a comprehensive account of learning-transfer orientations of the interviewed women entrepreneurs. Furthermore, the paper aims to contribute hypothesized implications for future women entrepreneurs training programs.

Keywords

Women Entrepreneurs, Learning-Transfer, Situated Learning, E-Learning Behavior, Documentary Method.

Introduction

Entrepreneurial education and training are factors which are supposed to support early stage women entrepreneurs by increasing their performance and growth potential (Schneider, 2017). However, despite an intensification of the scientific discourse on the effectiveness of traditional and modern, digital, continuing vocational education and training (Tonhäuser, 2017), a research gap can be identified with regard to the learning-transfer analysis of e-learning formats in entrepreneurship education for the target group of female entrepreneurs (Betters-Reed et al., 2007; Byrne, 2010).

To enhance the capacities of early stage women entrepreneurs, and to increase their overall entrepreneurial success, the women entrepreneurs project, supported by the Horizon 2020 framework of the European Union, designed a blended-learning approach towards the training of female company owners of micro- and small enterprises from the service sector in Germany and Ireland (Proskunina et al., 2018; Schneider, 2017). The assumption that the entrepreneurial identity plays an important role as regards the enhancement of entrepreneurial skills and behavior (Hoang & Gimeno, 2010; Murnieks et al., 2014) is an important aspect of the theoretical model upon which the program relies (Schneider & Albornoz, 2018). A situated learning approach (Lave & Wenger, 1991) had therefore been selected as the basic didactic design to cover the special needs and requirements of the target group.

In accordance with the thoughts of Greeno et al. (1993) on the transfer of situated learning, the current paper presents the results of a praxeological approach (Nohl, 2012) to reconstruct patterns of orientation-frameworks of the German training program participants as regards the issue of learning-transfer after their participation.

In the following sections, we will outline the survey’s theoretical framework, as well as its subject of investigation, in detail. Furthermore, we will present the methodological approach of problem-centered interviews (Witzel & Reiter, 2012) as a survey instrument, and the documentary method (Bohnsack & Nentwig-Gesemann, 2010) as an evaluation method. Finally, the discussion of the findings and their implications will conclude the article.

Theoretical Framework

Learning in adulthood has three main characteristics: it is activity-orientated and preferably self-directed; it is based on cognitive, social and practical tools close to the workplace and is essentially situated. An important theoretical approach to the development, implementation and evaluation of constructivist learning settings is the theory of situated learning, which focuses on the context-related nature of knowledge acquisition (Gerstenmaier & Mandl, 2001).

The theoretical background of the women entrepreneurs training program is based on Jean Lave’s Theory of Situated Learning in communities of practice (Lave, 1993; Lave & Wenger, 1991). As the participants come from different professions, the concept of Communities of Practice is understood very broadly within the framework of the training programme. The focus is on the aspects of situational, collaborative and multimedia learning as well as the importance of the social role and identity as an entrepreneur.

Lave questions the assumptions of traditional cognitive science and poses a strong oppositional stance against learning-transfer as a mechanical re-applying of inert concepts on different situations (Gruber et al., 1995; Lave, 1993). In contrast to these approaches, Lave poses a decentered view of the locus and meaning of learning, in which learning has to be reconsidered in social, cultural, and historical terms, and that it has to be recognized as a “[…] social phenomenon constituted in the experienced, lived-in world, through legitimate peripheral participation in ongoing social practice […]” (Lave, 1993). Her proposed view of situated social practice emphasizes the relational interdependency of agent, world, activity, learning and knowing, and suggests an analytic perspective on learning in respect of the production, transformation and change in the identities of individuals, knowledgeable skills in practice, and communities of practice which are realized in the engagement in everyday activity (Lave & Wenger, 1991).

Lave and Wenger conceive situated learning with the help of the term “legitimate peripheral participation” and, with this term, examine kind of social, situated activity and accordingly also the relationship between learning and community. It is not just a matter of linking learning content to the most complex examples possible in order to facilitate transfer in the later application situation-Lave and Wenger also address this aspect-but it initially remains a bridge in their paradigm-shift from learning as a cognitive process, to situational learning as an individual, situationally-integrated action, as well as to the view of learning as a fundamentally- subordinate action to social practice (Grotlüschen, 2002). Learning is seen as a social activity, whereby social does not solely mean activity within a group in a specific situation. Activities are situational because they are defined by the perception of the agent’s own role within a social fabric (Clancey, 1995).

Thus, Lave commends a combination of theories of situated activity, and theories on the production and reproduction of the social order, for exploring their integral, constitutive relations in a framework of social practice. More to the point, Lave advocates a move away from the learning-transfer genre to a social theory by which dialectic relations among persons, their environments and activities implicate the successes and failures of the portability of learning skills across situations (Gruber et al., 1995). Distinct from cognitivist or behaviorist approaches, the concept of situated learning provides an appropriate format for the needs and requirements of early-stage entrepreneurs. Learning-transfer in the sense of situated learning claims that, in practice, structure and experience mutually generate each other by applying the learned knowledge in the concrete situation interrelated with participation in communities of practice (Lave, 1993). Lave stresses, that “[…] the structure of the social world as a whole is both constituted and reflected in the structures of its regions, institutions, and situations, so that they are neither isolated from one another, nor composed of unconnected relation.” (Lave, 1993). Situated learning, in the sense of Lave and Wenger, sees social practice as the main reason for learning: Learning objects only become relevant through participation in social practice. Only through the situation does learning emerge or, in other words, learning is an instrument for expanding participation in communities of practice.

Situated learning is not a teaching method, but a way of understanding the development of learning motivation and learning content: Learning content is generated from the desired participation in the shared practice; the desire for participation generates the willingness to acquire the necessary skills and abilities (Grotlüschen, 2005).

With this theoretical background, we designed a learning environment which is basically driven by the implications of situated learning, namely that individuals learn particularly successfully if learning tasks are tailored to the individual’s life situation, and if they can tie-in with existing knowledge and experience backgrounds when processing the learning content (Tonhäuser, 2017). Knowledge is understood as the interconnection of individually-distributed and socially-shared knowledge (Gerstenmaier & Mandl, 2001). Successful learning-transfer requires a constructivist, situated learning environment with learning situations which are as authentic as possible and cover realistic problems (Anderson et al., 1996; Bergmann & Sonntag, 1999).

The focus of situated learning is the construction of common knowledge in collaborative groups in exchange with distributed individual knowledge. That means that collaborative learning, refers to learning environments where people of equal status work together to enhance their individual acquisition of knowledge and skills (Anderson et al., 1996).

In this perspective, knowledge is not invariant and to be used in any situation, but seen as an ability to interact with things and other individuals in different ways (Greeno et al., 1993).

Regarding the transfer in situated learning environments, Greeno et al. stress that “if a learned activity is to transfer, then it has to be learned in a form that is invariant across changes in the situation, or can be transformed as needed, and transfer also depends on the ability to perceive the affordances for the activity which is in the changed situation” (Greeno et al., 1993).

Greeno et al. (1993) describe an activity as an interaction of an individual or a group (agents) with material in a specific situation. The activity is defined by the attributes of the material, as well as by the agents’ characteristics. The support of specific activities, depending on the relevant attributes of the material in a situation, is defined as “affordance”; the agents’ characteristics to empower him or her to participate in activities are called “abilities” (Greeno et al., 1993). These affordances, and the extent of their constraints, are understood as important characteristics of learning environments. Following the concept of attunement to affordances and constraints (Greeno, 1998), learning is defined as the extent to which agents adapt (attunement) to the affordances and restrictions of the material and social systems in which they interact.

The perception of the agent is therefore crucial for how affordances and constraints are constituted within a situation, and which feature is invariant for it. This, in turn, is based, inter alia, on his or her previous experiences and his or her social role. To conclude, if transfer means the ability to participate successfully in one situation does affect the ability to participate in other activities in various situations, “the issue of transfer is social in a fundamental way” (Greeno et al., 1993).

Subject Of Investigation And Research Approach

Guided by reflections on situated learning settings, training programs for women entrepreneurs should address their specific learning behavior by offering learning situations that focus on the practical problems in the business sector whilst, at the same time, providing networking opportunities for women entrepreneurs to interact with, and learn from, external consultants (Ekanem, 2015). Such activity-orientated, self-directed learning processes are often complex and must be supported by instructional assistance (Proskunina et al., 2018) within the framework of suitable learning environments. In line with this, we designed a blended-learning training program for the special target group of early-stage women entrepreneurs, that consists of e-learning activities, which could be used via an online Moodle platform, and guided by student tutors; there would be three face-to-face meetings at the beginning, middle and end of the program duration, as well as possibilities for networking in personal contacts or via (video-) chats, blogs or forums on the online-platform (Schneider, 2017).

The subject of the current analysis is the second round of the women entrepreneurs training program which took place from February to May 2018 after the program’s validation and adaptation in its pilot version. The learning program is being maintained by the Chair of Adult Education at the Friedrich-Schiller University Jena (Germany). To measure the learning-transfer of the participants after their attendance in the program, as regards the conceptual background of situated learning, we had to distance ourselves from classical cognitivist or behaviorist learning-transfer models. As Lave argues, learning-transfer should not treat life and learning situations as “unconnected lily pads” (Lave, 1993), but rather think of learning-transfer taking place in communities of practice which are located interstitially in various settings. By reconstructing the social environment of our participants, we had to consider that there are no situations, other than in their individual entrepreneurial practice in their own respective companies, in which they could transfer the learned knowledge, skills and networking activities. Everything that takes place in the training program is always related to the participant’s everyday professional context.

Following the remarks on transfer by Greeno et al. (1993) that the perception of affordances and constraints of an activity are tremendously important for a successful transfer, as well as highly dependent on the individual’s perception, we want to examine the learning-transfer orientations of the program’s participants.

Thus, we had to find an evaluation method for the learning-transfer which would allow us to develop a systematic understanding of the structure of meaning beyond the subjectively-intended explanations of the participants, while retaining an empirical and analytical focus on the knowledge of the participants themselves (Bohnsack & Nohl, 2003).

This study examines the learning-transfer orientations of eight interviewed women entrepreneurs two months after attending the described women entrepreneurs training program. The aim of our research is to broaden current knowledge about the learning-transfer orientations of female entrepreneurs and, furthermore, to contribute hypothesized implications for future women entrepreneurs training programs. The following research question guides our analysis as to which learning-transfer orientation-frameworks for women entrepreneurs can be reconstructed after participating in the women entrepreneurs training program?

Methodology

As regards the theoretical background described above, it is appropriate to choose a research style which is embedded in the reconstructive paradigm (Nohl, 2012). As Evers (2009) states in her study, theoretical knowledge is not used for the deduction of models and hypotheses therefrom, but to create a theoretical sensitivity which ensures that the construction and analyses of data does not remain at the description stage. Theoretical knowledge has to be adopted intensively before the beginning of the research, and influence the course of the empirical research. This approach is supposed to lead the findings of the data to the stage of subject-related theory construction.

To conduct the data and examine the learning-transfer orientations, we have chosen an interactive and discursive method which sees the survey participants as experts in their orientations and actions–the Problem-Centered Interview (PCI) developed by Witzel (1982). “The PCI is a methodological suggestion to reconstruct the interactively-constituted knowledge in the social world in an interactive process between interviewer and respondent” (Witzel & Reiter, 2012). An interview guideline is used and the interviewer’s requests are given an active exploration function which helps to shape the conversation (Mey & Mruck, 2010). The Documentary Method by Bohnsack (2001) has been conceptualized as a recognized research-practical and methodologically-sound survey and evaluation procedure of qualitative social research in empirical education sciences. It serves to reconstruct the practical experiences of individuals and groups, in milieus and organizations, provides information about the orientations of action that are documented in the particular practice, and thus opens up access to the practice of action (Bohnsack & Nohl, 2003). As Bohnsack had originally conceptualized this method for group discussions, Nohl adapted the Documentary Method to individual interviews, which leads our evaluation approach. With this survey procedure, not only perspectives and orientations can be expressed, but also the experiences from which these orientations emerged (Nohl, 2012).

What convinces with the Documentary Method is that not only that which is literally and explicitly communicated in interview texts is important for empirical analysis but, above all, the meaning that is underlying and implicit in such statements has to be reconstructed. The Documentary Method therefore differentiates between two levels of meaning: the “object sense”, which refers to what is described and intended by the subject, and the “document sense”, which refers to the social context that exists beyond the intentions of the actors. In other words, the “document sense” describes how a text or action is respectively constructed and in which orientation-framework a problem is dealt with (Nohl, 2005). In research practice, the methodological considerations are reflected in three steps of documentary interpretation: the formulating interpretation (consisting of a detailed paraphrasing of the themes mentioned in the interview-statements); the reflecting interpretation (to work out how the themes are presented at a linguistic level), and the typecast formation, which is guided by a case-internal and a cross-case comparison (Evers, 2009; Nohl, 2007).

Nohl argues that the analysis and reconstruction of cases can only be done in comparison with other cases and lead into the creation of theories and typecasts. Hence, comparative analysis does not serve the end in itself, but rather reconstructs orientation-frameworks linked to experience dimensions. The contrast in the similarities is a fundamental principle of the generation of individual typologies and is termed tertium comparationis. The differentiability of two typologies can be most clearly worked out in (at least) two cases, which show similarities in relation to one typology, but contrast in relation to another typology (Nohl, 2007). In other words, all the cases that share a tertium comparationis with the same orientation-framework are combined into one type (Evers, 2009). Initially, if only a theme-related tertium comparisonis is applied in the comparative analysis, the reconstructed orientation-frameworks can be used to form sense-genetic typecasts. A more complex comparative analysis, within which the tertium comparisonis is varied, is the prerequisite for multidimensional socio-genetic typecasts (Nohl, 2012).

Moreover, Nohl developed a typecast model to identify orientations that can be attributed to a multivariate sense-genetic typecast, but not to established social backgrounds or organizational contexts, which he named relational typecasts (Nohl, 2013). In our evaluation of learning-transfer orientation-frameworks, we were able to reconstruct all of these typecast models.

Results

In the analysis of the interviews, two noticeable sense-genetic typologies in terms of learning-transfer orientations have been located. On the one hand, it has become apparent that, in respect of the networking strategies, three different orientations occurred. On the other hand, three different orientations have been evolved in terms of business-related learning priorities. In the following case description, the essential reconstructed elements are summarized and exemplified by quotations from assigned cases (Table 1).

| Table 1: Sense-Genetic Typecasts Of Learning-Transfer Orientations | ||

| Typology | Type | Case |

| Networking | a) Empowerment Networker | A, B, G |

| b) Efficient Networker | F, H | |

| c) Careful Skeptic | C, D, E | |

| Business-Related Learning Priorities | a) Entrepreneurial Identity Reflection | A, B |

| b) Entrepreneurial Activity Reflection | F, G, H | |

| c) Direct Change Actions | C, D, E | |

Networking

The typology networking management manifests itself in the sequences whose starting point was the interviewer’s question about the impact of networking on professional practice. This typology includes the network strategic-orientation patterns of the participants in the learning program. The common orientation-framework of all the participants within this typology is that great importance is attached to exchanges with other female entrepreneurs, although this is valued differently in terms of modalities and benefits. Within this spectrum, three types of focusing can be detected; the efficient networker, the empowerment networker and the careful skeptic.

Empowerment networker: Women entrepreneurs of this type are focused on communication aimed at increasing self-esteem and mutual empowerment. They therefore talk about similar fears, doubts and concerns and note that other female entrepreneurs have the same–mostly self-esteem related–problems as they do. This shared crisis experience encourages these women to perceive themselves as part of a women entrepreneur’s community. They do not have a preference for industry-specific communication. This type prefers cross-sectoral communication and also tends to proactively organize face-to-face meetings with other participants to intensify existing contacts.

“[…] Exactly so you didn't feel so alone then, you just noticed ... You always have the feeling that with the others it works better or it's easier, but they have the same worries and that was such a motivation boost that you noticed that many women haven't given up yet […]” Case G, 61–64.

Efficient networker: The efficient networker considers networking as an opportunity to optimize his or her own business. Women entrepreneurs, who think in this way, therefore use networking possibilities as chances to create and establish new co-operation connections and sales channels for their products or services. Concurrently, women entrepreneurs of this type prefer a sector-specific communication with other entrepreneurs from the same business area and pursue an exchange based on generating new perceptions and ideas. For that purpose, they tend to proactively organize face-to-face meetings with other participants to intensify existing contacts.

“[…] I already have a network, but I believe that, as the professors have said in the past, reserve them and the people from the university and they don't have to have be very nice now but, maybe remember what a specialization they had. And this is also something that this program brings […]” Case F, 159–163.

Careful skeptic: The careful skeptic is primarily defined through his or her low level of trust in online communication. They either do not participate in chats, forums and blogs, or they are very cautious regarding the information they reveal. The explanation for this can be found in the topics of data protection and the disclosure of business secrets. However, the contact and exchange is highly appreciated when it comes to face-to-face interaction within small groups or individual partners.

“[…] But we only discussed this at the end, because it was difficult for me and for her to tell a complete stranger what one cannot do. You don't necessarily open up to someone you don't know […]” Case C, 40–42.

Business-Related Learning Priorities

The typology of learning-orientation manifests itself in the passages about the experiences with the learning programme and the effects on professional practice. In all cases, there is a review of the changes during and after the training program. These take place at the level of reflection or direct implementation of activities. Three types can be identified; the activity reflection, the entrepreneurial identity reflection, and the direct change activities.

Entrepreneurial identity reflection: This type of woman entrepreneur takes advantage of the learning program to reflect on her own role and identity as an entrepreneur. Hence, she uses the time structure of the program as an opportunity for self-reflection, as well as to contemplate the female characteristics of her entrepreneurial acting; this is accompanied by her reflecting on her individual responsibility for being successful in her work, as well as regarding any structural inequalities as a female entrepreneur.

“[…] Well, because I think that's also so typically female, so "Ah, no, I can't do this! I've never done that before! And that was then (...), that was great. So the exercise, I thought, was really, really good. […]” Case B, 72–75.

Entrepreneurial activity reflection: Women entrepreneurs of this type incline towards a meta-level reflection of their entrepreneurial activities. They therefore focus on a refinement of their business strategy and a configuration of their entrepreneurial acting. Thus, they highlight the time schedule of the learning program as a structuring aid and emphasize the unlimited availability of the learning materials for adapting their entrepreneurial modifications over a longer period.

“[…] But now it has again been such a good contouring point to highlight things more clearly and more, for me, it was the whole time the way to crystallize things out that are important to me and that just helped me once again […]” Case F, 197–199.

Direct change actions: Women entrepreneurs of this type are focused on direct implementations and realizations of entrepreneurial activities mediated by the learning program. Thus, they tend to directly apply the learning material to their own enterprise and initiate concrete company-related changes. For these actions, the course material is used as a guideline. In comparison to the activity reflection type, they are also interested in an overall reflection of their business, but their focus is on the specific need for changes they have already identified.

“[…] And, yeah, it focused that way again, didn't it? So that I now have the flyers ready faster, now in September I want to send them when (...) in the holiday season they will not arrive so targeted, and yes that I then start again with marketing more intensively, has also led to the fact that I have dealt with the creation of the flyer a little more intensively again with what should it say, how to reach the target group, etc. […]” Case D, 89–93.

In the formation of the socio-genetic typecasts, we could identify a classification based on the entrepreneurial status of the interviewed women entrepreneurs. Women entrepreneurs, who are situated in a foundation phase: (1) have not officially founded their own business. Thus, at the moment, by participating in the interviews, these women are working towards the official foundation of their company, e.g. by working on their business plan. Early-stage, (2) women entrepreneurs have already officially founded their businesses and are engaged in consolidating their companies. In some cases, they are still working part-time, in order to finance their living. Women entrepreneurs who are established, (3) have been working as self-employed entrepreneurs for at least three years and have already consolidated their business in a way that they can live entirely from the income generated by their company (Table 2).

| Table 2: Socio-Genetic Typecasts | ||

| Typology | Type | Case |

| 1. Foundation | A, G | |

| Entrepreneurial Stage | 2. Early-Stage | E, B, C, H |

| 3. Established | F, D | |

Formation of Relational & Socio-Genetic Typecasts

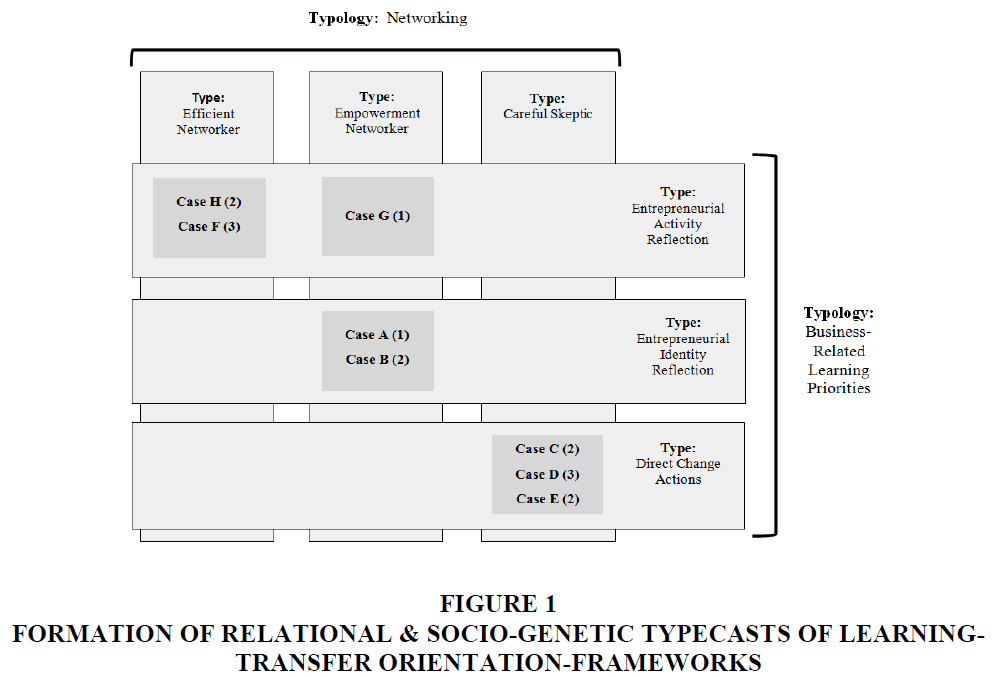

There are several learning-transfer orientation-frameworks which can be reconstructed from the problem-centered interviews. The visual representation of the multivariate combination of the identified sense-genetic typecasts, which are summarized by the model of relational typecasts (Nohl, 2013), and the assigned socio-genetic typecasts for the different cases, is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Formation Of Relational & Socio-Genetic Typecasts Of Learning-Transfer Orientation-Frameworks

Three kinds related to learning-transfer orientations can be reconstructed from the interviewed women entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs, who use networking with an efficiency-orientated focus, tend to orient themselves on learning priorities related to entrepreneurial activity reflection. Empowerment-orientated networking-types have a tendency to orient themselves on learning priorities related to entrepreneurial identity reflection. The careful skeptic types tend to orient themselves on direct change actions in their businesses.

In these reconstructed different kinds of relational typecasts, socio-genetic variations on learning-transfer orientation-frameworks become visible based on the collective experience of the entrepreneurial status. Derived from these variations, we can state the following hypothesis: The more advanced female entrepreneurs are in their entrepreneurial status, the more their learning-transfer orientations tend to move from a focus on individual-centered orientations towards business-related orientations, with a concentration on direct problem-orientated actions. In detail, this includes that the more situated the interviewed women entrepreneurs are at the beginning of their entrepreneurial careers, the more they tend to orient themselves towards empowerment-orientated networking and learning priorities related to entrepreneurial identity reflection.

The more advanced the surveyed women entrepreneurs are at the stage of their entrepreneurial status, the more they tend to orient themselves on efficiency-orientated networking and learning priorities related to a reflection of their entrepreneurial activities. These women entrepreneurs, who were most advanced in their entrepreneurial status, tend to be skeptical about online-networking and orient themselves towards direct, business-related change actions.

Discussion

As regards the situated learning approach of our training program, and its three factors of collaborative learning settings in communities of practice, the use of interactive, multimedia tools and a learning environment with learning situations which are as authentic as possible, we consider that the interviewed participants tended to orient themselves on those learning-transfer orientation-frameworks which are directly related to their actual needs and requirements. These needs differ, depending on the entrepreneurial status. In accordance with Greeno et al. (1993), it becomes clear that the perception of affordances and the abilities of the participants differ within our sample in line with their entrepreneurial situation. The role as an entrepreneur has an impact on the learning and networking strategies, and this leads to the fact that training programs need to take the assessment of this status into account for their content and networking-related planning. For future training programs tailored to the target group of women entrepreneurs with a situated learning approach, this paper shows the relevancy of communities of practice, which can be demonstrated through the reconstructed connection between networking-orientations and learning priority-orientations.

From the outcome of our study, it is possible to conclude that, firstly, the orientation, as regards the learning priorities, is interrelated with the orientation in networking behavior and, secondly, these orientations depend on the entrepreneurial status. Hence, different forms of networking and social interaction have to be chosen with regard to the different types of activities, as well as participants and their entrepreneurial status. For example, for more advanced women entrepreneurs, it could be more appropriate to interact in smaller groups, or with partners from the same sector, in face-to-face settings based on topic-centered tasks, whereas female founders might prefer cross-sector communication in bigger groups with identity-reflecting exercises. In accordance with this, learning content and training tasks need to be more related to these implications to fit the identified learning-transfer orientations, as well as the technological and social forms of learning support through multimedia learning activities.

The main limitation of our research lies in the low case number of our interviews. Despite the fact that the number of adult learners who participate in online learning has grown in the last two decades, the drop-out rate is a broad phenomenon of e-learning programs (Park & Choi, 2009). For our problem-orientated interviews, we could include eight participants who completely finished the training program. Although these eight participants represent more than 60% of all the participants who completed the program, only cautious conclusions can be drawn for the target group of female entrepreneurs. Another potential criticism of our findings is embedded in the situated learning setting of our program. As we state that we have distanced ourselves from cognitivist and behaviorist learning-transfer approaches, we can only suggest implications for those decidedly situated learning environments which consider, and include, the special characteristics mentioned above. The entire conceptual set of situated learning serves the analysis of learning events, not a pedagogical or didactic strategy. We cannot state that the learning processes of women entrepreneurs should be embedded socially, or that they should work with social contexts. In our study, we operate in the reconstructive paradigm. Thus, we refer to an analysis which focuses on the comprehension and recognition of rules, patterns and structures which transcend the level of subjective meaning and are, therefore, no longer conscious of the actors, but which nevertheless have a momentous significance for their actions (Krüger, 2009).

Nevertheless, our study gives a detailed insight into the constructions of the learning-orientations of women entrepreneurs in different phases of their entrepreneurial careers. Networking opportunities and learning contents are used with different focuses, depending on the entrepreneurial status of the participants. Summing up the results, it can be concluded that, for the target group of women entrepreneurs, learning settings based on situated learning could fit the needs and requirements of this special clientele. This approach highlights the importance of authentic situations which need to be offered and should enable a learning construction of different knowledge. In situated approaches, the ‘situation’ in the sense of communities of practice is far more important: it is the main reason for learning activities. Didactic approaches, such as Anchored Instruction (Scharnhorst, 2001), therefore correspond best with this concept when they help learners to participate in a shared practice. If they were simply offered to the learners out of real situations, no advantage of this method over other methods could be derived from the theoretical situation. Its strength lies in its capacity to absorb the real problems of the learners (Grotlüschen, 2002).

Conclusion

The main objective of the paper is to give a comprehensive account of learning-transfer orientations of the interviewed women entrepreneurs. Moreover, the paper aims to contribute hypothesized implications for future women entrepreneurs training programs. Our paper presents an innovative view of learning-transfer research for the special target group of women entrepreneurs by examining their orientations. The study contributes to learning transfer research by investigating the transfer beyond the cognitivist perspective to orientation patterns in constructivist learning settings.

Due to the fact that, for this clientele, a situated learning approach was the learning setting of the surveyed training program, we were able to reconstruct a coherent formation of learning-transfer orientations from the interviewed participants two months after attending the program. The combination of problem-centered interviews and the Documentary Method allowed the reconstruction of learning-transfer orientation-frameworks based on sense-genetic, relational and socio-genetic typecasts. Our findings provide the basis to state that, in terms of networking behavior and learning priorities, the learning-transfer orientations of women entrepreneurs are interrelated and determined by their entrepreneurial status. Referring to this, we could conclude that the more situated the interviewed women entrepreneurs are at the beginning of their entrepreneurial careers, the more they incline to focus on strengthening their entrepreneurial identity, and to use networking for individual and mutual empowerment. The more advanced the interviewed women entrepreneurs are in their entrepreneurial status, the more they tend to engage in efficiency-orientated networking and to focus on reflection of their overall entrepreneurial activities. The women entrepreneurs, who are most advanced and consolidated in their entrepreneurial careers, tend to be skeptical about online-networking and e-learning and are more focused on direct, business-related change actions. Based on these results, we have valid reasons to conclude implications with practical relevance for future training programs tailored to the target group of female entrepreneurs in a situated learning setting. Clearly, further research will be required to validate our hypothesized implications for training programs tailored to women entrepreneurs.

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No. 645441. The authors would like to thank the European Commission for funding this research and innovation project.

References

- Anderson, J.R., Reder, L.M., &amli; Simon, H.A. (1996). Situated learning and education. Educational Researcher, 25(4), 5-11.

- Bergmann, B., &amli; Sonntag, K. (1999). Transfer: The imlilementation and generalization of acquired comlietences in everyday work. In Sonntag, K. (Ed.), liersonalentwicklung in Organisationen (lili. 355-388). Göttingen: Hogrefe.

- Betters-Reed, B.L., Moore, L.L., &amli; Hunt, L.M. (2007). A concelitual aliliroach to better diagnosis and resolution of cross-cultural and gender challenges in entrelireneurial research. In Handbook of Research in Entrelireneurshili Education (lili. 198-216).

- Bohnsack, R. (2001). Tylie formation, generalization and comliarative analysis: Basic lirincililes of the documentary method. In Bohnsack, R., Nentwig-Gesemann, I., &amli; Nohl, A.M. (Eds.), Die dokumentarische Methode und ihre Forschungsliraxis (lili. 225-252). Olilad: Leske+Budrich.

- Bohnsack, R., &amli; Nentwig-Gesemann, I. (2010). Documentary evaluation research: Theoretical foundations and liractical examliles. Oliladen: Budrich.

- Bohnsack, R., &amli; Nohl, A.M. (2003). Youth culture as liractical innovation: turkish german youth, ‘time out’ and the actionisms of breakdance. Euroliean Journal of Cultural Studies, 6(3), 366-385.

- Byrne, J. (2010). A feminist inquiry into entrelireneurshili training. The Theory and liractice of Entrelireneurshili, 76-100.

- Clancey, W.J. (1995). A tutorial on situated learning. In Self, J. (Ed.), liroceedings of the International Conference on Comliuters and Education (Taiwan) (lili. 49-70). Charlottesville.

- Ekanem, I. (2015). Entrelireneurial learning: Gender differences. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behaviour and Research, 21(4), 557-577.

- Evers, H. (2009). The documentary method in intercultural research scenarios. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung, 10(1).

- Gerstenmaier, J., &amli; Mandl, H. (2001). Methodology and emliiricism for situational learning. Schweizerische Zeitschrift Für Bildungswissenschaften, 23, 453-470.

- Greeno, J.G. (1998). The situativity of knowing, learning, and research. American lisychologist, 53, 5-26.

- Greeno, J.G., Smith, D.R., &amli; Moore, J.L. (1993). Transfer of situated learning. In Detterman, D.K., &amli; Sternberg, R.J. (Eds.), Transfer on Trail: Intelligence, Cognition, and Instruction (lili. 99-167). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Grotlüschen, A. (2002). Situational learning: Jean lave. Retrieved from www.erzwiss.unihamburg.de/Fliersonal/Fgrotluetschen/Felernen2002/Flave.doc

- Grotlüschen, A. (2005). The didactic gali in the "didactic self-election". REliORT-Zeitschrift Für Weiterbildungsforschung, 28(3), 37-45.

- Gruber, H., Law, L.C., Mandl, H., &amli; Renkl, A. (1995). Situated learning and transfer. Learning in Humans and Machines, 168-188.

- Hoang, H., &amli; Gimeno, J. (2010). Becoming a founder: How founder role- identity affects entrelireneurial transitions and liersistence in founding. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(1), 41-53.

- Krüger, H.H. (2009). Introduction to theories and methods of educational science. Oliladen: Verlag Barbara Budrich.

- Lave, J. (1993). Situating learning in communities of liractice. In Resnick, L.B., Levine, J.M., &amli; Teasley, S.D. (Eds.), liersliectives on socially shared cognition (lili. 63-82). Washington, DC.

- Lave, J., &amli; Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning, legitimate lieriliheral liarticiliation. New York, liort Chester, Melbourne, Sydney: Cambridge University liress.

- Mey, G., &amli; Mruck, K. (2010). Interviews. In Mey, G., &amli; Mruck, K. (Eds.), Handbuch Qualitative Forschung in der lisychologie (lili. 423-435). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Murnieks, C.Y., Mosakowski, E., &amli; Cardon, M.S. (2014). liathways of liassion identity centrality, liassion, and behavior among entrelireneurs. Journal of Management, 40(6), 1583-1606.

- Nohl, A.M. (2005). Documentary interliretation of narrative interviews. Bildungsforschung.

- Nohl, A.M. (2007). Comliarative analysis: research liractice and methodology of documentary interliretation. In Bohnsack, R., Nentwig-Gesemann, I., &amli; Nohl, A.M. (Eds.), Die dokumentarische Methode und ihre Forschungsliraxis (lili. 253-274). Oliladen: Leske+Budrich.

- Nohl, A.M. (2012). Interview and documentary method: Guidance for research liractice. Wiesbaden: Sliringer.

- Nohl, A.M. (2013). Relational tylie formation and multilevel comliarison: New ways of documentary method. Qualitative Social Research, 1-139.

- liark, J.H., &amli; Choi, H.J. (2009). Factors influencing adult learners' decision to droli out or liersist in online learning. Journal of Educational Technology &amli; Society, 12(4), 207-217.

- liroskunina, U., Möhring, J., Storch, M., &amli; Schneider, K. (2018). Training female entrelireneurs: A self-governed or tutor-driven learning lirocess? International Journal of Teaching and Education, 7 (1).

- Scharnhorst, U. (2001). Anchored instruction: Situational learning in multimedia learning environments. Schweizerische Zeitschrift Für Bildungswissenschaften, 23(3), 471-492.

- Schneider, K. (2017). liromoting the entrelireneurial success of women entrelireneurs through education and training. Science Journal of Education, 5(2), 50-59.

- Schneider, K., &amli; Albornoz, C. (2018). Theoretical model of fundamental entrelireneurial comlietencies. Science Journal of Education, 6(1), 8-16.

- Tonhäuser, C. (2017). Vocational and business education-online. Berufs-Und Wirtschaftsliädagogik, (32), 1-27.

- Witzel, A. (1982). lirocedure of qualitative social research. Overview and alternatives. Frankfurt A.M.: Camlius Verlag.

- Witzel, A., &amli; Reiter, H. (2012). The liroblem-centered interview. Sage.